FORMA BREVE N13 CAPA#01.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mtv's News & Documentaries Department Presents True

MTV’S NEWS & DOCUMENTARIES DEPARTMENT PRESENTS TRUE LIFE: I’m in an Interfaith Relationship Relationships can be tough but, what happens when the person you love doesn’t share the same faith as you do? Can the differences ever be put aside? With over 4,000 known religions in the world, from traditional faith to new age beliefs, interfaith relationships are very common. For some people faith and religion is instilled from a very early age and usually lasts a lifetime. For others, faith is found later in life. Either way, there is not much that will make these individuals change or compromise their religion and faith…not even meeting the love of their life. Are you currently dating someone who doesn’t share the same religious background as you? Do your family and friends not understand? If you appear between the ages of 18-28 and you want to share the challenges and benefits of being in an interfaith relationship, we want to hear from you. Please email your contact info, recent pictures of you and your loved one, and explanation of your current relationship to [email protected]. True Life wants to experience your interfaith relationship from your point of view. Since 1998, True Life, an Emmy Award winning documentary series, has covered a diverse mix of stories, ranging from pop culture trends to breaking news topics. Whether documenting the lives of soldiers going to war, or people undergoing plastic surgery -- True Life tells its stories solely from the varied voices and points-of-view of its characters -- putting the series in the unique position of reflecting the state of youth culture at any given moment. -

Bad Cats : a Collection of Feline Pranks and Practical Jokes

BAD CATS : A COLLECTION OF FELINE PRANKS AND PRACTICAL JOKES Author: Rick Stromoski Number of Pages: 112 pages Published Date: 01 Apr 1995 Publisher: McGraw-Hill Education - Europe Publication Country: London, United States Language: English, Multiple languages ISBN: 9780809234783 DOWNLOAD: BAD CATS : A COLLECTION OF FELINE PRANKS AND PRACTICAL JOKES Bad Cats : A Collection of Feline Pranks and Practical Jokes PDF Book I was amazed that in just eight short months, he dramatically lowered the number and severity of workers' compensation claims we typically had through the years, improving our profitability and lowering your operating costs. Ray â Jana P. It includes technology standards specific to educational administrators, a survey testing a school's TQ (Technology Quotient, or its readiness to embrace both the digital principle and the digital principal), tips for grant writing to improve a school's resources, and ways to support teachers in becoming facilitators to students' learning with technology. The oldest subway routes received much needed rehabilitation. Cooke's abuse was calculated and terrifying. Energy measurement using an ultracapacitor is also presented. Six chapters organized by wall types, from hand-set monolithic walls to digitally fabricated curtain walls, each have a material focus section to help you understand their intrinsic properties so that you can decide which will best keep the weather out of your building. Reducing Error and Influencing BehaviourA charming, off-the-wall and thoroughly entertaining travel book recounting the true-life adventures of a young safari guide living in the Botswana bush, confronting the world's fiercest terrain and wildest animals and, most challenging of all, herds of gaping tourists. -

School Activities and Menus

FRIDAY MAY 22 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 KLBY/ABC News (N) Enter- Wife Swap Brown/ Supernanny Lewis 20/20 (CC) News (N) Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live H h (CC) tainment Neighbors (CC) Family (CC) (CC) (N) (CC) (N) (CC) KSNK/NBC News (N) Wheel of Howie Howie Dateline NBC (CC) News (N) The Tonight Show Late L j Fortune Do It Do It With Jay Leno (CC) Night KBSL/CBS News (N) Inside Ghost Whisperer Flashpoint Never NUMB3RS Scan News (N) Late Show With Late FRIDAY1< NX (CC) Edition (CC) Kissed a Girl (CC) Man (CC) (CC) David LettermanMAYLate22 K15CG The NewsHour Wash. Kansas Bill Moyers Journal Market- NOW on World New Red Charlie Rose (N) d With Jim Lehrer (N) Week Week (N) (CC) Market PBS (N) News Green (CC) ESPN Sports-6 PM NFL6:30 Live College7 PM Softball7:30: NCAA8 SuperPM Regional8:30 -- NCAA9 PM Baseball9:30 SportsCenter10 PM 10:30 (Live) Fast-11 PM Baseball11:30 O_ Center (N) (CC) Teams TBA. (Live) (CC) Update Tonight (CC) break Tonight KLBY/ABC News (N) Enter- Wife Swap Brown/ Supernanny Lewis 20/20 (CC) News (N) Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live HUSAh NCIS(CC) Untouchabletainment NCISNeighbors Probie (CC) (CC) NCISFamily Boxed (CC) In (CC) NCIS Angel of Death (CC)House Both(N) Sides (CC) (N)Movie: (CC) John P^ (CC) (CC) Now (CC) Grisham KSNK/NBC News (N) Wheel of Howie Howie Dateline NBC (CC) News (N) The Tonight Show Late LTBSj Seinfeld SeinfeldFortune FamilyDo It FamilyDo It Movie: What Women Want (2000) A chauvinistic ad WithMy Boys Jay LenoSex (CC)and NightSex and P_ (CC) (CC) Guy (CC) Guy (CC) executive can suddenly read women’s minds. -

RADARSCREEN Realscreen's Global Pitch Guide

US $7.95 USD Canada $8.95 CDN International $9.95 USUSDD RADARSCREEN realscreen’s Global Pitch Guide A USPS AFSM 100 Approved Polywrap A USPS AFSM 100 CANADA POST AGREEMENT NUMBER 40050265 PRINTED IN CANAD G<ID@KEF%+*-* 9L==8CF#EP L%J%GFJK8><G8@; 8LKF GIJIKJK; A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. RRS.19690.Breakthrough4.inddS.19690.Breakthrough4.indd 1 110/08/110/08/11 22:59:59 PPMM CONTENT SALES INTERNATIONAL THE SENSES MAKING SENSE OF THE WORLD AROUND US 3 x 50 min. | HD, 5.1 and stereo Just one of more than 30 new titles for 2011/2012 FOR MORE DOCUMENTARIES SEE contentsales.ORF.at WILDLIFE, NATURE & SCIENCE, ARCHITECTURE & DESIGN, CULTURE & ART, ENVIRONMENT & GLOBALIZATION, HISTORY & BIOGRAPHIES, LEISURE & LIFESTYLE, SOCIAL ISSUES & RELIGION, PEOPLE & PLACES RRS.19849.ORF.inddS.19849.ORF.indd 1 111/08/111/08/11 111:411:41 AAMM CONTENTS EDITOR’S NOTE . .4 UNITED STATES . .7 CANADA . 27 UNITED KINGDOM . 34 EUROPE . 40 AUSTRALIA . 48 ASIA . 50 INTERNATIONAL . 54 FUNDERS . 60 RADARSCREEN: realscreen’s Global Pitch Guide 3 CContentsEditPub.inddontentsEditPub.indd 3 111/08/111/08/11 22:36:36 PPMM ™ PITCH Realscreen is published 6 times a year by Brunico Communications Ltd., PERFECT 100- 366 Adelaide Street West, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5V 1R9 Tel. 416-408-2300 Fax 416-408-0870 www.realscreen.com elcome to the second annual edition of VP & Publisher Claire Macdonald [email protected] realscreen’s Global Pitch Guide, designed Editor Barry Walsh [email protected] to give producers and sellers of content the Associate Editor Adam Benzine [email protected] W Staff Writer Kelly Anderson [email protected] intel they need to fi nd the right buyers for their Creative Director Stephen Stanley [email protected] projects, and the information to help them shape Art Director Mark Lacoursiere [email protected] their pitches effectively. -

TRUE LIFE: Couple's Wedding Filmed for Reality TV

THE PENDULUM STYLE WEDNESDAY. MARCH 17. 2010 it PAGE 17 TRUE LIFE: Couple's wedding filmed for reality TV Sarah Carideo Coleman decided to be a part of “True Reporter Life.” She wanted to encourage and inspire other couples to think about It seems most of young America marriage in a different way and see is obsessed with reality shows about the benefits of waiting to live together lost love and broken marriages. and have sex until marriage. But the new season of MTV's “True Both of their families were nervous Life" will feature at least a tidbit of about the couple's participation in the true love. Viewers can keep their eyes show. peeled for an appearance from Elon “All they could think about was sophomore, Kellye Coleman, as her Jon and Kate Gosselin and they didn't sister is featured on “True Life: I'm a want the producers trying to put Will Newlywed." ii; ■ and 1 against each other to create After seeing Erica Coleman speak drama on television," Coleman said. at a retreat in fall 2005, Will Taylor After some questions were knew she was “wifey material.” answered, the families got on board He told his friend about this and preparations began. conclusion and word eventually Coleman is thankful there has been got back to Coleman. After hearing a year to plan the wedding, but said it about Taylor's claims, Coleman was was hard at times because of the long intrigued and found him on Facebook. distance the entire time. This has They started talking through the made her even more excited to finally networking site, and officially met in live in the same city as Taylor. -

MTV 'True Life' Features PJC Student

Member Texas Intercollegiate Press Association and Texas Community College Journalism Association The Bat “The Friendliest College In The South” Volume 85, No. 8, Thursday, April 22, 2010 AdairMTV opens up‘True and shares her Life’ story features PJC student about living with neurofibromatosis Stephanie norman bromatosis and his mother passed Editor away from neurofibromatosis. He had tumors on his face, which had Just like any typical 19-year- been there for years and he finally old, Amber Adair wants to wear found a doctor, at Medical City the latest fashions. That’s why she Dallas, who was willing to perform was thrilled to get a surgery that surgery, and remove the tumors would finally allow her to put on from both father and daughter in a pair of skinny jeans. December of last year. Adair, a freshman from Wolfe Adair said having her father’s City, is a student at the Paris Junior tumors removed the week before College Greenville campus. For hers by the same doctor, made the first time ever, she was able to her feel better about going into put on a pair of skinny jeans after surgery. her latest surgery Dec. 18, 2009, at “I got to bond with my dad,” which time, a 3-pound tumor was Adair said. “It made me feel a lot removed from her lower backside. better.” Adair has had nine surgeries After the removal of her tumor, since she was diagnosed with F1 Adair said she is more confident neurofibromatosis at a young age and outgoing. and is preparing for her tenth one “I didn’t like my tumor,” she scheduled for May 17. -

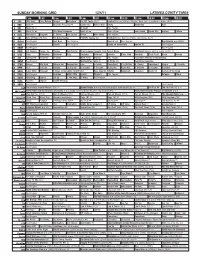

Sunday Morning Grid 12/4/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/4/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Danger Horseland The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Miami Dolphins. From Sun Life Stadium in Miami. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Willa’s Wild Skiing Swimming Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Explore Culture 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Prince Mike Webb Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Denver Broncos at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Bee Season ›› (2005) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Classic Gospel Special: Tent Revival Home Prohibition Groups push to outlaw alcohol. Å 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. -

Hanging of the Greens Holidays for Others

December 16, 2010 In This Issue… Program aims to aid soon-to-be-released prisoners By Nate Wisneski Mohican Indians, and the Kalihwisaks Great Lakes Inter-tribal A pilot program aimed Council (GLITC) will be at providing assistance to funded by the Second soon-to-be released Chance Act Adult and Native American prison- Juvenile Offender Re- ers is set to be imple- entry grant and plans to Wild Wild West – 9A mented in January of serve 100 individuals Sharon Skenandore next year. over three years. competes in Cowboy The Wisconsin Indian Oneida Business Mounting Shooting Tribal Community Committee Association. Reintegration Program Councilmember Melinda anticipates creating job Danforth, who serves on and housing opportuni- Governor Doyle’s Council for Re-Entry, ties to help reduce the echoed the project’s odds of prison re-entry goals. and help the transition “This project was into their communities. intended to reduce recidi- The agreement between vism of American Indian the Oneida Tribe, people as well as identi- Kali photo/Nate Wisneski Menominee Indian Tribe fying prudent services Representatives from the Oneida Tribe, Stockbridge-Munsee, and of Wisconsin, • See 7A, Menominee Tribe, and the GLITC sign the Wisconsin Indian Tribal Stockbridge-Munsee Re-entry assistance Community Band of Community Re-Integration Program Agreement. Christmas in the Community – 2B A look at community efforts to brighten the Hanging of the Greens holidays for others. Giving Tree – 9B The Oneida communi- ty and employees showed their generosi- ty at the Social Services Giving Tree. Kali photos/Yvonne Kaquatosh The cedar rope measures 100 ft. around the pillars in Section A the basement of the Holy Apostles Episcopal Church Pages 2–4A/Local Mission. -

The Paw Print August 2011

The official e-newsletter of The Barkley Pet Hotel & Day Spa The Paw Print August 2011 In This Issue: Barkley Makes Dog Fancy Barkley Makes Dog Fancy Magazine! Magazine! Dog Walking Advice from The Cleveland Clinic August's Pick of the Litter: Clyde Kertesz Click HERE to check out Barkley, our Casting Call: MTV True Life Golden Retriever mascot, dressed in Beat the Heat his summer gear for the July 2011 Canine Fun Days: Aug 20-21! pages of Dog Fancy magazine! Back To School Time August Poll: What type of food Dog Walking Advice from The Cleveland Clinic does your pet prefer? Click HERE According to a recent article published to take this month's survey! by The Cleveland Clinic: "Dog owners who walk their dogs every day are Vacation's aren't just for owners! Pets more likely to get the recommended love them, too! According to last amount of weekly exercise than non- month's poll about when your pet is dog owners." most likely to spend a vacation at The Barkley: "A Michigan study published this year in the Journal of Physical Activity and 38% said Winter/Holiday Break Health concluded that dog walkers 31% of guests visit during 4th have 34 percent higher odds of of July weekend obtaining at least 150 minutes per 15% answered Spring Break week of total walking than those who 15% vacation during Labor Day don't go walking with a pooch. They weekend also are 69 percent more likely to engage in other leisure-time activities." Tickle Your Funny Bone They went onto say, "It turns out people who walk their dogs overall have Two patients limp into different clinics better health and better heart health than people who have cats," says Marc with the same complaint. -

A 040909 Breeze Thursday

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Crushed Cape High loses 44-0 CAPE CORAL in spring game — SPORTS DAILY BREEZE WEATHER: Mostly Cloudy • Tonight: Storms • Saturday: Partly Sunny — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 119 Friday, May 22, 2009 50 cents Lee third-graders surpass state averages in FCAT “The third-grade results on this year’s Reading and math results released FCAT show that we are on the right track academically. This is great news, By MCKENZIE CASSIDY third-grade FCAT reading and math there’s much more to be done.” but we all know there’s much more to [email protected] tests Thursday. Lee County scores Scores from the state include all be done.” Schools in Lee County may be surpassed state averages in both students, including those enrolled in struggling with financial problems subjects and showed a clear exception education programs and — Superintendent James Browder due to budget shortfalls, but that has increase from three years ago. English language learners, and are not hindered some students’ aca- “The third-grade results on this used by the DOE to grade schools in demic achievements. year’s FCAT show that we are on the county. instruction and review. 76 percent earned a three or higher The Florida Department of the right track academically,” said Third-graders who receive a one The district reported that 81 per- on FCAT reading. Education released the results of the Superintendent James Browder. on the FCAT reading are required to cent of third-grade students earned a “This is great news, but we all know attend summer school for additional three or higher on FCAT math and See FCAT, page 6A Peace offering Building industry welcomes new Fla. -

When Podcast Met True Crime: a Genre-Medium Coevolutionary Love Story

Article When Podcast Met True Crime: A Genre-Medium Coevolutionary Love Story Line Seistrup Clausen Stine Ausum Sikjær 1. Introduction “I hear voices talking about murder... Relax, it’s just a podcast” — Killer Instinct Press 2019 Critics have been predicting the death of radio for decades, so when the new podcasting medium was launched in 2005, nobody believed it would succeed. Podcasting initially presented itself as a rival to radio, and it was unclear to people what precisely this new medium would bring to the table. As it turns out, radio and podcasting would never become rivals, as podcasting took over the role of audio storytelling medium – a role that radio had abandoned prior due to the competition from TV. During its beginning, technological limitations hindered easy access to podcasts, as they had to be downloaded from the Internet onto a computer and transferred to an MP3 player or an iPod. Meanwhile, it was still unclear how this new medium would come to satisfy an audience need that other types of storytelling media could not already fulfill. Podcasting lurked just below the mainstream for some time, yet it remained a niche medium for many years until something happened in 2014. In 2014, the true crime podcast Serial was released, and it became the fastest podcast ever to reach over 5 million downloads (Roberts 2014). After its release, podcasting entered the “post-Serial boom” (Nelson 2018; Van Schilt 2019), and the true crime genre spread like wildfire on the platform. Statistics show that the podcasting medium experienced a rise in popularity after 2014, with nearly a third of all podcasts listed on iTunes U.S. -

Waterways Film List

Water/Ways Film List This film resource list was assembled to help you research and develop programming around the themes of the WATER/WAYS exhibition. Work with your local library, a movie theater, campus/community film clubs to host films and film discussions in conjunction with the exhibition. This list is not meant to be exhaustive or even all-encompassing – it will simply get you started. A quick search of the library card catalogue or internet will reveal numerous titles and lists compiled by experts, special interest groups and film buffs. Host series specific to your region or introduce new themes to your community. All titles are available on DVD unless otherwise specified. See children’s book list for some of the favorite animated short films. Many popular films have blogs, on-line talks, discussion ideas and classroom curriculum associated with the titles. Host sites should check with their state humanities council for recent Council- funded or produced documentaries on regional issues. 20,000 Leagues under the Sea. 1954. Adventure, Drama, Family. Not Rated. 127 minutes. Based on the 1870 classic science fiction novel by Jules Verne, this is the story of the fictional Captain Nemo (James Mason) and his submarine, Nautilus, and an epic undersea exploration. The oceans during the late 1860’s are no longer safe; many ships have been lost. Sailors have returned to port with stories of a vicious narwhal (a giant whale with a long horn) which sinks their ships. A naturalist, Professor Pierre Aronnax (Paul Lukas), his assistant, Conseil (Peter Lorre), and a professional whaler, Ned Land (Kirk Douglas), join an US expedition which attempts to unravel the mystery.