The Joy of Storytelling: Incorporating Classic Art Styles with Visual Storytelling Techniques ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Major Exhibition of Stage Designs by Celebrated Cartoonist Gerald Scarfe

Gerald Scarfe: Stage and Screen At House of Illustration’s Main Gallery 22 September 2017 – 21 January 2018 The first major exhibition of stage designs by celebrated cartoonist Gerald Scarfe “I always want to bring my creations to life – to bring them off the page and give them flesh and blood, movement and drama.” – Gerald Scarfe "There is more to him than journalism... his elegantly grotesque, ferocious style remains instantly recognisable" – Evening Standard feature 20/09/17 Critics Choice – Financial Times 16/09/17 On 22 September 2017 House of Illustration opened the first major show of Gerald Scarfe’s striking production designs for theatre, rock, opera, ballet and film, many of which are being publicly exhibited for the very first time. Gerald Scarfe is the UK’s most celebrated political cartoonist; his 50-year-long career at The Sunday Times revealed an imagination that is acerbic, explosive and unmistakable. But less well known is Scarfe’s lifelong contribution to the performing arts and his hugely significant work beyond the page, designing some of the most high-profile productions of the last 30 years. This exhibition is the first to explore Scarfe’s extraordinary work for stage and screen. It features over 100 works including preliminary sketches, storyboards, set designs, photographs, ephemera and costumes from productions including Orpheus in the Underworld at English National Opera, The Nutcracker by English National Ballet and Los Angeles Opera’s The Magic Flute. It also shows his 1994 work as the only ever external Production Designer for Disney, for their feature film Hercules, as well as his concept, character and animation designs for Pink Floyd’s 1982 film adaptation of The Wall. -

Creating Manga-Style Artwork in Corel Painter X

Creating manga-style artwork in Corel® Painter™ X Jared Hodges Manga is the Japanese word for comic. Manga-style comic books, graphic novels, and artwork are gaining international popularity. Bronco Boar, created by Jared Hodges in Corel Painter X The inspiration for Bronco Boar comes from my interest in fantastical beasts, Mesoamerican design motifs, and my background in Japanese manga-style imagery. In the image, I wanted to evoke a feeling of an American Southwest desert with a fantasy twist. I came up with the idea of an action scene portraying a cowgirl breaking in an aggressive oversized boar. In this tutorial, you will learn about • character design • creating a rough sketch of the composition • finalizing line art • the coloring process • adding texture, details, and final colors 1 Character Design This picture focuses on two characters: the cowgirl and the boar. I like to design the characters before I work on the actual image, so I can concentrate on their appearance before I consider pose and composition. The cowgirl's costume was inspired by western clothing: cowboy hat, chaps, gloves, and boots. I added my own twist to create a nontraditional design. I enlisted the help of fellow artist and partner, Lindsay Cibos, to create a couple of conceptual character designs based on my criteria. Two concept sketches by Lindsay Cibos. These sketches helped me decide which design elements and colors to use for the character's outfit. Combining our ideas, I sketched the final design using a custom 2B Pencil variant from the Pencils category, switching between a size of 3 pixels for detail work and 5 pixels for broader strokes. -

Texture Mapping for Cel Animation

Texture Mapping for Cel Animation 1 2 1 Wagner Toledo Corrˆea1 Robert J. Jensen Craig E. Thayer Adam Finkelstein 1 Princeton University 2 Walt Disney Feature Animation (a) Flat colors (b) Complex texture Figure 1: A frame of cel animation with the foreground character painted by (a) the conventional method, and (b) our system. Abstract 1 INTRODUCTION We present a method for applying complex textures to hand-drawn In traditional cel animation, moving characters are illustrated with characters in cel animation. The method correlates features in a flat, constant colors, whereas background scenery is painted in simple, textured, 3-D model with features on a hand-drawn figure, subtle and exquisite detail (Figure 1a). This disparity in render- and then distorts the model to conform to the hand-drawn artwork. ing quality may be desirable to distinguish the animated characters The process uses two new algorithms: a silhouette detection scheme from the background; however, there are many figures for which and a depth-preserving warp. The silhouette detection algorithm is complex textures would be advantageous. Unfortunately, there are simple and efficient, and it produces continuous, smooth, visible two factors that prohibit animators from painting moving charac- contours on a 3-D model. The warp distorts the model in only two ters with detailed textures. First, moving characters are drawn dif- dimensions to match the artwork from a given camera perspective, ferently from frame to frame, requiring any complex shading to yet preserves 3-D effects such as self-occlusion and foreshortening. be replicated for every frame, adapting to the movements of the The entire process allows animators to combine complex textures characters—an extremely daunting task. -

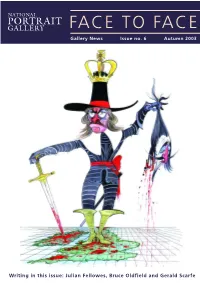

FACE to FACE Gallery News Issue No

P FACE TO FACE Gallery News Issue no. 6 Autumn 2003 Writing in this issue: Julian Fellowes, Bruce Oldfield and Gerald Scarfe FROM THE DIRECTOR The autumn exhibition Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits offers an unusual opportunity to see fascinating images of those who usually remain invisible. The exhibition offers intriguing stories of the particular individuals at the centre of great houses, colleges or business institutions and reveals the admiration and affection that caused the commissioning of a portrait or photograph. We are also celebrating the completion of the new scheme for Trafalgar Square with the young people’s education project and exhibition, Circling the Square, which features photographs that record the moments when the Square has acted as a touchstone in history – politicians, activists, philosophers and film stars have all been photographed in the Square. Photographic portraits also feature in the DJs display in the Bookshop Gallery, the Terry O’Neill display in the Balcony Gallery and the Schweppes Photographic Portrait Prize launched in November in the Porter Gallery. Gerald Scarfe’s rather particular view of the men and women selected for the Portrait Gallery is published at the end of September. Heroes & Villains, is a light hearted and occasionally outrageous view of those who have made history, from Elizabeth I and Oliver Cromwell to Delia Smith and George Best. The Gallery is very grateful for the support of all of its Patrons and Members – please do encourage others to become Members and enjoy an association with us, or consider becoming a Patron, giving significant extra help to the Gallery’s work and joining a special circle of supporters. -

Guide to Digital Art Specifications

Guide to Digital Art Specifications Version 12.05.11 Image File Types Digital image formats for both Mac and PC platforms are accepted. Preferred file types: These file types work best and typically encounter few problems. tif (TIFF) jpg (JPEG) psd (Adobe Photoshop document) eps (Encapsulated PostScript) ai (Adobe Illustrator) pdf (Portable Document Format) Accepted file types: These file types are acceptable, although application versions and operating systems can introduce problems. A hardcopy, for cross-referencing, will ensure a more accurate outcome. doc, docx (Word) xls, xlsx (Excel) ppt, pptx (PowerPoint) fh (Freehand) cdr (Corel Draw) cvs (Canvas) Image sizing specifications should be discussed with the Editorial Office prior to digital file submission. Digital images should be submitted in the final size desired. White space around the image should be removed. Image Resolution The minimum acceptable resolution is 200 dpi at the desired final size in the paged article. To ensure the highest-quality published image, follow these optimum resolutions: • Line = 1200 dpi. Contains only black and white; no shades of gray. These images are typically ink drawings or charts. Other common terms used are monochrome or 1-bit. • Grayscale or Color = 300 dpi. Contains no text. A photograph or a painting is an example of this type of image. • Combination = 600 dpi. Grayscale or color image combined with a line image. An example is a photograph with letter labels, arrows, or text added outside the image area. Anytime a picture is combined with type outside the image area, the resolution must be high enough to maintain smooth, readable text. -

A Comparative Study on Films of Vincent Van Gogh

A Dissertation On PAINTING LIFE FROM CINEMA : A COMPARATIVE STUDY ON FILMS OF VINCENT VAN GOGH Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement of BA Journalism & Mass Communication program of Navrachana University during the year 2017-2020 By RIYA KHOYANI Semester VI 17165018 Under the guidance of Dr. JAVED KHATRI NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 Certificate Awarded to RIYA KHOYANI This is to certify that the dissertation titled PAINTING LIFE FROM CINEMA : A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FILMS ON VINCENT VAN GOGH has been submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirement of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program of Navrachana University. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation titled, Painting life from cinema : A comparative study of films on Vincent van Gogh prepared and submitted by RIYA KHOYANI of Navrachana University, Vadodara in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program is hereby accepted. Place: Vadodara Date: 15-05-2020 Dr. Javed Khatri Dissertation Guide Dr. Robi Augustine Program Chair Accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. Place: Vadodara Date: 15-05-2020 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation titled “ Painting life from cinema : A comparative study of films on Vincent van Gogh” is an original work prepared and written by me, under the guidance of Mrs/Mr/Dr Javed Khatri Assistant Professor, Journalism and Mass Communication program, Navrachana University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Scarfe the Wall Live Tour Group.Pages

THE ART OF FROM PINK FLOYD THE WALL PRESENTED BY ROGER WATERS THE WALL LIVE TOUR ARTWORK CATALOGUE THE ART OF GERALD SCARFE - FROM PINK FLOYD THE WALL SAN FRANCISCO ART EXCHANGE LLC Image © Gerald Scarfe Image © Gerald Scarfe Roger Waters, c.2010 The Mother, c.2010 Pen, Ink & Watercolour on Paper Pen, Ink & Watercolour on Paper 33” x 23 ¼” sheet size 32” x 22 ¾” sheet size This illustration of Roger Waters on his The Wall Live A recent concept design, done for Roger Water’s tour (2010-2013) appeared on the front cover of The Wall Live tour (2010-2013) that was based on a Billboard Magazine 24 July, 2012. similar scene in the flm shown during the song The Trial where The Mother morphs into a giant protective wall surrounding a baby Pink. 458 GEARY STREET • SAN FRANCISCO CA 94102 • sfae.com • 415.441.8840 main THE ART OF GERALD SCARFE - FROM PINK FLOYD THE WALL SAN FRANCISCO ART EXCHANGE LLC Image © Gerald Scarfe Crazy Toys in the Attic, c.2010 Watercolor, Pen & Ink Collage on Paper 23 ¼” x 33” sheet size Image © Gerald Scarfe Go On Judge, Shit on Him! c.2010 This drawing is based on a segment of the animated scene of The Trial in The Wall flm. As the line “Crazy…Toys in the Pen, Ink & Watercolour on Paper Attic, I am crazy” is sung, the viewer sees a terrifed Pink 32 ½” x 22 ½” sheet size fade to grey as the camera zooms in on his eye until the scene fades into the next animation sequence. -

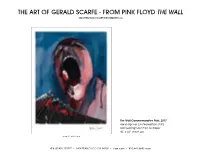

Scarfe Wall Print.Pages

THE ART OF GERALD SCARFE - FROM PINK FLOYD THE WALL SAN FRANCISCO ART EXCHANGE LLC The Wall Commemorative Print, 2017 Hand-Signed, Limited edition (100) Archival Pigment Print on Paper 40” x 30” sheet size Image © Gerald Scarfe 458 GEARY STREET • SAN FRANCISCO CA 94102 • sfae.com • 415.441.8840 main THE ART OF GERALD SCARFE - FROM PINK FLOYD THE WALL SAN FRANCISCO ART EXCHANGE LLC ABOUT THE PRINT This powerful, large-format limited-edition artwork combines two iconic Gerald Scarfe paintings - The Scream and Giant Judge and Marching Hammers - into a stunningly vibrant and expressive work of art. The Scream painting was most notably used for the film poster and is now the most iconic image from the project. It features the main character of the album and film, ‘Pink’ who is illustrated in a rough, expressionistic style. His head is tilted up toward the sky and his mouth hangs wide open in a deeply animalistic and nearly perceptible scream. Pink is based on both Roger Waters (who wrote the songs based in part on his own experiences) and Syd Barrett, both distinctive artists and founding members of Pink Floyd. In the story narrative, Pink is struggling with the pressures and angst of existence in a world of competing hedonistic desires, fame and fortune, and the effects of first-hand experiences of war as a child. The Giant Judge and Marching Hammers painting captures the overall atmosphere of the album and film. It features the mesmerizing marching 'Crossed Hammers' motif that became synonymous with oppressive regimes and over-reaching and extreme governmental power. -

Tate Report 2010–2011

Tate Report 2010–11 Contents Introduction 3 Collection Developing the Collection 9 Caring for the Collection 11 Research 13 Acquisition highlights 16 Programme Tate Britain 35 Tate Modern 38 Tate Liverpool 40 Tate St Ives 43 Programme calendar 46 Audiences Engaging audiences 48 Online and media 52 Sharing with the nation 55 Looking abroad 57 Improving Tate Staff and sustainability 60 Funding and trading 62 Future Developments Building for the future 67 Financial Review 70 Donations, Gifts, Legacies and Sponsorships 73 Tate Report 10–11 2 Introduction Tate’s purpose is to enrich people’s lives through their encounter with art. The relationship between museums and audiences evolves over time and continues to change because of the impact of new technology and more demanding public expectations. Tate embraces this change across the spectrum of its activity. Sharing new insights Tate’s work is founded on rigorous research, ranging from the development of leading-edge conservation techniques to informing Tate’s learning practice and presenting familiar artists in a new light. Such perspectives were evident this year in the exhibitions Gauguin: Maker of Myth, Henry Moore, Picasso: Peace and Freedom and Peter Lanyon. Research also contributes to the development of the Collection and its display, as does the dialogue with colleagues around the world – from Asia and Africa, to the Middle East and South America. The resulting expertise forms the basis of a broadening understanding of art history, which in turn shapes Tate’s acquisitions and the character of the Collection. Important works were acquired this year by artists including Pak Sheung Chuen, Jimmie Durham, Boris Mikhailov, Felix Gonzales- Torres and Do Ho Suh. -

Vincent/Regional/De/Loving-Vincent

Presseheft Praesens-Film präsentiert EIN FILM VON DOROTA KOBIELA UND HUGH WELCHMAN AB DEM 28. DEZEMBER 2017 IM KINO Biopic, Animation / UK, Polen / Dauer: 95 Minuten VERLEIH PRESSE Praesens-Film AG Olivier Goetschi Münchhaldenstrasse 10 Pro Film GmbH 8034 Zürich [email protected] [email protected] T: +41 44 433 38 32 T: +41 44 325 35 24 Tamara Araimi Praesens-Film AG [email protected] T: +41 44 422 38 35 Pressematerial und weitere Infos zum Film unter www.praesens.com Regie Dorota Kobiela, Hugh Welchman Drehbuch Dorota Kobiela, Hugh Welchman, Jacek Dehnel Produzenten Hugh Welchman, Ivan Mactaggart, Sean Bobbitt Kamera Tristan Oliver, Łukasz Żal Schnitt Justyna Wierszyńska, Dorota Kobiela Musik Clint Mansell Darsteller Douglas Booth (Armand Roulin) Chris O’Dowd (Joseph Roulin) Saoirse Ronan (Marguerite Gachet) Jerome Flynn (Dr. Gachet) Eleanor Tomlinson (Adeline Ravoux) John Sessions (Pere Tanguy) Helen McCrory (Louise Chevalier) Aidan Turner (Bootsmann) Robert Gulaczyk (Vincent van Gogh) Kurzinhalt Ein Jahr nach dem Tod Vincent van Goghs taucht plötzlich ein Brief des Künstlers an dessen Bruder Theo auf. Der junge Armand Roulin erhält den Auftrag, den Brief auszuhändigen. Zunächst widerwillig macht er sich auf den Weg, doch je mehr er über Vincent erfährt, desto faszinierender erscheint ihm der Maler, der zeit seines Lebens auf Unverständnis und Ablehnung stieß. War es am Ende gar kein Selbstmord? Entschlossen begibt sich Armand auf die Suche nach der Wahrheit. Pressenotiz LOVING VINCENT erweckt die einzigartigen Bilderwelten van Goghs zum Leben: 125 Künstler aus aller Welt kreierten mehr als 65.000 Einzelbilder für den ersten vollständig aus Ölgemälden erschaffenen Film. Entstanden ist ein visuell berauschendes Meisterwerk, dessen Farbenpracht und Ästhetik noch lange nachwirken. -

Learning to Shadow Hand-Drawn Sketches

Learning to Shadow Hand-drawn Sketches Qingyuan Zheng∗1, Zhuoru Li∗2, and Adam Bargteil1 1University of Maryland, Baltimore County 2Project HAT fqing3, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract We present a fully automatic method to generate detailed and accurate artistic shadows from pairs of line drawing sketches and lighting directions. We also contribute a new dataset of one thousand examples of pairs of line draw- ings and shadows that are tagged with lighting directions. Remarkably, the generated shadows quickly communicate the underlying 3D structure of the sketched scene. Con- sequently, the shadows generated by our approach can be used directly or as an excellent starting point for artists. We demonstrate that the deep learning network we propose takes a hand-drawn sketch, builds a 3D model in latent space, and renders the resulting shadows. The generated shadows respect the hand-drawn lines and underlying 3D space and contain sophisticated and accurate details, such Figure 1: Top: our shadowing system takes in a line drawing and as self-shadowing effects. Moreover, the generated shadows a lighting direction label, and outputs the shadow. Bottom: our contain artistic effects, such as rim lighting or halos ap- training set includes triplets of hand-drawn sketches, shadows, and pearing from back lighting, that would be achievable with lighting directions. Pairs of sketches and shadow images are taken traditional 3D rendering methods. from artists’ websites and manually tagged with lighting directions with the help of professional artists. The cube shows how we de- note the 26 lighting directions (see Section 3.1). c Toshi, Clement 1.