A Photographic Ontology: Being Haunted Within the Blue Hour and Expanding Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

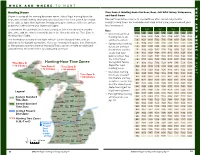

Hunting Hours Time Zone A

WHEN AND WHERE TO HUNT WHEN AND WHERE Hunting Hours Time Zone A. Hunting Hours for Bear, Deer, Fall Wild Turkey, Furbearers, Shown is a map of the hunting-hour time zones. Actual legal hunting hours for and Small Game bear, deer, fall wild turkey, furbearer, and small game for Time Zone A are shown One-half hour before sunrise to one-half hour after sunset (adjusted for in the table at right. Hunting hours for migratory game birds are different and are daylight saving time). For hunt dates not listed in the table, please consult your published in the current-year Waterfowl Digest. local newspaper. 2016 Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. To determine the opening (a.m.) and closing (p.m.) time for any day in another Note: time zone, add the minutes shown below to the times listed in the Time Zone A • Woodcock and teal Date AM PM AM PM AM PM AM PM Hunting Hours Table. hunting hours are 1 6:28 8:35 7:00 7:43 7:36 6:55 7:12 5:31 The hunting hours listed in the table reflect Eastern Standard Time, with an sunrise to sunset. 2 6:29 8:34 7:01 7:41 7:38 6:54 7:14 5:30 adjustment for daylight saving time. If you are hunting in Gogebic, Iron, Dickinson, • Spring turkey hunting 3 6:30 8:32 7:02 7:39 7:39 6:52 7:15 5:30 or Menominee counties (Central Standard Time), you must make an additional hours are one-half 4 6:31 8:30 7:03 7:38 7:40 6:51 7:16 5:30 adjustment to the printed time by subtracting one hour. -

Daylight Saving Time (DST)

Daylight Saving Time (DST) Updated September 30, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45208 Daylight Saving Time (DST) Summary Daylight Saving Time (DST) is a period of the year between spring and fall when clocks in most parts of the United States are set one hour ahead of standard time. DST begins on the second Sunday in March and ends on the first Sunday in November. The beginning and ending dates are set in statute. Congressional interest in the potential benefits and costs of DST has resulted in changes to DST observance since it was first adopted in the United States in 1918. The United States established standard time zones and DST through the Calder Act, also known as the Standard Time Act of 1918. The issue of consistency in time observance was further clarified by the Uniform Time Act of 1966. These laws as amended allow a state to exempt itself—or parts of the state that lie within a different time zone—from DST observance. These laws as amended also authorize the Department of Transportation (DOT) to regulate standard time zone boundaries and DST. The time period for DST was changed most recently in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPACT 2005; P.L. 109-58). Congress has required several agencies to study the effects of changes in DST observance. In 1974, DOT reported that the potential benefits to energy conservation, traffic safety, and reductions in violent crime were minimal. In 2008, the Department of Energy assessed the effects to national energy consumption of extending DST as changed in EPACT 2005 and found a reduction in total primary energy consumption of 0.02%. -

Impact of Extended Daylight Saving Time on National Energy Consumption

Impact of Extended Daylight Saving Time on National Energy Consumption TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION FOR REPORT TO CONGRESS Energy Policy Act of 2005, Section 110 Prepared for U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy By David B. Belzer (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory), Stanton W. Hadley (Oak Ridge National Laboratory), and Shih-Miao Chin (Oak Ridge National Laboratory) October 2008 U.S. Department of Energy Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Page Intentionally Left Blank Acknowledgements The Department of Energy (DOE) acknowledges the important contributions made to this study by the principal investigators and primary authors—David B. Belzer, Ph.D (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory), Stanton W. Hadley (Oak Ridge National Laboratory), and Shih-Miao Chin, Ph.D (Oak Ridge National Laboratory). Jeff Dowd (DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy) was the DOE project manager, and Margaret Mann (National Renewable Energy Laboratory) provided technical and project management assistance. Two expert panels provided review comments on the study methodologies and made important and generous contributions. 1. Electricity and Daylight Saving Time Panel – technical review of electricity econometric modeling: • Randy Barcus (Avista Corp) • Adrienne Kandel, Ph.D (California Energy Commission) • Hendrik Wolff, Ph.D (University of Washington) 2. Transportation Sector Panel – technical review of analytical methods: • Harshad Desai (Federal Highway Administration) • Paul Leiby, Ph.D (Oak Ridge National Laboratory) • John Maples (DOE Energy Information Administration) • Art Rypinski (Department of Transportation) • Tom White (DOE Office of Policy and International Affairs) The project team also thanks Darrell Beschen (DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy), Doug Arent, Ph.D (National Renewable Energy Laboratory), and Bill Babiuch, Ph.D (National Renewable Energy Laboratory) for their helpful management review. -

How the Sun Paints the Sky the Generation of Its Colour and Luminosity Bob Fosbury European Southern Observatory and University College London

How the Sun Paints the Sky The generation of its colour and luminosity Bob Fosbury European Southern Observatory and University College London Introduction: the 19th century context — science and painting The appearance of a brilliantly clear night sky must surely have stimulated the curiosity of our earliest ancestors and provided them with the foundation upon which their descendants built the entire edifice of science. This is a conclusion that would be dramatically affirmed if any one of us were to look upwards in clear weather from a location that is not polluted by artificial light: an increasingly rare possibility now, but one that provides a welcome regeneration of the sense of wonder. What happened when our ancient ancestors gazed instead at the sky in daylight or twilight? It is difficult to gauge from written evidence as there was such variation in the language of description among different cultures (see “Sky in a bottle” by Peter Pesic. MIT Press, 2005. ISBN 0-262-16234-2). The blue colour of a cloudless sky was described in a remarkable variety of language, but the question of its cause most often remained in the realm of a superior being. Its nature did concern the Greek philosophers but they appeared to describe surfaces and objects in the language of texture rather than colour: they did not have a word for blue. It was only during the last millennium that thinkers really tried to get to grips with the problem, with Leonardo da Vinci, Isaac Newton and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe all applying themselves. It was not easy however, and no real progress was made until the mid-19th century when there was a focus of the greatest scientific minds of the time on the problem of both the colour and the what was then the novel property of polarisation of the light. -

Serene Timer B Programming

Timer Mode B - 24 Hour ON/OFF Time with Full Light Cycle Timer B Mode allows you to program the Serene LED aquarium light with daily Sunrise, Daylight, Sunset and Moonlight, In addition, the background light and audio can also be programmed to run daily along with Daylight. Serene’s Timer B program consists of four photoperiods: Sunrise - 15min ramp into a 1 hour color spectrum, followed by 15min ramp to Daylight Daylight - color spectrum runs until OFF time is reached. (Background light & audio optional.) Sunset - 15min dim into a 1 hour color spectrum, followed by 15min dim to Moonlight Moonlight - runs a color spectrum for 6 hrs., then turns off The below diagram shows the default Timer B program installed with Serene: ON TIME: 07:00 OFF TIME: 17:00 (Light begins to turn on at 7:00am) (Light begins to turn o at 5:00 pm) PREPROGRAMMED DEFAULT: Sunrise/Sunset Color: R-75%, G-5%, B-75%, W-50% Daylight Color: R-100%, G-100%, B-100%, W-100% Background Light: Blue-Orange Fade Audio: Stream, 50% Volume Moonlight Color: R-5%, G-0%, B-10%, W-0% “M”: 100% Red Programming Instructions: There are 4 basic steps to programming Serene in Timer B Mode: STEP 1: Programming Clock & ON/OFF TImes STEP 2: Setting & Adjusting Sunrise/Sunset, Daylight, Moonlight Color Spectrums STEP 3: Programming Background Light & Audio Programs STEP 4: Confirming Timer B Mode Setting 1 Programming Instructions: STEP 1: Programming Clock, Daily ON & OFF Time a. Setting Clock (Time is in 24:00 Hrs) 1. Press: SET CLOCK - Controller Displays: “S-CL” 2. -

Sky Watch Heard Most Weekdays on WFWM, FSU's Public Supported

Night Highlights – Dec.2014 through Dec.2015 by Dr. Bob Doyle, Frostburg State Planetarium Dr. Doyle’s email is: [email protected]: His office phone number is (301) 687-7799 MOON – Earth’s companion both orbits Earth and rotates in 27.32 E. days so one side of moon always faces Earth (while other side is turned away from us). Moon’s cycle of lighted shapes (phases) lasts 29.53 E. days, as the phases also depend on direction of sun (appears to move 30 degrees eastward each month along zodiac). The moon is seen about 13 days growing in the evening from a slender crescent ( ) ) to Full, followed by an equal time shrinking (mainly seen in the a.m. sky) and then 3 days hidden in sun’s glare. Key Moon Phases (D) moon ½ full in evening (best for crater & mountain viewing ) & (O) full moon (see all lava plains) (Dec. ’14, 6 -O, 28 – D)) // (Jan. ’15, 4 - O, 26 - D), // (Feb. ’15, 3 – O, 25 - D) // (Mar. 5 – O, 27 – D) (Apr. 4 – O, 25 – D), // ( May 3 – O, 25 - D) // (Jun., 2- O, 27 – D)) // (Jul., 1 – O, 24 –D, 31 –O (Blue Moon)) (Aug., 22 – D, 29 – O) // (Sep., 20 – D, 27 – O (Harvest Moon)) // (Oct. 20 – D, 27 – O (Hunters’ Moon)) // (Nov., 19 – D, 25 – O) // (Dec., 18 – D, 25 – O (Long Night Moon)) (D = ½ full, O = full) THE 5 BRIGHT PLANETS (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter & Saturn): Uranus, Neptune are much dimmer. When high above horizon, planets appear as points of light that shine steadily. -

The Blue Hours Dusk, Early September, Just Beneath the Arctic

The Blue Hours Dusk, early September, just beneath the Arctic Circle, by a tideline glacier in East Greenland. The cusp of the seasons, the cusp of the globe, the cusp of the land, and the day’s cusp too: twilight, the blue hours. At this latitude, at this time of year, dusk lasts for two or three hours. We have returned from a long mountain day: pitched climbing up steep slabs and over snow slopes to a towered summit, from which height we could see the great inland ice-cap itself. Then down, late in the day, the darkness thickening around us, and the sun dropping fast behind the western peaks. So we sit together back at camp as the last light gathers on the water of the fjord, on icebergs, on the quartz seams in the white boulder-field above our tents. Twilight specifies the landscape in this way – but it also disperses it. Relations between objects are loosened, such that shape-shifts occur. Just before full night falls, and the aurora borealis begins, a powerful hallucination occurs. My tired eyes start to see every pale stone around our tent not as boulder but as bear, polar bear, pure bear, crouched for the spring. Across the Northern hemisphere, twilight is known as the trickster-time: breeder of delusion, feeder of fantasies, zone of becomings. In Greek, dusk is called lykophos, ‘wolf-light’. In Austria, too, it is Wolflicht. In French it is the phase entre chien et loup, ‘between dog and wolf’: the time when, as Chrystel Lebas has written, ‘it is nearly impossible to tell the difference between the howling sound coming from the two animals, when the domestic and familiar transform into the wild.’ I do not know the Greenlandic word for dusk, but perhaps it would translate as ‘bear-light’. -

The Golden Hour Refers to the Hour Before Sunset and After Sunrise

TheThe GoldenGolden HourHour The Golden Hour refers to the hour before sunset and after sunrise. Photographers agree that some of the very best times of day to take photos are during these hours. During the Golden Hours, the atmosphere is often permeated with breathtaking light that adds ambiance and interest to any scene. There can be spectacular variations of colors and hues ranging from subtle to dramatic. Even simple subjects take on an added glow. During the Golden Hours, take photos when the opportunity presents itself because light changes quickly and then fades away. 07:14:09 a.m. 07:15:48 a.m. Photographed about 60 seconds after previous photo. The look of a scene can vary greatly when taken at different times of the day. Scene photographed midday Scene photographed early morning SampleSample GoldenGolden HourHour photosphotos Top Tips for taking photos during the Golden Hours Arrive on the scene early to take test shots and adjust camera settings. Set camera to matrix or center-weighted metering. Use small apertures for maximizing depth-of-field. Select the lowest possible ISO. Set white balance to daylight or sunny day. When lighting is low, use a tripod with either a timed shutter release (self-timer) or a shutter release cable or remote. Taking photos during the Golden Hours When photographing the sun Don't stare into the sun, or hold the camera lens towards it for a very long time. Meter for the sky but don't include the sun itself. Composition tips: The horizon line should be above or below the center of the scene. -

Excerpts from Dusk of Dawn: an Essay Toward an Autobiography Of

DUSK OF DAWN An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept W. E. B. Du Bois Series Editor, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Introduction by K. Anthony Appiah OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Contents SERIES INTRODUCTION: THE BLACK LETTERS ON THE SIGN xi INTRODUCTION xxv APOLOGY xxxiii I. THEPLOT 1 II. A NEW ENGLAND BOY AND RECONSTRUCTION 4 III. EDUCATION IN THE LAST DECADES OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY 13 IV. SCIENCE AND EMPIRE 26 V. THE CONCEPT OF RACE 49 VI. THE WHITE WORLD 68 VII. THE COLORED WORLD WITHIN 88 VIII. PROPAGANDA AND WORLD WAR 111 IX. REVOLUTION 134 INDEX 163 WILLIAM EDWARD BURGHARDT DUBOIS: A CHRONOLOGY 171 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 ix CHAPTER VII The Colored World Within Not only do white men but also colored men forget the facts of the Negro's dou ble environment. The Negro American has for his environment not only the white surrounding world, but also, and touching him usually much more nearly and compellingly, is the environment furnished by his own colored group. There are exceptions, of course, but this is the rule. The American Negro, therefore, is surrounded and conditioned by the concept which he has of white people and he is treated in accordance with the concept they have of him. On the other hand, so far as his own people are concerned, he is in direct contact with individuals and facts. He fits into this environment more or less willingly. It gives him a social world and mental peace. On the other hand and especially if in education and ambition and income he is above the average culture of his group, he is often resentful of its environilcg power; partly because he does not recognize its power and partly because he is determined to consider himself part of the white group from which, in fact, he is excluded. -

Exploring Solar Cycle Influences on Polar Plasma Convection

Comparison of Terrestrial and Martian TEC at Dawn and Dusk during Solstices Angeline G. Burrell1 Beatriz Sanchez-Cano2, Mark Lester2, Russell Stoneback1, Olivier Witasse3, Marco Cartacci4 1Center for Space Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas 2Radio and Space Plasma Physics, University of Leicester 3European Space Agency, ESTEC – Scientific Support Office 4Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali 52nd ESLAB Symposium Outline • Motivation • Data and analysis – TEC sources – Data selection – Linear fitting • Results – Martian variations – Terrestrial variations – Similarities and differences • Conclusions Motivation • The Earth and Mars are arguably the most similar of the solar planets - They are both inner, rocky planets - They have similar axial tilts - They both have ionospheres that are formed primarily through EUV and X- ray radiation • Planetary differences can provide physical insights Total Electron Content (TEC) • The Global Positioning System • The Mars Advanced Radar for (GPS) measures TEC globally Subsurface and Ionosphere using a network of satellites and Sounding (MARSIS) measures ground receivers the TEC between the Martian • MIT Haystack provides calibrated surface and Mars Express TEC measurements • Mars Express has an inclination - Available from 1999 onward of 86.9˚ and a period of 7h, - Includes all open ground and allowing observations of all space-based sources locations and times - Specified with a 1˚ latitude by 1˚ • TEC is available for solar zenith longitude resolution with error estimates angles (SZA) greater than 75˚ Picardi and Sorge (2000), In: Proc. SPIE. Eighth International Rideout and Coster (2006) doi:10.1007/s10291-006-0029-5, 2006. Conference on Ground Penetrating Radar, vol. 4084, pp. 624–629. -

Planit! User Guide

ALL-IN-ONE PLANNING APP FOR LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHERS QUICK USER GUIDES The Sun and the Moon Rise and Set The Rise and Set page shows the 1 time of the sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset on a day as A sunrise always happens before a The azimuth of the Sun or the well as their azimuth. Moon is shown as thick color sunset on the same day. However, on lines on the map . some days, the moonset could take place before the moonrise within the Confused about which line same day. On those days, we might 3 means what? Just look at the show either the next day’s moonset or colors of the icons and lines. the previous day’s moonrise Within the app, everything depending on the current time. In any related to the Sun is in orange. case, the left one is always moonrise Everything related to the Moon and the right one is always moonset. is in blue. Sunrise: a lighter orange Sunset: a darker orange Moonrise: a lighter blue 2 Moonset: a darker blue 4 You may see a little superscript “+1” or “1-” to some of the moonrise or moonset times. The “+1” or “1-” sign means the event happens on the next day or the previous day, respectively. Perpetual Day and Perpetual Night This is a very short day ( If further north, there is no Sometimes there is no sunrise only 2 hours) in Iceland. sunrise or sunset. or sunset for a given day. It is called the perpetual day when the Sun never sets, or perpetual night when the Sun never rises.