On Defining the Tabloid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fp178a:Free Press Template Changed Fonts.Qxd.Qxd

fp178a:Free Press template changed fonts.qxd 24/10/2010 12:08 Page 1 FREE Press No 178 September-October 2010 £1 Journal of the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom BBC FALLS ROB SAFAR Letters to Cable ON TORIES’ from right, left and centre SWORD ELEANOR CAMPION, a volunteer with the campaigning group 38 Degrees, handed HE FUTURE of the BBC under the S4C was planning to cut 25 per cent of in a 19,000-signatory letter at Business ConDem coalition government was staff. Secretary Vince Cable’s office in London determined in October as the cor- The BBC must also underwrite the on October 8 (above). poration accepted a 16 per cent roll-out of the digital radio network. In Its message, 38 Degrees said, was that spending cut, offering no resist- present terms the extra costs were sum- “we’d all be behind him if he decides to Tance and pre-empting any campaign on marised at £340 million a year. stop Rupert Murdoch’s BSkyB power its behalf. The battle was brief, one-sided and grab.” A six-year freeze in the licence fee and decisive. In its trepidation the BBC had The CPBF got together with 38 the imposition of additional liabilities already offered to freeze the licence fee Degrees to launch the online petition, will put increasing pressure on program- for two years – an offer the government which asked Vince Cable to call in the ming and the corporation’s public service gratefully accepted – but was then con- anticipated bid from the Murdochs’ News obligations. -

PRIME MINISTER 11 May 2010

PRIME MINISTER 11 May 2010 – 15 July 2011 Meeting with proprietors, editors and senior media executives Prime Minister, The Rt Hon David Cameron MP Date of Name of individual/s Purpose of Meeting Meeting May 2010 Rupert Murdoch (News Corp) General discussion May 2010 Paul Dacre (Daily Mail) General discussion May 2010 Lord (Terry) Burns (C4) Chequers May 2010 Deborah Turness (ITV news) Chequers June 2010 Rebekah Brooks (News Chequers International) June 2010 Dominic Mohan (Sun) General discussion June 2010 News International summer Social party June 2010 James Harding (Times) Interview June 2010 Geordie Greig (Evening General discussion Standard) June 2010 Times CEO Summit Speech June 2010 FT mid-summer party Social July 2010 Spectator summer party Social July 2010 Aidan Barclay (Telegraph General discussion Media Group) July 2010 National Broadcasters and Reception (No 10) Lobby July 2010 The Sun Police Bravery Awards ceremony Awards Reception and Dinner July 2010 Lord (Jonathan) Rothermere Chequers July 2010 Tony Gallagher (Telegraph) General discussion July 2010 Dominic Mohan (Sun) General discussion July 2010 Colin Myler (News of the General discussion World) July 2010 Murdoch MacLennan General discussion (Telegraph Media Group) July 2010 Regional Broadcasters and Reception (No 10) Lobby July 2010 Tony Gallagher (Telegraph) Social July 2010 US Editors Overseas visit July 2010 Indian Editors Overseas visit August Tim Montgomerie General discussion 2010 (Conservative Home) August Rebekah Brooks (News Chequers 2010 International) September -

Various V NGN Judgment

Neutral Citation Number: [2016] EWHC 961 (Ch) Case No: Various IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE CHANCERY DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Rolls Building, Fetter Lane London EC4A 1NL Date: 28/04/2016 Before : MR JUSTICE MANN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : Various Claimants Claimants - and - News Group Newspapers Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Mr David Sherborne and Mr Julian Santos (instructed by Hamlins LLP) for the Claimants Mr Antony White QC, Mr Antony Hudson QC and Mr Ben Silverstone (instructed by Linklaters LLP) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 13th & 14th April 2016 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. ……………… MR JUSTICE MANN MR JUSTICE MANN Various v NGN Approved Judgment Mr Justice Mann : Introduction 1. These are two partially matching applications relating to some of the claims made against the defendant (NGN) alleging phone hacking and other unlawful activities in relation to several claimants, though the impact of the applications is capable of being felt in an unknown number of cases which might be launched in the future. Putting the matter shortly, the position is as follows. Like many other claimants before them, 4 claimants seek to make claims about such activities against NGN as proprietor of the former News of the World newspaper. There is no problem about that in these applications, though I have previously ruled on whether they are entitled to plead the full extent of wrongdoing that they sought to rely on. They also seek to make claims against the Sun newspaper, of which NGN is also the proprietor. -

Rt Hon Theresa May Mp (Home Secretary)

RT HON THERESA MAY MP (HOME SECRETARY) May 2010-July 2011 Meeting with proprietors, editors & senior media executives - This list sets out the Secretary of State’s meetings with senior media executives for the period May 2010 – July 2011. This includes all meetings with proprietors, senior executives and editors of media organisations for both newspapers and broadcast media. It does not include those meetings with journalists that ended up in interviews that appeared in the public domain, either in newspapers and magazines. It may also exclude some larger social events at which senior media executives may have been present. This is the fullest possible list assembled from the Secretary of State’s Parliamentary diary their departmental diary, personal diary and memory. Every effort has been taken to ensure that this is as accurate as possible but the nature of such an extensive exercise means something may have inadvertently got missed. Home Secretary Date of Meeting Name of Individual/s Purpose of Meeting May 2010 Asian Women of Presenting award Achievement Awards June 2010 Women of the Year Dinner Award ceremony and Awards (Glamour) June 2010 News International Social Summer Party June 2010 ITV Parliamentary Social Summer Reception July 2010 The Sun Police Bravery Presenting award Awards July 2010 Geordie Greig (Evening General discussion Standard) and others September 2010 Tony Gallagher (Daily General discussion Telegraph) and others September 2010 Dominic Mohan (The Sun) General discussion and one other September 2010 Matthew Cain -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 729 Friday No. 184 15 July 2011 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDER OF BUSINESS Coinage (Measurement) Bill Second Reading Live Music Bill [HL] Committee Rehabilitation of Offenders (Amendment) Bill [HL] Committee Media: News Corporation Motion to Take Note Written Answers For column numbers see back page £3·50 Lords wishing to be supplied with these Daily Reports should give notice to this effect to the Printed Paper Office. The bound volumes also will be sent to those Peers who similarly notify their wish to receive them. No proofs of Daily Reports are provided. Corrections for the bound volume which Lords wish to suggest to the report of their speeches should be clearly indicated in a copy of the Daily Report, which, with the column numbers concerned shown on the front cover, should be sent to the Editor of Debates, House of Lords, within 14 days of the date of the Daily Report. This issue of the Official Report is also available on the Internet at www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201011/ldhansrd/index/110715.html PRICES AND SUBSCRIPTION RATES DAILY PARTS Single copies: Commons, £5; Lords £3·50 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £865; Lords £525 WEEKLY HANSARD Single copies: Commons, £12; Lords £6 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £440; Lords £255 Index: Annual subscriptions: Commons, £125; Lords, £65. LORDS VOLUME INDEX obtainable on standing order only. Details available on request. BOUND VOLUMES OF DEBATES are issued periodically during the session. Single copies: Commons, £105; Lords, £40. Standing orders will be accepted. THE INDEX to each Bound Volume of House of Commons Debates is published separately at £9·00 and can be supplied to standing order. -

Minister Without Portfolio

MINISTER WITHOUT PORTFOLIO May 2010 – July 2011 Meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives This list sets out the Minister without Portfolio’s meetings with senior media executives for the period May 2010-July 2011. This includes all meetings with proprietors, senior executives and editors of media organisations for both newspapers and broadcast media. It does not include those meetings with journalists that ended up in interviews that appeared in the public domain, either in newspapers and magazines. It may also exclude some larger social events at which senior media executives may have been present. This is the fullest possible list assembled from the Minister without Portfolio’s diary and memory. Every effort has been taken to ensure that this is as accurate as possible but the nature of such an extensive exercise means something may have inadvertently got missed. Minister without Portfolio, The Rt Hon Baroness Warsi Date of Meeting Name of Organisation Purpose of Meeting May 2010 Sailesh Ram (Eastern Eye) General Discussion May 2010 Tony Litt (Sunrise Radio) General Discussion June 2010 Imdad Hussain Shezad (Star General Discussion News) July 2010 Pakistan Editors (during overseas Launch of Press Club visit) July 2010 Pakistan Editors (during overseas General Discussion visit) July 2010 Tony Litt (Sunrise Radio) General Discussion September 2010 Ahmed Versi (Muslim News) General Discussion October 2010 Michael Lyons (BBC Trust) Buffet Party Conference Luncheon October 2010 Guardian and Observer Drinks Party Conference -

What Rebekah Did…

SPECIAL REPORT PHONE-HACKING SCANDAL: TRIAL AND ERROR 1 THE PHONE-HACKING ScanDAL TRIAL AND ERROR A Special Report by Adam Macqueen TWO WEEKS AGO – just hours after the last issue of the Eye few days after news of her staff hacking Milly Dowler emerged, went to press – a jury of her peers found Rebekah Brooks not and the hiding of computer equipment and other material from guilty of all charges in her eight-month trial, while deciding that police searching her Cotswold and London homes. Andy Coulson knew all about the widespread phone-hacking at But during her 13 days in the witness box, Brooks did admit the News of the World during both their editorships. that several specific actions she had taken both as Sun editor As well as declaring that Brooks had no knowledge of her staff and chief executive of News International had been aimed at hacking phones or paying public officials on the Sun, the jury also preventing the full extent of the phone-hacking conspiracy at unanimously cleared her of charges of conspiracy to pervert the the News of the World from becoming public – even though, as course of justice regarding the removal of seven boxes marked as she insisted, she did not believe at the time that the claims she containing her notebooks from the News International archive a was trying to cover up were true. had discussed the Blunkett story with would plead guilty two months later. Coulson before it was published, she was Brooks told her colleagues that she WHAT REBEKAH “absolutely not” told about its provenance – believed there was not too much to worry but she certainly knew from 2006 onwards about: although police “do have GM’s phone that evidence existed of a more widespread records which show sequences of contacts DID… phone-hacking conspiracy at the News of the with News of the World before and after World, because the police told her about it. -

For Distribution to Cps MOD300002665

For Distribution to CPs Hospitality for Craig Oliver Date Organisation Hospitality 2011 16 March BBC Lunch 25 March Daily Mail/BBC Lunch 7 April The Times Lunch 18 April The Daily Mail Lunch 28 April The News of the World Lunch 9 May News International Lunch 17 May The Sun Dinner 26 May The Telegraph Lunch 27 May ITV Lunch 1 June CNN Lunch 6 June News International Lunch 9 June Independent/Herald Lunch 10 June LTA Ticket to Queens tennis 12 June Gates Foundation Lunch 16 June News International Summer Reception 27 June Financial Times Summer Reception 7 July Spectator Drinks 11 July Daily Mail Dinner ISJuly ITV Drinks 15July BBC Ticket(s) to the Proms 26 July The Times Lunch 27 July Channel 4 Lunch 2 August Total Politics/Portland Lunch 26 August Sky Lunch 15 September Carlton Club Dinner 17 October Sky Lunch 20 October Newspaper Society Lunch 24 October Cancer Research Lunch 1 November Channel 4 Lunch 8 November Mail on Sunday Lunch 8 November Evening Standard Drinks 10 November Guardian Lunch 11 November BBC Lunch 16 November Spectator Dinner 21 November BBC Dinner 22 November US Embassy Lunch 1 December Spectator Lunch 1 December Buckingham Palace Drinks 8 December Telegraph Lunch 12 December Sky Drinks MOD300002665 For Distribution to CPs 16 December Sun Military Awards Dinner 2012 31 January FT Lunch 2 February ITV Dinner 6 February Laureus Awards Dinner 7 February Daily Mail Lunch 21 February BBC Lunch 1 March Channel 5 Lunch 2 March BBC Lunch 6 March Telegraph Lunch 27 March Mail on Sunday Drinks 27 March PR W eek Drinks 30 March -

Page 01 June 27.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Thursday 27 June 2013 18 Shaaban 1434 - Volume 18 Number 5743 Price: QR2 The Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani has issued a decree stipulating that the official title of H H Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani will be H H the Father Emir. www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Emir outlines vision, mission The Emir H H DOHA: In his inaugural address to the nation as Emir, Sheikh Tamim H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad bin Hamad Al Al Thani, yesterday made it clear that his focus was on Thani announces the progress of the nation and a 20-member hinted at an extensive overhaul of various ministries. Cabinet. He said the restructuring of the ministries, a project that began last year, was necessary to avoid I ask him (H H duplication and overlapping of work and improve efficiency. Sheikh Hamad) The Emir later announced not to deny us a major Cabinet reshuffle and named the former minister of his opinion and state for interior affairs, H E advice when Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser bin Khalifa Al Thani, as Prime necessary: The Minister with additional charge Emir. of Interior Ministry. At least five new ministries including for youth affairs and sports, administrative develop- H E Sheikh ment, defence, and information Abdullah bin technology and communications have been created. Nasser bin Khalifa H E Dr Khalid bin Mohamed Al Al Thani named Attiyah has been named Foreign Minister, while a dozen new faces, Prime Minister and including a woman — H E Dr The Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani with the Prime Minister and Interior Minister H E Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser bin Khalifa Al Thani, and Interior Minister. -

The Tories and Murdoch Who Met Whom When

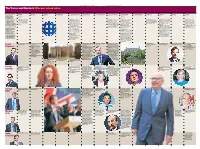

20 * The Guardian | Wednesday 27 July 2011 The Guardian | Wednesday 27 July 2011 * 21 The Tories and Murdoch Who met whom when The close relations between David May June July August September October November December January February March April May June Cameron’s inner circle and News 2010 2011 Corporation’s top 11 May Andy Coulson takes 1 September The New York 21 December Jeremy Hunt, 5 January It emerges that 3 March Hunt approves 5 April Edmondson, and the 23 June A former NoW executives have moved over as head of the new Times publishes claims by the culture secretary, is Ian Edmondson, a senior BSkyB’s proposal to hive off NoW chief reporter, Neville reporter, Terenia Taras, to the forefront of coalition government’s former News of the World given responsibility for NoW news editor, was Sky News from BSkyB, thus Thurlbeck, are arrested is arrested. Also arrested the phone-hacking media team after David reporter Sean Hoare that News International’s bid to suspended near the end of all but guaranteeing that he on suspicion of unlawfully on the same day is Laura scandal. This grid uses Cameron becomes prime Andy Coulson knew his staff buy the rest of BSkyB after 2010 after an internal inves- will approve the deal. intercepting voicemail Elston, a reporter for the information released minister. hacked phones; Coulson the business secretary, Vince tigation into hacking. messages. Press Association but it soon over the past 10 days denies the allegation. Cable, is secretly recorded 17 January Glenn Mulcaire 8 April News International emerges she is not involved to set out all declared 14 September Scotland Yard saying he had “declared says he was commissioned apologises to eight hacking in the affair and she is meetings between reopens its phone-hacking war” on Rupert Murdoch. -

Witness List Wc 09.01.12

Witness List Week Commencing 9 January 2012 Please note this list is subject to change and further witnesses may be added at short notice. Witnesses for each day are listed in alphabetical order. Monday 9th Tuesday 10th Wednesday 11th Thursday 12th Friday 13th January January January January January 10:00 – 16:30 10:00 – 16:30 10:00 – 16:30 10:00 – 16:30 Lionel Barber (FT) Liz Hartley Paul Ashford Non Duncan Larcombe (Associated (Northern & Shell) Sitting (The Sun) Newspapers) Chris Blackhurst Day Richard Desmond (Independent) Kelvin Mackenzie Peter Wright (Northern & Shell) (formerly with The (Associated Sun) Tony Gallagher Newspapers) Peter Hill (Telegraph) (Northern & Shell) Dominic Mohan (The Sun) William Dawn Neesom Lewis (formerly with (Northern & Shell) Gordon Smart (The the Telegraph) Sun) Nicole Patterson Murdoch MacLennan (Northern & Shell) (Telegraph) Justin Walford (The Robert Sanderson Sun) Manish Malhotra (Northern & Shell) (Independent) Andrew Mullins Hugh Whitlow (Independent) (Northern & Shell) Finbarr Ronayne (Telegraph) Stuart Higgins (The Benedict Brogan Kevin Beatty Martin Ellice Sun – to be read) (Telegraph – to be (Associated (Northern & Shell – read) Newspapers –to to be read) Simon Toms (The be read) Sun – to be read) Adam Cannon Gareth Morgan (Telegraph – to be James Welsh (Northern & Shell – David Yelland (The read) (Associated to be read) Sun – to be read) Newspapers – to Ian McGregor be read) Martin Townsend (Telegraph – to be (Northern & Shell – read) to be read) Peter Oborne (Telegraph – to be read) Arthur Wynn-Davies (Telegraph – to be read) Some witnesses will not give oral evidence. Instead, their statements will be 'read' into the Inquiry's proceedings. . -

Further Submission

Dear Sir/Madam In the previous phase of the CMA Inquiry we drew your attention to the developments in the claims against News Group Newspapers (NGN) in the managed phone hacking litigation (MTVIL). NGN is owned by News UK a subsidiary of News Corp which is controlled by the Murdoch Family Trust (MFT). There is no doubt that a cover-up of wrongdoing by News Corp would impact on the “genuine commitment” standard. We explained that not only were claimants alleging phone hacking at the news of the World but that the court was considering claims of voicemail interception and other unlawful information gathering at the Sun newspaper. We also explained that the court was considering extensive allegations pf concealment and destruction of evidence by senior executives at News International and that this included James Murdoch. We urged you to obtain the court papers relating to this litigation – in particular the pleadings which we believed had been entered and were thus available to third parties to access. There was no indication in your Phase 1 Report that you had even seen these papers let alone considered them. I have now obtained the pleadings in this litigation as they relate to the serious allegations against News International, James Murdoch, Rebekah Brooks and others. I attach them. They are (1) The Claimants’ (amended) Particulars of Concealment and Destruction (2) The (re-amended) Defence to the amended Particulars of Concealment and Destruction Inspection of these documents show them to be highly relevant to your inquiry, and to the relevant theory of harms therein.