Immigration Law : Issues for Faculty and Staff, 2007 Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

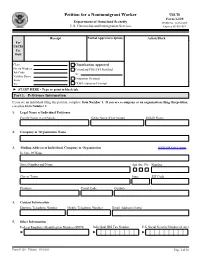

Form I-129, Petition for Nonimmigrant Worker

Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker USCIS Form I-129 Department of Homeland Security OMB No. 1615-0009 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Expires 09/30/2021 Receipt Partial Approval (explain) Action Block For USCIS Use Only Class: Classification Approved No. of Workers: Consulate/POE/PFI Notified Job Code: At: Validity Dates: From: Extension Granted To: COS/Extension Granted ► START HERE - Type or print in black ink. Part 1. Petitioner Information If you are an individual filing this petition, complete Item Number 1. If you are a company or an organization filing this petition, complete Item Number 2. 1. Legal Name of Individual Petitioner Family Name (Last Name) Given Name (First Name) Middle Name 2. Company or Organization Name 3. Mailing Address of Individual, Company or Organization (USPS ZIP Code Lookup) In Care Of Name Street Number and Name Apt. Ste. Flr. Number City or Town State ZIP Code Province Postal Code Country 4. Contact Information Daytime Telephone Number Mobile Telephone Number Email Address (if any) 5. Other Information Federal Employer Identification Number (FEIN) Individual IRS Tax Number U.S. Social Security Number (if any) ► ► ► Form I-129 Edition 03/10/21 Page 1 of 36 Part 2. Information About This Petition (See instructions for fee information) 1. Requested Nonimmigrant Classification (Write classification symbol): 2. Basis for Classification (select only one box): a. New employment. b. Continuation of previously approved employment without change with the same employer. c. Change in previously approved employment. d. New concurrent employment. e. Change of employer. f. Amended petition. 3. Provide the most recent petition/application receipt number for the ► beneficiary. -

GAO-18-608, NONIMMIGRANT VISAS: Outcomes of Applications And

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters August 2018 NONIMMIGRANT VISAS Outcomes of Applications and Changes in Response to 2017 Executive Actions GAO-18-608 August 2018 NONIMMIGRANT VISAS Outcomes of Applications and Changes in Response to 2017 Executive Actions Highlights of GAO-18-608, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Previous attempted and successful The total number of nonimmigrant visa (NIV) applications that Department of terrorist attacks against the United State (State) consular officers adjudicated annually peaked at about 13.4 million States have raised questions about the in fiscal year 2016, and decreased by about 880,000 adjudications in fiscal year security of the U.S. government’s 2017. NIV adjudications varied by visa group, country of nationality, and refusal process for adjudicating NIVs, which reason: are issued to foreign nationals, such as • tourists, business visitors, and Visa group. From fiscal years 2012 through 2017, about 80 percent of NIV students, seeking temporary admission adjudications were for tourists and business visitors. During this time, into the United States. For example, adjudications for temporary workers increased by about 50 percent and the December 2015 shootings in San decreased for students and exchange visitors by about 2 percent. Bernardino, California, led to concerns • Country of nationality. In fiscal year 2017, more than half of all NIV about NIV screening and vetting adjudications were for applicants of six countries of nationality: China (2.02 processes because one of the million, or 16 percent), Mexico (1.75 million, or 14 percent), India (1.28 attackers was admitted into the United million, or 10 percent), Brazil (670,000, or 5 percent), Colombia (460,000, or States under a NIV. -

Revised Residence Form -- Non-US Citizens

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Residence Status Supplemental Form for Non-U.S. Citizens If you are not a U.S. citizen, you must complete this supplemental form. Non-U.S. citizens must show that they have certain visa or immigration statuses in order to have the legal ability to maintain a domicile in North Carolina. Upon meeting these requirements, applicants who are non-U.S. citizens will be subjected to the same considerations as U.S. citizens in determining residence status for tuition purposes. If you are a dependent relying upon the domicile of your parent(s) or guardian(s) to establish residence for tuition purposes, this form should be completed by those parent(s) or guardian(s). Please complete this form in addition to the Residence and Tuition Status Application. The directions from the Residence and Tuition Status Application form are incorporated herein by reference. Please type all responses or print them clearly in ink. 1. Student’s full name: __________________________________________ PID: ___________________________ 2. Full name of Parent(s)/Guardian(s) (if applicable):__________________________________________________ 3. Do you (the student or parent/guardian, where applicable) possess a valid and current U.S. immigration status? Yes No If so, what is the designation of your current immigration status? _________________ (For example, provide the designation of your current visa or identify any pending immigration applications.) 4. When was your current immigration status (listed above) issued? (Month/Day/Year) ____/_____/____ When does your current immigration status expire? (Month/Day/Year)____/_____/____ 5. Please identify each and every immigration status, if any, that have been issued to you by the United States government and, where necessary, identify the specific types of visas by both letter and number (e.g., A-1, E- 2, G-4, H-1B, etc.) in the space provided. -

Temporary Migration to the United States

TEMPORARY MIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES NONIMMIGRANT ADMISSIONS UNDER U.S. IMMIGRATION LAW Temporary Migration to the United States: Nonimmigrant Admissions Under U.S. Immigration Law U.S. Immigration Report Series, Volume 2 About this Edition This document discusses nonimmigrants and the laws and regulations concerning their admission to the United States. The purpose of this report is to describe the various nonimmigrant categories and discuss the policy concerns surrounding these categories. Topics covered include: adjustment of status, temporary workers, work authorization, and visa overstays. The United States welcomes visitors to our country for a variety of purposes, such as tourism, education, cultural exchange, and temporary work. Admittance to the United States as a nonimmigrant is intended to be for temporary visits only. However, some nonimmigrants are permitted to change to a different nonimmigrant status or, in some cases, to permanent resident status. This report provides an overview of the reasons for visiting the United States on a temporary basis and the nexus between temporary visitor and permanent resident. Nonimmigrants – v. 06.a TEMPORARY MIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES: NONIMMIGRANT ADMISSIONS UNDER U.S. IMMIGRATION LAW Research and Evaluation Division U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Office of Policy and Strategy January 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by staff in the Research and Evaluation Division of the Office of Policy and Strategy, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, under the direction of David R. Howell, Deputy Chief, and Lisa S. Roney, Director of Evaluation and Research. The report was written by Rebecca S. Kraus. The following staff made significant contributions in the research for and review of this report: Lisa S. -

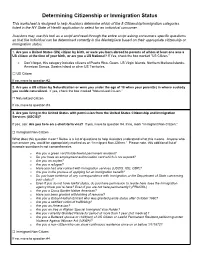

Determining Citizenship Or Immigration Status

Determining Citizenship or Immigration Status This worksheet is designed to help Assistors determine which of the 5 Citizenship/Immigration categories listed in the NY State of Health application to select for an individual consumer. Assistors may use this tool as a script and read through the entire script asking consumers specific questions so that the individual can be determined correctly in the Marketplace based on their appropriate citizenship or immigration status. 1. Are you a United States (US) citizen by birth, or were you born abroad to parents of whom at least one was a US citizen at the time of your birth, or are you a US National? If Yes, check the box marked “US Citizen.” • Don’t forget, this category includes citizens of Puerto Rico, Guam, US Virgin Islands, Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, Swains Island or other US Territories. ☐ US Citizen If no, move to question #2. 2. Are you a US citizen by Naturalization or were you under the age of 18 when your parent(s) in whose custody you reside naturalized. If yes, check the box marked “Naturalized Citizen.” ☐ Naturalized Citizen If no, move to question #3. 3. Are you living in the United States with permission from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)? If yes, ask: Are you here on a short-term visa? If yes, move to question #4. If no, mark “Immigrant Non-Citizen.” ☐ Immigrant Non-Citizen What does this question mean? Below is a list of questions to help Assistors understand what this means. Anyone who can answer yes, would be appropriately marked as an “Immigrant Non-Citizen.” Please note, this additional list of example questions is not comprehensive. -

Immigration and America's Future

Immigration and America’s Future: A NEW CHAPTER REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT TASK FORCE ON IMMIGRATION AND AMEriC A’S FUTURE C O-CHA ir S , S PENCE R A B R AHAM AND LEE H . H AM ilTON Doris Meissner Deborah W. Meyers Demetrios G. Papademetriou Michael Fix Immigration and America’s Future: A NEW CHAPTER Report of the Independent Task Force on Immigration and America’s Future Spencer Abraham and Lee H. Hamilton, Co-Chairs Doris Meissner Deborah W. Meyers Demetrios G. Papademetriou Michael Fix SEptEMBER 2006 © 2006 Migration Policy Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without prior permission, in writing, from the Migration Policy Institute. Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 0-9742819-3-X, 978-0-9742819-3-3 Cover and Design by Sally James of Cutting Edge Design, Inc. CONTENTS Foreword ...........................................................................................................................vii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................ix List of Task Force Members ..............................................................................................xi Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... xiii Preface .............................................................................................................................xxi -

Supporting Statement

Form I-129 Table of Changes January 28, 2010 OMB No. 1615-0009 LOCATION CURRENT PROPOSED Page 1 For USCIS Use Only For USCIS Use Only For USCIS Use Only Returned [text box] Delete all boxes to the left Date [text box] of the “Receipt” box: Date [text box] Resubmitted [text box] Date [text box] Receipt Date [text box] [reduce size of box to 3 x 2 Reloc Sent [text box] in– large enough to fit a Date [text box] barcode label] Date [text box] Reloc Rec’d [text box] Date [text box] Date [text box] □Petitioner Interviewed on_____ [text box] □Beneficiary Interviewed on___ [text box] _______________________ Class: ___________ Class: ___________ # of Workers: ___________ # of Workers: __________ Job Code: ___________ Priority Number:________ Validity Dates: ___________ Validity Dates: _______ From: ___________ From:______ To: ___________ To:_____ To Be Completed by Delete this entire section & Attorney or Representative, if enlarge the “Action Block” box any, to fit stamp size. □ Fill in box if G-28 is attached to represent the applicant. ATTY State License #: Page 1 Part 1. Information About the Part 1. Petitioner Information. Part 1. Petitioner Employer Filing This Petition Information About the Employer (If the employer is an individual, Filing This Petition (If the Information complete Number 1. employer is an individual, Organizations should complete complete Number 1; Number 2.) Organizations complete Number 2.) Please use the mailing 2. Company or Organization address of the petitioner. Name [text box] 1. Current Legal Name of Employer: 1 Telephone No. w/Area Code [text box] [text box: ( ) ] “C/O” line moved above line Mailing Address: (Street with “Mailing Address” and Number and Name) “Suite #”; Also “Zip/Postal [text box] Code” moved to same line as “City” & “State/Province” to Suite # allow for more space for “E-Mail [text box] Address”: C/O: (In Care Of) 2. -

How Do I Hire a Foreign National for Short-Term Employment in the United States?

I am an employer E1 How do I hire a foreign national for short-term employment in the United States? This customer guide covers a complex area of U.S. law and • H-1B1 – Specialty occupations for certain nationals of Singapore Government regulations. If in doubt, employers may wish to and Chile consult specialists in this area to ensure they proceed correctly. • H-2A – Temporary agricultural workers Employers sometimes need to hire foreign labor when there is • H-2B – Temporary workers performing other services or labor, a shortage of available U.S. workers to fill certain jobs. Under skilled or unskilled certain conditions, U.S. immigration law may allow a U.S. employer to file a Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker, with • H-3 – Trainees or special education exchange visitors U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) on behalf of a • I – Representatives of information media prospective foreign national employee. Upon approval of the petition, the prospective employee may apply for admission to the United • J-1 – Certain exchange visitors States, or for a change of nonimmigrant status while in the United • L-1A – Intra-company transferees (executives, managers) States, to temporarily work or to receive training. • L-1B – Intra-company transferees (employees with specialized For most employment-based nonimmigrant visa categories, the knowledge) employer starts the process by filing Form I-129 with USCIS. Filing instructions and forms are available on our Web site at www. • O-1 – Foreign nationals who have extraordinary ability in the uscis.gov. Please note that in some cases the employer must file sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics a Labor Condition Application or Application for Temporary • O-2 – Essential support personnel for O-1 Employment Certification with the Department of Labor (DOL) • P-1 – Internationally recognized athletes (or athletic team) or and/or obtain certain consultation reports from labor organizations members of an entertainment group and certain other athletes before filing a petition with USCIS. -

Long Brochure.Pdf

ILW.COM’S Immigration Law Library THE I-140 BOOK - Editor: Herbert A. Weiss THE IMMIGRATION COMPLIANCE BOOK - Editors: Angelo A. Paparelli, L. Batya Schwartz Ehrens, and Dan Siciliano THE CONSULAR POSTS BOOK - Editor: Rami Fakhoury US Tax Compliance For Immigrants And Employers: The Lawyer's Complete Guide Editor: Paula N. Singer, Esq. The Employer's Immigration Compliance Desk Reference - By: Gregory H. Siskind THE PERM BOOK - Editor: Joel Stewart THE H-1B BOOK - Editor: Karen Weinstock THE NURSE IMMIGRATION BOOK - Editors: Joseph P. Curran and Dan H. Berger THE REMOVAL BOOK - By Scott Bratton The Immigrant's Way - By Margaret W. Wong Immigration Practice 2009-2010 - Editors: Robert C. Divine and R. Blake Chisam Business Immigration Law: Strategies For Employing Foreign Nationals Editors: Rodney A. Malpert and Amanda Petersen Business Immigration Law: Forms and Filings - Authors: Rodney A. Malpert and Amanda Petersen The Whole ACT—INA by P. J. Patel 8 CFR Plus by P. J. Patel 20/22/28 CFR Plus by P. J. Patel Patel's Citations of Administrative Decisions under Immigration and Nationality Laws by P. J. Patel Publication Catalog THE I-140 BOOK Editor: Herbert A. Weiss Contributors: Brian S. Weiss, Kristen Quan Hammill, Prakash Khatri, Faye M. Kolly, Howard L. Kushner, Dorothee B. Mitchell, and Sherry Neal EDITOR Herbert A. Weiss is a partner at Garganigo, Goldsmith & Weiss, based in New York and has been serving the immigrant community for thirty five years. He has practiced immigration law since his admission to the bar. He has been a member of the firm since 1979. -

1819 Part V Resouce Guide Immigration

SF HIV FOG Open Enrollment Boot CAMP IV Resource Guide Part V Immigration Table of Contents Number of Pages Covered CA Immigration Fact Sheet 3 Immigration Status & The Marketplace 6 DHCS Employment Authorization Codes and Medi-Cal Benefits 8 Doc Typically Used by Lawfully Present Immigrants 14 Overview of Immigration Eligibility for Federal Programs 20 Getting the Health Care You Deserve Your immigration information is safe, secure and confidential It’s important to have health coverage to keep you and your family healthy Covered California is a place where you can compare and get health insurance plans, and get financial assistance to pay for your health coverage if you qualify. When you apply through Covered California, you can also determine if you are eligible for reduced premiums or Medi-Cal. Most California residents who are U.S. citizens, U.S. nationals, or who are “lawfully present” can get health insurance with financial help through Covered California. Individuals with other immigration statuses may be eligible for health coverage through Medi-Cal, although the benefits may be limited. If you are applying for health coverage for yourself or your family members, know that all of your information is safe and confidential. Covered California, in partnership with the National Immigration Law Center, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials Educational Fund, Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Los Angeles, the California Immigrant Policy Center and the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles is encouraging everyone to apply for health coverage, without fear that their application will affect their immigration status or the status of their family members. -

Regulatory Impact Analysis

Regulatory Impact Analysis U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Fee Schedule and Changes to Certain Other Immigration Benefit Request Requirements Final Rule (8 CFR Parts 103, 106, 204, 211, 212, 214, 216, 223, 235, 236, 240, 244, 245, 245a, 248, 264, 274a, 301, 319, 320, 322, 334, 341, 343a, 343b, and 392) RIN: 1615-AC18 CIS No. 2627-18; DHS Docket No.: USCIS-2019-0010 July 22, 2020 1 AILA Doc. No. 20073100. (Posted 8/4/20) TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Executive Order 12866 (Regulatory Planning and Review) and Executive Order 13563 (Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review), and Executive Order 13771 (Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs) .. 3 1. Changes to Provisions and Impacts .............................................................................................................. 25 a. Reduced Fees for Filing Online ...................................................................................................................... 27 b. Secure Mail Initiative ..................................................................................................................................... 34 c. Clarify Dishonored Fee Check Re-presentment Requirement, Fee Payment Method, and Non-refundability ....................................................................................................................................................................... 37 d. Eliminate $30 Returned Check Fee ............................................................................................................... -

Immigration Legislation and Issues in the 108Th Congress

Order Code RL32169 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Immigration Legislation and Issues in the 108th Congress Updated October 6, 2004 name redacted, Coordinator, name redacted, name redacted, name redacted Domestic Social Policy Division name redacted, Stephen R. Viña American Law Division Charlotte Stichter Office of Legislative Information Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Immigration Legislation and Issues in the 108th Congress Summary The 108th Congress has considered and is considering legislation on a wide range of immigration issues. Chief among these are the immigration-related recommendations of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (also known as the 9/11 Commission), expedited naturalization through military service, and foreign temporary workers and business personnel. Several major bills that seek to implement recommendations of the 9/11 Commission propose significant revisions to U.S. immigration law: H.R. 10, S. 2845, S. 2774/H.R. 5040, and H.R. 5024. Of these bills, H.R. 10 proposes the most extensive revisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). The major immigration areas under consideration in these comprehensive 9/11 Commission bills include: asylum, biometric tracking systems, border security, document security, exclusion, and visa issuances. The 108th Congress has enacted a measure on expedited naturalization through military service. P.L. 108-136, the FY2004 Defense Department Authorization bill, amends military naturalization and posthumous citizenship statutes and provides immigration benefits for immediate relatives of U.S. citizen servicemembers who die as a result of actual combat service. In the area of foreign temporary workers and business personnel, the 108th Congress has enacted legislation to implement the Chile (P.L.