Temporary Migration to the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clarification of Nonimmigrant Visa Status

WGIUPD GENERAL INFORMATION SYSTEM 02/10/04 DIVISION: Office of Medicaid Management PAGE 1 GIS 04 MA/002 TO: Local District Commissioners, Medicaid Directors FROM: Kathryn Kuhmerker, Deputy Commissioner Office of Medicaid Management SUBJECT: Clarification of Nonimmigrant Visa Status EFFECTIVE DATE: Immediately CONTACT PERSON: Local District Support Unit Upstate (518) 474-8216 NYC (212) 268-6855 The purpose of this GIS message is to clarify nonimmigrant visa status. This GIS message supersedes GIS 03 MA/005 issued 02/24/03. As explained below, nonimmigrants who hold a K, S, U or V visa are to be considered as “permanently residing in the United States under color of law” (PRUCOL) and, if otherwise eligible, may receive Medicaid, Family Health Plus (FHPlus) and Child Health Plus A (CHPlus A). However, holders of other nonimmigrant visas that are issued to persons in the United States on a temporary basis only are eligible for Medicaid only for the treatment of an emergency medical condition. There have been several new visa categories issued by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) [formerly the Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) and the Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services (BCIS)] over the past several years. Some categories of nonimmigrant status allow the status (visa) holder to work and eventually adjust to Lawful Permanent Residence (LPR). These categories allow the individual to apply for adjustment to LPR status after he or she has had the nonimmigrant status for a period of time. Such statuses include, for example: K status: For the spouse, child, or fiancé (e) of a U.S. -

IMMIGRATION LAW BASICS How Does the United States Immigration System Work?

IMMIGRATION LAW BASICS How does the United States immigration system work? Multiple agencies are responsible for the execution of immigration laws. o The Immigration and Naturalization Service (“INS”) was abolished in 2003. o Department of Homeland Security . USCIS . CBP . ICE . Attorney General’s role o Department of Justice . EOIR . Attorney General’s role o Department of State . Consulates . Secretary of State’s role o Department of Labor . Employment‐related immigration Our laws, while historically pro‐immigration, have become increasingly restrictive and punitive with respect to noncitizens – even those with lawful status. ‐ Pro‐immigration history of our country o First 100 Years: 1776‐1875 ‐ Open door policy. o Act to Encourage Immigration of 1864 ‐ Made employment contracts binding in an effort to recruit foreign labor to work in factories during the Civil War. As some states sought to restrict immigration, the Supreme Court declared state laws regulating immigration unconstitutional. ‐ Some early immigration restrictions included: o Act of March 3, 1875: excluded convicts and prostitutes o Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882: excluded persons from China (repealed in 1943) o Immigration Act of 1891: Established the Bureau of Immigration. Provided for medical and general inspection, and excluded people based on contagious diseases, crimes involving moral turpitude and status as a pauper or polygamist ‐ More big changes to the laws in the early to mid 20th century: o 1903 Amendments: excluded epileptics, insane persons, professional beggars, and anarchists. o Immigration Act of 1907: excluded feeble minded persons, unaccompanied children, people with TB, mental or physical defect that might affect their ability to earn a living. -

TN Professionals from Canada and Mexico

5000 Forbes Ave, Posner Hall 1st Floor, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Phone: (412) 268-5231 ▪ Email: [email protected] ▪ Web: www.cmu.edu/oie TN Professionals from Canada and Mexico I. Explanation and terms The TN (Trade NAFTA) category resulted from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to facilitate the entry of Canadian and Mexican citizens to work in the US in certain professions on a temporary basis. For a list of the TN occupations, visit: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/employment/visas-canadian-mexican-nafta-professional- workers.html II. Conditions and limitations An advantage of TN status is that there is no upper limit on the length of time that an individual may remain working in TN status, and as of January 1, 2004, there is no numerical limit on the number of new Canadian or Mexican TN applications. For Canadians, TN status is quick to obtain at the border or port of entry. Disadvantages of the TN include (1) it is only valid for a limited number of occupations, (2) TN status is only available to citizens of Canada or Mexico, and (3) since it is meant to be temporary, tenure-track or tenured professors may have difficulty in obtaining TN status. Canadians do not require a visa stamp, but must renew every three years. For Mexicans, a TN worker must have a TN visa from a US consulate to enter the US. TN’s are admitted to the US for three year increments, and must renew every three years. TN status is “employer specific.” A person in TN status who wants to change employers must make a new application – at the border or via the US Immigration and Citizenship Services (USCIS) for Mexicans – before starting new employment in order to obtain a new, properly notated I-94 card. -

AUM International Student Handbook

International Student Handbook *Although the content of this handbook represents the most current information at the time of publication, changes may be made with respect to the information contained herein without prior notice. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 4 WELCOME 5 OFFICE OF GLOBAL INITIATIVES 6 ABOUT AUBURN UNIVERSITY AT MONTGOMERY 7 WARHAWK TRADITIONS 7 PREPARING FOR TRAVEL 8 HOW TO GET YOUR VISA 8 ARRIVAL DATE 9 ARRIVAL AT A U.S. PORT OF ENTRY 9 WHAT TO BRING TO THE USA 10 AIRPORT PICKUP SERVICE 11 PREPARING FOR ARRIVAL 11 AUM EMAIL ACCOUNT 11 LIKE US ON FACEBOOK 12 MY.AUM.EDU 12 ESTIMATED COST OF TUITION AND FEES 12 INTERNATIONAL STUDENT SCHOLARSHIP 13 HOUSING 14 NEW STUDENT CHECKLIST 17 ARRIVAL 18 ARRIVAL AND ORIENTATION 18 HEALTH INSURANCE 18 VACCINATIONS 19 ACADEMIC ADVISING 19 INTERNATIONAL TRANSFER CREDITS 19 AUM STUDENT IDENTIFICATION CARD (WARHAWK CARD) 22 HOW TO PAY TUITION AND FEES 22 PAYMENT PLANS 22 ARRIVAL CHECKLIST 23 IMMIGRATION MATTERS 24 F-1 VISA STATUS 24 J-1 VISA STATUS 24 DO'S AND DON'TS (ASK BEFORE YOU ACT) 25 REDUCED COURSE LOAD 25 ONLINE COURSES 26 2 TRANSIENT ENROLLMENT AT ANOTHER INSTITUTION 27 EMPLOYMENT (ON-CAMPUS WORK VS. OFF-CAMPUS WORK) 27 OPTIONAL PRACTICAL TRAINING (OPT) 28 24-MONTH STEM OPTIONAL PRACTICAL TRAINING EXTENSION 29 CURRICULAR PRACTICAL TRAINING (CPT) 30 SOCIAL SECURITY NUMBER 30 TAXES 30 TRAVEL 32 CHANGE OF ADDRESS 32 CHANGE OF MAJOR 32 PROGRAM EXTENSION / RENEWING YOUR I-20 32 RENEWING YOUR VISA 33 ACADEMIC LIFE 33 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 33 CLASS SCHEDULE 33 DEGREE REQUIREMENTS -

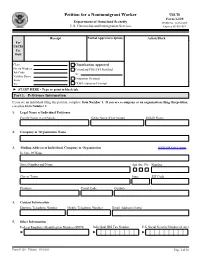

Form I-129, Petition for Nonimmigrant Worker

Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker USCIS Form I-129 Department of Homeland Security OMB No. 1615-0009 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Expires 09/30/2021 Receipt Partial Approval (explain) Action Block For USCIS Use Only Class: Classification Approved No. of Workers: Consulate/POE/PFI Notified Job Code: At: Validity Dates: From: Extension Granted To: COS/Extension Granted ► START HERE - Type or print in black ink. Part 1. Petitioner Information If you are an individual filing this petition, complete Item Number 1. If you are a company or an organization filing this petition, complete Item Number 2. 1. Legal Name of Individual Petitioner Family Name (Last Name) Given Name (First Name) Middle Name 2. Company or Organization Name 3. Mailing Address of Individual, Company or Organization (USPS ZIP Code Lookup) In Care Of Name Street Number and Name Apt. Ste. Flr. Number City or Town State ZIP Code Province Postal Code Country 4. Contact Information Daytime Telephone Number Mobile Telephone Number Email Address (if any) 5. Other Information Federal Employer Identification Number (FEIN) Individual IRS Tax Number U.S. Social Security Number (if any) ► ► ► Form I-129 Edition 03/10/21 Page 1 of 36 Part 2. Information About This Petition (See instructions for fee information) 1. Requested Nonimmigrant Classification (Write classification symbol): 2. Basis for Classification (select only one box): a. New employment. b. Continuation of previously approved employment without change with the same employer. c. Change in previously approved employment. d. New concurrent employment. e. Change of employer. f. Amended petition. 3. Provide the most recent petition/application receipt number for the ► beneficiary. -

Government of the Republic of Lithuania

Official translation 5 September 2014 GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA RESOLUTION No 79 22 January 2014 ON THE APPROVAL OF THE LITHUANIAN MIGRATION POLICY GUIDELINES Vilnius Acting pursuant to Paragraph 346 of the Priority Measures for Implementation of the Government Programme for 2012-2016, approved by Resolution No 228 of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania of 13 March 2013 on Approval of Priority Measures for Implementation of the Government Programme for 2012-2016, and with a view to establishing the objectives, principles and areas of the Lithuanian migration policy, as well as to ensuring proper management of migration processes, the Government of the Republic of Lithuanian has resolved: 1. To approve the Lithuanian Migration Policy Guidelines (as appended). 2. To establish that the provisions of the Lithuanian Immigration Policy Guidelines (hereinafter referred to as the Guidelines) approved by the present Resolution shall be followed by ministries, Government institutions, institutions under the ministries, other national authorities and institutions accountable to the Government of the Republic of Lithuania, as they make decisions falling within their respective competencies, draft legislation, consider proposals regarding the adoption of European Union legal acts, as well as draw up negotiation lines of the Republic of Lithuania on these proposals. 3. To recommend to municipalities and other national institutions and agencies, which are outside of the subordination of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania, that they follow the provisions of the Guidelines. 4. To repeal: 4.1. Resolution No 957 of 24 September 2008 of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania on Approval of the Description of Monitoring, Analysis and Forecasting Procedures for Economic Migration Processes and the State of Lithuanians Living Abroad, with all its amendments; 4.2. -

SECTION FIVE Canadian TN Nonimmigrant Pursuant to NAFTA

SECTION FIVE Canadian TN Nonimmigrant pursuant To NAFTA 8 CFR 214.6 - TN Professionals 123 Requirements for admission 134 Extension of Stay 138 Change of/or additional employer 138 Spouse and children 139 Denial of "TN" application for admission 139 TN Processing Summary 140 TN Information Handout 141 HQINS: NOVEMBER 1999 122 8 CFR Sec. 214.6 Canadian and Mexican citizens seeking temporary entry to engage in business activities at a professional level. (Sec. 214.6 revised 1/1/94; 58 FR 69212) (a) General. Under Section 214(e) of the Act, a citizen of Canada or Mexico who seeks temporary entry as a business person to engage in business activities at a professional level may be admitted to the United States in accordance with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). (b) Definitions. As used in this section, the terms: Business activities at a professional level means those undertakings which require that, for successful completion, the individual has a least a baccalaureate degree or appropriate credentials demonstrating status as a professional in a profession set forth in Appendix 1603.D.1 of the NAFTA. Business person, as defined in the NAFTA, means a citizen of Canada or Mexico who is engaged in the trade of goods, the provision of services, or the conduct of investment activities. Engage in business activities at a professional level means the performance of prearranged business activities for a United States entity, including an individual. It does not authorize the establishment of a business or practice in the United States in which the professional will be, in substance, self-employed. -

New York State DREAM Act Application

Step-by-Step User Guide to completing the New York State DREAM Act Application This user guide breaks down the New York State DREAM Act eligibility application and clarifies why certain questions are asked, how to answer each question accurately, and what documentation must be provided to verify your eligibility. Table of Contents Overview of Applications ........................................................................................................................... 3 The New York State DREAM Act Eligibility Requirements .............................................................. 3 NYS DREAM Act Application ................................................................................................................... 5 Student High School Education Details .............................................................................................. 5 High School Status ............................................................................................................................. 5 High School Completion .................................................................................................................... 7 Student Citizenship and Immigration Status ...................................................................................... 8 Social Security Number (SSN) or Taxpayer Identification Number (TIN): .............................. 10 Student Information .............................................................................................................................. 10 Student -

Vivir En El Norte Lectura.Pdf

1 2 Rodolfo Cruz Piñeiro Rogelio Zapata-Garibay (coordinadores) 3 4 Rodolfo Cruz Piñeiro Rogelio Zapata-Garibay (coordinadores) 5 ¡Vivir en el norte! : condiciones de vida de los mexicanos en Chicago / Rodolfo Cruz Piñeiro, Rogelio Zapata-Garibay, coordinadores. – Tijuana : El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, 2013. 322 pp. ; 14 x 21.5 cm ISBN: 978-607-479-115-0 1. Mexicanos – Illinois – Chicago. 2. México – Emigración e inmigración. 3. Estados Unidos – Emigración e inmigración. I. Cruz Piñeiro, Rodolfo. II. Zapata-Garibay, Rogelio. III. Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Tijuana, Baja California). F 550 .M4 V5 2013 Primera edición, 2013 D. R. © 2013, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, A. C. Carretera escénica Tijuana-Ensenada km 18.5 San Antonio del Mar, 22560, Tijuana, B. C., México www.colef.mx ISBN: 978-607-479-115-0 Coordinación editorial: Óscar Manuel Tienda Reyes Corrección y diseño editorial: Franco Félix Última lectura: Luis Miguel Villa Aguirre Fotografía de portada: Ali Ertürk Impreso en México / Printed in Mexico 6 ÍNDICE Introducción. ¡Vivir en el norte! Compleja realidad de los mexicanos en Chicago Rogelio Zapata-Garibay ..……………….........……...…… 9 Presencia mexicana en Chicago: Breve revisión historiográfica Rogelio Zapata-Garibay .……..……….................….…... 43 Características sociodemográficas de los mexicanos residentes en Chicago Rogelio Zapata-Garibay / Jesús Eduardo González-Fagoaga / Rodolfo Cruz Piñeiro ................……. 71 Trabajadores de origen mexicano en la zona metropolitana de Chicago Maritza Caicedo Riascos ....……...................................... 101 7 Aspectos de la salud de los mexicanos en Chicago Rogelio Zapata-Garibay /Jesús Eduardo González-Fagoaga / María Gudelia Rangel Gómez / Grecia Carolina Gallardo Torres ……...……….. 135 La construcción de la doble pertenencia de los mexicanos en Chicago Marlene Celia Solís Pérez / Guillermo Alonso Meneses / Rogelio Zapata-Garibay ...….......................................... -

Immigration Manual

Immigration Manual November 2006 Baker & McKenzie International is a Swiss Verein with member law firms around the world. In accordance with the common terminology used in professional service organizations, reference to a “partner” means a person who is a partner, or equivalent, in such a law firm. Similarly, reference to an “office” means an office of any such law firm. © 2006 Baker & McKenzie All rights reserved. This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study or research permitted under applicable copyright legislation, no part may be reproduced or transmitted by any process or means without prior written permission. IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER. The material in this booklet is of the nature of general comment only. It is not offered as advice on any particular matter and should not be taken as such. The firm and the contributing authors expressly disclaim all liability to any person in respect of anything and in respect of the consequences of anything done or omitted to be done wholly or partly in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this booklet. No client or other reader should act or refrain from acting on the basis of any matter contained in it without taking specific professional advice on the particular facts and circumstances in issue. Immigration Manual Immigration Manual INTRODUCTION This manual is designed to provide a general overview of the immigration laws and procedures of various countries. Please note that the immigration laws and procedures are constantly changing and are subject to new policies and developments. Therefore, this manual is not intended to be exhaustive and specific questions should be directed to the Executive Transfer and Immigration Department of Baker & McKenzie, Hong Kong. -

Background Essay—The History of Immigration Law in the United States

HANDOUT A Background Essay—The History of Immigration Law in the United States Read the background essay and answer the critical thinking questions at the Directions: end. In addition, formulate your own questions about the content discussed. In the modern era, nation-states are defined as Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution much by their borders as by their unique laws, empowers the Congress to “Establish a forms of government, and distinct national Uniform Rule of Naturalization.” The first cultures. Since the early years of the United national law concerning immigration was the States’ history, the federal government has Naturalization Act of 1790, which stated that sought, with varying degrees of success, to limit any free white person who had resided in the and define the nature and scale of immigration U.S. for at least two years could apply for full into the country. In the first seventy years of the citizenship. Congress also required applicants nation’s history, immigration was left largely to demonstrate “good character” and swear an unchecked; Congress focused its attention oath to uphold the Constitution. Blacks were on defining the terms by which immigrants ineligible for citizenship. could gain the full legal rights of citizenship. In 1795, naturalization standards were Beginning in the 1880s, however, Congress began changed to require five years’ prior residence in to legislate on the national and ethnic makeup of the U.S., and again in 1798 to require 14 years’ immigrants. Lawmakers passed laws forbidding residence. The 1798 revision was passed amidst certain groups from entering the country, and the anti-French fervor of the Quasi-War and restricted the number of people who could enter sought to limit the influence of foreign-born from particular nations. -

Fiscal Year 2019 Entry/Exit Overstay Report March 30, 2020

Fiscal Year 2019 Entry/Exit Overstay Report March 30, 2020 i Message from the Acting Secretary I am pleased to present the following “Fiscal Year 2019 Entry/Exit Overstay Report” prepared by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Pursuant to the requirements contained in Section 2(a) of the Immigration and Naturalization Service Data Management Improvement Act of 2000 (Pub. L. No. 106-215), Fiscal Year 2020 Appropriations Act (Pub. L. No. 116-93), and House Report 116-125, DHS is submitting this report on overstay data. DHS has generated this report to provide data on departures and overstays, by country, for foreign visitors to the United States who were expected to depart in Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 (October 1, 2018 - September 30, 2019). DHS is working with the U.S. Department of State (DOS) to share information on departures and overstays, especially as it pertains to the visa application and adjudication process, with the goals of increasing visa compliance and decreasing overstay numbers and rates. This report is being provided to the following Members of Congress: The Honorable Lindsey Graham Chairman, Senate Committee on Judiciary The Honorable Dianne Feinstein Ranking Member, Senate Committee on Judiciary The Honorable Jerrold Nadler Chairman, House Committee on Judiciary The Honorable Doug Collins Ranking Member, House Committee on Judiciary The Honorable Nita M. Lowey Chairwoman, House Appropriations Committee The Honorable Kay Granger Ranking Member, House Appropriations Committee The Honorable Richard Shelby Chairman, Senate Appropriations Committee The Honorable Patrick Leahy Ranking Member, Senate Appropriations Committee The Honorable Bennie Thompson Chairman, House Committee on Homeland Security ii The Honorable Mike Rogers Ranking Member, House Committee on Homeland Security The Honorable Ron Johnson Chairman, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs The Honorable Gary C.