How Rich Countries Became Rich and Why Poor Countries Remain Poor: It’S the Economic Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federico Giovanni

The Americas Divergence. Independence versus Emancipation in Latin America and the Caribbean 1820-1870 Giovanni Federico1 Antonio Tena-Junguito2 Abstract The Debate on the historical origins of the American divergence insists in the relevance of the half century following Iberian Independence. Wars, disorder and political instability that occurred in the postcolonial period have been linked to the failures of Iberian colonial institutions rooted in the colonial legacy. This article claims, contrary to conventional wisdom, that post-colonial performance in Latin America did not help to explain the Great Divergence of the Americas. In one hand, there is not any solid quantitative evidence that support that historical narrative with a few exceptions (notably Mexico). On the other hand, new evidence on Export performance of a wide variety of polity units would be reluctant to such a pessimistic view as that of the “lost decades”. Emancipation in the British and French colonies produce a real collapse of those tropical colonial exports but an opportunity for the Iberian tropics (notably Brazil and Cuba, the South of the US, but also Central America). This positive economic dynamism of the Iberian tropics sum to others good performance, as those of Argentine, Chile or Peru, to offer a different picture of the American divergence in the early globalization years. Introduction The Mexican president, Porfirio Diaz, said once 'Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to the United States'. In economic history, this statement holds true for the whole continent south of the Rio Grande. If compared with the United States, the economic performance of Latin America appears apparently very poor in the first decades of the 19th century (the 'lost decades') and mediocre at best throughout the whole century. -

Leader Board STANDINGS 2016 Leaderboard P Gross Skins # P Net

Leader Board STANDINGS 2016 Top 14 of Leader Board qualified for the Barney Cup vs Elmridge Top 5 in Gross and Net skins qualified for Season Ending Skins LeaderBoard P Gross Skins # P Net Skins # P 1 Jim Chiaradio 1418 Austin Cilley 27 480 Jim Chiaradio 11 306 2 Austin Cilley 1232 Jim Chiaradio 19 425 Lou Laudone 7 227 3 Chuck Falcone 1032 Karl Saila 17 273 Pete DiMaggio 11 223 4 Andy MacMahon 898 Andy McMahon 14 260 Chris Jurgasik 9 189 5 Chris Jurgasik 828 Glen Blackburn 11 235 Joe Luzzi Sr. 4 182 6 Tony Chiaradio 791 Chuck Falcone 8 192 Duke Ellington 7 179 7 Jim Murano 758 Mike Bliven 7 191 Ron Nye 7 179 8 Joe Luzzi Sr. 705 Jody Vacca 7 174 Chuck Falcone 7 175 9 John Donohue 692 Lou Laudone 8 156 Pete Chiaradio 7 171 10 Pete Chiaradio 676 John Donohue 11 154 Dave Morrone 7 168 11 Lou Laudone 653 Jack Donohue 4 132 Randy Dwight 4 165 12 Steve Ruzzo 621 Kyle James 7 102 Joe Woycik 6 161 13 Bob Gebler 613 Pete Chiaradio 5 95 Tom Hogan 6 152 14 Dave Morrone 608 Ray Barry 6 92 Randy Orlomoski 5 150 15 Mike Bliven 551 Joe Woycik 6 83 Bill Mathurin 5 127 16 Karl Saila 453 Jim Burbine 6 74 Mike Bliven 6 120 17 Joe Woycik 441 Joe Luzzi Sr. 4 63 Bob Gebler 5 119 18 Tom Hogan 436 Bob Gebler 4 59 Ed Morenzoni SR 3 116 19 Glen Blackburn 411 Lou Toscano 4 59 Vin Urso 2 115 20 Jim Burbine 405 Chris Jurgasik 5 57 Leo Larviere 4 110 21 Duke Ellington 377 John Doherty 1 45 Mike Classey 5 102 22 Lou Toscano 370 Bill Mathurin 2 43 Tony Chiaradio 4 100 23 Bill Mathurin 365 Charlie Toscano 2 28 John Sullivan 4 90 24 Jody Vacca 356 Randy Orlomoski 2 27 Charlie Toscano 4 88 25 John Sullivan 330 Joe Celico 2 25 Jack Donohue 2 82 26 Jack Donohue 324 Pete DiMaggio 2 24 Dave Crawn 3 75 27 Kyle James 322 Duke Ellington 1 18 Joe Luzzi Jr. -

TITLE Stella Mccartney: Responsibility's on the Agenda

TITLE Stella McCartney: responsibility's on the agenda INTRO She is one of the most successful fashion designers of our time and the woman behind the world's first vegetarian luxury fashion brand. But the road to the top has been tough. Stella McCartney talks to Anna Blom about panic attacks and the 'rich daddy's girl' label, and her own hard slog to get the fashion industry to become sustainable and modern. COPY How can you become one of the world's most successful fashion designers without using real leather? Stella McCartney, founder of the fashion house of the same name and daughter of ex-Beatle Sir Paul McCartney, has done just that. Famous for her feminine silhouettes and masculine-inspired garments, her fashion emporium is worth billions. Her 'Falabella' bag from 2010 is an icon, despite the fact that it is made using 'eco alter nappa', a mixture of recycled polyester and vegetable oils. Ever since her graduation show from Central Saint Martins in London in 1995, she has refused to use real leather, furs or feathers. She has been vegetarian since childhood, and when she was growing up her father Paul used to challenge her and her siblings to come up with an alternative to meat for the family's dinner. Her late mother Linda McCartney even launched a successful series of frozen vegetarian food in the UK, long before today's veggie trend. This consideration for people, animals and nature has followed Stella McCartney throughout her life. "For me, vegetarianism is based on ethics. My mum was very vocal and we were all educated to understand why we weren't eating meat. -

MIDWEEK RESULTS - Skins Game

MIDWEEK RESULTS - Skins game. December '14 Team #1 $ Team #2 $ Massingill, Harry D $48 Bradley, Gary $30 Espinosa, William $30 Rodriguez, Jose M $12 Ashen, Chuck H $30 Fairhurst, Neil B $24 Rodriguez, Don 0 Ahders, Bob $42 8:00 AM 8:08 AM Team #3 $ Team #4 $ Yurong, Willam $25.50 Deacon, Peter $90 Spreitzer, Gene $13.50 Guinn, Gary 0 Hart, Jeff $55.50 Kemp, Vern $12 Berg, Don $13.50 Siler, Roger R $6 Time: 08:16 am Time: 08:24 am Team #5 $ Team #6 $ Dopkins, Steve C 0 Hodges, Gary R $6 Jones, Chris David $72 Whitaker, Bill $24 Nygard, Kevin L $18 Chase, Jerry M $60 Watts, David A $18 McIntyre, Stuart $18 Time: 08:32 am Time: 08:40 am Team #7 $ Team #8 $ Reid, Robert A $48 Bottel, Rod $48 Auble, James $36 Reed, Alan E $30 Hoffman, Ms. Jan $12 Chow, Weldon $0 Gauthreaux, Sidney J $12 Baynes, Keith C. $30 Time: 08:48 am Time: 08:56 am Team #9 $ Team #10 $ Rousseve, Greg $9 Stein, Greg $36 Pintar, Donn $45 Bradford, Jeff 0 Landis, Steven $15 Smiley, George $18 Clark, Andrew J $39 Welborn, Roger $54 Time: 09:04 am Time: 09:12 am Team #11 $ Team #12 $ Kaczor, John D $6 Currier, Edwin J $6 Steyn, Gerard $60 Deccico, Jim $21 Henry, Ken W $24 Fleischer, Rich $63 Landsittel, Donald $18 Dixon, Robert $18 Time: 09:20 am Time: 09:28 am Team #13 $ Tee Team #14 $ Seymour, Ralph V $12 Dileo, Marty 0 Myas, Brandt R. $18 Jurach, Jerry P $30 Vona, Joe $30 Oneil, Dennis $36 Fasciola, Joe $48 Humphrey, Jack $42 Time: 09:36 am Time: 09:44 am Team #15 $ Team #16 $ Steed, Don $36 Beach, George W $9 Foster, Randy $30 Olson, Doug $21 1 MIDWEEK RESULTS - Skins game. -

GLO DP 0038.Pdf

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Belke, Ansgar; Domnick, Clemens; Gros, Daniel Working Paper Business Cycle Synchronization in the EMU: Core vs. Periphery GLO Discussion Paper, No. 38 Provided in Cooperation with: Global Labor Organization (GLO) Suggested Citation: Belke, Ansgar; Domnick, Clemens; Gros, Daniel (2017) : Business Cycle Synchronization in the EMU: Core vs. Periphery, GLO Discussion Paper, No. 38, Global Labor Organization (GLO), Maastricht This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/156158 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Business Cycle Synchronization in the EMU: Core vs. Periphery∗ Ansgar Belkey Clemens Domnickz Daniel Gros§ Abstract This paper examines business cycle synchronization in the European Monetary Union with a special focus on the core-periphery pattern in the aftermath of the crisis. -

User Manual Version 1.1 June 2019

USER MANUAL VERSION 1.1 JUNE 2019 SLAYER STEAM LP USER MANUAL V1.1 | JUNE 2019 1 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Copyright © 2018, 2016 by Seattle Espresso Machine Corporation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, Seattle Espresso Machine Corporation distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior 6133 6th Avenue South written permission of the publisher, except in the case of noncommercial Seattle, Washington, USA 98108 uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, contact the SLAYERESPRESSO.COM publisher. TERMS & CONDITIONS Slayer makes no representations or warranties with respect to the contents of this publication. Information contained herein is subject to change without notice. Every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this manual; nevertheless, Slayer assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions or any damages resulting from the use of this information. Read this manual completely before installing and operating your Slayer espresso machine. Incorrect installation and operation may result in damage to the equipment, personal injury, or even death. Disregarding the instructions contained herein indemnifies Slayer from all resulting damages and may void the equipment warranty. For additional safety precautions, see the safety advisory on page 7. SLAYER STEAM LP USER MANUAL V1.1 | JUNE 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Slayer Steam LP 1 Prepare Espresso 29 Copyright Information 2 Steam Milk 30 Table of Contents 3 Machine Calibrations 31 Welcome 4 Advanced Menu 33 Resources -

2019-2020 Missouri Roster

The Missouri Roster 2019–2020 Secretary of State John R. Ashcroft State Capitol Room 208 Jefferson City, MO 65101 www.sos.mo.gov John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State Cover image: A sunrise appears on the horizon over the Missouri River in Jefferson City. Photo courtesy of Tyler Beck Photography www.tylerbeck.photography The Missouri Roster 2019–2020 A directory of state, district, county and federal officials John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State Office of the Secretary of State State of Missouri Jefferson City 65101 STATE CAPITOL John R. Ashcroft ROOM 208 SECRETARY OF STATE (573) 751-2379 Dear Fellow Missourians, As your secretary of state, it is my honor to provide this year’s Mis- souri Roster as a way for you to access Missouri’s elected officials at the county, state and federal levels. This publication provides contact information for officials through- out the state and includes information about personnel within exec- utive branch departments, the General Assembly and the judiciary. Additionally, you will find the most recent municipal classifications and results of the 2018 general election. The strength of our great state depends on open communication and honest, civil debate; we have been given an incredible oppor- tunity to model this for the next generation. I encourage you to par- ticipate in your government, contact your elected representatives and make your voice heard. Sincerely, John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State www.sos.mo.gov The content of the Missouri Roster is public information, and may be used accordingly; however, the arrangement, graphics and maps are copyrighted material. -

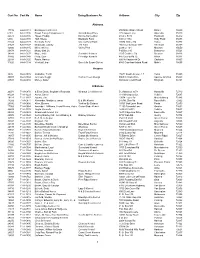

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

ESTIMATING the ECONOMIC BENEFITS of Levant Integration

ESTIMATING THE ECONOMIC BENEFITS of Levant Integration Daniel Egel Andrew Parasiliti Charles P. Ries Dori Walker C O R P O R A T I O N Acknowledgments We thank the New Levant Initiative for its support of this project; Keith Crane, Justin Lee, and Howard Shatz for their excellent feedback on earlier versions of this report and on the online calculator; Brian Phillips for his assistance in painstak- ingly reviewing the calculator; and Arwen Bicknell for her editing of this report. Andrew Parasiliti was director of the RAND Center for Global Risk and Security when he coauthored this study. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. is a registered trademark. For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2375. -

Introduction

Introduction The original intent of this study was to revisit the question of how developing and emerging-market economies should best integrate into global financial markets by taking stock of the literature and these economies’ experience with international capital flows since the 1990s. One important question, of course, is, What are the lessons and implica- tions of the global financial crisis for capital account policies in developing and emerging-market economies? As the crisis unfolded and the Great Recession took hold, however, it became clear that the crisis was deeply affecting the process of financial globalization itself and that our original question therefore had to be framed not only from the perspective of developing and emerging- market economies but also by looking at the system as a whole. The globalization of financial markets during the past 20 years did not occur by design. Free trade in financial assets has not been directed or supported by the type of international rules and institutions that the World Trade Organization (WTO) provides for the liberalization of trade in goods.1 Developing and emerging-market economies integrated into global financial markets in part because they expected to receive some dividends in terms of growth, but perhaps more fundamentally because of a particular under- standing of how the world economy is ordered and how financial globalization is aligned with the direction of history. The fundamental principle supporting financial globalization is that econ- 1. There are some exceptions, such as the prerequisite of capital mobility for EU membership and the fact that certain types of capital—such as foreign direct investment in services—are regulated under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). -

Run Date: 08/30/21 12Th District Court Page

RUN DATE: 09/27/21 12TH DISTRICT COURT PAGE: 1 312 S. JACKSON STREET JACKSON MI 49201 OUTSTANDING WARRANTS DATE STATUS -WRNT WARRANT DT NAME CUR CHARGE C/M/F DOB 5/15/2018 ABBAS MIAN/ZAHEE OVER CMV V C 1/01/1961 9/03/2021 ABBEY STEVEN/JOH TEL/HARASS M 7/09/1990 9/11/2020 ABBOTT JESSICA/MA CS USE NAR M 3/03/1983 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DIST. PEAC M 11/04/1998 12/04/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA HOME INV 2 F 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DRUG PARAP M 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA TRESPASSIN M 11/04/1998 10/20/2017 ABERNATHY DAMIAN/DEN CITYDOMEST M 1/23/1990 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT SPD 1-5 OV C 8/23/1993 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT IMPR PLATE M 8/23/1993 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 8/04/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI OPERATING M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI REGISTRATI C 9/06/1968 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA DRUGPARAPH M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA USE MARIJ M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OWPD M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA IMPR PLATE M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SEAT BELT C 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON -

One Size Fits Some : a Reassessment of EMU's Core–Periphery Framework

One Size Fits Some: A Reassessment of EMU’s Core–periphery Framework jei Journal of Economic Integration jei Vol.31 No.2, June 2016, 377~413 http://dx.doi.org/10.11130/jei.2016.31.2.377 One Size Fits Some : A Reassessment of EMU’s Core–periphery Framework Marcus Wortmann Georg-August-University Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany Markus Stahl Georg-August-University Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany Abstract This study provides a new multivariate assessment of core–periphery structures within the European Union. By applying different cluster algorithms to the broad set of Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure indicators, we detect a relatively stability-oriented and homogeneous group of European Union core countries that would be suitable for having a common currency. Unlike previous results, our analysis shows that countries such as the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Sweden would also fit well within such a hypothetical euro area. However, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain plus Cyprus and Croatia on the southern periphery, as well as most of the countries of the eastern enlargement are found to form very distinct clusters in terms of competitiveness, indebtedness, and economic performance. Our findings thus reveal that a single monetary policy can be appropriate only for some countries, even when measured using the official Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure scoreboard specifically designed to monitor the smooth functioning of the Economic and Monetary Union. * Corresponding Author: Marcus Wortmann; Georg-August-University Göttingen, Platz der Göttinger Sieben 3, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; Tel: +49 (0) 551 39 7355, Fax: +49 (0) 551 39 7093, E-mail: [email protected] goettingen.de.