Reminiscences of Farming Life in the 1920S (Newsletters 2 and 3) G.E.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GGAT 113 Mills and Water Power in Glamorgan and Gwent

GGAT 113: Mills and Water Power in Glamorgan and Gwent April 2012 A report for Cadw by Rachel Bowden BA (Hons) and GGAT report no. 2012/029 Richard Roberts BA (Hons) Project no. GGAT 113 The Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust Ltd Heathfield House Heathfield Swansea SA1 6EL GGAT 113 Mills and Water Power in Glamorgan and Gwent CONTENTS ..............................................................................................Page Number SUMMARY...................................................................................................................3 1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................4 2. PREVIOUS SCOPING..............................................................................................8 3. METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................11 4. SOURCES CONSULTED.......................................................................................15 5. RESULTS ................................................................................................................16 Revised Desktop Appraisal......................................................................................16 Stage 1 Assessment..................................................................................................16 Stage 2 Assessment..................................................................................................25 6. SITE VISITS............................................................................................................31 -

Vale of Glamorgan Council Buildings at Risk Survey 2011

Vale of Glamorgan Council Buildings at Risk Survey 2011 2006 – 2011 Change Analysis Sample Comparison Analysis - Summary 1 Sample Definitions Survey Status/Cycle Community Grade Use Group Detailed Use Cond Occ Own Risk Score/Assessment CEF Score Range S 1 2006 Full Survey * * * * * * * * - * 0 to 100 S 2 CURRENT * * * * * * * * - * 0 to 100 Average Scores Risk Assessment - Broad Average Scores No. in Sample % in Sample Difference S1 to S2 Condition Occupancy Risk Cat CEF S1 S2 S1 S2 No. % Sample 1 (S1) 3.305 2.789 4.914 83.292 At Risk 78 71 10.67 9.62 -7 -1.05 Sample 2 (S2) 3.348 2.817 4.978 84.719 Vulnerable 134 117 18.33 15.85 -17 -2.48 Difference S1 to S2 0.043 0.027 0.065 1.426 Not at Risk 519 550 71.00 74.53 31 3.53 % Difference S1 to S2 1.31 0.976 1.31 1.712 General Assessment The average condition of buildings in SAMPLE 2 is BETTER than that of buildings in SAMPLE 1 The average occupancy level of SAMPLE 2 is HIGHER than that of buildings in SAMPLE 1 The average risk score of buildings in SAMPLE 2 is HIGHER (less risk) than that of buildings in SAMPLE 1 The average CEF score of buildings in SAMPLE 2 is HIGHER than that of buildings in SAMPLE 1 CEF Assessment (Broad Defect Type Grouping) CEF Assessment (Rate of Change Grouping) % in Sample Difference S1 to S2 % in Sample Difference S1 to S2 S1 S2 % S1 S2 % No significant work required 38.44 41.06 2.62 No significant decay 38.44 41.06 2.62 Reduced maintenance levels 16.01 15.04 -0.96 Very slow rate of decline 16.01 15.04 -0.96 Maintenance backlog building up 15.18 16.12 0.94 Slow rate -

Project Newsletter Constitute Volume 1

EDITORIAL In this issue, as well as continuing with the 'A to Z' of place-names (we have reached letter 'C'), we are re-printing by kind permission of Mr J.M.Cleary of Acton, Wrexham, an excellent short article which he wrote for 'The Illtydian'(XXII.3.1950), the magazine of St Illtyd’s School, which was of course in Splott before it was moved to its present location in Llanrumney. It is fascinating to learn that Mr Cleary was born in what is now The Great Eastern Hotel in Metal Street, the former 16th century house of Thomas Bawdripp which became the homestead of the Upper Splott Farm. The name Bawdripp constantly crops up in our Roath records. We hold copies of the P.C.C. will of 1628 of William and the Llandaff diocesan will of Catherine (29.8.1662) and these will no doubt be referred to in later issues. Another forthcoming attraction is a second article by Mr J.M.Cleary, originally published in 'The Illtydian’ Summer 1964 entitled ‘Forty Years in Splott’. We also intend to publish the Surveys of the Manor of Roath Keynsham for 1650 and 1702. The first 10 numbers of the Project Newsletter constitute Volume 1. The burden of producing issues at monthly intervals is proving rather too heavy and thought will have to be given at the forthcoming A.G.M. to changing to a quarterly issue without reducing the quality or quantity of the annual output of material. FIELD VISITS The numbers attending some of our recent meetings have been disappointingly low, due no doubt to the holiday season being with us. -

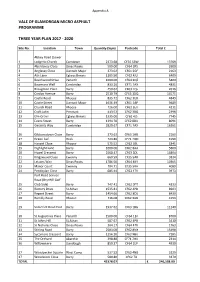

Amended Highway Resurfacing Appendix A

Appendix A VALE OF GLAMORGAN MICRO ASPHALT PROGRAMME THREE YEAR PLAN 2017 - 2020 Site No. Location Town Quantity (Sqm) Postcode Total £ Abbey Road (Lower 1 Lodge to Church Corntown 2373.68 CF35 5BW 13769 2 Aberdovey Close Dinas Powis 500.00 CF64 3PS 2900 3 Anglesey Close Llantwit Major 373.02 CF61 2GF 2163 4 Ash Lane Eglwys Brewis 1105.50 CF62 4JU 6409 5 Beechwood Drive Penarth 1000.00 CF64 3QZ 5800 6 Bowmans Well Cowbridge 833.26 CF71 7AX 4831 7 Broughton Place Barry 450.64 CF63 1QL 2616 8 Cardoc Avenue Barry 2510.79 CF63 1DQ 14575 9 Castle Road Rhoose 835.72 CF62 3EU 4849 10 Castle Street Llantwit Major 1636.49 CF61 1AP 9489 11 Church Road Rhoose 726.00 CF62 3EX 4211 12 Croft John Penmark 413.53 CF62 3BQ 2398 13 Elm Grove Eglwys Brewis 1335.00 CF62 4JS 7745 14 Evans Street Barry 1394.78 CF62 8DU 8091 15 Geraints Way Cowbridge 2820.67 CF71 7AX 16361 16 Gibbonsdown Close Barry 373.63 CF63 1AU 2169 17 Green Isaf Wick 723.86 CF71 7QD 4199 18 Havant Close Rhoose 575.52 CF62 3EL 3341 19 Highlight Lane Barry 1000.00 CF62 8AA 5800 20 Hywel Crescent Barry 2568.47 CF63 1DL 14894 21 Kingswood Close Ewenny 660.59 CF35 5AR 3834 22 Lettons Way Dinas Powis 1786.50 CF64 4BY 10365 23 Manor Court Ewenny 704.71 CF35 5RH 4089 24 Pendoylan Close Barry 685.44 CF63 1TX 3973 Port Road Service Road (Brynhill Golf 25 Club Side) Barry 747.41 CF62 9PT 4333 26 Rectory Drive St Athan 1535.81 CF62 4PD 8903 27 Regent Street Barry 1454.66 CF62 8DS 8439 28 Romilly Road Rhoose 716.08 CF62 3AU 4153 29 Somerset Road East Barry 1937.62 CF63 1BG 11240 30 St Augustines Place -

South Vale District Association – 15 Clubs Register of Affiliated Clubs 2018

SOUTH VALE DISTRICT ASSOCIATION – 15 CLUBS REGISTER OF AFFILIATED CLUBS 2018. 1. The date of the formation of the club is shown after name in brackets. 2. Telephone numbers are listed in these categories. (a) Club premises. (b) Hon. Secretary. (c) Mobile number. (d) Fixture secretary. (e) Fixture secretary’s mobile. Barry Athletic B.C. (1911) Membership 62 Postcode: CF62 5TQ Secretary: Tim Morgan (a) ‘Avoncroft’ Romilly Park Road, Barry, CF62 6RN (b) 01446 735838 email: [email protected] (c) 07513 473134 Fixture Sec: John Cauldwell (d) 01446 737551 10 St. Barucs Court, Plymouth Rd. Barry CF62 5UJ (e) 07581 037842 email: [email protected] Barry Central B.C. (1909) Membership 24 Postcode: CF62 8NA Secretary: Tom Kaged, 14 Aneurin Road, Barry, CF63 4PP (a) 01446 740104 email: [email protected] (b) 01446 406415 Fixture Sec: Tom Kaged (c) 07493 802708 Barry Romilly B.C. (1908) Membership 43 Postcode: CF62 6RN Secretary: Paul James (b) 01446 645687 21 A, Lakeside, Barry, CF62 6ST (c) 07773 293366 email: [email protected] (d) 01446 730360 Fixture Sec: Paul Clarke (e) 07926 584629 51 Bron Awelon, Barry CF62 6PS Email: [email protected] Belle Vue B.C. (1914) Membership 24 Postcode: CF64 1DA Secretary: Colin Scammell (a) 02920 709042 20 Beaufort Way, Rhoose, CF62 3BU (b) email: [email protected] (c) 07939 440272 Fixture Sec: Colin Scammell Cadoxton B.C. (1908) Membership 28 Postcode: CF63 2JS Secretary: Kelvin Chedgzoy (a) 01446 721705 6 Lidmore Road, Barry, CF62 7NF (b) 01446 742497 email: [email protected] (c) 07934 406485 Fixture Sec: Mike Curtis (d) 01446 743784 19 Coed-y-Capel, Barry CF62 8AF Cowbridge B.C. -

WRRC OS Map Collection

Welsh Railway Research Circle OS Map Collection – Scale 25 inch to mile GLAMORGANSHIRE II 12 Penller Fedwen, Bryn Melyn Quarry tramway 1918 16 Llangiwg, Betting Colliery, old tramway 1918 IV 13 Banwen, Maes y Marchog Colliery 1919 VI 10 Merthyr Common, Garth, Pant 1919 11 Llechryd, Rhymney Bridge Junction, LNWR, RR 1919 14 Dowlais, Pantyygallog, Ivor Works, LNWR, B&M, 1920 RR 15 Gelligaer, Rhymney, B&M, LNWR, RR 1919 16 Rhymney, Twyn Carno, LNWR, RR 1920 VII 4 Tyle Coch, Mynydd Mawr (no railway) 1916 8 Cwm Dulais, Birch Rock Colliery 1918 11 Craig Fawr, Craig Merthyr and Cefn Drum Colliery, 1918 Dulais Valley 12 Blaen Nant Ddu Reservoir, tramways, Dulais Valley 1916 15 Taylbont, Craig Merthyr Railway 1916 16 Felindre, Brynau Ddu Reservoir (no railway) 1916 VIII 1 Mynydd y Gwair (no railway) 1917 2 Mynydd Carn Llechart (no railway) 1918 3 Mynydd y Garth (no railway) 1918 4 Cwm Du, tramway 1918 5 Upper Lliw Reservoir, tramway 1917 6 Cwm Clydach, factory (no railway) 1917 7 Rhyd y Fro (no railway) 1918 8 Ynys Meudwy, Cilymaengwyn, canal, MR 1918 9 Felindre and Daren Colliery, tramways 1917 10 Rhyd y Gwin, Craig Cwm Colliery, tramway 1918 11 Pontardawe, MR, GWR earthworks only 1941 12 Pontardawe, Glanrhyd Tinplate, MR 1942 13 Lower Lliw Reservoir, tramway 1918 14 Cwm Clydach, Graigola Colliery and railway 1917 15 Pontardawe, Trebanos, Daren Colliery, canal, GWR, 1941 MR 16 Pontardawe, Alltwen, LMS 1942 IX 1 Ystalyfera, Ynys y Geinon Junction, LMS 1918 2 Rhos Common, N&B 1918 3 Dillwyn and Brynteg Collieries, N&B 1919 4 Dylas Higher, old tramway -

MGI Printing

LLANCARFAN SOCIETY Newsletter 42 November 1991 A PRESIDENT FOR THE SOCIETY Sir Keith Thomas, of the University of Oxford, has expressed his willingness to become the first President of our Society. We announce this with great pleasure as Sir Keith was not only brought-up in Llancarfan, son of Mr & Mrs Vivian Thomas, Pancross Farm, but also has acquired a world-wide reputation as a historian, with particular emphasis on affairs of the countryside. Amongst his books are Man and the Natural World and Religion and the Decline of Magic. The last named won a Wolfson Literary Award for History. He was educated at Llancarfan Primary School, Barry County Grammar School and Balliol College, Oxford, before commencing his academic career. Sir Keith was awarded his knighthood in 1988 for services to the study of history. FUTURE EVENTS The ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING will be held in the Llancarfan Community Hall at 7.30 p.m. on January 24th 1992. Nominations for the officers of the Society should be sent to the Hon. Secretary, Barbara Milhuisen (address below), or a Committee member. Nominees must have expressed willingness to stand and a seconder is needed. Our Chairman, Derek Higgs wishes to retire and so we shall definitely need a nomination for a new Chairman. All other officers have expressed willingness to serve during 1992. Following the formal A.G.M., there will be a CHEESE AND WINE PARTY AND A SLIDE- SHOW as last year. WHIST DRIVE: We may just be in time to remind you of the whist drive to be held on November 22nd at 7.30 p.m. -

MGI Printing

LLANCARFAN SOCIETY Website: www.llancarfansociety.org.uk NEWSLETTER 137 President: Phil Watts Chairman: Mike Crosta DECEMBER 2008 Secretary: Gwyneth Plows 3 Showle Acre, Rhoose, CF62 3HZ, Tel. 01446 713533 Contributions to the Newsletter to: Ann Ferris, Fordings, Llancarfan CF62 3AD., or to Alan Taylor by email to [email protected] Subscriptions/Membership Secretary Audrey Porter, Millrace Cottage, Llancarfan CF62 3AD. Mailing Enquiries: John Gardner, The Willows, Fonmon, CF62 5BJ Tel. 01446 710054. Local Church Christmas Services Thursday, 18th December 7.00pm Llantrithyd Carol Service LEGEND HAS IT THAT Sunday, 21st December ST CADOC WAS AIDED BY A DEER WHEN HE BUlLT 6.00pm Carol Service in Penmark HIS MONASTERY IN LLANCARFAN 7.30pm Carol Service in Llancarfan Christmas Eve 11.30pm Penmark Local Births, Funerals, Marriages etc. 11.30pm Llancarfan Baptisms Christmas Day Lara Grace Clarke 30th March 9.00am Penmark Isabelle Elizabeth Spencer 13th April 9.15am Llantrithyd Manon Rose Evans 31st August 11.00am Llancarfan Marriages TUESDAY CLUB PROGRAMME 2nd July Kevin Joseph Conneely to Rebecca Jane DEC 16th Party 7.30pm Games and Nibbles Teesdale Please bring a "lucky dip" gift value about £1 and a plate of nibbles, non members welcome , do join us 13th Sept for some fun. Edward Thomas Davies to Jamie Louise Powell JAN 20 LUNCHING OUT FEB 17 Speaker to be arranged Funerals MAR 17 AGM (then some games and refreshment) Lynnus Ivor Price 15th March APR ? JUMBLE SALE Date to be arranged Chair: Audrey Porter 781328 Sec: Audrey William Rowland Whitworth 4th Sept Baldwin 781416 Treasurer: Ann Ferris 781350 Douglas Henry Chugg 3rd Oct. -

Planning Committe Agenda 8 September

Agenda Item No. THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE : 8 SEPTEMBER, 2016 REPORT OF THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING 1. BUILDING REGULATION APPLICATIONS AND OTHER BUILDING CONTROL MATTERS DETERMINED BY THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING UNDER DELEGATED POWERS (a) Building Regulation Applications - Pass For the information of Members, the following applications have been determined: 2016/0009/PV AC 1,Lidmore Road, Barry Two storey extension 2016/0588/BR AC 3, Meadow Lane, Penarth To extend the habitable roof space by building a Dutch gable above the existing garage, to extend the existing garage, and convert the garage to residential use, and other internal alterations 2016/0614/BR AC 10, Westgate, Cowbridge Single storey extension to rear and annexe for office and additional bedroom and garage 2016/0641/BR AC 22, Church Hill Close, Alterations to roof / and Llanblethian first floor 2016/0642/BR AC 30, Millfield Drive, 2 storey extension. Cowbridge 2016/0647/BN A 123, Court Road, Barry Fire door and frame to kitchen (FD30) 2016/0649/BN A 14, Longmeadow Drive, Single storey kitchen and Dinas Powys utility room extension 2016/0650/BR AC 21, Britten Road, Penarth. Erection of single storey CF64 3QJ garden room to rear of dwelling. P.1 2016/0651/BN A Primrose Cottage, 54, 1) Removal of poly- Hillside Drive, Cowbridge, carbonate roof on existing Vale of Glamorgan CF71 conservatory & replace 7EA with thermally efficient flat warm roof with roof lantern. 2) Replace old, ill fitting French doors with modern thermally efficient French doors. 3) Create new opening in kitchen & fit new external door. -

Planning Committee 14 01 2016 Reports

Agenda Item No. THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE : 14 JANUARY 2016 REPORT OF THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING 1. BUILDING REGULATION APPLICATIONS AND OTHER BUILDING CONTROL MATTERS DETERMINED BY THE DIRECTOR UNDER DELEGATED POWERS (a) Building Regulation Applications - Pass For the information of Members, the following applications have been determined: 2015/1389/BN A 3, Darren Close, Front extensions and Cowbridge refurbishment 2015/1626/BN A 23, Cardiff Road, Dinas Removal of chimney & Powys install steels. 2015/1627/BN A 11. Downfield Close, Open up doorway between Llandough kitchen & dining room. 2015/1630/BR AC 112, South Road, Sully Remove existing roof to building and replace roof with new including three bedrooms and two bathrooms, in dormer extension. 2015/1631/BN A 7, Nant Talwwg way, Barry Single storey extension and garage. 2015/1632/BN A 11. Glyn y Gog, Rhoose Single storey conservatory extension to include knockthrough into house. 2015/1634/BN A 5, Warwick Way, Barry New slate roof up & over 2015/1637/BN A 171, Court Road, Barry installation of steel beams and re-build of masonry above 2015/1648/BR AC Unit A, (Cafe), The Pump Fit Out House, Hood Road, Barry 2015/1649/BR AC Unit B (Restaurant), The Fit out for new restaurant Pump House, Hood Road, within existing unsed Barry commercial unit P.1 2015/1650/BR AC Unit C & D (Gym), The Fit out works to build new Pump House, Hood Road, gym within existing Barry commercial unit 2015/1653/BN A Great Frampton Farm, Conversion of derelict farm Llantwit Major CF61