Nuno Severiano Teixeira Daniel Marcos a Historical Perspective Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public and Private Institutions in Contracting Parties (.Pdf)

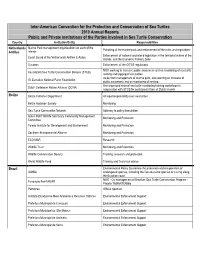

Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles 2010 Annual Reports Public and Private Institutions of the Parties Involved in Sea Turtle Conservation Country Institution/Entity Responsabilities Marine Park management organizations on each of the Netherlands Patrolling of the marine park and enforcement of the rules and regulations Antilles islands Enforcement of national and island legislation in the territorial waters of the Coast Guard of the Netherlands Antilles & Aruba islands, and the Economic Fishery Zone Customs Enforcement of the CITES regulations NGO working to increase public awareness and on monitoring of sea turtle Foundation Sea Turtle Conservation Bonaire (STCB) nesting and tagging of sea turtles. Aside from management of marine park, also working on increase of St. Eustatius National Parks Foundation public awareness and on monitoring of nesting. Has organized several sea turtle monitoring training workshops in Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance (DCNA) cooperation with STCB for participants from all Dutch islands Belize Belize Fisheries Department All legal responsibility over sea turtles Belize Audubon Society Monitoring Sea Turtle Consrvation Network Advisory to policy formulation Gales Point Wildlife Sanctuary Community Management Monitoring and Protection Committee Toledo Institute for Development and Environment Monitoring and Protection Southern Environmental Alliance Monitoring and Protection ECO MAR Research Wildlife Trust Monitoring and Protection Wildlife Conservation Society Training, -

Copa Petrobrás De Tênis Em Aracaju

ARTIGO 4 COPA PETROBRAS DE TÊNIS EM ARACAJU: OUT!1 André Marsiglia Quaranta Sérgio Dorenski D. Ribeiro 1 Este estudo é fruto das primeiras pesquisas realizas na Orla de Atalaia pelo LaboMídia/UFS e que fora publicado no Livro Educação Física e Sociedade: Temas Emergentes vol. 3, com o título: PROJETO ORLA E O DESTAQUE DAS COMPETIÇÕES ESPORTIVAS: O Caso da Copa Petrobras de Tênis. Este novo título representa uma alusão à saída da etapa em Aracaju e ao término do torneio. pprojetorojeto oorlarla - mmioloiolo 9595 330/05/120/05/12 115:085:08 pprojetorojeto oorlarla - mmioloiolo 9696 330/05/120/05/12 115:085:08 Página | 97 INTRODUÇÃO Hoje, a orla da praia de Atalaia em Aracaju/SE se confi gura - em sua ar- quitetura e disponibilização do espaço físico, envolvendo a beleza natural e as áreas construídas - numa das belas estruturas turísticas do Brasil. Reformula- da para diversas práticas esportivas, de lazer e outros entretenimentos (pista de kart, aeromodelismo, pistas de skate e patins, oceanário, entre outros), a orla deslumbra-se em um lugar “ideal” no tocante as opções de lazer para os Aracajuanos e demais visitantes. Diante deste local estão situados os melhores hotéis do Estado, o que viabiliza o fl uxo de turistas. Este é um aspecto que nos chama atenção, pois algumas competições – de caráter nacional e internacional – como foi o caso da Copa Petrobras de Tênis (CPT)2, são realizadas ali. Neste estudo, verifi camos que alguns espaços - dentro da esfera pública – caracterizam-se com a marca da privatização, a exemplo das quadras de tênis, o kartódromo, o oceanário, etc. -

ATP Challenger Tour by the Numbers

ATP MEDIA INFORMATION Updated: 20 September 2021 2021 ATP CHALLENGER BY THE NUMBERS Match Wins Leaders W-L Titles 1) Benjamin Bonzi FRA 49-11 6 2) Tomas Martin Etcheverry ARG 38-13 2 3) Zdenek Kolar CZE 29-18 3 4) Holger Rune DEN 28-7 3 5) Kacper Zuk POL 26-11 1 Nicolas Jarry CHI 26-12 1 7) Sebastian Baez ARG 25-5 3 Altug Celikbilek TUR 25-10 2 Juan Manuel Cerundolo ARG 25-10 3 Tomas Barrios Vera CHI 25-11 1 11) Jenson Brooksby USA 23-3 3 Gastao Elias POR 23-12 1 Win Percentage Leaders W-L Pct. Titles 1) Jenson Brooksby USA 23-3 88.5 3 2) Sebastian Baez ARG 25-5 83.3 3 3) Benjamin Bonzi FRA 49-11 81.7 6 4) Holger Rune DEN 28-7 80.0 3 5) Zizou Bergs BEL 19-6 76.0 3 6) Federico Coria ARG 18-6 75.0 1 7) Tomas Martin Etcheverry ARG 38-13 74.5 2 8) Arthur Rinderknech FRA 18-7 72.0 1 Botic van de Zandschulp NED 18-7 72.0 0 *Minimum 20 matches played* Singles Title Leaders ----- By Surface ----- Player Total Clay Grass Hard Carpet Benjamin Bonzi FRA 6 1 5 Sebastian Baez ARG 3 3 Zizou Bergs BEL 3 1 2 Jenson Brooksby USA 3 1 2 Juan Manuel Cerundolo ARG 3 3 Tallon Griekspoor NED 3 3 Zdenek Kolar CZE 3 3 Holger Rune DEN 3 3 Franco Agamenone ITA 2 2 Daniel Altmaier GER 2 2 Altug Celikbilek TUR 2 2 Mitchell Krueger USA 2 2 Tomas Martin Etcheverry ARG 2 2 Mats Moraing GER 2 2 Carlos Taberner ESP 2 2 Bernabe Zapata Miralles ESP 2 2 53 tied with 1 title each Winners by Age: 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 0 0 6 7 8 4 7 10 13 13 4 3 7 5 3 1 0 3 0 1 0 1 0 0 Youngest Final: Juan Manuel Cerundolo (19) d. -

And Type in Recipient's Full Name

ATP MEDIA INFORMATION ATP CHALLENGER TOUR BY THE NUMBERS FINAL 2019 VERSION 2019 Win-Loss Pct. Leaders W-L Pct. Titles 1) Ricardas Berankis LTU 24-3 .889 4 2) Tommy Paul USA 30-5 .857 3 3) Ugo Humbert FRA 21-5 .808 3 4) Jannik Sinner ITA 28-7 .800 3 5) Mikael Ymer SWE 39-10 .796 4 6) Alejandro Davidovich ESP 34-11 .756 1 7) Emil Ruusuvuori FIN 36-12 .750 4 8) Jozef Kovalik SVK 28-10 .737 2 9) James Duckworth AUS 49-18 .731 4 10) Gregoire Barrere FRA 26-10 .722 2 11) Soon-woo Kwon KOR 35-14 .714 2 Hugo Dellien BOL 25-10 .714 2 Alexander Bublik KAZ 20-8 .714 3 14) Andrej Martin SVK 47-19 .712 3 15) Chris O’Connell AUS 32-13 .711 2 *Minimum 25 matches played* Match Wins Leader: James Duckworth AUS – 49 wins 2019 Singles Title Leaders: ----- By Surface ----- Player Total Clay Grass Hard Carpet Ricardas Berankis LTU 4 4 James Duckworth AUS 4 1 3 Emil Ruusuvuori FIN 4 4 Mikael Ymer SWE 4 1 3 Pablo Andujar ESP 3 3 Alexander Bublik KAZ 3 3 Ugo Humbert FRA 3 3 Gianluca Mager ITA 3 2 1 Andrej Martin SVK 3 3 Thiago Monteiro BRA 3 3 Tommy Paul USA 3 1 2 Jannik Sinner ITA 3 3 Biggest Movers To Top 100 Ranking Jump Year-End 2018 – 2019 ’19 Titles 1) Jannik Sinner ITA +685 763 – 78 3 2) Jo-Wilfried Tsonga FRA +230 259 – 29 1 3) Mikael Ymer SWE +207 281 – 74 4 4) Soonwoo Kwon KOR +165 253 – 88 2 5) Daniel Evans GBR +157 199 – 42 2 6) James Duckworth AUS +145 245 – 100 4 7) Alejandro Davidovich Fokina ESP +144 231 – 87 2 Youngest Finals: Nicola Kuhn (19) d. -

Commencement Flyer

FPO UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI COMMENCEMENT2020 SPRING AND SUMMER UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI COMMENCEMENT2020 SPRING AND SUMMER Graduate School School of Architecture College of Arts and Sciences Patti and Allan Herbert Business School School of Communication School of Education and Human Development College of Engineering Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine Phillip and Patricia Frost School of Music School of Nursing and Health Studies Message from the President JULIO FRENK To the Class of 2020, Congratulations! You are now prepared to undertake the next stage of your personal and professional development. Your education has equipped you with a unique skill set enriched by the experiences you have gained here at the University of Miami. The relationships you have forged with faculty, advisers, and fellow students have not only strengthened our community, but will undoubtedly be a source of community and strength throughout your career. I have always had an unwavering belief in your ability to persevere, but you have truly exhibited in an outstanding way the characteristics of caring and resilient ’Canes in the face of challenges such as hurricanes and now, the COVID-19 pandemic. This unprecedented emergency, which for the time being has transformed learning and upended life as we know it, forced the postponement of our spring commencement ceremonies until December. But that in no way affects your degree status, nor our immense pride in your accomplishments. I know you must feel frustration and disappointment at not being able to celebrate together at this time. If you choose to return in December, we will celebrate then. -

Men's Tennis Activity Career WOLMARANS, Fritz

Men's Tennis Activity Career WOLMARANS, Fritz (RSA) Date of Birth: 7 Mar 1986 International Junior Tournament of Tunisia (African Warm-up) (TUN) G3 26 Mar 2002 - 30 Mar 2002 R64 W Liberty NZULA (ZIM) 6-2 6-1 R32 W Jose NENGANGA (ANG) 6-7(6) 6-2 6-3 R16 W Kamil FILALI (MAR) 6-4 2-6 6-1 QF L Hicham BALBAA (EGY) 3-6 4-6 Career W/L: 3 - 1 Entry: Q Seed: Ranking Points: 20 International Junior Tournament of Tunisia (African Warm-up) (TUN) G3 26 Mar 2002 - 30 Mar 2002 Partner: Christopher WESTERHOF (RSA) R16 W Eric HAGENIMANA (RWA) / Jose NENGANGA (ANG) 6-4 6-2 QF W Hicham BALBAA (EGY) / Mohammed FAWZY (EGY) 6-3 6-4 SF W Haithem ABID (TUN) / Malek JAZIRI (TUN) 6-4 4-6 7-6(4) FR W Christian BLOCKER (GER) / Tiago GODINHO (POR) 6-3 6-7(1) 6-1 Career W/L: 7 - 1 Entry: Seed: Ranking Points: 50 International Junior Tournament of Tunisia (African Warm-up) (TUN) G3 26 Mar 2002 - 26 Mar 2002 R32 W Sabri FALLAHI (TUN) 6-1 6-1 R16 W Karim BELHADJ (GBR) 6-1 6-1 Career W/L: 7 - 1 Entry: Seed: Ranking Points: 0 French Riviera International Junior Open (FRA) G3 08 Apr 2002 - 14 Apr 2002 Partner: Luques MAASDORP (RSA) Clay(O) R16 L Mathieu BLANC (FRA) / Sebastian LOUIS (FRA) 3-6 4-6 Career W/L: 7 - 2 Entry: Seed: Ranking Points: 0 Istres International Junior Tournament (FRA) G2 15 Apr 2002 - 21 Apr 2002 Partner: Luques MAASDORP (RSA) Clay(O) R16 W Paterne MAMATA (FRA) / Gael MONFILS (FRA) 6-2 6-1 QF L Steve DARCIS (BEL) / Andis JUSKA (LAT) 4-6 2-6 Career W/L: 8 - 3 Entry: Seed: Ranking Points: 20 Tournoi International Junior de Beaulieu Sur Mer Qualifying -

Classificação Geral Masculino

CLASSIFICAÇÃO GERAL MASCULINO GRANDE VITÓRIA > ARACRUZ; CARIACICA; GUARAPARI; SERRA; VIANA; VILA VELHA. INSPETOR PENITENCIÁRIO - DT C. C. Total de Pontos por Pontos Por Sexo Posição Geral Nome Inscrição Dt de Nasc. Negros Indígenas Pontos Título Exper. 1 Ricardo Rais Rodrigues 1706726 1 55 20 35 21/02/1978 M 2 Patrik Gonçalves Dos Santos 1705796 55 20 35 07/06/1978 M 3 André Leite Linhares 1698384 55 20 35 29/09/1981 M 4 Max Rogério De Araujo 1704295 2 55 20 35 12/03/1983 M 5 Alexsandro Rossi Rodrigues 1708681 55 20 35 24/06/1995 M 6 Felipe Oliveira Da Silva 1700110 55 20 35 28/05/1996 M 7 Dielson Café Santanna Filho 1712548 50 15 35 18/04/1966 M 8 Ides Claudio Torezani 1703184 50 15 35 27/07/1972 M 9 Adriano Gonçalves Firmino 1713291 50 15 35 03/01/1975 M 10 João Lucas De Lima Rodrigues 1707422 50 15 35 02/10/1992 M 11 Breno Mendes Orlando 1699684 3 50 20 30 16/12/1981 M 12 Amarildo Pereira Ignácio 1712816 45 10 35 16/06/1968 M 13 Eduardo Gonçalves Vieira 1700711 45 10 35 18/07/1976 M 14 Bruno Dos Reis Dias 1705979 45 10 35 29/06/1979 M 15 Fagner Da Silva Lovato 1704294 1 45 10 35 01/12/1981 M 16 Jean Lucas 1715042 4 45 10 35 07/06/1998 M 17 Edmilson Caetano Ferreira 1713242 45 15 30 01/05/1961 M 18 Carlos Magno Do Nascimento 1705026 45 15 30 04/09/1971 M 19 Sergio Luzia Cristo 1701646 5 45 20 25 08/05/1970 M 20 Vagner Aguiar Da Silva 1700374 45 20 25 26/10/1971 M 21 Agnaídio Paixão Dos Santos 1709875 45 20 25 06/08/1976 M 22 Gilmar Martins Da Costa 1701047 45 20 25 10/08/1977 M 23 Sidnei Lords Moreira 1703649 45 20 25 01/12/1977 M 24 -

Publication of the Cat News N° 69: 30 July 2009

TENNIS NEWS N° 67 / January – February 2009 N° 68 / March - April 2009 Inside this Issue 1. Inauguration of the Francophone Tennis Training Centre in Dakar. 2. 32nd African Junior Championships – Casablanca – Morocco April 2009. 3. The CAT Year 2008. 4. CAT Annual General Meeting Casablanca – Morocco, 16 & 17 April 2009. 5. African Zones Juniors Championships – January 2009. 6. African 14 & U Circuit – Legs of Algeria, Tunisia, Kenya & Tanzania 2009. 7. Challengers in Africa. 8. Coaches & Play and Stay Courses in Africa. 9. News from National Associations and Regions 10. Results of the African tournaments and Upcoming Events. 11. CAT Officiating 12. African Rankings Inauguration of the Francophone Tennis Training Centre in Dakar - ITF/CAT/FST 28 -29 January In his quality of President of the Confederation of African Tennis (CAT), Mr. Tarak Chérif made a work visit in Senegal from January 27th until the 29th, 2009 to preside the official ceremony of the inauguration of the new Francophone Tennis Training Centre based in the Senegalese capital and to work out a protocol of co-operation between the CAT and the CONFEJES (Conference of the Ministers for the Youth and the Sports of the States having the French in common). Mr. Chérif was accompanied by Mr. Dave Miley, Executive Director of Development at the International Tennis Federation. The President of the “Fédération Sénégalaise de Tennis” has also invited Mr Mohamed M’jid, President of the “Fédération Royale Marocaine de Tennis”. During his visit, Mr. Chérif was received by Mr. Sheik Aguibou Soumaré Prime Minister of Senegal, it had also discussions with Mr. -

Annual Report & Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31St July 2010

T6701-AELTC-G.Acc Cover 10 Yellow:T4624-AELTC-G.Acc Cover 17/11/10 11:13 Page 2 THEALLENGLANDLAWNTENNIS GROUNDPLC Annual Report & Financial Statements for the year ended 31st July 2010 T6701-AELTC-G.Acc 10 Yellow:T4624-AELTC-G.Acc 18/11/10 13:22 Page 1 The All England Lawn Tennis Ground plc and subsidiary undertakings Contents Officers and Professional Advisers Officers and Professional Advisers ................1 Directors .......................................................... Report of the Directors ...........................3 - 6 J A H Curry CBE FCA (Chairman) Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities ........6 P W Bretherton Independent Auditors’ Report ......................7 J S Dunningham OBE D P Howorth FCA Consolidated Profit and Loss Account ..........8 T D Phillips CBE Consolidated Balance Sheet .........................9 S G Smith OBE FRICS Company Balance Sheet.............................10 Secretary .......................................................... Consolidated Cash Flow Statement............11 R G Atkinson FCMA Notes to the Financial Statements.......12 - 20 Auditors ........................................................... Deloitte LLP Chartered Accountants Hill House 1 Little New Street London EC4A 3TR Solicitors .......................................................... CMS Cameron McKenna Mitre House 160 Aldersgate Street London EC1A 4DD Bankers ............................................................ HSBC Bank plc West End Corporate Banking Centre 70 Pall Mall London SW1Y 5EZ Registrars and Transfer -

Prize Money and Media Value in Tennis: Who Leads the Spectacle?

Prize Money and media value in tennis: who leads the spectacle? Pedro Garcia-del-Barrio ([email protected]) ESI-rg and Universtitat Iternacional de Catalunya Immaculada 22 08017 Barcelona. SPAIN Tf. +34 93 2541800 / Fax: +34 93 2541850 and Francesc Pujol ([email protected]) ESI-rg and Universidad de Navarra Edificio Bibliotecas (entr. Este) 31080 Pamplana. SPAIN Tf. +34 948 425625 / Fax: +34 948 425626 March 2011 Abstract Given the economic and commercial implications of sports, the media value of players is considered the main asset in the area of professional sports businesses. This paper aims to establish procedures to measure intangible assets within the tennis industry, an exciting market within the business of spectacle. In addition to evaluate the media value of tennis players, this study examines the extent to which policies on prize money could be more efficiently designed to account for the economic contribution of the different agents involved in the spectacle. In order to rank the media value of professional tennis players, we have followed the innovative ESI-rg methodology, whose basic guidelines develop upon the notion of media value by combining information on popularity and notoriety. The paper has been carried out using weekly data on notoriety and popularity for the main 1,400 professional tennis players (700 women competing on the WTA and another 700 men on the ATP). Key Words: Career opportunities. Evaluating intangible assets. Media value. Sports’ industry. Professional tennis. Discrimination. JEL-Code: J24, J33 y J71. 1. Motivation and main results of the paper This paper aims to assess the economic value of intangible assets within the tennis industry. -

Working Paper Nº 01/13

Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales Working Paper nº 01/13 Sport Talent, Media Value and Equal Prize Policies in Tennis Pedro Garcia-del-Barrio Universitat Internacional de Catalunya Francesc Pujol University of Navarra Sport Talent, Media Value and Equal Prize Policies in Tennis Pedro Garcia-del-Barrio, Francesc Pujol Working Paper No.01/13 February 2013 ABSTRACT Given the economic and commercial implications of sports, the media value of players and teams is considered a major asset in professional sports businesses. This paper aims to assess the economic value of intangible assets in the tennis industry. In order to rank the media value of professional tennis players (both men and women), we measure the intangible talent of players based on their exposure in the mass media. We use the ESI (Economics, Sports and Intangibles) methodology to examine some issues related to the competitive structure of tennis. Then, we explore whether policies regarding prize money could be more efficiently designed to account for the economic contribution of the players. The paper uses weekly data on the media presence and popularity of 1,400 professional tennis players (700 women and 700 men competing in 2007, respectively, in the WTA and ATP). Pedro Garcia-del-Barrio Economia i Organització d'Empresas Universitat Internacional de Catalunya [email protected] Francesc Pujol School of Economics and Business Administration University of Navarra [email protected] Sport Talent, Media Value and Equal Prize Policies in Tennis Pedro Garcia‐del‐Barrio Universtitat Internacional de Catalunya ([email protected]) Francesc Pujol Universidad de Navarra ([email protected]) Abstract Given the economic and commercial implications of sports, the media value of players and teams is considered a major asset in professional sports businesses. -

Media Guide 2012 Olympic Tennis Event

Adjust width of spine as necessary MEDIA GUIDE MEDIA 2012 Olympic Tennis Event Tennis 2012 Olympic International Tennis Federation Bank Lane, Roehampton www.itftennis.com London SW15 5XZ www.itftennis.com/olympics MEDIA GUIDE 2012 Olympic Tennis Event Olympic_covers_aw_160611.indd 1 16/06/2011 15:16 2012 olympic tennis event meDiA GUiDe THE GAMES OF THE XXX OLYMPIAD LONDON, GREAT BRITAIN International Tennis Federation Bank Lane, Roehampton London SW15 5XZ Telephone: +44 (0)20 8878 6464 www.itftennis.com/olympics | www.itftennis.com/olimpiadas Editor: Emily Bevan Design: Anthony Collins Creative Printing: Remous Photographs by © International Olympic Committee, Tommy Hindley, Paul Zimmer Reproduction of this work in whole or in part without the prior permission of The International Tennis Federation is prohibited Copyright © 2012 International Tennis Federation All Rights Reserved 2012 Olympic Media Guide 1 Elena Dementieva (RUS) 2 2012 Olympic Media Guide csontent 4 Message from the President 31 Historical Player Lists by Country 5 Tennis in the Olympics 32 Men 7 2012 Match Schedule 60 Women 8 2012 Event Information 9 2012 Administration 79 Results 80 Men’s Singles 11 General Information 90 Men’s Doubles 12 Host Nations 98 Women’s Singles 13 Medal Winners 104 Women’s Doubles 17 Nation Medal Table 108 Mixed Doubles 18 Entries and Nation Representation 19 Tripartite Commission Invitation places 111 Summary of Rules & Regulations 112 Rules and Regulations Summary 21 Statistics 22 Most Games in a Match 117 Olympic Abbreviations 22 Fewest Games in a Match 118 Country Codes 23 Most Games in a Set 23 Most Games in a Final 24 Unfinished Matches 25 Whitewash Matches 25 Players Winning both Singles and Doubles Events at the same Olympic Games 26 Leading Medal Winners 26 Players competing at 4 or more Olympics 26 Most Olympics Contested 26 Miscellaneous 28 Youngest and Oldest Champions 29 Youngest and Oldest Medallists 2012 Olympic Media Guide 3 mGessA e from the presiDent It gives me great pleasure to introduce the Media Guide for the 2012 Olympic Tennis Event.