The Next Generation LICENSED EVENTING OFFICIALS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia Eventing Rules 2018 Proposed Rules Changes: Draft

Zambia Eventing Rules 2018 Proposed Rules Changes: Draft Document CONTENTS Affiliated Eventing ZANEF Code of Conduct Membership and Horse Registration; Minimum Eligibility Requirements Event Officials; Zambia Eventing OFFICIALS Team Duties; Disciplinary Sanctions The Entries Process; Withdrawals and Refunds; Cancellation and Abandonment The Competition; General Guidance and Rules of Participation The Competition; The Individual Phases Competitors’ Dress and Saddlery Equipment Scoring, Objections, and Enquiries; Prizes; Points and Grading Medical, including Medical Cards; Falls and Medical Checks; Prohibited Substances; Medical Team and Equipment Veterinary, including Vaccinations and Passports; Equine Anti-doping and Controlled Medication; Veterinary Team and Equipment Organisation and Administration; Rights and Policies Entry Fees; Abandonment Premium; Start Fees (tbc) International (FEI) Competition Examples of Refusals, Run-Outs, and Circles CHAPTER 1 AFFILIATED EVENTING & ZAMBIA ZANEF EVENTING CODE OF CONDUCT AFFILIATED EVENTING 1.1 Zambia National Equestrian Federation (ZANEF) is the governing body for Affiliated Eventing in Zambia, ZANEF regulates and supervises all Events which are affiliated to it. 1.2 The ZANEF Eventing Rules, which form the framework for the conduct of National Events, are contained in this handbook document.Whenever amendments are necessary, notice will be given to members by all reasonable and appropriate means. 1.3 Zambia Eventing operates under The Zambia National Equestrian Federation (ZANEF) which is affiliated to the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI), the world governing body of equestrian sport. The FEI has made Rules for the conduct of all INTERNATIONAL EVENTS which are set out in full at www.fei.org 1.4 All Eventing competitions. National and International, consist of three separate phases; dressage, show jumping and cross country, which must be carried out by the same Horse and rider. -

All the Regulars & Find out What Many Different Maine & NH

The Horse's Maine & NH 153A Pickpocket Rd. Brentwood, NH 03833 & Maine and NH's Own Equestrian Newspaper April 2016 $2.00 Cyan Magenta Yellow Yellow Black 1 All the Regulars & Find Out What Many Different Maine & NH POSTAL CUSTOMER POSTAL Associations and Barns Have in ECRWSS April 2016 The Horse's MaineStore & NH for YOU in 2016Page 1 improved top line prebiotics + probiotics working together Nutri-Bloom Advantage® for increased fiber digestion formulated to help horses prone to colic 2 Cyan Magenta He’ll never know he’s aging. Research backed. Proven results. Yellow Yellow nutrenaworld.com/happybelly Black Senior Visit safechoicetrial.com for coupon NUTRENA® SAFECHOICE® IS AVAILABLE AT THE FOLLOWING LOCATIONS: MAINE Welch’s Hardware & Lumber Clark’s Grain Store Osborne’s Agway Ames Farm Center Lebanon, ME Ossipee, NH Belmont, NH North Yarmouth, ME 207-457-1106 603-539-4006 603-527-3769 www.clarksgrain.com 207-829-5417 Osborne’s Agway NEW HAMPSHIRE Concord, NH Andy’s Agway Achille Agway Hilltop Feeds Dayton, ME Peterborough, Milford Loudon, NH 603-228-8561 603-441-4483 207-282-2998 Keene and Walpole Osborne’s Agway Andysagway.com 603-784-5426 603-783-4114 Hooksett, NH www.hilltopfeeds.com 603-627-6855 Mac’s True Value Hardware Clark’s Grain Store Unity, ME Chichester, NH Newton Grain 207-948-3800 603-435-8388 & Feed Supply Inc. Newton, NH clarksgrain.com Maine Horse & Rider 603-382-8553 Tack and Farm Store 603-548-5118 Holden, ME 207-989-7005 Mainehorseandrider.com © 2016 Cargill, Inc. All Rights Reserved Nutrena_Safechoice_SR_Spring_Dealers.indd 1 3/9/16 10:03 AM Page 2 The Horse's Maine & NH April 2016 and its many stages in their own NHDEA Holds Annual horses and family pets. -

Braiding Manes and Tails: a Visual Guide to 30 Basic Braids (Storey, 2008)

THE DRESSAGE RIDER’S HOW-TO GUIDE Braids? Polo wraps? We’ve got you covered. BY SHARON BIGGS IMPECCABLE: Beautiful braids, correctly ftting tack and attire, and excellent grooming complement the bloom of health and present your horse to his best advantage. Stefen Peters presents Ravel at the 2012 Olympic Games veterinary inspection. JENNIFER BRYANT 30 October 2012 t USDF CONNECTION very equestrian sport has a particular way of turning out horse and rider for competition, and dressage is no diferent. To call yourself a true DQ (that’s “dressage queen” for the uninitiated), Eyou need to master the big three: braiding, tail prep, and polo-wrap application (the latter of which will also come in handy should your horse’s legs need to be bandaged). You also need to know how to select and adjust a saddle pad for a fattering look and maximum horse comfort. In this article, a grooming expert and a tack-shop owner HUNTER BRAIDS: ofer step-by-step instructions. Bonus: A dressage judge Can be tied so they lie fat against the neck or with little knobs at the top, as shown here and longtime competitor and horse owner shares her pet peeves and advice on show turnout. How to: Braid for Dressage First, the rules. Although the US Equestrian Federation Rule Book states that braiding the horse’s mane for dres- sage is optional, the unwritten rule is always to braid, except perhaps for unrecognized competitions (schooling shows). Most dressage riders consider braiding a traditional form of showing respect for the judge and the competition, as well as a way of enhancing the look of their horses’ necks. -

The Century Club News

A regularly issued letter Volunteer Editor: to and about the members of Carole Nuckton The Dressage Foundation’s (Bend, Oregon) Century Club. Team #52 THE NEWS CenturyISSUE 16Club / JANUARY 2012 “You are never too old to set another goal or to dream a new dream.” – C.S. LEWIS ISSUE 16 / JANUARY 2012 THE CENTURY CLUB NEWS published by THE DRESSAGE FOUNDATION 1314 ‘O’ Street, Suite 305 Lincoln, NE 68508 Phone: (402) 434-8585 Fax: (402) 436-3053 Celebrating15Yearsof reaching new goals and www.dressagefoundation.org [email protected] turning dreams into realities! I receive calls and messages on a work – yet they aspire to something More About regular basis from riders who have more. A common theme among all The Dressage the goal to become a Century Club is that becoming a member of this Foundation... member. “If only I stay healthy... if special group was a new goal, a new only my horse is sound next year...” dream, which was realized. LOWELL BOOMER founded The Dressage These riders have set a In 2011 we celebrated Foundation in 1989, and new goal – they have a 15 years of honoring its Mission is “To cultivate new dream. It is never senior dressage riders and provide financial too late to accomplish and horses. It is amazing support for the advancement something big, as the to think that in 2012, we of dressage.” Simply stated, Century Club riders will reach another mile- the business of The Dressage Foundation is featured in this issue stone – our 100th mem- to raise money, manage it, show us. -

2020 Western Dressage Rules

CHAPTER WD WESTERN DRESSAGE SUBCHAPTER WD-1 WESTERN DRESSAGE HORSE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES WD101 Goals and Objectives WD102 Participation in Western Dressage Competitions SUBCHAPTER WD-2 GAITS WD103 The Walk WD104 The Jog WD105 The Lope WD106 Saddle Gait WD107 The Back WD108 Faults SUBCHAPTER WD-3 ADDITIONAL MOVEMENTS AND METHODS WD109 The Halt WD110 Transitions WD111 Changes of Direction WD112 Figures and Exercises WD113 Work on Two Tracks and the Lateral Movements WD114 Turn on the Haunches: Turn on the Forehand WD115 Pirouette, Half Pirouette, and Quarter Pirouette at the Lope SUBCHAPTER WD-4 - COLLECTION, WILLING COOPERATION, IMPULSION, AIDS WD116 Collection WD117 Impulsion WD118 Willing Cooperation and Harmony WD119 Position and Aids of the Rider SUBCHAPTER WD-5 APPOINTMENTS WD120 General WD121 Tack WD122 Illegal Equipment WD123 Attire SUBCHAPTER WD-6 OFFICIALS WD124 Judges and Stewards SUBCHAPTER WD-7 COMPETITION REQUIREMENTS WD125 Warm Up Ring and Training Area WD126 Execution and Judging of Tests WD127 Scoring, Classification and Prize-Giving WD128 Elimination WD129 Requirements for Competition Management SUBCHAPTER WD-8 TESTS WD130 General © USEF 2020 1179 SUBCHAPTER WD-9 FREESTYLE WD131 Western Musical Freestyle SUBCHAPTER WD-10 DRESSAGE SUITABILITY WD132 General WD133 Appointments WD134 Qualifying Gaits WD135 Western Dressage Suitability Objectives WD136 Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER WD-11 DRESSAGE HACK WD137 General WD138 Appointments WD139 Qualifying Gaits WD140 Dressage Hack Objectives WD141 Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER WD-12 WESTERN DRESSAGE SEAT EQUITATION WD142 General Performance Directives for Western Dressage Equitation WD143 Western Dressage Seat Horsemanship WD144 Western Dressage Seat on the Rail WD145 Western Dressage Medal APPENDIX A EQUITATION PATTERNS 1180 © USEF 2020 CHAPTER WD WESTERN DRESSAGE When a subject is not addressed in these rules, it must be addressed by the committee and that committee’s interpre- tation will stand as the rule until the next year when an appropriate rule change will be submitted. -

2.11.2015, 'R' EV Judge PROCEDURES For

PROCEDURES for RECORDED ‘r’ EVENTING JUDGE LICENSE Listed below are the procedures required for recorded ‘r’ licensure as an Eventing judge. Consult GR1052 in Chapter 10 of the USEF Rules for a full description. Questions about licensure should be directed to the Licensed Officials Department through the following email address: [email protected]. TRAINING PROGRAM – Training Program requirements must be completed in the three years prior to application (See descriptions on Page three.) Training Sessions - The Training Sessions are administered by the U.S. Eventing Association. Information is available on USEA’s website www.useventing.com or from the USEA Director of Education, 525 Old Waterford Road NW, Leesburg, VA 20176 (703) 669-9997. In addition to the Independent Study and apprenticing requirements outlined on page three, applicants for the recorded ‘r’ Eventing Judge license must complete: • Dressage sections A and B; • Cross Country and Jumping Sections; and the • Final Examination. Exceptions: • Licensed Dressage Judges must complete the Cross Country and Jumping Training Programs. • USDF “L” Graduates must complete the apprenticeship requirements of the Dressage Training Program, as well as the entire Cross Country and Jumping Training Programs. • Licensed Eventing TDs must complete the Dressage Training Program. • Licensed Jumper Judges must complete the Cross Country and Dressage Training Programs. LICENSE REQUIREMENTS – The following requirements must be met before submitting an application. • In accordance with GR1004.2, you must be at least 21 years of age and a Senior active member in good standing of USEF. In addition, applicants must accumulate a minimum of 10 points from Riding, Organizational, and/or Officiating Experience: • Verifiable Riding Experience – To be counted, a ride must have achieved a Qualifying result and be from the past 15 years or otherwise verifiable. -

Section E – Dressage and Para-Dressage

SECTION E DRESSAGE AND PARA-DRESSAGE Rules of Equestrian Canada 2021 CHANGES VISIBLE EDITION This document illustrates all changes following the final 2020 edition. Changes are noted with additions underlined in red ink; deletions presented by strikethrough text, also in red. EQUESTRIAN CANADA RULEBOOK The rules published herein are effective on January 1, 2020 2021 and remain in effect for one year except as superseded by rule changes or clarifications published in subsequent editions of this section. Section E as printed herein is the official version of The Equestrian Canada Rules for Dressage and Para- Dressage for 20202021. The Rule Book comprises the following sections: A General Regulations B Breeds C Driving and Para-Driving D Eventing E Dressage and Para-Dressage F General Performance, Western, Equitation G Hunter, Jumper, Equitation and Hack J Endurance K Reining and Para-Reining L Vaulting Section E: DRESSAGE AND PARA-DRESSAGE is part of the Rulebook of Equestrian Canada and is published by: Equestrian Canada 11 Hines Rd., Suite 201308 Legget Drive, Suite 100 Ottawa, Ontario K2K 2X1K2K 1Y6 Tel: (613) 287-1515; Fax: (613) 248-3484 1-866-282-8395 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.equestrian.ca © 2021 Equestrian Canada 978-1-77288-105-9 EQUESTRIAN CANADA RULE BOOK SECTION E – DRESSAGE AND PARA-DRESSAGE These Rules are to be used in conjunction with the General Regulations of Equestrian Canada. TABLE OF CONTENTS The Equestrian Canada Rulebook ................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 Objects & Principles .................................................................... 2 Chapter 2 National Movements & Requirements ....................................... 21 Chapter 3 General ....................................................................................... 23 Chapter 4 Dress, Saddlery and Equipment ................................................ -

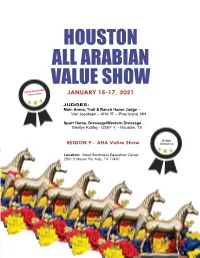

Houston All Arabian Value Show Follow the Class Numbers

HOUSTON ALL ARABIAN VALUE SHOW JANUARY 15-17, 2021 JUDGES: Main Arena, Trail & Ranch Horse Judge – Van Jacobsen – AHA ‘R’ – Pine Island, MN Sport Horse, Dressage/Western Dressage – Marilyn Kulifay - USEF ‘r’ – Houston, TX Multiple REGION 9 – AHA Value Show Disciplines Location: Great Southwest Equestrian Center 2501 S Mason Rd, Katy, TX 77450 *Exception: Sport Horse & Dressage SHOW OFFICIALS & STAFF Main Arena, Trail & Ranch Horse Judge VAN JACOBSEN – AHA “R” judge Sport Horse, Dressage / Western Dressage Judge MARILYN KULIFAY – USEF Licensed “r” SHOW SECRETARY PATTY LIARAKOS 210-912-8679 • [email protected] Assistant Secretary: Edythe Snowden Entry Deadline 12/28/2020 • Post Entries Accepted Manager/Barn Manager/Safety: Karen Blankenship……[email protected] 281-804-7791 Sport Horse & Dressage Manager: Debbie Cinotto….... [email protected] 817-319-9815 Photographer: Don Stine ........................................... [email protected] 832-289-2250 Announcer/Music: Nancy [email protected] 713-682-6803 Ring Master: Tony Lang ...................................................... [email protected] 832-229-0523 Farrier: Josh Parrish .....................................................joshparish77@aol.com 281-433-2819 Paddock Master: Doug Sullins ……………………………………………................. 979-218-0899 Gates: Ginny Vickers…………………………………………………………………………... 713-725-8028 Veterinarian: Decillo Equine of Hempstead (on call; not at show) …………… 979-826-2852 Security: Dave Wilson……………………………………………………………………….. -

Scottsdale Arabian Horse Show Draft Schedule for 2017

Scottsdale Arabian Horse Show February 16-26, 2017 Draft Schedule For 2017 Will be displayed online until August 19, 2016 for exhibitor comments Please email all suggestions for change to [email protected] Actual schedule will be posted online the first week of September after that time no classes will be added or moved. THURSDAY, February 16, 2017 THURSDAY MORNING - Equidome Arena - 8:00 A.M. Class # AHA # Class Title Judges Fee 1a 299 Arabian Hunter Pleasure JTR 15-18 (Possible Split) Panel 3 $25 2 890 Half-Arabian/Anglo-Arabian Hunter Pleasure JTR Walk/Trot 10 & Under Panel 4 $25 3 629 Half-Arabian/Anglo-Arabian Western Pleasure JTR 15-18 Panel 3 $25 4 517 Half-Arabian/Anglo-Arabian English Pleasure JOTR 18 & Under Panel 3 $25 5 629 Half-Arabian/Anglo-Arabian Western Pleasure JTR 14 & Under Panel 3 $25 6 890 Arabian Hunter Pleasure JTR Walk/Trot 10 & Under Panel 4 $25 7 549 Half-Arabian/Anglo-Arabian Country English Pleasure JTR 14 & Under Panel 4 $25 8a 104 Arabian Country English Pleasure JTR 15-18 (Possible Split) Panel 4 $25 9a 299 Arabian Hunter Pleasure JTR 14 & Under (Possible Split) Panel 3 $25 10 907 Arabian Western Seat Equitation JTR Walk/Trot 10 & Under Panel 4 $25 11 610 Half-Arabian/Anglo-Arabian Ladies Side Saddle Western JTR 18 & Under Panel 3 $25 THURSDAY MORNING - Wendell Arena - 8:00 A.M. Class # Class Title Judges Fee 1000 - Scottsdale Arabian Classic Geldings 3 Years & Under JTH Halter 1 $25 1001 - Scottsdale Arabian Classic Geldings 4 Years & Older JTH Halter 1 $25 1002 - Scottsdale Arabian Classic Gelding -

Chapter Dr Dressage Division Subchapter Dr-1

CHAPTER DR DRESSAGE DIVISION SUBCHAPTER DR-1 DRESSAGE GOVERNING REGULATIONS DR101 Object and General Principles of Dressage DR102 The Halt DR103 The Walk DR104 The Trot DR105 The Canter DR106 The Rein Back DR107 The Transitions DR108 The Half-Halt DR109 The Changes of Direction DR110 The Figures and The Exercises DR111 Work on Two Tracks and The Lateral Movements DR112 The Pirouette, The Half-pirouette, The Quarter-pirouette, The Working Pirouette, The Working Half- pirouette, The Turn on the Haunches DR113 The Passage DR114 The Piaffe DR115 The Collection DR116 The Impulsion, The Submission (Willing Cooperation) DR117 The Position and Aids of the Rider DR118 Tests for Dressage Competitions DR119 Participation in Dressage Competitions DR120 Dress DR121 Saddlery and Equipment DR122 Execution and Judging of Tests DR123 Scoring, Classification and Prize-Giving DR124 Elimination DR125 Competition Licensing and Officials DR126 Requirements for Dressage Competition Management SPECIAL COMPETITIONS DR127 USEF/USDF Qualifying and Championship Classes and USEF/USDF National Championships for Dressage DR128 USEF National Championships DR129 Musical Freestyle Ride DR130 Quadrille and Pas de Deux DR131 Dressage Derby DR132 Suitable to Become a Dressage Horse DR133 Dressage Seat Equitation © USEF 2021 DR - 1 DR134 Materiale Class DR135 Pony Measurement DR136 Exhibition (Class or Demonstration) DR137 Maiden, Novice, and Limit Classes. SUBCHAPTER DR-2 DRESSAGE SPORT HORSE BREEDING DR201 Purpose DR202 General Regulations DR203 Definitions DR204 Classes DR205 Entries DR206 Equipment and Turn Out DR207 General DR208 Competition Veterinarian DR209 Conduct of Classes DR210 Judging Specifications DR211 Judging Procedures SUBCHAPTER DR-3 PARA DRESSAGE DR301 Object of Para Dressage (PE) DR302 Position of the Athlete: DR303 Para Dressage Tests. -

CAWDA Talks with Joyce Swanson

CAWDA Talks with Joyce Swanson Joyce Swanson, Western Dressage Association Advisor and Licensed WDAA/USEF Judge, answers some questions for CAWDA members about what Western Dressage has to offer riders, where the sport is heading, and about her upcoming talk at the Los Angeles Equestrian Center. Hi Joyce, thank you for doing this interview! I read that you competed in Morgan Horse shows, where there have been Western Dressage classes for quite a while now. What made you think that Western riders of other breeds might be interested in the sport as well? Western Dressage was never meant to be breed specific because it is a performance discipline dependent more on conformation and suitability than a particular breed. Many of the founding members owned Morgan horses and their relationship with AMHA led to the Morgan division developing the first rules, tests and guidelines for judging. In 2010 WDAA was incorporated in the state of Colorado and reached out to all breeds and riders with robust educational programs like “Train the Trainers”™. Our mission statement to “honor the horse and value the partnership it has provided us on our American journey” attracted so many like-minded equestrians from all over the world. We had twenty-two breeds represented at our 2014 World Championship show and close to 40 state affiliates! What benefits does Western Dressage offer to riders who primarily participate in other disciplines, such as reining, competitive trail/extreme obstacle, or versatility? The concept of Western Dressage was embraced by numerous horsemen years ago. Many of us have been influenced by the surge of educational dressage programs developed with the founding of USDF in 1973 and we carried that knowledge into our chosen equestrian concentrations. -

Heart of the Carolinas

2016 HEART OF THE CAROLINAS Table of Contents Welcome Letter………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Event Schedule…………………………………………………….……………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Facility Map………………………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………………………..5 Officials, Staff, and Clinicians………………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………………………6 Team Bios……………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Course Maps..………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………………………………………………12 Sponsors………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………………………………………………17 Media Partners………………………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………………….18 Volunteers………………………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………………………………………19 Eventing Explained……………………………………………………………….………………………………………………………………………………….20 Area Map and Dining…………………………………………………………….………………………………………………………………………………...23 Guide to Safe Spectating………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….24 Cover photo: 2015 competitor Alanna Regan and Rupert; by Brant Gamma Photography 2 A Welcome From Your Hosts Welcome All, We are glad you could join us for the sixth anniversary of the Heart of the Carolina’s 3-Day Long Format and Horse Trials. There is no other equestrian event that requires as much discipline, conditioning, teamwork and heart, from both horse and rider, as the Long Format does. We are proud to be the only venue in the world that provides the opportunity for all levels of riders to experience the traditional form of Eventing. This past year has been especially productive