Elseya Albagula)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

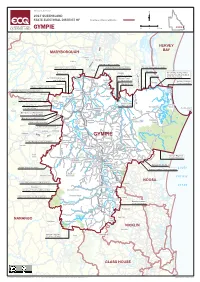

GYMPIE GYMPIE 0 5 10 Km

Electoral Act 1992 N 2017 QUEENSLAND STATE ELECTORAL DISTRICT OF Boundary of Electoral District GYMPIE GYMPIE 0 5 10 km HERVEY Y W H BAY MARYBOROUGH Pioneers Rest Owanyilla St Mary E C U Bauple locality boundary R Netherby locality boundary B Talegalla Weir locality boundary Tin Can Bay locality boundary Tiaro Mosquito Ck Barong Creek T Neerdie M Tin Can Bay locality meets in A a n locality boundary R Tinnanbar locality and Great r a e Y Kauri Ck Riv Sandy Strait locality Lot 125 SP205635 and B Toolara Forest O Netherby Lot 19 LX1269 Talegalla locality boundary R O Gympie Regional Weir U Tinnabar Council boundary Mount Urah Big Sandy Ck G H H Munna Creek locality boundary Bauple y r a T i n Inskip M Gundiah Gympie Regional Council boundary C r C Point C D C R e a Caloga e n Marodian k Gootchie O B Munna Creek Bauple Forest O Glenbar a L y NP Paterson O Glen Echo locality boundary A O Glen Echo G L Grongah O A O NP L Toolara Forest Lot 1 L371017 O Rainbow O locality boundary W Kanyan Tin Can Bay Beach Glenwood Double Island Lot 648 LX2014 Kanigan Tansey R Point Miva Neerdie D Wallu Glen Echo locality boundary Theebine Lot 85 LX604 E L UP Glen Echo locality boundary A RD B B B R Scotchy R Gunalda Cooloola U U Toolara Forest C Miva locality boundary Sexton Pocket C Cove E E Anderleigh Y Mudlo NP A Sexton locality boundary Kadina B Oakview Woolooga Cooloola M Kilkivan a WI r Curra DE Y HW y BA Y GYMPIE CAN Great Sandy NP Goomboorian Y A IN Lower Wonga locality boundary Lower Wonga Bells Corella T W Cinnabar Bridge Tamaree HW G Oakview G Y -

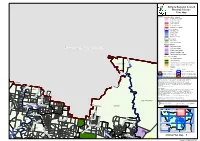

Gympie Regional Council Planning Scheme Zone Map Zoning Plan Map 4

Gympie Regional Council Planning Scheme Zone Map ZONES Residential zones category Character Residential Residential Living Rural Residential Residential Choice Tourist Accommodation Centre zones category Principal Centre District Centre Local Centre Specialised Centre Recreation category Open Space Sport and Recreation Industry category High Impact Industry Fraser Coast Regional Council Low Impact Industry Medium Impact Industry Industry Investigation area Waterfront and Marine Industry B I G Other zones category S A N Community Purposes D Y C Extractive Industry R E E K Environmental Management and Conservation TUAN FOREST Limited Development (Constrained Land) Township Rural Road TINA N Proposed Highway Zone Precinct Boundary A C ! ! R ! E ! EK DCDB ver. 05 June 2012 ! Suburb or Locality Boundary Waterbodies & Waterways Local Government Boundary Disclaimer While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this map, Gympie Regional Council makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, MUNNA CREEK MUNNA CREEK liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damage (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which might incur as a result of the data being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and D A K for any reason. O E R E © Copyright Gympie Regional Council 2012 C R S ULIRRAH EY L D Cadastre Disclaimer: L A U THEEBINE Despite Department of Environment and Resource Management (DERM)'s best efforts,DERM makes no A O representations or warranties in relation to the Information, and, to the extent permitted by law, C R exclude or limit all warranties relating to correctness, accuracy, reliability, completeness or currency E I and all liability for any direct, indirect and consequential costs, losses, damages and expenses incurred P in any way (including but not limited to that arising from negligence) in connection with any use of or M Y reliance on the Information. -

Land Valuations Overview: Gympie Regional Council

Land valuations overview: Gympie Regional Council On 31 March 2021, the Valuer-General released land valuations for 24,844 properties with a total value of $4,077,275,390 in the Gympie Regional Council area. The valuations reflect land values at 1 October 2020 and show that Gympie Regional Council has increased by 12.4 per cent overall since the last valuation in 2019. Residential, rural residential and primary production values have generally increased overall. Land values have generally increased since the last valuation, with some increases specific to certain market sectors and localities. Inspect the land valuation display listing View the valuation display listing for Gympie Regional Council online at www.qld.gov.au/landvaluation or visit the Department of Resources, 27 O'Connell Street, Gympie. Detailed valuation data for Gympie Regional Council Valuations were last issued in the Gympie Regional Council area in 2019. Property land use by total new value Residential land Table 1 below provides information on median values for residential land within the Gympie Regional Council area. Table 1 - Median value of residential land Residential Previous New median Change in Number of localities median value value as at median value properties as at 01/10/2020 (%) 01/10/2018 ($) ($) Amamoor 75,000 90,000 20.0 85 Araluen 123,000 135,000 9.8 9 Brooloo 69,000 83,000 20.3 60 Cinnabar 5,000 8,800 76.0 8 Cooloola Cove 84,000 92,000 9.5 1,685 Dagun 71,000 85,000 19.7 9 Goomeri 31,500 31,500 0.0 256 Gunalda 53,000 74,000 39.6 78 Gympie 87,000 96,000 -

Mary River Catchment Crawl 4 and 5 October 2016

Mary River Catchment Crawl 4th and 5th October 2016 Catchment crawl participants: Brad Wedlock, Caitlin Mill, Tanzi Smith, Jess Dean, Shaun Fisher, Ian Mackay, Ruth Hutchison, Matt Tattam, Kevin Jackson Introduction During the Mary River Month celebrations, the Mary River Catchment Coordinating Committee once again conducted its 8th annual Catchment Crawl on October 4th and 5th, 2016. The Catchment Crawls are designed to provide a snapshot of water quality along the Mary River. Water quality parameters are measured in an effort to gain insight to trends associated with cumulative effects and any other changes along the catchment area. On day one, testing begins in the upper reaches of the catchment, followed by a second day of testing in the lower reaches of the river and its tributaries, right out to the river mouth. A total of 14 freshwater sites were sampled along the main trunk of the Mary River, along with seven sites in several upper and lower tributaries for a total of 21 sites. The tributaries sampled include Six Mile Creek, Widgee Creek, Wide Bay Creek, Munna Creek and Tinana Creek. Sampling occurred across all three local government areas in the catchment. Figure 1 shows a map of all sites sampled during the 2016 catchment crawl. Creek junctions with the Mary River were targeted for sampling in order to gather information on the effects of tributaries flowing into the river. At each sampling site, a standard water test encompassing temperature, dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity, pH and turbidity was performed. In addition, a sample was taken at each site in accordance with DSITI protocol to be tested for nutrients and total suspended solids. -

Demographic Consequences of Superabundance in Krefft's River

i The comparative ecology of Krefft’s River Turtle Emydura krefftii in Tropical North Queensland. By Dane F. Trembath B.Sc. (Zoology) Applied Ecology Research Group University of Canberra ACT, 2601 Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Applied Science (Resource Management). August 2005. ii Abstract An ecological study was undertaken on four populations of Krefft’s River Turtle Emydura krefftii inhabiting the Townsville Area of Tropical North Queensland. Two sites were located in the Ross River, which runs through the urban areas of Townsville, and two sites were in rural areas at Alligator Creek and Stuart Creek (known as the Townsville Creeks). Earlier studies of the populations in Ross River had determined that the turtles existed at an exceptionally high density, that is, they were superabundant, and so the Townsville Creek sites were chosen as low abundance sites for comparison. The first aim of this study was to determine if there had been any demographic consequences caused by the abundance of turtle populations of the Ross River. Secondly, the project aimed to determine if the impoundments in the Ross River had affected the freshwater turtle fauna. Specifically this study aimed to determine if there were any difference between the growth, size at maturity, sexual dimorphism, size distribution, and diet of Emydura krefftii inhabiting two very different populations. A mark-recapture program estimated the turtle population sizes at between 490 and 5350 turtles per hectare. Most populations exhibited a predominant female sex-bias over the sampling period. Growth rates were rapid in juveniles but slowed once sexual maturity was attained; in males, growth basically stopped at maturity, but in females, growth continued post-maturity, although at a slower rate. -

Munna Creek Catchment Waterwatch Network Report 2010

Munna Creek Catchment Waterwatch Network Report 2010 - 2013 Report prepared by: Brad Wedlock & Steve Burgess MRCCC Catchment Officers October 2013 v2 This report prepared with the assistance of the Qld Government Everyone’s Environment Grant Disseminated August 2010 1 Introduction Many of the volunteers of the Munna Creek Waterwatch network have been collecting water quality data for more than 10 years which is providing the community, scientists and government agencies with a better understanding of the characteristics of the waterways in this part of the Mary River catchment. Without this committed volunteer effort we would not have access to this valuable information. This past year saw the boom-bust weather cycle continue. Between July 2012 and January 2013 the entire catchment experienced severe dry weather with virtually no rainfall recorded during this time with many creeks drying up. Then the late start to the wet season came with a bang on the Australia Day long weekend. The highest daily rainfall totals recorded at the peak of the rain event (27/1/13) in the Mary River catchment were located in the Munna Creek sub-catchment, with Brooweena recording 336mm and Marodian recording 347mm. This rainfall resulted in record levels of flooding in the upper and lower Munna Creek catchment. The Munna Creek Marodian gauging station broke the 1955 flood record by approximately ½ metre on the 27th January with a flood peak of 16.7m. The Wide Bay Creek catchment at Woolooga, broke the January 2011 flood peak record again by almost 1 metre with a flood peak of 13.87m. -

Queensland State School Reporting 2012 School Annual Report

T DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, TRAINING AND EMPLOYMENT Chatsworth State School (0915) Queensland State School Reporting 2012 School Annual Report YPEOVER TO INSERT SCHOOL NAME Postal address 15 Rammutt Road Chatsworth 4570 Phone (07) 5481 3777 Fax (07) 5481 3700 Email [email protected] Additional reporting information pertaining to Queensland state Webpages schools is located on the My School website and the Queensland Government data website. Contact Person Dianne Neumann Principal’s foreword Introduction I welcome you to our School Annual Report for 2012. This report provides a brief snapshot of our school data for 2012 and I encourage you to visit us at Chatsworth School for a personalised tour of our school to see firsthand the great learning environment we have established at our school. In this report we will outline our progress in relation to our 4 Year Strategic Plan as a National Partnership School. The data in this report relates to systemic data collected on the student population and performance, the school curriculum offerings, the school workforce and the whole school community’s opinions of the school. We also take the opportunity to highlight and celebrate our improvements and successes. Our data continues to demonstrate improvement in the majority of areas and highlights areas to focus on in future strategic plans. Chatsworth State School is in the North Coast Region, situated on the Northern outskirts of Gympie with picturesque views of the hills and valleys of surrounding rural areas. It is approximately 5 kilometres north of Gympie on the Bruce Highway and provides educational and social opportunities for the local rural communities of Chatsworth, Corella, Sexton, Tamaree, Old Maryborough Road, Harvey Siding, Gunalda, Glenwood, Lower Wonga, Bells Bridge, Curra and Two Mile. -

Mary River Environmental Values and Water Quality Objectives (Plan)

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! M A R Y R I V E R , I N C L U D I N G A L L T R I B U T A R I E S O F T H E R I V E! R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Basin 138 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 152°E 152°20'E ! 152°40'E 153°E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! H E R V E Y B AY ! ! ! B ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Grego R ! ! ry i ! ! v u er ! ! ! ! ! ! ! r ! ! ! ! CORDALBA ! n ! ! ! ! ! WALKERS ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! e ! ! ! POINT ! Environmental Protection (Water) Policy 2009 S ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! t ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! t t ! ! ! o ! ! Users must refer to plans WQ1372 k c ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! k ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! e ! y ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! R ! r e a and WQ1402 for information on South-east Queensland Map Series ! r ! i d ! ! C v BURRUM -

Register 2 0

© T E R R A R I S T I K - F A C H M A G A Z I N R E G I S T E R 2 0 1 0 1 REPTILIA-Register 2010 Terrarienpraxis 85, Oktober/November, 15(5): 38–45. BIRTEL, Andreas (2010): Ein Gewächshaus für Grüne Leguane und Pan- GEHRING, Philip-Sebastian, Maciej PABIJAN, Fanomezana M. RATSOAVI- therchamäleons. – Nr. 84, August/September 2010, 15(4): 44–45. NA, Jörn KÖHLER, Konrad MEBERT & Frank GLAW (2010): Calum- BRAUN, Sandra (2010): Bau eines naturnahen Schauterrariums für ein ma tarzan. Eine neue Chamäleonart aus Madaskar braucht dringend Jemenchamäleon. – Nr. 84, August/September 2010, 15(4): 40–43. Hilfe! – Nr. 86, Dezember 2010/Januar 2011, 15(6): 60–64. FRÖMBERG, Carsten (2010): Gestaltung von Verstecken unter Nutzung GUTSCHE, Alexander (2010): Mehrere Amphibien- und Reptilienarten von Latex-Bindemittel. – Nr. 84, August/September 2010, 15(4): neu in das Washingtoner Artenschutzabkommen (CITES) aufge- 36–38. nommen. – Nr. 83, Juni/Juli 2010, 15(3): 3–8. LONGHITANO, Filip (2010): Vorteile der Rackhaltung. – Nr. 84, August/ JACHAN, Georg (2010): Pfl ege und Vermehrung der Usambara-Busch- September 2010, 15(4): 34–35. viper Atheris ceratophora. – Nr. 83, Juni/Juli 2010, 15(3): 58–68. SCHLÜTER, Uwe (2010): Ernährung nord- und westafrikanischer Wara- KOCH, André (2010): Bestialische Behandlung indonesischer Großrep- ne in der Natur und bei Terrarienhaltung. – Nr. 86, Dezember 2010/ tilien für westliche Luxusprodukte. – Nr. 86, Dezember 2010/Januar Januar 2011, 15(6): 36–45. 2011, 15(6): 3–6. SCHMIDT, Dieter (2010): Naturterrarium oder Heimtierkäfi g? – Nr. 84, KOCH, Claudia (2010): Geheimnisvolles Peru. -

Recent Evolutionary History of the Australian Freshwater Turtles Chelodina Expansa and Chelodina Longicollis

Recent evolutionary history of the Australian freshwater turtles Chelodina expansa and Chelodina longicollis. by Kate Meredith Hodges B.Sc. (Hons) ANU, 2004 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences Department of Genetics and Evolution The University of Adelaide December, 2015 Kate Hodges with Chelodina (Macrochelodina) expansa from upper River Murray. Photo by David Thorpe, Border Mail. i Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. The author acknowledges that copyright of published works contained within this thesis resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library catalogue and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. -

Project Section D

Bruce Highway (Cooroy to Curra) Project Section D Terrestrial Fauna Survey Report (Final) Department of Transport and Main Roads May 2016 0331161 www.erm.com The world’s leading sustainability consultancy Bruce Highway (Cooroy to Curra) Approved by: Tom Cotter Project Section D Position: Project Manager Terrestrial Fauna Survey Report (Final) Signed: Department of Transport and Main Roads Date: 13 May, 2016 Approved by: David Dique May 2016 Position: Partner Signed: Date: 13 May, 2016 0331161 www.erm.com Environmental Resources Management Australia Pty Ltd Quality System This disclaimer, together with any limitations specified in the report, apply to use of this report. This report was prepared in accordance with the contracted scope of services for the specific purpose stated and subject to the applicable cost, time and other constraints. In preparing this report, ERM relied on: (a) client/third party information which was not verified by ERM except to the extent required by the scope of services, and ERM does not accept responsibility for omissions or inaccuracies in the client/third party information; and (b) information taken at or under the particular times and conditions specified, and ERM does not accept responsibility for any subsequent changes. This report has been prepared solely for use by, and is confidential to, the client and ERM accepts no responsibility for its use by other persons. This report is subject to copyright protection and the copyright owner reserves its rights. This report does not constitute legal advice. -

Resolving the Phylogenetic History of the Short-Necked Turtles, Genera

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 68 (2013) 251–258 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Resolving the phylogenetic history of the short-necked turtles, genera Elseya and Myuchelys (Testudines: Chelidae) from Australia and New Guinea ⇑ Minh Le a,b,c, , Brendan N. Reid d, William P. McCord e, Eugenia Naro-Maciel f, Christopher J. Raxworthy c, George Amato g, Arthur Georges h a Department of Environmental Ecology, Faculty of Environmental Science, Hanoi University of Science, VNU, 334 Nguyen Trai Road, Thanh Xuan District, Hanoi, Viet Nam b Centre for Natural Resources and Environmental Studies, VNU, 19 Le Thanh Tong Street, Hanoi, Viet Nam c Department of Herpetology, Division of Vertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA d Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, University of Wisconsin, 1630 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA e East Fishkill Animal Hospital, 455 Route 82, Hopewell Junction, NY 12533, USA f Biology Department, College of Staten Island, City University of New York, Staten Island, NY 10314, USA g Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA h Institute for Applied Ecology, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia article info abstract Article history: Phylogenetic relationships and taxonomy of the short-necked turtles of the genera Elseya, Myuchelys, and Received 15 October 2012 Emydura in Australia and New Guinea have long been debated as a result of conflicting hypotheses sup- Revised 14 March 2013 ported by different data sets and phylogenetic analyses. To resolve this contentious issue, we analyzed Accepted 24 March 2013 sequences from two mitochondrial genes (cytochrome b and ND4) and one nuclear intron gene (R35) from Available online 4 April 2013 all species of the genera Elseya, Myuchelys, Emydura, and their relatives.