Special Committee on Apartheid Begins Work for 1972

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLACK ISLAM SOUTH AFRICA Religious Territoriality, Conversion

BLACK ISLAM SOUTH AFRICA Religious Territoriality, Conversion, and the Transgression of Orderly Indigeneity Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Dr. phil. im Promotionsfach Geographie am Fachbereich Chemie, Pharmazie, Geographie und Geowissenschaften der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz vorgelegt von Matthias Gebauer geb. in Lichtenfels 2019 i Abstract Social alienation and the struggle to belong in the South African society are not only matters of political discourse but touch the practical sphere of everyday life in the respective places of residence. This thesis therefore approaches the entanglements of religion and space within the processes of re-ordering African indigeneity in post-apartheid South Africa. It asks how conversion to Islam constitutes the longing for a post-colonial and post-racialized African self. This study specifically engages with dynamics surrounding Black and Muslim practices and identity politics in formerly demarcated Black African areas. Here, even after the official end of apartheid, spatial racialization and social inequalities persist. Modes of orderings rooted in colonialism and apartheid still define what orderly belonging and African indigeneity mean. Thus, the inhabitants of those spaces find themselves in situations every day in which their habitat continuously ascribes oppression and racialization. The post-1994 promise for equal citizenship seems to be slowly fading, becoming a broken promise, on whose fulfillment the majority of people who were previously—by official definition and demarcation—only granted the right of being a migratory workforce, sojourners in the White spaces, are still waiting. Against this background, this thesis engages with the attempts to reformulate and recreate African indigeneity on the basis of a counter-hegemonic ideology of being Black and Muslim. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd Is Assassinated in the House of Assembly by a Parliamentary Messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd is assassinated in the House of Assembly by a parliamentary messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September. Balthazar J Vorster becomes Prime Minister on 13 September. 1967 The Terrorism Act is passed, in terms of which police are empowered to detain in solitary confinement for indefinite periods with no access to visitors. The public is not entitled to information relating to the identity and number of people detained. The Act is allegedly passed to deal with SWA/Namibian opposition and NP politicians assure Parliament it is not intended for local use. Besides being used to detain Toivo ya Toivo and other members of Ovambo People’s Organisation, the Act is used to detain South Africans. SAP counter-insurgency training begins (followed by similar SADF training in the following year). Compulsory military service for all white male youths is extended and all ex-servicemen become eligible for recall over a twenty-year period. Formation of the PAC armed wing, the Azanian Peoples Liberation Army (APLA). MK guerrillas conduct their first military actions with ZIPRA in north-western Rhodesia in campaigns known as Wankie and Sepolilo. In response, SAP units are deployed in Rhodesia. 1968 The Prohibition of Political Interference Act prohibits the formation and foreign financing of non-racial political parties. The Bureau of State Security (BOSS) is formed. BOSS operates independently of the police and is accountable to the Prime Minister. The PAC military wing attempts to reach South Africa through Botswana and Mozambique in what becomes known as the Villa Peri campaign. 1969 The ANC holds its first Consultative (Morogoro) Conference in Tanzania, and adopts the ‘Strategies and Tactics of the ANC’ programme, which includes its new approach to the ‘armed struggle’ and ‘political mobilisation’. -

Islamic Liberation Theology in South Africa: Farid Esack’S Religio-Political Thought

ISLAMIC LIBERATION THEOLOGY IN SOUTH AFRICA: FARID ESACK’S RELIGIO-POLITICAL THOUGHT Yusuf Enes Sezgin A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Cemil Aydin Susan Dabney Pennybacker Juliane Hammer ã2020 Yusuf Enes Sezgin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Yusuf Enes Sezgin: Islamic Liberation Theology in South Africa: Farid Esack’s Religio-Political Thought (Under the direction of Cemil Aydin) In this thesis, through analyzing the religiopolitical ideas of Farid Esack, I explore the local and global historical factors that made possible the emergence of Islamic liberation theology in South Africa. The study reveals how Esack defined and improved Islamic liberation theology in the South African context, how he converged with and diverged from the mainstream transnational Muslim political thought of the time, and how he engaged with Christian liberation theology. I argue that locating Islamic liberation theology within the debate on transnational Islamism of the 1970s onwards helps to explore the often-overlooked internal diversity of contemporary Muslim political thought. Moreover, it might provide important insights into the possible continuities between the emancipatory Muslim thought of the pre-1980s and Islamic liberation theology. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to many wonderful people who have helped me to move forward on my academic journey and provided generous support along the way. I would like to thank my teachers at Boğaziçi University from whom I learned so much. I was very lucky to take two great courses from Zeynep Kadirbeyoğlu whose classrooms and mentorship profoundly improved my research skills and made possible to discover my interests at an early stage. -

The Fifth Annual Imam Abdullah Haron Memorial Lecture

The Fifth Annual Imam Abdullah Haron Memorial Lecture “Has tolerance no limits?” Why the education crisis persists Jonathan D Jansen University of the Free State 2 October 2012 Introduction Two events of seismic proportions shook the Western Cape in the closing days of September 1969. The first was the Ceres-Tulbagh earthquake of 29 September which registered 6.3 on the Richter scale with aftershocks that continued as far forward as the 14th of April 1970 and whose effects were felt more than 1000 km away in Durban. The earthquake was said to have caused physical displacement of 26cm of ground over a distance of 20km, and that it was caused by “a shallow tectonic failure along the Saron- Groenhof lineament.”1 The second seismic shock was the murder on the night of 27 September in the Maitland police cells of the 44-year old Imam of the Stegman Street Mosque, the Editor of “Moslem News”, the husband of Galiema, and the father of three young children— Shamila, Mogamet and Fatima. That death—the 12th of a political prisoner to die in police custody between 1963 and 1969—sent forth tremors of grief and protest that registered shockwaves well beyond the borders of South Africa. The killing of the Imam displaced the political grounds in the Cape; indeed it shook complacent communities into political action for this noble martyr was killed by a shallow political and moral failure that was rightly laid at the door of the politicians (apartheid’s NP 1 Paragraph draws on http://www.stormchasing.co.za/articles-and-news/historic-weather-archive/184-tulbagh- ceres-1969-earthquake 1 parliamentarians) and their professional collaborators (lawyers, doctors, police) who tried to prop-up an immoral and racist system. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Identity Construction in Post-apartheid South Africa: the Case of the Muslim Community Rania Hassan PhD in African Studies The University of Edinburgh 2011 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................................................I ABSTRACT........................................................................................................................................III DECLARATION..................................................................................................................................V GLOSSARY....................................................................................................................................... -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal .............................................................. 528 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Transvaal ...................................................... -

Premier of the Western Cape – Ebrahim Rasool

Premier of the Western Cape – Ebrahim Rasool List of Honourees receiving Provincial Honours 2004 1. Commander of the Order of the Disa awarded to Nelson R. Mandela As a young man, hearing the elders’ stories of his ancestors’ valour during the wars of resistance in defence of their fatherland, Nelson Mandela dreamed also of making his own contribution to the freedom struggle of his people. He served articles at a law firm in Johannesburg where years of daily exposure to the inhumanities of apartheid, where being black reduced one to the status of a non-person, kindled in him a courage to change the world. On joining the Youth League of the African National Congress, Nelson Mandela became involved in programmes of passive resistance against apartheid’s denial of political, social and economic rights to South Africa’s black majority. In the revolution led by Mandela to transform a model of racial division and oppression into an open democracy, he demonstrated that he did not flinch in the face of adversity. As the world's most famous prisoner, leader, teacher and man, he exemplifies a moral integrity that shines far beyond South Africa. 2. Commander of the Order of the Disa awarded to F.W De Klerk When F.W de Klerk lifted the ban on the ANC and other organisations in 1990, he set in motion a new era of transformation in South Africa. This end to apartheid and South Africa’s racial segregation policy paved the way for negotiations, resulting in the release of Nelson Mandela and culminating in the first ever racially inclusive elections in South Africa in 1994. -

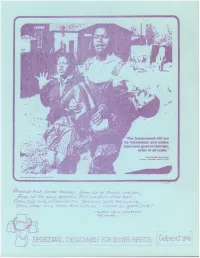

Be Intimidated, and Orders Have Been Given to Maintain Order at All Costs.,"

"The Government will not be Intimidated, and orders have been given to maintain order at all costs.," Prime Mm;stsr *Inv Vomter House of Assembly . Arn 1$, 1976. With ,, . .i... ;-I ,m —ai% :v-.: i :, at., /f.''.)e .,.,-- t,rt/'Pn. i.:/ij e f ::iir 3. ,:e, ) 4 ; ' E/ ,- ; Pty ) .. )'1_ "-, .5t, '‘%. 1r f 4 .7) ..*1 '/"A , .-.,. t ,7,~% :~" ~^'~i v ,:%'f!. =-fi:, d,::A. ,r?,,, 4 '':;,'' rit'.l 'E:K.7r" i T4-i SaTE RTC.1\1 r'') r,r- w't rte" 7-- 1 n 4-1 4, [AdcfEK; 19 . L., t L., Li 1-1 ,i , u T t L-I j SOWETO STUDENTS REPRESENTATIVE COUNCIL October 1976 TO : ALL FATHERS 3c MOTHERS, BROTHERS & SISTERS, FRIENDS & WORKERS, IN ALL CITIES, TOWNS & VILLAGES IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA: We appeal to you to align yourselves with the struggle for your own liberation. Be involved and be united with us as it is your own son and daughter that we bury every week-end . Death has become a common thing to us all in the town- ships . There is no peace, there shall be none until we are all free. I . Soweto and all Black townships are now going into a period of MOURNING for the dead . We are to pay respect to all students and adults murdered by the police. 2. We are to pledge our solidarity with those detained in police cells and are suffering torture on our behalf. 3. We should .show our' sympathy and support to all those workers who suffered reduction of wages and loss of jobs because they obeyed our call to stay away from work for three days. -

GENERAL ASSEMBLY FOURTH COMMITTEE, 1878Th

United Nations FOURTH COMMITTEE, 1878th GENERAL MEETING ASSEMBLY Friday, 9 October 1970, at 3.35 p.m. TWENTY-FIFTH SESSION Official Records NEW YORK Chairman: Mr. Vernon Johnson MWAANGA subjected to forcible removal from one place to another in (Zambia). order to provide room for the expansion of the European area. The means used for that purpose included deprivation of water and sanctions against sanitary arrangements. The In the absence of the Chairman, Mr. Sadry (Iran), new townships into which Africans were being squeezed Vice-Chairman, took the Chair. were tightly surrounded by barbed wire fences, with only one gate facing the city. Whenever they entered or left a township, residents were required to show twelve or more AGENDA ITEM 62 passes to the armed policemen stationed at the gate. The police had master keys which enabled them at any time of Question of Namibia (continued) the day or night to enter any premises in which they (A/8023/Add.2, A/C.4/127/Add.1 and 2) suspected an African of committing the criminal offence of allowing relatives or friends to stay with him for seventy HEARING OF PETITIONERS two hours. No African lawfully residing in a town by virtue of a permit issued to him was entitled to have his wife living 1. The CHAIRMAN recalled that at its 1875th and 1876th there with him. According to reliable sources, the death meetings the Committee had decided to grant a number of rate had tripled in the new townships as a result of requests for hearings concerning Namibia. -

An Example of Muslim Marriages in South Africa Waheeda Amien

Maryland Journal of International Law Volume 29 Issue 1 Symposium: "The International Law and Article 18 Politics of External Intervention in Internal Conflicts" and Special Issue: "Politics of Religious Freedom" Legislating Religious Freedom: An Example of Muslim Marriages in South Africa Waheeda Amien Dhammameghā Annie Leatt Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mjil Recommended Citation Waheeda Amien, & Dhammameghā A. Leatt, Legislating Religious Freedom: An Example of Muslim Marriages in South Africa, 29 Md. J. Int'l L. 505 (2014). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mjil/vol29/iss1/18 This Special Issue: Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE Legislating Religious Freedom: An Example of Muslim Marriages in South Africa † †† WAHEEDA AMIEN AND ANNIE LEATT (DHAMMAMEGHĀ) INTRODUCTION For the past 27 years, diverse groups of Muslims have lobbied for the legalization of Muslim marriages in South Africa and for the codification of elements of Muslim Personal Law (MPL). MPL is an Islamic-based private law system comprising family law and inheritance. Perhaps surprisingly, certain ulamā bodies (Muslim religious bodies or clergy)1 and gender activists have supported draft legislation for the recognition of Muslim marriages under the enabling provisions of the final Constitution of South Africa 1996, though for quite different reasons. Yet, despite successive proposals, widespread consultation within the Muslim community, and two draft Muslim marriage bills, Muslim marriages are still not recognized in South Africa. -

INTRODUCTION the Past, the TRC and the Archive As Depository Of

1 INTRODUCTION The Past, the TRC and the Archive as Depository of Memory Brent Harris At a lecture presented in London on June 5, 1994, Jacques Derrida discussed the complexities of the meaning of the archive. He described the duality in meaning of the word archive ─ in terms of temporality and spatiality ─ as a place of «commencement» and as the place «where men and gods command» or the «place from which order is given».1 As the place of commencement, «there where things commence»,2 the archive is more ambivalent. It houses, what could best be described as ‘traces’3 of particular objects of the past in the form of documents. These documents were produced in the past and are subjective constructions with their own histories of negotiations and contestations. As such, the archive represents the end of instability, or the outcome of negotiations and contestations over knowledge. Yet as sources of evidence the archive also represents the moment of ending instability, of creating stasis and the fixing of meaning and knowledge. The archive has long been the hallmark for, and of, the production of history, particularly in the academy. Students of history have been taught that to do research, they have to go to the archive to ‘read’ the primary sources located there. The process, in historical research, of discovering new areas of research had tended to close the past contained in the archive. For decades most 1Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1996, p. 1. Emphasis in original. 2Derrida, Archive Fever, p.