Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Joy Ladin from Through the Door of Life: a Jewish Journey Between Genders

Joy Ladin from Through the Door of Life: A Jewish Journey Between Genders “Why did you have to be a girl?” my youngest asks. It’s spring 2010, almost three years since I moved out. She’s naked and glistening in a bath whose bubbles are disappearing, surrounded by a flotilla of toys – plastic animals, a large submarine, a battered Barbie, an empty vitamin bottle – she alternately buries and resurrects from the fragrant white foam. Her disease has marked her face with a peculiar beauty, blending the cherubic features of a toddler with the serious lines and deep-set eyes of middle age. It’s slowed her physical growth, but so far it hasn’t damaged her brain, kidneys, or heart. She doesn’t realize it, but I look up to her: unlike me, she’s utterly, unapologetically delighted with herself, unscarred by her differences from others, so matter-of-fact in her determination to overcome her physical limitations that I’m not even sure she sees them as limitations. She doesn’t seem to measure herself against her larger, faster, stronger, defter peers. Her delight in herself is part and parcel with her boundless delight in existence. Despite the chromosomal glitches, she’s grown up a lot since I left my family. She’s no longer an inarticulate, uncritically loving three-year-old; at six, she has found words for what she’s lost. Whenever I see her – now it’s only twice a week – she grills me about the motives and morality of my transition. The subject first came up between us when she was five; we were at the tiny local public library, and we both needed to use the bathroom. -

Beyoncé Feminism, Rihanna Womanism: Popular Music and Black Feminist Theory AFR 330, WGS 335 Flags: Cultural Diversity in the US, Global Cultures Spring 2020

The University of Texas at Austin Beyoncé Feminism, Rihanna Womanism: Popular Music and Black Feminist Theory AFR 330, WGS 335 Flags: Cultural Diversity in the US, Global Cultures Spring 2020 Prof: Dr. Traci-Ann Wint Course Description Beyoncé’s fifth live album Homecoming chronicled her performance as the first black woman to headline the Coachella festival. As with Lemonade, the film and performance put Beyoncé’s music in conversation with luminaries such as Toni Morrison and W.E.B. DuBois. Beyoncé’s contemporaries Rihanna and Lizzo similarly center black culture in their music and are unapologetic about their work’s engagement with issues specific to black womanhood. By engaging the music and videos of these and other Black femme recording artists as popular, accessible expressions of African American and Caribbean feminisms, this course explores their contribution to black feminist thought and their impact on global audiences. Beginning with close analysis of these artists’ songs and videos, we read their work in conversation with black feminist theoretical works that engage issues of race, location, violence, economic opportunity, sexuality, standards of beauty, and creative self-expression. The course aims to provide students with an introduction to media studies methodology as well as black feminist theory, and to challenge us to close the gap between popular and academic expressions of black women’s concerns. Course Goals The course aims to provide students with an introduction to Black feminism, Black feminist thought and womanism through an examination of popular culture. At the end of the course students should have a firm grasp on Black Feminist and Womanist theory, techniques in pop culture and media analysis and should be comfortable with the production of scholarly work for a popular audience. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

NO ME WITHOUT YOU Thesis Submitted to the College of Arts

NO ME WITHOUT YOU Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in English By Sandra E. Riley, M.Ed UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2017 NO ME WITHOUT YOU Name: Riley, Sandra Elizabeth APPROVED BY: ____________________________________ PJ Carlisle, Ph.D Advisor, H.W. Martin Post Doc Fellow ____________________________________ Andrew Slade, Ph.D Department Chair, Reader #1 ____________________________________ Bryan Bardine, Ph.D Associate Professor of English, Reader #2 ii ABSTRACT NO ME WITHOUT YOU Name: Riley, Sandra Elizabeth University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. PJ Carlisle This novel is an exploration of the narrator‟s grief as she undertakes a quest to understand the reasons for her sister‟s suicide. Through this grieving process, the heroine must confront old family traumas and negotiate ways of coping with these ugly truths. It is a novel about family secrets, trauma, addiction, mental illness, and ultimately, resilience. iii Dedicated to JLH iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my earliest reader at the University of Dayton—Dr. Meredith Doench, whose encouragement compelled me to keep writing, despite early frustrations in the drafting process. Thank you to Professor Al Carrillo—our initial conversations gave me the courage to keep writing, and convinced me that I did in fact have the makings of a novel. Thank you to Dr. Andy Slade, who has been gracious and accommodating throughout my journey to the MA, and to Dr. PJ Carlisle, who not only agreed to be my thesis advisor her last semester at UD, but gave me the direction and input I needed while understanding my vision for No Me Without You. -

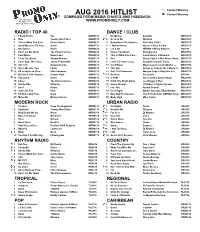

AUG 2016 HITLIST Content Warning COMPILED from MEDIA CHARTS and FEEDBACK the Industry's #1 Source for Music & Music Video

Content Warning AUG 2016 HITLIST Content Warning COMPILED FROM MEDIA CHARTS AND FEEDBACK The Industry's #1 Source For WWW.PROMOONLY.COM Music & Music Video RADIO / TOP 40 DANCE / CLUB 1 Cheap Thrills Sia MSR0416 1 No Money Galantis MSC0816 2 Ride Twenty One Pilots MSR0516 2 Needed Me Rihanna MSC0816 3 This Is What You Cam... Calvin Harris MSR0616 3 Bring Back The Summe... Rain Man f./OLY MSC0716 4 Send My Love (To You... Adele MSR0716 4 I Wanna Know Alesso f./Nico & Vinz MSC0716 5 One Dance Drake MSR0516 5 Let It Go NERVO f./Nicky Romero RC0716 6 Don't Let Me Down The Chainsmokers MSR0416 6 Chase You Down Runaground MSC0516 7 Cold Water Major Lazer MSR0916 7 This Is What You Cam... Calvin Harris f./Rihanna MSC0816 8 Treat You Better Shawn Mendes MSR0716 8 Sex Cheat Codes x Kris Kross Amst... MSC0716 9 Can't Stop The Feeli... Justin Timberlake MSR0616 9 Livin' For Your Love... Rosabel f./Jeanie Tracy MSC0616 10 Into You Ariana Grande MSR0816 10 Cold Water Major Lazer f./Justin Bieber ... MSC0916 11 Never Be Like You Flume MSR0516 11 This Girl Kungs vs Cookin' On 3 Burners MSC0816 12 All In My Head (Flex... Fifth Harmony MSR0716 12 Safe Till Tomorrow Morgan Page f./Angelika Vee MSC0716 13 We Don't Talk Anymor... Charlie Puth MSR0716 13 Bonbon Era Istrefi RC0816 14 Too Good Drake MSR0816 14 ILYSM Steve Aoki & Autoerotique MSC0916 15 Closer The Chainsmokers MSR0916 15 Drink The Night Away Lee Dagger f./Bex MSC0616 16 Needed Me Rihanna MSR0816 16 Sweet Dreams JX Riders f./Skylar Stecker MSC0916 17 Gold Kiiara MSR0716 17 Into You Ariana Grande MSC0816 18 Just Like Fire Pink MSR0816 18 Do It Right Martin Solveig f./Tkay Maidza MSC0816 19 Sit Still, Look Pret.. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Live Exchange Party Band Song List

Live Exchange Party Band Song List FUNK Uptown Funk-Bruno Mars Let's groove-EWF September-EWF Before I let go-maze I'll be around- Spinners That's the way- KC in the sunshine band Brick House- commodores Jamaica Funk-Tom Browne Da Butt- EU Ain't nobody- Chaka Khan Tell Me something good- Chaka Khan Candy- cameo Boogie Shoes-KC and the sunshine band Ladies night- Kool and the Gang Boogie Oogie- A taste of Honey Play that funky music- wild Cherry Superstition-Stevie Wonder Sign sealed delivered- Stevie Wonder Best of my Love-The Emotions To be real-Cheryl Lynn Funky town- Lipps INC Funky good time- James Brown Get up-James Brown I feel good-James Brown Bird- Morris Day and the Time Get down on it- Kool and the gang Drop The bomb- The Gap Band Give it to me Baby- Rick James Word up-Cameo Jungle love The bird Teena Marie - Square Biz Gap Band - Early in the morning Midnight Star - No parking on the dance Floor MJ - Dancing Machine Morris Day - Jungle Love RAP Snap your fingers-Lil John About the money- T.I. All I do is win- Dj Alright- Kendrick Lamar Summertime- Dj Jazzy Jeff & the fresh Prince Whip and Nae Nae-Silentó Hotline Bling- Drake California- Ricco Barrino Better have my money-Rihanna Hey ya- Outkast R&B Love Changes- mothers finest Tyrone-Erykah Badu On&On-Erykah Badu Just Friends-Musiq The way-Jill Scott He loves me-Jill Scott Between the sheets-Isley Brothers Foot steps in the dark-Isley Brothers Sweet thing-Chaka Khan Stay with me- Sam Smith All of Me- John legend Do for love- Bobby Caldwell Just the two of us-Bill Withers Dock