Atlantic Yellow-Nosed Albatross EN1.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic Ocean

Appendix B – Region 18 Country and regional profiles of volcanic hazard and risk: Atlantic Ocean S.K. Brown1, R.S.J. Sparks1, K. Mee2, C. Vye-Brown2, E.Ilyinskaya2, S.F. Jenkins1, S.C. Loughlin2* 1University of Bristol, UK; 2British Geological Survey, UK, * Full contributor list available in Appendix B Full Download This download comprises the profiles for Region 18: Atlantic Ocean only. For the full report and all regions see Appendix B Full Download. Page numbers reflect position in the full report. The following countries are profiled here: Region 18 Atlantic Ocean Pg.743 Brazil 750 Cape Verde 754 Portugal – Azores 761 Spain – Canary Islands 767 UK – Tristan da Cunha, Nightingale Island, Ascension 775 Brown, S.K., Sparks, R.S.J., Mee, K., Vye-Brown, C., Ilyinskaya, E., Jenkins, S.F., and Loughlin, S.C. (2015) Country and regional profiles of volcanic hazard and risk. In: S.C. Loughlin, R.S.J. Sparks, S.K. Brown, S.F. Jenkins & C. Vye-Brown (eds) Global Volcanic Hazards and Risk, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. This profile and the data therein should not be used in place of focussed assessments and information provided by local monitoring and research institutions. Region 18: Atlantic Ocean Figure 18.1 The distribution of Holocene volcanoes through the Atlantic Ocean region. The capital cities of the constituent countries are shown. The host countries are identified on the right. Description Region 18: the Atlantic Ocean comprises volcanoes throughout the Atlantic, from an unnamed seamount in the north to the Norwegian territory of Bouvet in the south. Six countries are represented here. -

S41467-020-18361-4.Pdf

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18361-4 OPEN Seafloor evidence for pre-shield volcanism above the Tristan da Cunha mantle plume ✉ Wolfram H. Geissler 1 , Paul Wintersteller 2,3, Marcia Maia4, Anne Strack3, Janina Kammann5, Graeme Eagles 1, Marion Jegen6, Antje Schloemer1,7 & Wilfried Jokat 1,2 Tristan da Cunha is assumed to be the youngest subaerial expression of the Walvis Ridge hot spot. Based on new hydroacoustic data, we propose that the most recent hot spot volcanic 1234567890():,; activity occurs west of the island. We surveyed relatively young intraplate volcanic fields and scattered, probably monogenetic, submarine volcanoes with multibeam echosounders and sub-bottom profilers. Structural and zonal GIS analysis of bathymetric and backscatter results, based on habitat mapping algorithms to discriminate seafloor features, revealed numerous previously-unknown volcanic structures. South of Tristan da Cunha, we discovered two large seamounts. One of them, Isolde Seamount, is most likely the source of a 2004 submarine eruption known from a pumice stranding event and seismological analysis. An oceanic core complex, identified at the intersection of the Tristan da Cunha Transform and Fracture Zone System with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, might indicate reduced magma supply and, therefore, weak plume-ridge interaction at present times. 1 Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Am Alten Hafen 26, 27568 Bremerhaven, Germany. 2 Faculty of Geosciences, University of Bremen, Klagenfurter Str. 4, 28359 Bremen, Germany. 3 MARUM—Center of Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Leobener Str. 8, 28359 Bremen, Germany. 4 CNRS-UBO Laboratoire Domaines Océaniques, Institut Universitaire Européen de la Mer, 29280 Plouzané, France. -

Beetles of the Tristan Da Cunha Islands

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Koleopterologische Rundschau Jahr/Year: 2013 Band/Volume: 83_2013 Autor(en)/Author(s): Hänel Christine, Jäch Manfred A. Artikel/Article: Beetles of the Tristan da Cunha Islands: Poignant new findings, and checklist of the archipelagos species, mapping an exponential increase in alien composition (Coleoptera). 257-282 ©Wiener Coleopterologenverein (WCV), download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Koleopterologische Rundschau 83 257–282 Wien, September 2013 Beetles of the Tristan da Cunha Islands: Dr. Hildegard Winkler Poignant new findings, and checklist of the archipelagos species, mapping an exponential Fachgeschäft & Buchhandlung für Entomologie increase in alien composition (Coleoptera) C. HÄNEL & M.A. JÄCH Abstract Results of a Coleoptera collection from the Tristan da Cunha Islands (Tristan and Nightingale) made in 2005 are presented, revealing 16 new records: Eleven species from eight families are new records for Tristan Island, and five species from four families are new records for Nightingale Island. Two families (Anthribidae, Corylophidae), five genera (Bisnius STEPHENS, Bledius LEACH, Homoe- odera WOLLASTON, Micrambe THOMSON, Sericoderus STEPHENS) and seven species Homoeodera pumilio WOLLASTON, 1877 (Anthribidae), Sericoderus sp. (Corylophidae), Micrambe gracilipes WOLLASTON, 1871 (Cryptophagidae), Cryptolestes ferrugineus (STEPHENS, 1831) (Laemophloeidae), Cartodere ? constricta (GYLLENHAL, -

Recruitment of a Medical Officer on Tristan Da Cunha

RECRUITMENT OF A MEDICAL OFFICER ON TRISTAN DA CUNHA Information Pack - 1 - Tristan da Cunha Information Pack: Medical Officer Contents Job Description ........................................................................................ 3 Tristan da cunha health policy .................................................................. 9 Country briefing notes ............................................................................ 18 TRISTAN DA CUNHA GOVERNMENT JOB DESCRIPTION Role: Medical Officer, Tristan da Cunha Accountable to: Reports to: Island Administrator Essential Qualifications: Full registration with the General Medical Council (GMC) or similar Medical Board. MB/BM/BS/BAO/BCH ACLS, PALS (APLS) and ATLS Essential Experience: Primary Health Care Demonstrated experience in General Surgery Demonstrated experience in Anaesthetics – including experience of providing dissociation anaesthesia Demonstrated experience in Obstetrics and the ability to manage deliveries single handed (normal and caesarean) Desirable Qualifications A higher medical qualification in either obstetrics or surgery would be beneficial. Desirable Experience: Experience in Public Health and / or Health Services Management Experience in motivating and leading a team to achieve organisational goals Duration of assignment 1 year post with possibility for extension Consideration will also be given to appointing a small team of suitably qualified doctors to provide the service on a rotational basis for periods of 4-6 months each over a period of 3-5 years Salary: £100,000 per annum Starting date May 2011. An earlier starting date can be considered 2. About Tristan da Cunha The territory of Tristan da Cunha is composed of four islands, Gough, Inaccessible, Nightingale and Tristan itself. The latter three are grouped together while Gough lies some 230 nautical miles (426km) to the south. The main island, Tristan da Cunha, is the remotest inhabited island in the world. -

Constitution of St Helena Ascension and Tristan Da Cunha

ST. HELENA (Chapter No. not allocated yet) THE CONSTITUTION OF ST. HELENA, ASCENSION AND TRISTAN DA CUNHA Non-authoritative Consolidated Text This is not an authoritative ‘revised edition’ for the purposes of the Revised Edition of the Laws Ordinance; it has been prepared under the supervision of the Attorney General for the purpose of enabling ready access to the current law, and specifically for the purpose of being made accessible via the internet. Whilst it is intended that this version accurately reflects the current law, users should refer to the authoritative texts in case of doubt. Enquiries may be addressed to the Attorney General at Essex House, Jamestown [Telephone (+290) 2270; Fax (+290 2454; email [email protected]]1 Visit our LAWS page to understand the St. Helena legal system and the legal status of this version of the Ordinance. This version contains a consolidation of the following laws— Page ST HELENA, ASCENSION AND TRISTAN DA CUNHA CONSTITUTION ORDER 2 Statutory Instrument 2009 No. 1751 (UK) ... in force 1 September 2009 CONSTITUTION OF ST. HELENA, ASCENSION AND TRISTAN DA CUNHA 6 Statutory Instrument 2009 No. 1751 (UK); Schedule ... in force 1 September 2009 COUNCIL COMMITTEES (RULES OF PROCEDURE) ORDER 114 Legal Notice 2 of 2010 COUNCIL COMMITTEES (CONSTITUTION) ORDER 119 Legal Notice 3 of 2010 SEE ALSO: ST HELENA, ASCENSION AND TRISTAN DA CUNHA ROYAL INSTRUCTIONS 123 1 These contact details may change during 2011 or early in 2012. In case of difficulty, email [email protected] or telephone (+290) 2470. LAWS OF 2 CAP. Constitution ST. -

Oil Spill Response in Low Level Planning and Preparedness Areas: a Case Study

Oil spill response in low level planning and preparedness areas: a case study Franck Laruelle - ITOPF Nightingale Islands is a small (3.2 km2) uninhabited island which is part of the Tristan da Cunha (TdC) group in the South Atlantic. Tristan da Cunha is part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha. It is formed of four main islands, Tristan da Cunha, Inaccessible, Gough and Nightingale. Adjacent to Nightingale Island are two small islets, Middle Island and Stoltenhoff Island. Tristan da Cunha Island is approximately 18nm North of Nightingale and has a settlement, Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, of 262 inhabitants. Inaccessible Island is approximately 10 nautical miles to the North West of Nightingale and is part of a UNESCO World Heritage site. Gough is located 206 nautical miles in the South-Southeast of Nightingale Island. Nightingale is seabird sanctuary hosting many endemic and endangered species in large numbers (more than 2 million birds) and it is rodent-free. Nightingale is, in particular, home of a significant proportion (13-18%) of the world breeding population of Northern Rockhopper penguin. The other colonies are located on other islands of the Tristan da Cunha group (on Gough in particular with 30 to 43% of the world breeding population) and on Amsterdam and Saint Paul Islands in the South Indian Ocean. Overall, 68 to 77% of the estimated breeding population is found on islands of the Tristan da Cunha group. INCIDENT On Wednesday 16th March 2011, bulk carrier MS OLIVA (GT 40,170) laden with a cargo of 65,000 tons of soya beans on transit from Brazil to Singapore grounded early in the morning on Nightingale Island. -

BEST Ecosystem Profile of the South Atlantic Region

EUROPEAN OVERSEAS REGIONAL ECOSYSTEM PROFILE South Atlantic Ascension Island Saint Helena Tristan da Cunha Falkland Islands (Malvinas) This document has been developed as part of the project ‘Measures towards Sustaining the BEST Preparatory Action to promote the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and ecosystem services in EU Outermost EU Outermost Regions and Overseas Countries and Territories’. The document does not represent an official, formal position of the European Commission. JUNE2016 2016 Service contract 07.0307.2013/666363/SER/B2 Prepared by: South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute (SAERI) And with the technical support of: IUCN CEPF Drafted by the BEST team of the South Atlantic hub: Maria Taylor Under the coordination of: Dr Paul Brickle and Tara Pelembe Assisted by individual experts and contributors from the following institutions: Ascension Island: Ascension Island Government Conservation Department Dr Sam Weber Dr Judith Brown Dr Andy Richardson Dr Nicola Weber Emma Nolan Kate Downes University of Exeter Dr Annette Broderick Dr Brendon Godley St Helena: St Helena Government Isabel Peters Samantha Cherrett Annalea Beard Elizabeth Clingham Derek Henry Mike Jervois Lourens Malan Dr Jill Keys Ross Towers Paul Cherrett St Helena National Trust Jeremy Harris Rebecca Cairn-Wicks David Pryce Dennis Leo Acting Governor Sean Burns Independent Dr Andre Aptroot Dr Phil Lambdon Ben Sansom Tristan da Cunha: Tristan da Cunha Government Trevor Glass James Glass Katrine Herian Falkland Islands: Falkland Island Government -

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TRENTO Labour, Environment and Empire in the South Atlantic

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TRENTO Dottorato in Studi Umanistici - XXVIII Ciclo Indirizzo di Studi Storici Labour, Environment and Empire in the South Atlantic (1780-1860) Relatrice: Prof.ssa Sara Lorenzini Co-Relatrice: Prof.ssa Elena Dai Prà Candidato: Mattia Pessina A.A. 2014-2015 But then, I suppose we all are, in our own way, aren’t we? Bootmakers to Kings THE GOOD SHEPERD (USA, 2009 Table of contents List of abbreviations ...................................................................................................................... 5 List of tables .................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 6 The aim and structure of this thesis ............................................................................................... 7 Sources ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 13 Chapter I - The historical and geographical context ...................................................................... 14 1.1 Historical Geography of the South Atlantic .......................................................................... 16 1.2 The South Atlantic Ocean .................................................................................................... -

Solomon's Theft: Mr Grocock's Charges Said

www.sams.sh THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. Vol. 8,SENTINEL Issue 45 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 13 February 2020 Solomon’s theft: Mr Grocock’s charges said to have been dropped Pilling Year 3 students talk about SHFC closure Blisters for Trees posing “significant Sisters risk to life/property” being removed The RMS: Memories from the final voyage Freight subsidised for Voyage 26 SHG wants telecoms providers who can ensure “cable delivers intended benefits” 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 13 February 2020 | THE SENTINEL THE SENTINEL | Thursday 13 February 2020 www.sams.sh 3 OPINION YOUR LETTERS ST HELENA NEWS Dear Editor, memories when you reminisce about to ceiling images of the Peaks, As the number of visitors are known impression once, and this is a missed it years later. Jamestown, High Knoll and so on. beforehand, the amounts needed can opportunity to create a truly unique SENTINEL An open letter to Airlink and St Now, not being one to just pass They could even be painted for a be managed. What a delight it would St Helenian welcome. Helena Airport comment and leave it at that. Here more personal touch. Maybe even be that once you clear customs a treat Please Airlink and St Helena Airport are some thoughts about how some of the larger endemics in pots awaits you. It would be a memorable do consider the thoughts of this COMMENT Flying into St Helena is an arriving on St Helena could be more could be arranged around the space arrival. -

The World Factbook

The World Factbook Africa :: Saint Helena, Ascension, and Tristan da Cunha (overseas territory of the UK) Introduction :: Saint Helena, Ascension, and Tristan da Cunha Background: Saint Helena is a British Overseas Territory consisting of Saint Helena and Ascension Islands, and the island group of Tristan da Cunha. Saint Helena: Uninhabited when first discovered by the Portuguese in 1502, Saint Helena was garrisoned by the British during the 17th century. It acquired fame as the place of Napoleon BONAPARTE's exile from 1815 until his death in 1821, but its importance as a port of call declined after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. During the Anglo-Boer War in South Africa, several thousand Boer prisoners were confined on the island between 1900 and 1903. Ascension Island: This barren and uninhabited island was discovered and named by the Portuguese in 1503. The British garrisoned the island in 1815 to prevent a rescue of Napoleon from Saint Helena. It served as a provisioning station for the Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron on anti-slavery patrol. The island remained under Admiralty control until 1922, when it became a dependency of Saint Helena. During World War II, the UK permitted the US to construct an airfield on Ascension in support of transatlantic flights to Africa and anti-submarine operations in the South Atlantic. In the 1960s the island became an important space tracking station for the US. In 1982, Ascension was an essential staging area for British forces during the Falklands War. It remains a critical refueling point in the air-bridge from the UK to the South Atlantic. -

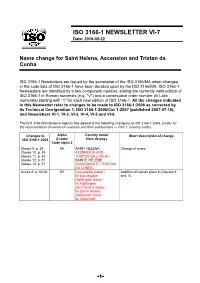

ISO 3166-1 NEWSLETTER VI-7 Date: 2010-02-22

ISO 3166-1 NEWSLETTER VI-7 Date: 2010-02-22 Name change for Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha ISO 3166-1 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-1 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-1 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-1 in Roman numerals (e.g. "V") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-1. All the changes indicated in this Newsletter refer to changes to be made to ISO 3166-1:2006 as corrected by its Technical Corrigendum 1, ISO 3166-1:2006/Cor 1:2007 (published 2007-07-15), and Newsletters VI-1, VI-2, VI-3, VI-4, VI-5 and VI-6. The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency has agreed to the following change(s) to ISO 3166-1:2006, Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 1: Country codes. Changes to Alpha Country name/ Short description of change ISO 3166-1:2006 2-code/ Nom de pays Code alpha 2 Clause 9, p. 24 SH SAINT HELENA, Change of name Clause 10, p. 39 ASCENSION AND Clause 11, p. 46 TRISTAN DA CUNHA / Clause 12, p. 51 SAINTE-HÉLÈNE, Clause 13, p. 57 ASCENSION ET TRISTAN DA CUNHA Annex A, p. 60-61 SH Inaccessible Island / Addition of islands given in Clauses 9 Île Inaccessible and 10 Nightingale Island / Île Nightingale Saint Helena Island / Île Sainte Hélène Stoltenhoff Island / Île Stoltenhoff - 1 - ISO 3166-1 Newsletter VI-7 (2010-02-22) Page 24, Clause 9 Replace the present entry for -

Tristan Da Cunha Biodiversity Action Plan

Tristan Biodiversity Action Plan (2006 – 2010) Tristan Island Government in partnership with The Royal Society for the The University of Cape Town Protection of Birds January 2006 Tristan da Cunha Biodiversity Action Plan Enquiries relating to this plan: Simon Glass Conservation Officer Tristan [email protected] James Glass Head of Tristan Natural Resources Department Tristan [email protected] Sarah Sanders Country Programmes Manager UK Overseas Territories RSPB [email protected] Cover photograph: Atlantic Yellow-nosed albatross on Nightingale Island with Tristan in the background All photos by: Paul Tyler, Alison Rothwell, Erica Sommer and James Glass Foreword by Lewis Glass Acting Administrator, Tristan da Cunha From the moment Tristão d’Acunha first sighted the islands in 1506, Tristan da Cunha has been recognised as a unique place, with an assemblage of wildlife found nowhere else on the globe. Our very way of life on Tristan has always been dependant on the sustainable harvest of the natural resources of the island, and careful management has protected this resource for future generations. For the first time the Tristan islanders are now fully involved in the conservation of our unique natural heritage, not only for the economy of the islands, but also for the enlightenment and enjoyment of current and future generations. This plan will guide and encourage our efforts to protect our unique islands. Lewis Glass Acting Administrator Tristan da Cunha October 2005 2 By Mike Hentley Administrator, Tristan da Cunha Residents on Tristan, the world’s most isolated island community, well understand the need to live in harmony with nature.