September/October 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

06 10-19-10 TV Guide.Indd 1 10/19/10 7:30:34 AM

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, October 19, 2010 Monday Evening October 25, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , OCT . 22 THROUGH THURSDAY , OCT . 28 KBSH/CBS How I Met Rules Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC Chuck The Event Chase Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX House Lie to Me Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention AMC Halloween Halloween II Halloween ANIM Pit Bulls-Parole Pit Bulls River Monsters Pit Bulls-Parole Pit Bulls CNN Parker Spitzer Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Swamp Loggers American Chopper American Chopper Swamp Loggers American Chopper DISN Halloweentown II: Revenge Deck Wizards Wizards Sonny Sonny Hannah Hannah E! What's Eating You Kardashian Fashion The Soup Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN Countdown NFL Football SportsCenter ESPN2 MLB Special 2010 Poker 2010 Poker E:60 NASCAR Now FAM TMNT Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Made of Honor Two Men Two Men Halloween: Resurrection HGTV Property First House Designed House Hunters My First My First House Designed HIST Pawn Pawn American American Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn LIFE Reba Reba Gracie's Choice How I Met How I Met Gracie's Choice Listings: MTV Jersey Shore Jersey Shore World Buried World Buried My Super 2 NICK My Wife My Wife Chris Chris George Lopez The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny SCI Scare Scare Scare Scare Scare Scare Gundam Gundam Darkness Darkness For your SPIKE UFC Fight Night Halloween BlueMount Most Amazing Videos TBS Fam. -

Discovery Communications, Inc. Fundamental Company Report Including Financial, SWOT, Competitors and Industry Analysis

+44 20 8123 2220 [email protected] Discovery Communications, Inc. Fundamental Company Report Including Financial, SWOT, Competitors and Industry Analysis https://marketpublishers.com/r/D53153D2062BEN.html Date: September 2021 Pages: 50 Price: US$ 499.00 (Single User License) ID: D53153D2062BEN Abstracts Discovery Communications, Inc. Fundamental Company Report provides a complete overview of the company’s affairs. All available data is presented in a comprehensive and easily accessed format. The report includes financial and SWOT information, industry analysis, opinions, estimates, plus annual and quarterly forecasts made by stock market experts. The report also enables direct comparison to be made between Discovery Communications, Inc. and its competitors. This provides our Clients with a clear understanding of Discovery Communications, Inc. position in the Media Industry. The report contains detailed information about Discovery Communications, Inc. that gives an unrivalled in-depth knowledge about internal business-environment of the company: data about the owners, senior executives, locations, subsidiaries, markets, products, and company history. Another part of the report is a SWOT-analysis carried out for Discovery Communications, Inc.. It involves specifying the objective of the company's business and identifies the different factors that are favorable and unfavorable to achieving that objective. SWOT-analysis helps to understand company’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and possible threats against it. The Discovery Communications, Inc. financial analysis covers the income statement and ratio trend-charts with balance sheets and cash flows presented on an annual and quarterly basis. The report outlines the main financial ratios pertaining to profitability, margin analysis, asset turnover, credit ratios, and Discovery Communications, Inc. Fundamental Company Report Including Financial, SWOT, Competitors and Industry.. -

Composer (Films)

SARAH SCHACHNER AWARDS & NOMINATIONS HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA Call of Duty: Modern Warfare AWARD (2019) Original Score – Video Game INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC ASSASSIN’S CREED: UNITY CRITICS ASSOCIATION AWARD NOMINATION Best Original Score for a Video Game or Interactive Media *Shared VIDEOGAMES CALL OF DUTY: MODERN Activision WARFARE ANTHEM Electronic Arts ASSASSIN’S CREED: ORIGINS Ubisoft CALL OF DUTY: INFINITE Activision WARFARE ASSASSIN’S CREED: UNITY, VOL 2 Ubisoft *Co-composer ARMY OF TWO: DEVIL’S CARTEL Electronic Arts *Additional music, Additional violin, Additional cello CALL OF DUTY MODERN Activision WARFARE 3 *Additional Music for Brian Tyler NEED FOR SPEED: THE RUN Electronic Arts *Additional Music for Brian Tyler FAR CRY Ubisoft *Additional Music for Brian Tyler TRUE CRIME: HONG KONG Square Enix *Additional Music for Brian Tyler The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 SARAH SCHACHNER FILM THE LAZARUS EFFECT Jason Blum, Luke Dawson, Matt Kaplan, Cody Lionsgate Zwieg, prods. David Gelb, dir. EXPENDABLES 2 Avi Lerner, Danny Lerner, Kevin King Templeton, Millennium Films John Thompson, Les Weldon, prods. *Musical Score Arrangements Simon West, dir. IRON MAN 3 Kevin Feige, prod. Paramount Pictures Shane Black, dir. *Musical Score Arrangements NOW YOU SEE ME Bobby Cohen, Alex Kurtzman, Roberto Summit Entertainment Orci, prods. *Musical Score Arrangements Louis Leterrier, dir. UNHUNG HERO Lynn Schmitz, prod. Brian Spitz, dir. REMAINS Andrew Gernhard, Zach O’Brien, prods. Synthetic Cinema International Colin Theys, dir. COOL IT Terry Botwick, Sarah Gibson, 1019 Entertainment Ondi Timoner, prods. Ondi Timoner, dir. TELEVISION CHEF’S TABLE: JORDI ROCA I David Gelb, exec. prod. FONTANÉ Netflix THE TROOP Max Burnett, Jay Kogen, Greg Coolidge, Nickelodeon Tommy Lynch, exec. -

2009 Annual Report 25 Years of Satisfying Curiosity

2009 ANNUAL REPORT 25 YEARS OF SATISFYING CURIOSITY CANADA UNITED STATES LATIN AMERICA The world’s #1 nonfi ction media company MORE THAN 100 WORLDWIDE NETWORKS IN OVER 170 COUNTRIES AND 38 LANGUAGES UNITED KINGDOM EUROPE ASIA MIDDLE EASTST AFRICA AUSTRALIA DISCOVERY COMMUNICATIONS 2009 ANNUAL REPORT DEAR SHAREHOLDERS, 6% affi liate revenue growth. Internationally, Discovery’s networks leveraged the continued secular growth trends of As Discovery Communications celebrates our 25th pay-TV around the globe to expand its subscriber base and anniversary in 2010, we are proud to report that the state of deliver 9% affi liate revenue growth, excluding the impact of the company is strong and we are well positioned to deliver foreign currency fl uctuations. value for our shareholders by building upon our mission of Given the opportunities to further expand Discovery’s satisfying curiosity and making a difference as the world’s leadership overseas, near the end of 2009, we announced number one nonfi ction media company. that 18-year veteran Mark Hollinger would assume total This past year, in the face of the most challenging economic oversight of our international businesses. Elevating this environment in a generation, Discovery was able to function and placing it in the hands of one of our most increase top-line revenue and diligently cut costs, leading to experienced and capable leaders demonstrates our double-digit adjusted OIBDA and free cash fl ow growth. commitment and steadfast approach to expanding both our international revenues and margins. Overall, for the year, total revenue increased 2% to $3,516 million, primarily driven by 4% growth at U.S. -

Rains Came but Too Late for Corn Game?

i)PXDBO*HFUBDPQZPG r1PTUUSJQT1PTUJOTFSJFTPQFOFS BOPMETUPSZPSQIPUPUIBU r8IJUFWJMMF0QUJNJTUUBLFTTFDPOE US SBOJOTe News Reporter u TUSBJHIUXJOJO%JTUSJDU%JYJF:PVUI i"SFUIPTFIJHIJOUFOTJUZ .BKPS5PVSOBNFOUr$PMVNCVT%J DPMPSFEOFPOMJHIUTMFHBM YJF(JSMTUFBNTIFBEJOUPUPEBZTUIJSE Sports Ask POWFIJDMFT u SPVOEPGTUBUFUPVSOBNFOU 4FFBOTXFSTPOQBHF" 4FFQBHF# ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Tursday forReporter the County of Columbus and her people. Monday, July 11, 2011 Pleas made in 2007 spill Volume 121, Number 3 Whiteville, North Carolina of hog waste 50 Cents nFederal court sentenc- ing is probable within 90 days. Inside Today By BOB HIGH 4-A Staff Writer r3BJO4BUVSEBZëPPET William Barry Freedman VQUPXOIFSF of Freedman Farms Inc., en- r5XPHFUQSJTPOBT tered a misdemeanor plea last QSPCBUJPOSFWPLFE Wednesday to violating the U.S. Clean Water Act by allowing a spill of hog waste in 2007, DIDYOB? and the corporation entered a felony plea to the same offense Did you observe ... in a New Bern federal court. Sentencing is to be set by Austin Kenyon of Staff photo by Mark Gilchrist Federal Judge Louise Flana- A deluge of rain fooded much of Whiteville early Saturday evening, including J.K. Powell Boulevard just south Whiteville Opti- gan, and is probable within 90 of Washington Street. Northbound lanes were impassable for about an hour, and only brave, careless or well- mists hitting a walk days. Freedman faces a term equipped motorists forded the southbound lanes. Three fooded cars blocked traffc until tow trucks arrived. See of up to a year in prison and/ story and more photos on page 4-A. of a two-run home or probation, and government run in Wednesday prosecutors asked for the farm corporation to pay a fine of $1.5 night’s AAA District million. -

DANIKA WIKKE Supervising Sound Editor

DANIKA WIKKE Supervising Sound Editor DIARY OF A FEMALE PRESIDENT Ilana Peña Disney + SSE BROOKLYN NINE-NINE (SEASON SSE Michael Schur Fox Network 7) SCREAM: THE TV SERIES SSE Jay Beattie MTV (SEASON 3) AMERICAN PRINCESS Jamie Denbo Lifetime Television SADR BETTER THINGS (SEASON 2-3) Pamela Adlon FX Network SSE CRAZY EX-GIRLFRIEND Rachel Bloom The CW SSE GLAMOROUS (PILOT) Thom J. Pretak CBS SSE FRESH OFF THE BOAT (1 ADR Nahnatchka Khan ABC EPISODE, SEASON 5) SPEECHLESS (2 EPISODES, SADR Scott Silveri ABC SEASON 3) ADR, STARTUP Ben Ketai Crackle DE MODERN FAMILY (1 EPISODE, ADR Steven Levitan ABC SEASON 10) STREET OUTLAWS (4 EPISODES, SE, DE David Charles Sullivan Discovery Channel SEASON 10) DEADLIEST CATCH (2 DE Brian Lovett Discovery Channel EPISODES, SEASON 13) DAVID TUTERA'S CELEBRATIONS David Charles Sullivan We TV Network SE RAISING WHITLEY Christopher C. Schiavo Pilgrim Films & Television SE, DE SOMEBODY'S GOTTA DO IT (7 SE, DE Mike Rowe TBN EPISODES, SEASON 1) THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER Thomas Loureiro Spike TV DE MISFIT GARAGE (2 EPISODES, DE Paul Baker Pilgrim Studios SEASON 1 ) WICKED TUNA (NORTH VS. SE Numa Fernandez National Geographic Channel SOUTH) GHOST HUNTERS Richard Monahan The Sci-Fi Channel SE, DE BRING IT! Dax Rhorer Lifetime Television SE SHARK OF DARKNESS: WRATH SE Doug Glover Discovery Channel OF SUBMARINE (TV MOVIE) Formosa Broadcast www.FormosaGroup.com/Broadcast 323.853.0008 [email protected] Page 1 #BIKERLIVE Paul Baker Pilgrim Studios SE WICKED TUNA Zachary Boggs Pilgrim Studios SE DOWN EAST DICKERING Paul Baker Pilgrim Studios SE OWN: The Oprah Winfrey SE LINDSAY (TV MINI-SERIES) Amy Rice Network FAST N' LOUD: DEMOLITION SE THEATER (1 EPISODE, SEASON Doug Bruckner Discovery Channel 4) FAST N' LOUD Aaron Krummel Discovery Channel SE ORANGE COUNTY CHOPPERS Anthony McLemore SE KILLER CONTACT Syfy SE SWAMP PAWN CMT SE SPARTAN RACE (TV MOVIE) Joe Guidry Pilgrim Studios DE DAVID TUTERA: UNVEILED Steven C. -

Latest Developments in Steep Slope Logging

issue 40 | july 2015 Latest OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF TIGERCAT INDUSTRIES INC. developments in steep slope logging. Product News 2 Living Laboratory 19 My Tigercat Circus 4 Event Round-up 22 How Steep is Steep in NZ? 8 Construction Update 25 How to Move Timber in France 10 Dealer News 26 First 1085B Forwarder 16 Employee News 28 151327 btb.indd 1 2015-07-22 11:43 AM product news TIGERCAT POWERED 234B LOADER Tigercat has recently released the 234B and the operator experience. The new heavy duty T234B series knuckleboom loaders with notable suspension seat is physically wider and standard improvements, including the addition of a Tigercat equipped with heating and cooling. The seat also has FPT Tier 4f power plant and a totally redesigned improved adjustability and many of the frequently cabin. used rocker switches have been repositioned – integrated into The new 234B and T234B the armrest mounted joystick loaders are now equipped with pod for enhanced ergonomics. the Tigercat FPT N45 engine, The climate control system delivering 125 kW (168 hp). The is further augmented by the four-cylinder engine was chosen addition of window blinds for because it is very well matched to the front windshield and skylight. the duty cycle of the 234 series Acoustical engineering along with loaders, enhancing fuel effi ciency, the quiet N45 engine contribute reducing DEF consumption and to extremely low in-cab sound improving the performance of levels, while the new sound the aftertreatment components. system with Bluetooth® audio Lifting force and boom speed are allows for hands-free calling. unaffected by the engine change and operators are reporting The 234B platform is versatile the same high performance for a variety of applications. -

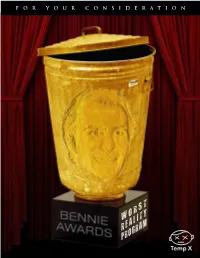

Worst Reality Program PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK the Vexcon Pest Removal Team Helps to Rid Clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E Their Extreme Pest Cases

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION WORST REALITY PROGRAM PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK The Vexcon pest removal team helps to rid clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E their extreme pest cases. Performance series featuring Criss Angel, a master Criss Angel: Mindfreak illusionist known for his spontaneous street A&E performances and public shows. Reality series which focuses on bounty hunter Duane Dog the Bounty Hunter "Dog" Chapman, his professional life as well as the A&E home life he shares with his wife and their 12 children. A docusoap following the family life of Gene Simmons, Gene Simmons Family Jewels which include his longtime girlfriend, Shannon Tweed, a A&E former Playmate of the Year, and their two children. Reality show following rock star Dee Snider along with Growing Up Twisted A&E his wife and three children. Reality show that follows individuals whose lives have Hoarders A&E been affected by their need to hoard things. Reality series in which the friends and relatives of an individual dealing with serious problems or addictions Intervention come together to set up an intervention for the person in A&E the hopes of getting his or her life back on track. Reality show that follows actress Kirstie Alley as she Kirstie Alley's Big Life struggles with weight loss and raises her two daughters A&E as a single mom. Documentary relaity series that follows a Manhattan- Manhunters: Fugitive Task Force based federal task that tracks down fugitives in the Tri- A&E state area. Individuals with severe anxiety, compulsions, panic Obsessed attacks and phobias are given the chance to work with a A&E therapist in order to help work through their disorder. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/18/11

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/18/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at St. Louis Rams. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Snowboarding USSA Grand Prix. Å Action Sports From Breckenridge, Colo. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program Friends Friends 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. Paid Program 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Prince Mike Webb Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Washington Redskins at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Hates Chris 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Cuisine Kitchen Kitchen Sweet Life 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid McMahon Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) Vidas Paralelas Vecinos 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Discovery Channel September 2013 Program Schedule

Discovery Channel September 2013 Program Schedule For SEA Only 08/31/2013 Bear's Top 25 Moments 06:00 Dirty Jobs With Peter Schmeichel 10:00 Kids Vs. Film Poland Reel Animals 07:00 How It's Made 18 10:30 Gastronuts Wax Figures/awnings/sandwich Crackers/pewter Tankards Can We Eat The Same Food As Animals? 07:30 Factory Made 11:00 Mythbusters 9 Episode 3 Fright Night 08:00 Mythbusters 9 12:00 Swamp Loggers 2 Episode 204 All In 09:00 Beyond Survival With Les Stroud 13:00 Top Hooker Sri Lanka Episode 1 10:00 Think Big 14:00 Amish Mafia Episode 6 Holy War 10:30 Gastronuts 15:00 North America What Would Happen If We Didn't Fart? Outlaws And Skeletons 11:00 How It's Made 18 16:00 Man Vs. Wild 5 Wax Figures/awnings/sandwich Crackers/pewter Tankards Bear's Top 25 Moments 11:30 Factory Made 17:00 Top Hooker Episode 3 Episode 1 12:00 The Devils Ride 2 18:00 Mythbusters 9 Episode 6 Fright Night 13:00 Man Vs. Wild 5 19:00 Brew Masters Bear's Top 25 Moments Bitches Brew 14:00 Mythbusters 9 20:00 Who Framed Jesus? Episode 204 22:00 Man, Woman, Wild 2 15:00 What Happened Next? Louisiana Firestorm Episode 3 23:00 North America 15:30 The Magic Of Science Outlaws And Skeletons Vortex Cannon 09/02/2013 16:00 Brew Masters 00:00 Who Framed Jesus? Bitches Brew 02:00 Top Hooker 17:00 Swamp Loggers 2 Episode 1 All In 03:00 Brew Masters 18:00 The Devils Ride 2 Bitches Brew Episode 6 04:00 Man Vs. -

TAL Direct: Sub-Index S912c Index for ASIC

TAL.500.002.0503 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Appendix B: Reference to xv: A list of television programs during which TAL’s InsuranceLine Funeral Plan advertisements were aired. 1 90802531/v1 TAL.500.002.0504 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Section 1_xv List of TV programs FIFA Futbol Mundial 21 Jump Street 7Mate Movie: Charge Of The #NOWPLAYINGV 24 Hour Party Paramedics Light Brigade (M-v) $#*! My Dad Says 24 HOURS AFTER: ASTEROID 7Mate Movie: Duel At Diablo (PG-v a) 10 BIGGEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW IMPACT 7Mate Movie: Red Dawn (M-v l) 10 CELEBRITY REHABS EXPOSED 24 hours of le mans 7Mate Movie: The Mechanic (M- 10 HOTTEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW 24 Hours To Kill v a l) 10 Things You Need to Know 25 Most Memorable Swimsuit Mom 7Mate Movie: Touching The Void 10 Ways To Improve The Value O 25 Most Sensational Holly Melt -CC- (M-l) 10 Years Younger 28 Days in Rehab 7Mate Movie: Two For The 10 Years Younger In 10 Days Money -CC- (M-l s) 30 Minute Menu 10 Years Younger UK 7Mate Movie: Von Richthofen 30 Most Outrageous Feuds 10.5 Apocalypse And Brown (PG-v l) 3000 Miles To Graceland 100 Greatest Discoveries 7th Heaven 30M Series/Special 1000 WAYS TO DIE 7Two Afternoon Movie: 3rd Rock from the Sun 1066 WHEN THREE TRIBES WENT 7Two Afternoon Movie: Living F 3S at 3 TO 7Two Afternoon Movie: 4 FOR TEXAS 1066: The Year that Changed th Submarin 112 Emergency 4 INGREDIENTS 7TWO Classic Movie 12 Disney Tv Movies 40 Smokin On Set Hookups 7Two Late Arvo Movie: Columbo: 1421 THE YEAR CHINA 48 Hour Film Project Swan Song (PG) DISCOVERED 48 -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: Meredith Strober, 310 975 1639 September 13, 2010 Meredith [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: Meredith Strober, 310 975 1639 September 13, 2010 [email protected] Discovery Channel’s Hit Series are Back This October with World Premiere Episodes (Silver Spring, Md.) – The fall TV season is here and Discovery Channel's schedule is bursting with fan favorites. This October, viewers can go along with Mike on new dirty jobs, investigate intriguing paranormal action, use science to test myths and legends, chase dangerous storms and invade murky, dangerous swamps. All Times ET/PT. MYTHBUSTERS - Returning Wednesdays at 9 PM Beginning October 6th Fresh off its second Emmy® nomination for Outstanding Reality Program, MYTHBUSTERS returns Wednesday, October 6th with explosive world premiere episodes airing throughout the remainder of 2010. Called "the best science show on television," hosts Adam Savage, Jamie Hyneman, Kari Byron, Tory Belleci and Grant Imahara aim to uncover the truth behind popular myths and legends by utilizing their own signature style of experimentation that mixes scientific method with gleeful curiosity and plain old-fashioned ingenuity. In the October 6th premiere episode, Hair of the Dog, find out if man can truly outsmart his best friend as the MYTHBUSTERS test two shaggy-dog tales with the help of crime-fighting canines. Throughout the new fall episodes, the team will tackle myths, both well-known and obscure, including: Is driving tired far more dangerous than driving slightly inebriated? Does being frightened really cause cold feet? Do humans use only 10 percent of their brain? Does changing your tire pressure really give you greater gas mileage? Screeners available upon request. Episodic photos from the new season available at http://press.discovery.com/us/dsc/programs/mythbusters/ SWAMP LOGGERS - Returning Fridays at 9 PM Beginning October 8th Fourth generation logger Bobby Goodson is a rare breed of SWAMP LOGGERS working the murky, dangerous swamps of North Carolina in search of high value timber for everything from paper products to construction grade lumber.