Tweed Webb: ‘He's Seen `Em All’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negro Leagues Baseball Date for Release of the Negro Museum Is a Privately Funded Non- Leagues Baseball Stamp from June Profit Institution

Negro Leagues Stamp to be Issued July 15 The USPS has changed the The Negro Leagues Baseball date for release of the Negro Museum is a privately funded non- Leagues Baseball stamp from June profit institution. On their website, 4 to July 15. The stamp ceremoney <www.nlbm.com>, we are informed will be held at the Negro Leagues that “African-Americans began to Baseball Museum in Kansas City, play baseball in the late 1800s on Mo. military teams, college teams, and The Negro Leagues se-tenant company teams. They eventually stamps pay tribute to the all-black professional baseball leagues that found their way to professional teams with white players. Moses Fleet- operated from 1920 to about 1960. Drawing some of the most remark- wood Walker and Bud Fowler were among the first to participate. How- able athletes ever to play the sport, the Negro leagues galvanized ever, racism and ‘Jim Crow’ laws would force them from these teams by African-American communities across the country, challenged racist 1900. Thus, black players formed their own units, ‘barnstorming’ around notions of athletic superiority, and ultimately sparked the integration the country to play anyone who would challenge them. of American sports. “In 1920, an organized league structure was formed under the One of the stamps pictures a generic scene of a player sliding guidance of Andrew ‘Rube’ Foster….Foster and a few other Midwest- safely into home plate as the catcher awaits the ball. ern team owners joined to form the Negro National League. Soon, The other is a portrait of Andrew “Rube” Foster, a player, man- rival leagues formed in Eastern and Southern states….The Leagues ager, and pioneer executive in the Negro Leagues who organized the maintained a high level of professional skill and became centerpieces Negro National League—the first long-lasting professional league for economic development in many black communities. -

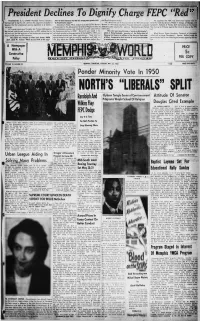

President Declines to Dignify Charge FEPC “Red

■ 1 —ft, President Declines To Dignify Charge FEPC “Red WASHINGTON, D. C.-(NNPA)-President Truman Saturday ment of some Senators that the fair employment practice bill and Engel,s began to write." | The argument that FEPC was Communist Inspired wai ve ) had declined to dignify with comment the argument of Southern is of Communist origin'** Mr. White was one of those present al the While House con hemently made by Senator* Walter F. George, of Georgia, and ference in 194) which resulted in President Roosevelt issuing an I Senator* that fair employment practice legislation is of Commu- According to Walter White, executive secretary of the Nation Spessard I. Holland, of Florida, both Democrats, on the Senate al Association for the Advancement of Colored People the fdea of I ni*t origin. executive aider creating the wartime fair Employment Practice floor during the filibuster ogaintl the motion to take up the FEPC At hi* press conference Thursday, Mr. Truman told reporters fair employment practices was conceived "nineteen years before Committee. ' bill. I that he had mode himself perfectly clear on FEPC, adding that he the Communists did so in 1928." He said it was voiced in the the order was issued to slop a "march on-Woshington", I did not know that the argument of the Southerners concerning the call which resulted in the organization of lhe NAACP in 1909, and which A. Philip Randolph, president of lhe Brotherhood of Whert Senotor Hubert Humphrey, Democrat, of Minnesota I origin of FEPC deserved any comment. that colored churches and other organizations "have cried out Sloeping Car Porters, an affiliate of lhe American Federation called such a charge ’ blasphemy". -

Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter De Rosa Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 7 Jun-2004 Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter de Rosa Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation de Rosa, Peter (2004). Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918. Bridgewater Review, 23(1), 11-14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol23/iss1/7 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Boston Baseball Dynasties 1872–1918 by Peter de Rosa It is one of New England’s most sacred traditions: the ers. Wright moved the Red Stockings to Boston and obligatory autumn collapse of the Boston Red Sox and built the South End Grounds, located at what is now the subsequent calming of Calvinist impulses trembling the Ruggles T stop. This established the present day at the brief prospect of baseball joy. The Red Sox lose, Braves as baseball’s oldest continuing franchise. Besides and all is right in the universe. It was not always like Wright, the team included brother George at shortstop, this. Boston dominated the baseball world in its early pitcher Al Spalding, later of sporting goods fame, and days, winning championships in five leagues and build- Jim O’Rourke at third. ing three different dynasties. Besides having talent, the Red Stockings employed innovative fielding and batting tactics to dominate the new league, winning four pennants with a 205-50 DYNASTY I: THE 1870s record in 1872-1875. Boston wrecked the league’s com- Early baseball evolved from rounders and similar English petitive balance, and Wright did not help matters by games brought to the New World by English colonists. -

Numbered Panel 1

PRIDE 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E The African-American Baseball Experience Cuban Giants season ticket, 1887 A f r i c a n -American History Baseball History Courtesy of Larry Hogan Collection National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 1 8 4 5 KNICKERBOCKER RULES The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club establishes modern baseball’s rules. Black Teams Become Professional & 1 8 5 0 s PLANTATION BASEBALL The first African-American professional teams formed in As revealed by former slaves in testimony given to the Works Progress FINDING A WAY IN HARD TIMES 1860 – 1887 the 1880s. Among the earliest was the Cuban Giants, who Administration 80 years later, many slaves play baseball on plantations in the pre-Civil War South. played baseball by day for the wealthy white patrons of the Argyle Hotel on Long Island, New York. By night, they 1 8 5 7 1 8 5 7 Following the Civil War (1861-1865), were waiters in the hotel’s restaurant. Such teams became Integrated Ball in the 1800s DRED SCOTT V. SANDFORD DECISION NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BA S E BA L L PL AY E R S FO U N D E D lmost as soon as the game’s rules were codified, Americans attractions for a number of resort hotels, especially in The Supreme Court allows slave owners to reclaim slaves who An association of amateur clubs, primarily from the New York City area, organizes. R e c o n s t ruction was meant to establish Florida and Arkansas. This team, formed in 1885 by escaped to free states, stating slaves were property and not citizens. -

Black Diamond 1

Black Diamond 1 Black Diamond “The Greatest Stories Never Told” Series Recommended for Ages 6-11 Grades 1-6 A Reproducible Learning Guide for Educators This guide is designed to help educators prepare for, enjoy, and discuss Black Diamond It contains background, discussion questions and activities appropriate for ages 6-11. Programs Are Made Possible, In Part, By Generous Gifts From: D.C. Commission on the Arts & Humanities DC Public Schools The Nora Roberts Foundation Philip L. Graham Fund PNC Foundation Smithsonian Women's Committee Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program Sommer Endowment Discovery Theater ● P.O. Box 23293, Washington, DC ● www.discoverytheater.org Like us on Facebook ● Instagram: SmithsonianDiscoveryTheater ● Twitter: Smithsonian Kids Black Diamond 2 MEET SATCHEL PAIGE! Leroy “Satchel” Paige was born in Mobile, Alabama in 1906, the sixth of twelve children. His father was a gardener and his mother was a domestic worker. Some say Paige got his nickname while working as a baggage porter. He could carry so many suitcases (or satchels) at one time he looked like a “satchel tree.” At age 12, a truant officer caught Paige skipping school and stealing. As punishment, he was sent to industrial school. “It got me away from the bums.” He said later. “It gave me a chance to polish up my game. It gave me some schooling I’d of never taken if I wasn’t made to go to class.” PITCHING AND BARNSTORMING! Satchel Paige pitched his first Negro League game in 1924 with the semi-pro Mobile Tigers ball club. After a stretch with the Pittsburgh Crawfords, he went to the Kansas City Monarchs, helping them to win half a dozen pennants between the years 1939-1948. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

National League News in Short Metre No Longer a Joke

RAP ran PHILADELPHIA, JANUARY 11, 1913 CHARLES L. HERZOG Third Baseman of the New York National League Club SPORTING LIFE JANUARY n, 1913 Ibe Official Directory of National Agreement Leagues GIVING FOR READY KEFEBENCE ALL LEAGUES. CLUBS, AND MANAGERS, UNDER THE NATIONAL AGREEMENT, WITH CLASSIFICATION i WESTERN LEAGUE. PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE. UNION ASSOCIATION. NATIONAL ASSOCIATION (CLASS A.) (CLASS A A.) (CLASS D.) OF PROFESSIONAL BASE BALL . President ALLAN T. BAUM, Season ended September 8, 1912. CREATED BY THE NATIONAL President NORRIS O©NEILL, 370 Valencia St., San Francisco, Cal. (Salary limit, $1200.) AGREEMENT FOR THE GOVERN LEAGUES. Shields Ave. and 35th St., Chicago, 1913 season April 1-October 26. rj.REAT FALLS CLUB, G. F., Mont. MENT OR PROFESSIONAL BASE Ills. CLUB MEMBERS SAN FRANCIS ^-* Dan Tracy, President. President MICHAEL H. SEXTON, Season ended September 29, 1912. CO, Cal., Frank M. Ish, President; Geo. M. Reed, Manager. BALL. William Reidy, Manager. OAKLAND, ALT LAKE CLUB, S. L. City, Utah. Rock Island, Ills. (Salary limit, $3600.) Members: August Herrmann, of Frank W. Leavitt, President; Carl S D. G. Cooley, President. Secretary J. H. FARRELL, Box 214, "DENVER CLUB, Denver, Colo. Mitze, Manager. LOS ANGELES A. C. Weaver, Manager. Cincinnati; Ban B. Johnson, of Chi Auburn, N. Y. J-© James McGill, President. W. H. Berry, President; F. E. Dlllon, r>UTTE CLUB, Butte, Mont. cago; Thomas J. Lynch, of New York. Jack Hendricks, Manager.. Manager. PORTLAND, Ore., W. W. *-* Edward F. Murphy, President. T. JOSEPH CLUB, St. Joseph, Mo. McCredie, President; W. H. McCredie, Jesse Stovall, Manager. BOARD OF ARBITRATION: S John Holland, President. -

Washington, Dc and the Mlb All-Star Game

TEAM UP FEBRUARY TOUCH BASE 2021 WASHINGTON, DC AND THE MLB ALL-STAR GAME The Major League Baseball All-Star Game is also known as the “Midsummer Classic.” The game features the best players in the National League (NL) playing against the best players in the American League (AL). Fans choose the starting lineups; and a combination of players, coaches, and managers choose the rest of the players on the All-Star rosters. The game is played every year, usually on the second or third Tuesday in July. The very first All-Star Game was on July 6, 1933, at the home of the Chicago White Sox. Only two times since then has the game not been played — in 1945 due to World War II travel restrictions, and 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. Nationals Park and Washington, DC were at the center of the baseball universe in July 2018, serving as host of the 89th Major League Baseball All-Star Game. Remember all those festivities? This may come as a surprise, but that was actually the fifth time the All-Star Game was played in DC. Here is a little bit about each of the All-Star Games played in the Nation’s Capital. JULY 7, 1937 The 1937 Midsummer Classic, which was the fifth Major League Baseball All-Star Game, was played on July 7, at Griffith Stadium. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was in attendance, making this the first All-Star Game to be played in front of a current President. The American League won the game 8-3, improving to 4 wins and 1 loss in the five games. -

Lesson 2 – Pre-Visit the Negro Leagues

Civil Rights History: Before You Could Say "Jackie Robinson" – Level 1 Lesson 2 – Pre-Visit The Negro Leagues Objective : Students will be able to: • Identify important individuals associated with the formation and success of the Negro leagues. • Practice research and note-taking skills. Time Required : One class period Advance Preparation: - Cut out the photos from the Negro leagues Players photo pages (included). - Request a copy of either of the following books from your school library: o Negro Leagues: All-Black Baseball by Laura Driscoll and Tracy Mitchell o Fair Ball! 14 Great Stars from Baseball's Negro leagues by Jonah Winter Materials Needed : - A copy of either of the books listed above - A variety of baseball cards - 1 for each student in the class - Card stock - Glue or glue sticks - Copies of the Negro leagues Baseball Card graphic organizers for each student (included) - Negro leagues Players photo page (included) - Internet access for student research Vocabulary: Barnstorming - To tour an area playing exhibition games Civil Rights - The rights to full legal, social, and economic equality extended to African Americans Discrimination - Making a distinction in favor of, or against, a person based on a category to which that person belongs rather than on individual merit Jim Crow Laws - Any state law discriminating against black persons Negro leagues - Any of the organized groups of African American baseball teams active between 1920 and the late 1950s Segregation - The separation or isolation of a race, class, or ethnic group by the use of separate facilities, restricted areas, or by other discriminatory means 15 Civil Rights History: Before You Could Say "Jackie Robinson" – Level 1 Applicable Common Core State Standards: RI.3.1. -

Achieve Gr. 6-A League of Their

5/17/2021 Achieve3000: Lesson Printed by: Thomas Dietz Printed on: May 17, 2021 A League of Their Own Article RED BANK, New Jersey (Achieve3000, May 5, 2021). From 1920 into the 1950s, summer Sundays in parts of Kansas City revolved around Black baseball games. Families dressed in their best. Crowds by the thousands gravitated to the stadium. Fans watched their Kansas City Monarchs play the Chicago American Giants, the Homestead Grays, or the Newark Eagles. It was more than a joyful day out at the ballgame. It was a celebration. That scene captures the excitement of the "Negro Leagues," as they were known at the time. In that era, segregation policies blocked Black citizens from enjoying many aspects of American life. This included Major League Photo Credit: AP Photo/Matty Baseball. Black baseball teams were a source of fun and community pride. Zimmerman, File In this photo from 1942, Kansas City Chicago-based Andrew "Rube" Foster had the grand vision to launch the Monarchs pitcher Leroy Satchel Negro National League. It started in 1920 with eight teams. In 1933, the Paige warms up before a Negro League game. New Negro National League was founded, followed by the Negro American League. The financial fortunes of the Negro Leagues would ebb and flow over the next three decades. But their popularity and high-level of play stayed strong. Between World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945), baseball's place as America's national pastime was indisputable. The segregated Major Leagues fielded Hall of Fame legends like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Dazzy Vance. -

Numbered Panel 2

2A 2B 2C 2D 2E Broadside featuring the Belmont Colored Giants of Harlem, 1908 Courtesy of National Baseball Hall of Fame Library A f r i c a n -American History Baseball History 1 8 8 7 GENTLEMEN’S AGREEMENT Midway through the season, International League owners agree to sign no new contracts with African-American baseball players, sparking the tradition of barring black players from pro ball. Other leagues follow and the era of integrated baseball soon ends. BARNSTORMING ON THE OPEN ROAD 1887–1919 NATIONAL COLORED BASE BALL LEAGUE With teams from Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Cincinnati, LINCOLN GIANTS Land of Giants Washington, Pittsburgh, Baltimore and Louisville, this league fails within three weeks of its May opener. By 1887, some black players were on organized baseball rosters, Many black barn s t o rmi ng teams took the name “Giants” arguably because 1 8 9 1 mainly in the minor leagues. But during that season, the International of the prominence of the National AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOLDS Financially weakened by long years of competition with the National L e a g u e ’s New York Giants, who were League, the American Association fails. League owners agreed to make no new contracts with African- managed by John McGraw. These American players. In unspoken agreement, other leagues adopted black teams, among them the 1 8 9 6 Mohawk Giants of Schenectady, PLESSY V. FERGUSON DECISION similar policies over the next 15 years. Black players, in response, the Union Giants of Chicago and the In a test of Jim Crow laws, the Supreme Court allows “separate Lincoln Giants of New York City, but equal” schools and public accommodations for African Americans, thereby supporting segregation of schools and started their own professional teams. -

One of Baseball's Greatest Catchers

Excerpt • Temple University Press 1 ◆ ◆ ◆ One of Baseball’s Greatest Catchers f all the positions on a baseball diamond, none is more demanding or harder to play than catcher. The job behind the plate is without question the most difficult to perform, Oand those who excel at it rank among the toughest players in the game. To catch effectively, one has to be a good fielder, have a good throwing arm, be able to call the right pitches, be a good psy- chologist when it comes to dealing with pitchers, know how to engage tactfully with umpires, how to stave off injuries, and have the fortitude to block the plate and to stand in front of speeding or sliding runners and risk serious injury. Catching is not a position for the dumb or the lazy or the faint-hearted. To wear the mask and glove, players have to be smart. They have to be tough, fearless, and strong. They must be alert, agile, and accountable. They are the ones in charge of their teams when on the field, and they have to be able to handle that job skillfully. Excerpt • Temple University Press BIZ MACKEY, A GIANT BEHIND THE PLATE There are many other qualities required of a good catcher that, put together, determine whether or not players can satisfac- torily occupy the position. If they can’t, they will not be behind the plate for long. Rare is the good team that ever took the field without a good catcher. And yet, while baseball has been richly endowed with tal- ented backstops, only a few have ever made it to the top of their profession.