Making College Affordability a Priority: Promising Practices and Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read the Letter from University Presidents (PDF)

September 13, 2012 President Barack Obama The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave Washington, D.C. 20500 Sen. Harry Reid Sen. Mitch McConnell Senate Majority Leader Senate Republican Leader 522 Hart Senate Office Building 317 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 Hon. John Boehner Hon. Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House Democratic Leader H-232, US Capitol H-204, US Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Mr. President, Majority Leader Reid, Republican Leader McConnell, Speaker Boehner, and Democratic Leader Pelosi: As leaders of universities educating the creators of tomorrow’s scientific breakthroughs, we call on you to address a critical threat to America’s preeminence as a global center of innovation and prosperity: our inability under current United States immigration policy to retain and benefit from many of the top minds educated at our universities. From the industrial revolution to today’s information age, the United States has led the world in creating the inventions and ideas that drive economic prosperity. America’s universities are responsible for 36 percent of all research in the country, including 53 percent of all basic research, and they help keep America at the forefront of the 21st century economy. The Federal Government has recognized the importance of university research by providing roughly 60 percent of all academic R&D funding. American academic research has benefited from the fact that the US remains a top magnet for the world’s best and brightest students and graduates 16 percent of all PhDs worldwide in scientific and technical fields. -

2018-19 Almanac

2018-19 AUBURN SWIMMING & DIVING ALMANAC TABLE OF CONTENTS QUICK FACTS INFORMATION Location .............................................................. Auburn, Ala. Table of Contents/Quick Facts .............................................................................................................................1 Founded ................................................................Oct. 1, 1856 2018-19 Rosters ...........................................................................................................................................................2 Enrollment ......................................................................29,776 2018-19 Schedule ......................................................................................................................................................3 Nickname .........................................................................Tigers COACHING STAFF School Colors .................Burnt Orange and Navy Blue Head Coach Gary Taylor ....................................................................................................................................4-5 Facility ......James E. Martin Aquatics Center (1,000) Diving Coach Jeff Shaffer.................................................................................................................................. 6-7 Affiliation .....................................................NCAA Division I Assistant Coach Michael Joyce ...........................................................................................................................8 -

125 YEARS of AUBURN WOMEN Worth Celebrating

MAGAZINE / FALL 2017 Celebrating FALL 2017 Auburn Magazine 1 All the World’s a Stage Formed in 1913, the Auburn Players included women students in its productions in 1919 and theater became a formal department in 1925. See below for the 2017-18 schedule; for tickets, visit cla.auburn.edu/theatre/ or call (334) 844-4154. Antigone by Jean Anouilh, adapted by Lewis Galanti Directed by Daydrie Hague September 2017 God of Carnage by Yasmina Reza Directed by Scott Phillips October 2017 A Civil War Christmas by Paula Vogel Directed by Tessa Carr November 2017 Chicago Music by John Kander, lyrics by Fred Ebb, book by Ebb and Bob Fosse Directed by Chris Qualls February 2018 Dance Concert Conceived and directed by Adrienne Wilson and Jeri Dickey March 2018 Mr. Burns, A Post-Electric Play by Anne Washburn Directed by Chase Bringardner April 2018 (Photo by Jeff Etheridge) 2 ALUMNI.AUBURN.EDU FALL 2017 Auburn Magazine 3 FROM THE PRESIDENT THANKS TO THE AUBURN FAMILY for the kind and gracious welcome you’ve extended to Janet and me. Being at Auburn is the opportunity of a Famillifetime, and we will work hard to be worthy y Familof the confidence you’ve placed in us. y I’m a plant pathologist by training, so I’ve focused on keeping the plants in my care healthy and growing. I hope to apply that same focus to Auburn and, with the help of the Auburn Family, make this great institution even stronger. Even in the short time I’ve been here, it’s clear to me that the strength of this university is the direct result of the quality of the faculty, staff and alumni. -

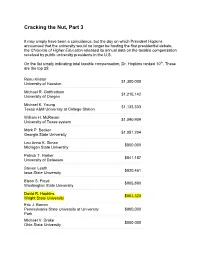

Cracking the Nut, Part 3

Cracking the Nut, Part 3 It may simply have been a coincidence, but the day on which President Hopkins announced that the university would no longer be hosting the first presidential debate, the Chronicle of Higher Education released its annual data on the taxable compensation received by public university presidents in the U.S. On the list simply indicating total taxable compensation, Dr. Hopkins ranked 10th. These are the top 25: Renu Khator $1,300,000 University of Houston Michael R. Gottfredson $1,215,142 University of Oregon Michael K. Young $1,133,333 Texas A&M University at College Station William H. McRaven $1,090,909 University of Texas system Mark P. Becker $1,051,204 Georgia State University Lou Anna K. Simon $850,000 Michigan State University Patrick T. Harker $841,187 University of Delaware Steven Leath $820,461 Iowa State University Elson S. Floyd $805,880 Washington State University David R. Hopkins $803,320 Wright State University Eric J. Barron Pennsylvania State University at University $800,000 Park Michael V. Drake $800,000 Ohio State University James P. Clements $775,160 Clemson University Mark S. Schlissel $772,500 University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Robert E. Witt $765,000 University of Alabama system Robert A. Easter $763,915 University of Illinois system E. Gordon Gee $763,175 West Virginia University John C. Hitt $748,830 University of Central Florida Robert L. Barchi $742,509 Rutgers University at New Brunswick Timothy Michael Wolfe $734,083 University of Missouri system Stuart R. Bell $730,000 University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa Robert L. -

Iowa State University Traditions

Dear Iowa State University Graduates and Guests: Congratulations to all of the Spring 2015 graduates of Iowa State University! We are very proud of you for the successful completion of your academic programs, and we are pleased to present you with a degree from Iowa State University recognizing this outstanding achievement. We also congratulate and thank everyone who has played a role in the graduates’ successful journey through this university, and we are delighted that many of you are here for this ceremony to share in their recognition and celebration. We have enjoyed having you as students at Iowa State, and we thank you for the many ways you have contributed to our university and community. I wish you the very best as you embark on the next part of your life, and I encourage you to continue your association with Iowa State as part of our worldwide alumni family. Iowa State University is now in its 157th year as one of the nation’s outstanding land-grant universities. We are very proud of the role this university has played in preparing the future leaders of our state, nation and world, and in meeting the needs of our society through excellence in education, research and outreach. As you graduate today, you are now a part of this great tradition, and we look forward to the many contributions you will make. I hope you enjoy today’s commencement ceremony. We wish you all continued success! Sincerely, Steven Leath President of the University TABLE OF CONTENTS The Official University Mace ........................................................................................................... 3 The Presidential Chain of Office .................................................................................................... -

June 26, 2012 President Barack Obama the White House 1600

June 26, 2012 President Barack Obama The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave Washington, D.C. 20500 Sen. Harry Reid Sen. Mitch McConnell Senate Majority Leader Senate Republican Leader 522 Hart Senate Office Building 317 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 Hon. John Boehner Hon. Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House Democratic Leader H-232, US Capitol H-204, US Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Mr. President, Majority Leader Reid, Republican Leader McConnell, Speaker Boehner, and Democratic Leader Pelosi: As leaders of universities educating the creators of tomorrow’s scientific breakthroughs, we call on you to address a critical threat to America’s preeminence as a global center of innovation and prosperity: our inability under current United States immigration policy to retain and benefit from many of the top minds educated at our universities. From the industrial revolution to today’s information age, the United States has led the world in creating the inventions and ideas that drive economic prosperity. America’s universities are responsible for 36 percent of all research in the country, including 53 percent of all basic research, and they help keep America at the forefront of the 21st century economy. The Federal Government has recognized the importance of university research by providing roughly 60 percent of all academic R&D funding. American academic research has benefited from the fact that the US remains a top magnet for the world’s best and brightest students and graduates 16 percent of all PhDs worldwide in scientific and technical fields. -

First Friday Breakfast Club News

MAY 2012 First Friday VOLUME 17 News & Views ISSUE 5 THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER GAY CIVIL EQUALITY COMES WITH A GUARANTEE OF THE by Jonathan Wilson FIRST FRIDAY I know the outcome of the debate over gay civil equality, including marriage. I know it for BREAKFAST CLUB, INC. sure. We win and, in doing so, everyone wins. The rapidity with which we are approaching that outcome has thus far been remarkable, and the pace will only accelerate. There are several coa- INSIDE lescing reasons. First, unlike most other minority groups, gay men and lesbians have blood ties -- inseverable Steven Leath by Bruce blood ties -- into the majority. I know; I know. I’ve heard the horror stories about parents reject- 2 Carr ing their children over this issue. They are the distinct minority of parents; they are violating the laws of the Universe; and, in time, they too will come around (if they don’t die first). The vast Helping Good Schools majority of parents embrace their LGBT children (once they know), as do the siblings, the aunts, Become Great Schools by 2 the uncles, the cousins, the children, and in my case, the grandchildren. Those are powerful mul- Sen. Matt McCoy tiples; you do the political math. There is a threshold beyond which there’s no turning back, and we’ve crossed it. Second, gay and lesbian citizens who have served in the US armed forces from the begin- ning of the Republic, can now serve openly. The equal willingness to die, openly, for the protec- Briefs & Shorts 3 tion of our rights and freedoms, makes a compelling case for those rights and freedoms being equal as well. -

College & University Presidents Call for U.S. to Uphold and Continue DACA

College & University Presidents Call for U.S. to Uphold and Continue DACA Story Date: November 21, 2016; download December 1, 2016 Higher education leaders cite “moral imperative” and “national necessity” in supporting Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. As of Nov. 30 at 9 a.m. PST, more than 400 college and university presidents from public and private institutions across the U.S. have signed statement offering to meet with U.S. leaders on the issue. Signatories are listed below and the list will be updated on an ongoing basis. The presidents are urging business, civic, religious and non- profit sectors to join them in supporting DACA and undocumented immigrant students. College and university presidents can still sign the statement. For more information, contact [email protected]. Statement in Support of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Program and our Undocumented Immigrant Students The core mission of higher education is the advancement of knowledge, people, and society. As educational leaders, we are committed to upholding free inquiry and education in our colleges and universities, and to providing the opportunity for all our students to pursue their learning and life goals. Since the advent of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program in 2012, we have seen the critical benefits of this program for our students, and the highly positive impacts on our institutions and communities. DACA beneficiaries on our campuses have been exemplary student scholars and student leaders, working across campus and in the community. With DACA, our students and alumni have been able to pursue opportunities in business, education, high tech, and the non-profit sector; they have gone to medical school, law school, and graduate schools in numerous disciplines. -

Department of Entomology Newsletter

John Clarke III Named Distinguished Alumnus John Lyell Clarke III (Ph.D. 1988) was presented with the ISU Distinguished Alumnus Award by the Alumni Association. Clarke has worked for more than 25 years in the entomology field, including 23 with The Clarke Group, Inc., a global environmental products and services company. He began his career in 1986 as a mosquito con- trol consultant, and then went on to serve as vice president, president, and chief executive officer upon his father’s retirement in 1996. Clarke has furthered his father’s vision of mosquito control with a focus on public health and sustainability. The Clarke Group is an environmentally friendly company that succeeded in creating an organic larvicide. In conjunction with Dow AgroSciences, Clarke introduced Natular, the first reduced-risk larvicide. Natular is 15 times less toxic than alter- Steven Leath (ISU President), John Clarke III, and natives and can be applied at use rates two to Jeffery Johnson (ISU Alumni Association President) Continued on page 13 Larry Pedigo First Legend of Entomology The new Plant-Insect Ecosystems (PI-E) Legends of Entomol- ogy Award recognizes entomologists who have been legends and mentors. Larry Pedigo was selected to be the first ESA P-IE “Legend of Entomology” at the ESA meeting in Knoxville, TN. Larry has been a national leader in IPM for more than 30 years. He led the development and use of economic injury levels, and his approach has been the primary method used in the U.S. and abroad. Pedigo also was an early leader in sampling method- ologies for agricultural pests, co-editing Handbook of Sampling Methods for Arthropods in Agriculture in 1994. -

2013 Graduates of Iowa State University!

Dear Iowa State University Graduates and Guests: Congratulations to all of the Spring 2013 graduates of Iowa State University! We are very proud of you for the successful completion of your academic programs, and we are pleased to present you with a degree from Iowa State recognizing this outstanding achievement. We also congratulate and thank everyone who has played a role in the graduates’ successful journey through Iowa State, and we are delighted that many of you are here for this ceremony to share in their recognition and celebration. We have enjoyed having you as students at Iowa State University, and we thank you for the many ways you have contributed to our university and community. I wish you the very best as you embark on the next part of your life, and I encourage you to continue your association with Iowa State as part of our worldwide alumni family. Iowa State University is now in its 155th year as one of the nation’s outstanding land-grant universities. We are very proud of the role this university has played in preparing the future leaders of our state, nation and world, and in meeting the needs of our society through excellence in education, research and outreach. As you graduate today, you are now a part of this great tradition, and we look forward to the many contributions you will make. I hope you enjoy today’s commencement ceremony. We wish you all continued success! Sincerely, Steven Leath President of the University TABLE OF CONTENTS The Official University Mace ........................................................................................................... 3 The Presidential Chain of Office .................................................................................................... -

August 31, 2015 the Honorable Arne

August 31, 2015 The Honorable Arne Duncan U.S. Department of Education 400 Maryland Avenue, SW Washington, DC 20202 Dear Secretary Duncan: As college and university leaders, we appreciate the U.S. Department of Education’s responsiveness to concerns from the higher education community about a post-secondary rating system. Moreover, we support the Department’s recent announcement that it is instead focusing on the development of consumer-focused tools with newly available data. This effort could benefit students and their families, policymakers, and the public by providing them with new comparison tools and additional information on post-secondary institutions. That is why we are writing you about the Student Achievement Measure (SAM), a voluntary web-based tool that allows institutions to show the progress and graduation of significantly more students than the federal graduation rate. We know you share our belief that the most accurate data available should be used in order for these new tools to be effective and meaningful. Federal graduation rates as reported through the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) are a key piece of data likely under consideration for the new reporting tool. However, the commonly used federal graduation rate is limited to the success of first-time, full-time college students who graduate from their original institution. This has led to a misrepresentation of institutional performance because the federal rate does not account for the success of all students – particularly those students who attend multiple institutions. This month a report from the National Student Clearinghouse revealed that more than one- third of the 3.8 million first-time, full-time students who entered college in 2008 transferred at least once within six years and nearly half of those students changed institutions multiple times. -

2012 Graduates of Iowa State University!

Dear Iowa State University Graduates and Guests: Congratulations to all of the Fall 2012 graduates of Iowa State University! We are very proud of you for the successful completion of your academic programs, and we are pleased to present you with a degree from Iowa State recognizing this outstanding achievement. We also congratulate and thank everyone who has played a role in the graduates’ successful journey through Iowa State, and we are delighted that many of you are here for this ceremony to share in their recognition and celebration. We have enjoyed having you as students at Iowa State University, and we thank you for the many ways you have contributed to our university and community. I wish you the very best as you embark on the next part of your life, and I encourage you to continue your association with Iowa State as part of our worldwide alumni family. Iowa State University is now in its 154th year as one of the nation’s outstanding land-grant universities. We are very proud of the role this university has played in preparing the future leaders of our state, nation and world, and in meeting the needs of our society through excellence in education, research and outreach. As you graduate today, you are now a part of this great tradition, and we look forward to the many contributions you will make. I hope you enjoy today’s commencement ceremony. We wish you all continued success! Sincerely, Steven Leath President of the University TABLE OF CONTENTS The Official University Mace ........................................................................................................... 3 The Presidential Chain of Office ....................................................................................................