Time and Space in the Baseball Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National League News in Short Metre No Longer a Joke

RAP ran PHILADELPHIA, JANUARY 11, 1913 CHARLES L. HERZOG Third Baseman of the New York National League Club SPORTING LIFE JANUARY n, 1913 Ibe Official Directory of National Agreement Leagues GIVING FOR READY KEFEBENCE ALL LEAGUES. CLUBS, AND MANAGERS, UNDER THE NATIONAL AGREEMENT, WITH CLASSIFICATION i WESTERN LEAGUE. PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE. UNION ASSOCIATION. NATIONAL ASSOCIATION (CLASS A.) (CLASS A A.) (CLASS D.) OF PROFESSIONAL BASE BALL . President ALLAN T. BAUM, Season ended September 8, 1912. CREATED BY THE NATIONAL President NORRIS O©NEILL, 370 Valencia St., San Francisco, Cal. (Salary limit, $1200.) AGREEMENT FOR THE GOVERN LEAGUES. Shields Ave. and 35th St., Chicago, 1913 season April 1-October 26. rj.REAT FALLS CLUB, G. F., Mont. MENT OR PROFESSIONAL BASE Ills. CLUB MEMBERS SAN FRANCIS ^-* Dan Tracy, President. President MICHAEL H. SEXTON, Season ended September 29, 1912. CO, Cal., Frank M. Ish, President; Geo. M. Reed, Manager. BALL. William Reidy, Manager. OAKLAND, ALT LAKE CLUB, S. L. City, Utah. Rock Island, Ills. (Salary limit, $3600.) Members: August Herrmann, of Frank W. Leavitt, President; Carl S D. G. Cooley, President. Secretary J. H. FARRELL, Box 214, "DENVER CLUB, Denver, Colo. Mitze, Manager. LOS ANGELES A. C. Weaver, Manager. Cincinnati; Ban B. Johnson, of Chi Auburn, N. Y. J-© James McGill, President. W. H. Berry, President; F. E. Dlllon, r>UTTE CLUB, Butte, Mont. cago; Thomas J. Lynch, of New York. Jack Hendricks, Manager.. Manager. PORTLAND, Ore., W. W. *-* Edward F. Murphy, President. T. JOSEPH CLUB, St. Joseph, Mo. McCredie, President; W. H. McCredie, Jesse Stovall, Manager. BOARD OF ARBITRATION: S John Holland, President. -

Strat-O-Matic Review

• STRAT-O-MATIC Devoted exclusively to the Strat-O-Matic Game Fan, REVIEW with the consent of the Strat-O-Matic Game Co. X*~;':ir:**::::;'ri,.::;'r::'r:*:J;;",.:::::;'r:i,:::;'::!,:::',.::t,:t",.,.:::!.:::,,::*::,,;:**:;.:*:'':::''':**:::'',::*:;:::1: f: ~ f: VOL. V-10, December, 1975 45¢ ~ x x x x **************************************** Eight Old-Timer Teams To Be Added! First the I'badll news. The Strat-O-Matic Game Co. won't be putting out six Old-Timer baseball teams from the period 1920-1939. Now the good news. Instead, it will be putting out eight Old-Timer teams From that period! Because the recent poll conducted in the Review showed a heavy concentrat- ion of votes for two New York Yankee teams (1921 and 1936) and because, after the first three teams, the voting was extremely close, S-O-M creator Harold Richman has decided on eight teams instead of the planned six. When the Review editors last talked with the game company, Richman was researching the eight teams and prepar.ing Fielding and running ratings. The newest set of Old-Timer teams will be available when the 1976 baseball cards come out in the early spring. Now, which eight teams will be added to the growing list of Old-Timer card sets already available? Here are the eight that the readers picked via the poll and the percentage (out of 90 votes) that each received: 1. 1934 Detroit Tigers - 72.2%. 2. 1927 Pittsburgh Pirates - 55.6%. 5. (tie) 1936 New York Yankees, 3. 1929 Chicago Cubs - 53.3% 40%. 4. 1921 New York Yankees - 42.2%. -

Female Sportswriters of the Roaring Twenties

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications THEY ARE WOMEN, HEAR THEM ROAR: FEMALE SPORTSWRITERS OF THE ROARING TWENTIES A Thesis in Mass Communications by David Kaszuba © 2003 David Kaszuba Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2003 The thesis of David Kaszuba was reviewed and approved* by the following: Ford Risley Associate Professor of Communications Thesis Adviser Chair of Committee Patrick R. Parsons Associate Professor of Communications Russell Frank Assistant Professor of Communications Adam W. Rome Associate Professor of History John S. Nichols Professor of Communications Associate Dean for Graduate Studies in Mass Communications *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ABSTRACT Contrary to the impression conveyed by many scholars and members of the popular press, women’s participation in the field of sports journalism is not a new or relatively recent phenomenon. Rather, the widespread emergence of female sports reporters can be traced to the 1920s, when gender-based notions about employment and physicality changed substantially. Those changes, together with a growing leisure class that demanded expanded newspaper coverage of athletic heroes, allowed as many as thirty-five female journalists to make inroads as sports reporters at major metropolitan newspapers during the 1920s. Among these reporters were the New York Herald Tribune’s Margaret Goss, one of several newspaperwomen whose writing focused on female athletes; the Minneapolis Tribune’s Lorena Hickok, whose coverage of a male sports team distinguished her from virtually all of her female sports writing peers; and the New York Telegram’s Jane Dixon, whose reports on boxing and other sports from a so-called “woman’s angle” were representative of the way most women cracked the male-dominated field of sports journalism. -

Weekly Notes 082417

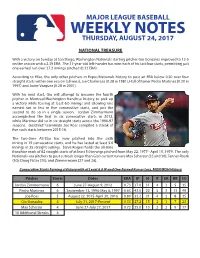

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES THURSDAY, AUGUST 24, 2017 NATIONAL TREASURE With a victory on Sunday at San Diego, Washington Nationals starting pitcher Gio Gonzalez improved to 12-5 on the season with a 2.39 ERA. The 31-year-old left-hander has won each of his last four starts, permitting just one earned run over 27.2 innings pitched (0.33 ERA). According to Elias, the only other pitchers in Expos/Nationals history to post an ERA below 0.50 over four straight starts within one season (all wins), are Charlie Lea (0.28 in 1981), Hall of Famer Pedro Martinez (0.30 in 1997) and Javier Vazquez (0.28 in 2001). With his next start, Gio will attempt to become the fourth pitcher in Montreal/Washington franchise history to pick up a victory while tossing at least 6.0 innings and allowing one earned run or less in fi ve consecutive starts, and just the second to do so in a single season. Jordan Zimmermann accomplished the feat in six consecutive starts in 2012, while Martinez did so in six straight starts across the 1996-97 seasons. Gonzalez’ teammate Joe Ross compiled a streak of fi ve such starts between 2015-16. The two-time All-Star has now pitched into the sixth inning in 19 consecutive starts, and he has lasted at least 5.0 innings in 25 straight outings. Steve Rogers holds the all-time franchise mark of 62 straight starts of at least 5.0 innings pitched from May 22, 1977 - April 15, 1979. -

BSI-Anthology-For-The-Web.Pdf

Books Sandwiched In 1956-2016 Book/Topic Author Date Reviewer Title BSI 1956 The Menninger Story Walker Winslow 10/2/1956 Dr. John Romano University of Rochester Department of Medicine, Professor The Accident Dexter Masters 10/9/1956 Doris Savage Librarian The Right to Know Kent Cooper 10/16/1956 Paul Miller Gannett Newspapers, Executive Vice President The Scrolls from the Dead Sea 10/23/1956 Rabbi Joel Dobin Rabbi A New Respect for the American Indian in Books for Children 10/30/1956 Julia L. Sauer Rochester Public Library, Head of Children's Work African Interpretations in Recent Novels 11/6/1956 Dr. William Diez University of Rochester, Professor From Pymalion to My Fair Lady 11/13/1956 Dr. Katharine Killer University of Rochester, Professor The Will of God Leslie Weatherhead 11/20/1956 Dr. Murray Cayley Clergy Rochester: The Quest for Quality 11/27/1956 Dr. Arthur May University of Rochester, Professor Brandies, Free Man's Life Alpheus T. Mason 12/4/1956 Sol Linowitz Attorney BSI 1957 TBA TBA 10/1/1957 Peter Barry Mayor Music in American Life Jaques Barzun 10/8/1957 Dr. Howard Hanson Fashions in Biography 10/15/1957 Dr. Ruth Adams Mr. Lippmann's Terrifying Book 10/22/1957 Dr. Justin W. Nixon The Lion and the Throne Catherine D. Bowen 10/29/1957 Daniel G. Kennedy Voice of Israel Abba Eban 11/5/1957 Rabbi Philip Bernstein Freedom or Secrecy James R. Wiggins 11/12/1957 Clifford E. Carpenter Shakespeare in America 11/19/1957 Dr. Wilbur E. Dunkel The Testimony of the Spade Geoffrey Bibby 11/26/1957 James M. -

"Babe" Ruth 1922-1925 H&B

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S November 10, 2016 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Rare George "Babe" Ruth 1922-1925 H&B "Kork Grip" Pro Model Bat Ordered For 1923 Opening Day of Yankee Stadium!46 $ 25,991.25 2 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ray Demmitt (St. Louis) Team Variation-- SGC 50 VG-EX 4 12 $ 3,346.00 3 1909-11 T206 White Borders Christy Mathewson (White Cap) SGC 60 EX 5 11 $ 806.63 4 1909-11 T206 White Borders Christy Mathewson (White Cap) SGC 55 VG-EX+ 4.5 11 $ 627.38 5 1909-11 T206 White Borders Christy Mathewson (Portrait) PSA VG-EX 4 15 $ 1,135.25 6 1909-11 T206 White Borders Christy Mathewson (Dark Cap) with Sovereign Back--PSA VG-EX 4 13 $ 687.13 7 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Bat On Shoulder) Pose--PSA Poor 1 9 $ 567.63 8 1909-11 T206 White Borders Larry Doyle (with Bat) SGC 84 NM 7 4 $ 328.63 9 1909-11 T206 White Borders Johnny Evers (Batting, Chicago on Shirt) SGC 70 EX+ 5.5 7 $ 388.38 10 1909-11 T206 White Borders Frank Delehanty SGC 82 EX-MT+ 6.5 6 $ 215.10 11 1909-11 T206 White Borders Joe Tinker (Bat Off Shoulder) SGC 60 EX 5 11 $ 274.85 12 1909-11 T206 White Borders Frank Chance (Yellow Portrait) SGC 60 EX 5 9 $ 274.85 13 1909-11 T206 White Borders Mordecai Brown (Portrait) SGC 55 VG-EX+ 4.5 5 $ 286.80 14 1909-11 T206 White Borders John McGraw (Portrait, No Cap) SGC 60 EX 5 10 $ 328.63 15 1909-11 T206 White Borders John McGraw (Glove at Hip) SGC 60 EX 5 10 $ 262.90 16 1909-11 T206 White Border Hall of Famers (3)--All SGC 30-60 8 $ 418.25 17 1909-11 T206 White Borders Nap Lajoie SGC 40-50 Graded Trio 21 $ 776.75 -

We're Hatching Jayhawk Fun at the Kansas

28 Contents Established in 1902 as The Graduate Magazine FEATURES In the Abstract 28 He’s arguably the most brilliant analyst baseball has ever known. But if you think Bill James’ books are all about stats and formulas, you know only half the story. BY STEVEN HILL Click Down Memory Lane 32 A graduate student’s dream project will vault KU’s treas- ured history out of the archives and onto the World Wide COVER Web. Kansas Alumni presents a sneak peak at the past. Untold Fortune BY CHRIS LAZZARINO 20 Photographer Pok Chi Lau has spent 25 years documenting the Asian immigrant experience. A Headliner She started her journalism career ruffling feathers at new book showcases his work. 36 KU. Kelly Smith Tunney has since achieved several firsts that propelled her to the upper ranks of the world’s BY STEVEN HILL largest news service. Cover photograph by Aaron Delesie BY KRISTIN ELIASBERG 32 Volume 100, No. 5, 2002 My husband checked the inner pocket of his jacket to make sure the Lift the Chorus tickets were still there, only to discover they were gone! Panic stricken, we made our way through the crowd to a gentle- man holding a bullhorn and inquired if A history of peace mother, Muriel (Frances) Wolfe anyone had turned in our tickets. No [a member of the Class of tickets had been turned in. Your Oread Encore 1925]. I showed the picture to We walked away with our hearts in essay about the peace my mother and she agreed that our stomachs. About that time, a young pipes tradition at gradua- this was a picture of my grand- gentlemen approached us saying, “I tion [“Token gestures,” mother. -

ATHLETICS Copy.Pages

! QUOTES ON PHYSICAL EDUCATION & ATHLETICS ! ! Don’t permit the pressure to exceed the pleasure. ! —Joe Maddon I run like a girl. Try to keep up. ! —T-Shirt Slogan An amateur practices until he can do a thing right, a professional until he can’t do it wrong ! --Percy C. Buck When you are not practicing, remember, someone somewhere is practicing, and when you meet him he will win. ! --Ed Macauley When you are satisfied you’ve played your best game, you probably have. ! --Unknown You have failed only when you have failed to try. ! --Unknown How a man plays the game shows something of his character; how he loses shows all of it. —Tribune (Camden ! County, Georgia) If I don’t practice one day, I know it; if I don’t practice two days, the critics know it; and if I don’t practice for three days, everyone knows it. ! --Peter Tchaikovsky Those who think they have not time for bodily exercise will sooner or later have to find time for illness. —Edward Stanley, Earl ! of Derby ! - !1 - Track is kind of like football. Sure, there’s no ball and no shoulder pads, and noth- ing in your way except the string across the finish line. But you can demolish a kid just as much by beating him in a race as by plowing him under on a football field. ! --Jerry Spinelli Pain is weakness working its way out of your body. ! --Unknown The breakfast of champions is not cereal; it’s the opposition. ! --Nick Seitz Practice does not make perfect. -

Frozen Moments in the Interior Stadium: Style in Contemporary “Prosebalf

Order Number 9401186 Frozen moments in the interior stadium: Style in contemporary “prosebalF Hunt, Moreau Crosby, D.A. Middle Tennessee State University, 1993 UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Anti Alb or, M I 48106 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Frozen Moments in the Interior Stadium: Style in Contemporary "Proseball" Crosby Hunt A dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of Middle Tennessee State University August 1993 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Frozen Moments in the Interior Stadium: Style in Contemporary "Proseball" APPROVED! Graduate Committee: Major Professor Reader Head of Departmen Dean of thje Graduate School Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract Frozen Moments in the Interior Stadium: Style in Contemporary "Proseball" Crosby Hunt Writing about baseball has never been so popular as it is presently, causing one scholar to refer to "the current boom" in publishing. Most of the analysis of this body of work has centered on novels, but it is apparent that other forms of baseball writing are rhetorically as interesting as fiction. After summarizing some of the major critical works on baseball fiction, this study seeks to rectify certain omissions in the field of what Donald Hall calls "proseball." Included in this dissertation are studies of three player- autobiographies: Ted Williams * Mv Turn at Bat. Jim Brosnan’s The Long Season, and Jim Bouton*s Ball Four, in chapter two. Also covered, in chapter three, are essays by Roger Angell, John Updike, and Jonathan Schwartz, focusing on what Schwartz calls "frozen moments" in what Angell calls "the interior stadium." Chapter four provides an analysis of Don DeLillo's recent postmodern novella, Pafko at the Wall. -

October 2015 Newsletter

October find your story 2015 Columbus Day hours On Monday, October 12 we will be Congressman Steve Israel talks open from 1 to 5 p.m. FOL Paperback Swap The Friends of the Library’s popu- The Global War on Morris lar Paperback Swap returns on Sat- urday, October 17 from 1 to 4 p.m. On Tuesday, October 13 at 7:30 to them. Bring your gently used adult, teen p.m., the Friends of the Library wel- “Spirited and funny... writing and children’s paperbacks to the comes Congressman Steve Israel, who in the full-tilt style of Carl Hiaasen, Lapham meeting room for a free, will discuss his novel, The Global War Israel... skewers his way through one friendly event where hundreds of on Morris. gaffe after another in the fight against patrons swap thousands of books. In The Global War on Morris, domestic terrorism. Imagine It’s a We will accept hardcover children’s Israel has written a witty political sat- Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World with a books including board books. No ire ripped from the headlines. Morris soupcon of al-Qaeda.” --Ron Charles, more than 20 books per person and Feldstein is a pharmaceutical sales- The Washington Post no books accepted in advance. We man living and working in western “Rep. Steve Israel reveals his stop accepting items at 3:30 p.m. Long Island who loves the Mets, loves inner Jon Stewart in his debut novel.” Browsers are welcome! his wife and loves things just the way --New York Daily News they are. -

A Needed Change in the Rules of Baseball Lewis Kurlantzick University of Connecticut School of Law

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Faculty Articles and Papers School of Law 1992 A Needed Change in the Rules of Baseball Lewis Kurlantzick University of Connecticut School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Legal Remedies Commons Recommended Citation Kurlantzick, Lewis, "A Needed Change in the Rules of Baseball" (1992). Faculty Articles and Papers. 170. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers/170 +(,121/,1( Citation: 2 Seton Hall J. Sport L. 279 1992 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 15 17:02:14 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. A NEEDED CHANGE IN THE RULES OF BASEBALL Lewis Kurlantzick* I. INTRODUCTION Ideal accounts of modern sport paradigmatically portray it as ac- tivity involving the quest for the highest level of performance.1 If the exercise and development of physical skills and the achievement of mastery over one's body are among the intrinsic pleasures connected with sports, the challenge of a contest enhances these skills and heightens this sense of mastery. The athletic interaction of a compet- itive contest appears to mobilize energies beyond what is possible in noncompetitive situations. If we hope to achieve what the philoso- pher Paul Weiss refers to as "the excellence of the body,"' 2 we need others as opponents. One implication of this paradigm is that if the fastest runners or swimmers are barred from competition for some irrelevant reason, the victory or record achieved is devalued.3 No gen- uine sports fan nor any athletic participant in a championship con- test, who values his own performance and the process for determin- ing a victor, looks with favor on the needless disqualification of a critical member of the opposing team in an important game. -

R. Plapinger Baseball Books

R. PLAPINGER BASEBALL BOOKS (#294) BASEBALL NON-FICTION CATALOG #42 SPRING/SUMMER 2006 P.O. Box 1062, Ashland, OR 97520 (541) 488-1220 • [email protected] $4.00 1 Thank You For Requesting This Catalog. Please Read These Notes Before You Begin. Books are listed in alphabetical order by author’s last name. All books are hardback unless indicated PB which means a “pocket size” paperback or TP which means a larger format paperback. “Orig.” means a book was never published in hardback, or was first published as a paperback. “Sim w. hb” means that the hard and paper covered editions were published simultaneously. All books are First Editions to the best of my knowledge, unless indicated reprint (rpt) or later printing (ltr ptg). Books and dust jacket grading: Mint (mt) (generally used only for new books); Fine (fn); Very Good (vg); Good (g) (this is the average condition for a used book); Fair (fr); Poor (p). Grade of dust jacket (dj) precedes the grade of the book (dj/bk). If a book has no dj: (ndj). PC indicates a photo or picture cover on the book itself (not the jacket). When I know a dj was never issued, I indicate: “as iss.” In addition to the grades above “+” and “-” are used to indicate minor variations in condition. Specific defects to a book or dj are noted, as are ex-library (x-lib) and book club (BC) editions. X-lib books generally exhibit some, or all of the following traits: front or rear flyleaf removed, glue and/or tape stains on covers and/or flyleaves, stamps on edges or flyleaves, library pocket.