Invited paper presented at the 6th African Conference of Agricultural Economists, September 23-26, 2019, Abuja, Nigeria

Copyright 2019 by [authors]. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies.

Food security status of rice marketers’ households in Niger state,

Nigeria: a gender-based analysis

*ENIOLA OLUWATOYIN OLORUNSANYA1.YAKUBU MOHAMMED AUNA2, AYOTUNDE.OLUWATUNBO OLORUNSANYA3, ARE KOLAWOLE4 AND ALIMI FUNSO LAWAL1

1Department of Agricultural Economics, Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria

2Dept. of Crop Production Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai, Niger, State

3Dept. of Animal Production, Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria

4Dept. of Political Science, Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria

*Author of Corespondence : [email protected]

Abstract:

Food insecurity is presently a global threat to human existicence. Therefore, a gender based economic analysis of rice marketing for food security was carried out in Niger State using 430 representative rice marketers’ households. The survey data were analysed using descriptive statistics, food security indeces and logistic regression model. Results show that the rice marketers are mostly females (74%) with mean age of 39 years and a mean household size of 7 members against 41 years for male marketers and 8 household members. The mean years of schooling are also 4 and 8 years for female and male marketers respectively. Furthermore, the average per capita daily calories available in the study area are 1980.36Kcal and 2,383Kcal for male and female marketers’ households respectively. Using the recommended calorie requirement of 2470Kcal, 138 rice marketer’s households were food secure and 282 were food insecure. The identified determinants of food security status for all households include gender of the marketers, years of schooling, adjusted household size, and net profit.. Improved rice marketing system, manageable household size as well as improved literacy level are required for attainment of food security in the state. Keywords: Rice marketing, gender analysis, marketing margin, marketing efficiency, marketing performance.

1.Introduction

Over the years problems of food insecurity have been a global phenomenon and its major causes are climate change, uncontrollable increase in world’s population, changing human tastes, water scarcity and farming households’peculiar problems (Breene, 2017). Nord et al., (2009) defines food insecurity as the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways without resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing, or other coping strategies. It does mean not being food secure and it could be a chronic or transitory problem. In chronic food insecurity, there is a continuous inadequate diet and nutrition caused by households inability to acquire food either by purchase or own production (Food and Agricultural Organisation) (FAO), (2008). On the other hand, transitory food insecurity results from a temporary decline in household income or a combination of factors such as seasonal fluctuations in food availability, food prices and income, which themselves may result in seasonal fluctuations in individual nutritional status (FAO, 2008). A household with problem coping with seasonality in food availability, food prices and income are considered as fragile, while households that can weather such periodic crisis are considered as resilient (Agboola, Koroma, and Ikpi, 2004).The focus of the world leaders for decades now has been ensuring food security for all. For instance, the world leaders pledged to eradicate extreme hunger and poverty by 2030 (United Nations Development Project (UNDP), 2017). “Food security on the other hand exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, nutritious and culturally adequate food to meet their dietary needs for active and healthy life” (FAO, 2002). It includes ready availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods and this connotes assured ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways. This rests on the premise that food security depends on availability, accessibility, adequacy and acceptability of food. Availability of food could only be achieved when supply of food grows at par with food demand through either domestic production or importation or combination of the two. The population growth rate in Nigeria in 2017 was 2.28% against the total GDP growth rate of -0.52% per annum (National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), (2017). This has resulted into annual food deficit running into several million metric tonnes and skyrocketing import bills with a continued drain on the country’s foreign exchange reserve (Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) 2016). The effect of the shortfall in the supply and demand for food is felt mostly by low income, resource poor rural dwellers which results in hunger and malnutrition. Despite great efforts to transform Nigeria’s agriculture and huge investment by private and government organisations over the years, rural poverty and food insecurity have persisted. This suggests a need to reconsider current agricultural production, processing and marketing systems to identify new ways of improving them. Tremendous improvement in rice production, processing and marketing will bridge the gap between supply and demand of rice in Nigeria and preserve foreign exchange earnings through reduction in importation and increase in export (FMARD, 2016). The gender connotation to the attainment of food security is also of importance globally and in Nigeria particularly. Gender roles and expectations are often identified as factors hindering the equal right and status of women with adverse consequences that affect life, family, socioeconomic status, health and access to production resources (Mason et al., 2015; Olorunsanya et al., 2012 and Kassie et al., 2012). In each of these areas women worldwide are mostly affected. Thus gender issues cannot be over-emphasised in challenges facing food security in Niger State. Women are important in attainment of food security especially in most developing countries where rural women are involved in small-scale agriculture, supply of farm labour, and provision of food for their households (FAO, 2011). Some of the current aims of national agricultural policy for Nigeria are: (i) attainment of food security, (ii) increase in agricultural production and productivity, and (iii) expansion of exports for foreign exchange earnings and reduction of food imports to protect local production and preserve foreign reserve (FMARD, 2016). The federal government is also developing the value chain of some important agricultural commodities such as rice, cassava, sorghum, cacao and cotton through agricultural transformation agenda and agricultural promotion policy (FMARD, 2016). Although rice is cultivated in almost all the ecological zones in Nigeria, nevertheless import still accounts for a large percentage of rice consumption due to preference for the foreign rice and low supply from the domestic market. In 2016, the estimated demand for rice in Nigeria was put at 6.3 million metric tonnes while domestic supply was only 2.3 million metric tonnes, the short fall was met through importation (FMARD, 2016). This supply-demand gap in rice production in developing countries is as a result of high population growth rate, rapid urbanization and shift in consumer preference in favour of rice (FMARD, (2016); Macauley, (2015) & Sect et al., 2013). Nigeria has huge expanse of potential land area for rice production but only a fraction is under cultivation. Presently an agricultural household in Nigeria holds an average of 2.6 plots at an average of 0.5 hectares in size (NBS, 2016a). If rice must be used as food security crop in Niger state, a multi-faceted approach must be adopted. This study therefore carries out an economic analysis of rice marketing in Niger state for the attainment of food security in the state. The study also measures the level of food security status of the rice marketers’households based on gender as well as identifies the determinants of food security among rice marketers’households in the state.

2.0 Methodology 2.1 Research Location

Niger State is an agrarian state located in the north central zone of Nigeria between latitude 8020'N and 11030'N and longitude 3030'and 7020'E. The landscape consists mostly of wooded savannas and includes the flood plains of the Kaduna River. The state is populated mainly by the Nupe people in the south, the Gwari in the east, the Busa in the west, and Kamberi (Kambari), Hausa, Fulani, Kumuku, and Dakarki (Dakarawa) in the north. Agricultural production and marketing are the major occupation of the people of Niger State and the major crops grown include rice, groundnuts, millet, cowpea, cotton, yams, shea nuts, maize, tobacco, oil palm, cola nuts and sugarcane. Fishing and animal husbandry are also important in the state (Britannica Online Encyclopedia, 2011). The state is stratified into 25 local government areas namely: Agaie, Agwara, Bida, Borgu, Bosso, Chanchaga, Edati, Gbako, Gurara, Katcha, Kontagora, Lapai, Lavun, Magama, Mariga, Mashegu, Mokwa, Munya, Paikoro, Rafi, Rijau, Shiroro, Suleja, Tafa and Wushishi. These LGAs are further compacted into three zones based on socio-political reasons. Rice production and marketing are carried out in all the local government areas of the state.

2.2 Data Source and Sampling Technique

Primary data obtained through interview schedule with the aid of structured questionnaire were used for the study. The questionnaire were administered in all the three agricultural zones of the state using three-stage sampling technique. The first stage entails a random selection of seven local government areas from the three agricultural zones in the state based on proportionality. The second stage involves a random selection of two villages in each of the chosen LGAs to give a total of fourteen villages in all.The final stage consists of a random selection of rice marketers’ households in the seleted villages based on proportionality. A total of four hundred and twenty (420) rice marketers’ households were eventually used for the study.

2.3 Analytical Techniques

The data generated from the survey were analysed using descriptive statistics, marketing margin and efficiency measures as well as food security measures and Logistic regression model. The analytical tools are further deliberated upon as follows:

2.3.1 Marketing margin and marketing efficiency measures

Marketing margin is the difference between the average price paid by consumers for agricultural commodity and the farm gate price (Wohlgenant, 1989). It is as a result of demand and supply factors, marketing costs, and the degree of marketing channel competition. It does reflects aggregate processing and retailing firm behaviour which influences the level and variability of farm prices and may influence the farmer’s share of the consumer food (Wohlgenant,1989). The total marketing margin for an agricultural crop equals the sum of retail and wholesale marketing margin and is specified as follows:

Wholesaler Marketing Margin:

Wholesaler’s Marketing Margin (Mw) = Wholesaler Price (Pw) - Farm Gate Price (Pf) Wholesaler’s Net Marketing Margin = Mw -MCw Where:MCw = Wholesaler marketing cost

Retailers Marketing Margin:

Retailer’s Marketing Margin (Mr) =Retailer’s Price (Pr) -Wholesaler Price (Pw) Retailer’s Net Marketing Margin = Mr -MCr Where: MCr = Retailer’s Marketing Cost

Total Marketing Margin:

Total Marketing Margin (MMT) = Mw +Mr Total Net Marketing Margin: = Pr-Pf The share of farmer, wholesaler and retailer from retail price are calculated as follows: Farmer’s Share (Sf) = Pf/Pr * 100 where: Pf =Farmer’s Price and Pr = Retailer Price. Wholesaler’s Share (Sw) = Pw -Pf / Pr * 100. Where: Pw, Pf and Pr are wholesaler price, farmer price and retailer price respectively. Retailer’s Share (Sr) = Pr -Pw /Pr * 100. Where: Pr,Pw are retailer and wholesaler prices respectively. And Sf, Sw, and Sr are farmer, wholesale and retailer’s share respectively.

ii) Marketing cost coefficient

Marketing Cost Coefficient (MCC) which shows marketing margin as a fraction of retail price is given as: MCC = SL +SP + Sw +Sr = MM/ Pr *100 Where: SL, SP, Sw, Sr are local assembler, processor, wholesaler and retailer’s share respectively. Marketing Cost Coefficient shows the share of final consumers from the total marketing margin of product.

iii) Marketing efficiency measurement using shepherd’s formula

Shepherd’s Index Formula is given as: ME = (V/ I) – 1 Where: ME = Marketing Efficiency Index in Naira per 100Kg bag V = Value of goods sold or consumer’s price in Naira per 100Kg bag I = Total marketing cost in Naira per 100Kg bag. Higher ratio shows higher marketing efficiency and vice versa.

2.3.2 Food security measure:

A household is defined in the study as a group of people living together and eating from the same pot (Olorunsanya, 2009). The data on household size obtained from the survey were adjusted for adult equivalence using the male adult equivalent weight scale provided in Table 1. In measuring the food security status of the households, a minimum acceptable benchmark for healthy living called the food security line for the population was estimated below which a household was considered food insecure.The food security benchmark was obtained using the recommended daily calorie intake of 2470Kcal per capita.

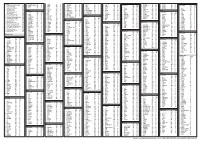

Table 1: Equivalent Male Adult Scale Weights for Determining Adjusted Household Size Age Category

Under 1year 1-4.9 years

Male

0.00 0.25 0.60 0.75 1.00 0.80

Female

0.00 0.20 0.50 0.75

5-9.9years 10-14.9years 15-59.9years 60 and above Source: Falusi, (1985)

0.90 0.65

The household calorie availability was estimated using the food nutrient composition in Table 2 and based on energy content of both produced and purchased food items which represent the total food supply for the households. The per capita calorie daily consumption was obtained by dividing the estimated daily calorie supply by the adjusted household size. The food security indices for the study were obtained using the following formula:

ꢁ

ꢀ = ................................................................................................................................................................(1)

ꢂ

Where: Z = Food Security Index K = Per capita household daily calorie availability R = Recommended household’s daily per capita calorie intake

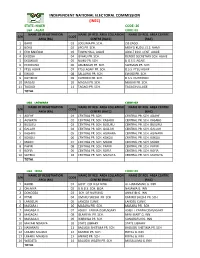

Table 2: FoodNutrient Composition

- Food Item

- Energy Kcal/kg

- Proteins

- Maize

- 3600

- 90

- Rice

- 3500

3500 3300 5500 4000 1500 3400 1100 3200 2250 1320 938

60

Millet and Sorghum Cowpea Groundnut Soybean Cassava (Fresh) Cassava flour Yam (fresh) Yam flour Beef

100 210 230 330 10 20 20 40 147.29 87.98 110

Fish Egg Source: Deville de Goye et al., (1978)

A household is considered to be food secure if its calorie food intake is more than or equal to Z, the estimated benchmark and food insecure if otherwise. Based on the estimated Z, several food security measures were estimated as follows:

The Head Count Ratio (H) which is defined as:

ꢄ

ꢃ = ..............................................................................................................................................................(2)

ꢅ

Where: M= Number of food secure households N= Sampled population The short fall or surplus index, P, which is given as:

1

∑

ꢆ = ꢇ ꢉ=1 ꢈ .................................................................................................................................................(3)

ꢉ

Where m = number of households that are food secure (food surplus index) or food insecure (food short fall index). It measures at the aggregate level, the extent at which the households are below or above the food security line.

ꢈꢊ = ꢋꢉ−ꢂ.......................................................................................................................................................(4)

ꢂ

GJ = is the deficiency or surplus faced by j household XJ = average calorie available to the jth household

2.3.3 The determinants of food security status of rice marketers’ households

The determinants of food security status of the rice marketers’ households were identified using Logit model which is specified as follows: Prob(event) =1/1+e-z where ꢌ = ꢍ0 + ꢍꢎꢏꢎ…………………………………….…………………………………………………………(5) which is the linear combination. The event is equal to one (1) for food secure households and zero (0) otherwise. Xi=vector of explanatory variables and βi are the estimated parameters. The hypothesised explanatory variables are: X1 = a dummy variable specifying the gender of the household head. It is = 1 if the head is a male and 0 otherwise. X2=Cooperative membership. Also a dummy variable and =1 if the household head is a member cooperative society and 0 if otherwise

- of

- a

X3= Adjusted household size measured in adult equivalents X4=Access to credit X5=Years of schooling of the marketers X6=Age of the household heads measured in years X7=Net Profit from rice marketing

3. Results and Discussion 3.1 Characteristics of the rice marketers

This section presents the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the respondents as well as rice marketing information (Table 3).

3.1.1 Gender of the rice marketers

Gender in this study is restricted to sex of the rice marketers that is whether they are males or females. Rice marketing is predominantly carried out by females in the study area,74% of the marketers are females (Table 3). This follows the trends in gender roles in the study area where the males are more involved in rigorous farm activities and their female counterparts in processing and marketing (Olorunsanya and Ugbong, 2014). At the local government level, this pattern prevails except in Wushishi and Kotangora where there are more male rice marketers than female ones. This also follows the culture and belief of the people of these local government areas that put women in confinement. Significant differences exist between local government areas and gender of the marketers (P<0.000).

Table 3: Distribution of the respondents based on gender

Male-Marketers

109 (26)

109 (26)

Female-Marketers

311 (74)

311(74)

Total

420 (100)

420 (100)

Gender

All local governments

Different Local Governments

Lapai Bida

4(1.0) 11(2.6) 1(1.0)

56 (13.3) 51(12) 59(14) 57(13.5) 14(3.3) 22(5.2) 54(12.8)

311(74)

60(14.3) 60(14.3) 60(14.3) 60(14.3) 60(14.3) 60(14.3) 60(14.3)

420 (100)

Paikoro Gbako Wushishi Kotangora Chachanga

Total

3(0.7) 46(10.9) 38(9.0) 6(1.4)

109(26)

Source: Authors’ computation. Figures in parentheses are percentages of total.

3.1.2 Marital status of the rice marketers

Table 4 shows the marital status and the sub-groups of households in the study area. In each of the gender sub-groups, 87% and 88% of the male and female marketers sub-groups are married. No significant differences exist between gender of the marketers and their marital status. This result is in agreement with the findings of Akarue and Ofoegbu (2012) in Udu Local government area of Delta State, Nigeria.

Table 4: Distribution of Respondents Based on Marital Status

- Male-Marketers

- Female-Marketers

- Total

Marital Status