DROIDMAKER George Lucas and the Digital Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRESSING a GALAXY 10/25/05 5:25 PM Page 46

000-000_29.1 DRESSING A GALAXY 10/25/05 5:25 PM Page 46 Dressing a Galaxy The Costumes of Star Wars Patt Diroll “You know, sometimes I even amaze myself.” — Han Solo hat famous line from the first Star Wars film might well serve as the mantra for the imaginative genius who leads the costume design team for George Lucas’s blockbuster space operas. Whipping up duds worn a long time ago by the denizens of galaxies far, far away twould be a daunting challenge for any designer, but for the amazing Trisha Biggar, it is all in a day’s work. “Her ability to manage, move, design, build, locate and scrounge was a rare find,”says Star Wars producer, Rick McCallum. The unflappable Glasgow native takes it all in stride, crediting Lucas’s own vision and hands-on involvement with her success. Having trained at Wimbledon School of Art, Biggar worked in the United Kingdom in noted theater companies such as the Glasgow Citizens’ Theatre and Opera North in Leeds. Her film credits include Silent Scream, Wild West, and The Magdalene Sisters. She has also designed for numerous television series; among them Moll Flanders for which she received a BAFTA nomination for Best Costume Design, and The Young Indiana Jones ANAKIN SKYWALKER AND PADMÉ AMIDALA in Wedding Ensembles, from Attack of the Clones. Photographs courtesy of © 2005 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM, except where noted. All Rights Reserved. Used under authorization. 000-000_29.1 DRESSING A GALAXY 10/25/05 5:25 PM Page 47 Chronicles. However, she was unknown to Lucas and McCallum For an alien species, the costumes proved to be much until she was discovered quite by happenstance. -

Notes De Production

Notes de production Red Tails est un film d’action et d’aventure inspiré par les exploits de la première unité de combat aérien afro-américaine de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Ce film emmène tour à tour le public dans les cockpits des avions de combat au beau milieu des combats aériens, dans les couloirs tendus du Pentagone où les pontes de l’armée débattent du risque de l’utilisation de pilotes noirs au combat, et révèle la camaraderie des jeunes héros de Tuskegee qui servirent leur nation avec bravoure et excellence. C’est un hommage exaltant à un fait réel de l’histoire américaine, raconté dans un style rythmé et passionnant. « C’est l’histoire d’une bande de jeunes hommes qui se retrouvent dans une situation incroyable et qui, malgré les dangers, font un travail extraordinaire et reviennent en héros… Ce sont de vrais chevaliers des temps modernes », raconte George Lucas. Le producteur délégué, George Lucas, a mis 23 ans à développer cette histoire, accompagné au fil du temps des producteurs Rick McCallum et Charles Floyd Johnson, des scénaristes John Ridley et Aaron McGruder, du réalisateur Anthony Hemingway et d’acteurs talentueux incluant Cuba Gooding Jr. (lauréat aux Oscar®), Terrence Howard (nominé aux Oscar®), David Oyelowo et Nate Parker. Dans la tradition des aventures époustouflantes et intrigues passionnantes dont Lucasfilm a le secret, Red Tails peut se vanter d’une production détaillée, d’effets spéciaux high-tech et d’un son à couper le souffle. Red Tails est un hommage passionnant à de véritables héros, un film créé par des centaines de gens talentueux, dont l’équipe de Skywalker Sound et celle d’Industrial Light & Magic qui a supervisé sept studios d’effets spéciaux autour du monde. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Fall 2018 Alumni Magazine

University Advancement NONPROFIT ORG PO Box 2000 U.S. POSTAGE Superior, Wisconsin 54880-4500 PAID DULUTH, MN Travel with Alumni and Friends! PERMIT NO. 1003 Rediscover Cuba: A Cultural Exploration If this issue is addressed to an individual who no longer uses this as a permanent address, please notify the Alumni Office at February 20-27, 2019 UW-Superior of the correct mailing address – 715-394-8452 or Join us as we cross a cultural divide, exploring the art, history and culture of the Cuban people. Develop an understanding [email protected]. of who they are when meeting with local shop keepers, musicians, choral singers, dancers, factory workers and more. Discover Cuba’s history visiting its historic cathedrals and colonial homes on city tours with your local guide, and experience one of the world’s most culturally rich cities, Havana, and explore much of the city’s unique architecture. Throughout your journey, experience the power of travel to unite two peoples in a true cultural exchange. Canadian Rockies by Train September 15-22, 2019 Discover the western Canadian coast and the natural beauty of the Canadian Rockies on a tour featuring VIA Rail's overnight train journey. Begin your journey in cosmopolitan Calgary, then discover the natural beauty of Lake Louise, Moraine Lake, and the powerful Bow Falls and the impressive Hoodoos. Feel like royalty at the grand Fairmont Banff Springs, known as the “Castle in the Rockies,” where you’ll enjoy a luxurious two-night stay in Banff. Journey along the unforgettable Icefields Parkway, with a stop at Athabasca Glacier and Peyto Lake – a turquoise glacier-fed treasure that evokes pure serenity – before arriving in Jasper, nestled in the heart of the Canadian Rockies. -

The Case for Game Design Patterns

Gamasutra - Features - "A Case For Game Design Patterns" [03.13.02] 10/13/02 10:51 AM Gama Network Presents: The Case For Game Design Patterns By Bernd Kreimeier Gamasutra March 13, 2002 URL: http://www.gamasutra.com/features/20020313/kreimeier_01.htm Game design, like any other profession, requires a formal means to document, discuss, and plan. Over the past decades, the designer community could refer to a steadily growing body of past computer games for ideas and inspiration. Knowledge was also extracted from the analysis of board games and other classical games, and from the rigorous formal analysis found in mathematical game theory. However, while knowledge about computer games has grown rapidly, little progress has made to document our individual experiences and knowledge - documentation that is mandatory if the game design profession is to advance. Game design needs a shared vocabulary to name the objects and structures we are creating and shaping, and a set of rules to express how these building blocks fit together. This article proposes to adopt a pattern formalism for game design, based on the work of Christopher Alexander. Alexandrian patterns are simple collections of reusable solutions to solve recurring problems. Doug Church's "Formal Abstract Design Tools" [11] or Hal Barwood's "400 Design Rules" [6,7,18] have the same objective: to establish a formal means of describing, sharing and expanding knowledge about game design. From the very first interactive computer games, game designers have worked around this deficiency by relying on techniques and tools borrowed from other, older media -- predominantly tools for describing narrative media like cinematography, scriptwriting and storytelling. -

An Advanced Path Tracing Architecture for Movie Rendering

RenderMan: An Advanced Path Tracing Architecture for Movie Rendering PER CHRISTENSEN, JULIAN FONG, JONATHAN SHADE, WAYNE WOOTEN, BRENDEN SCHUBERT, ANDREW KENSLER, STEPHEN FRIEDMAN, CHARLIE KILPATRICK, CLIFF RAMSHAW, MARC BAN- NISTER, BRENTON RAYNER, JONATHAN BROUILLAT, and MAX LIANI, Pixar Animation Studios Fig. 1. Path-traced images rendered with RenderMan: Dory and Hank from Finding Dory (© 2016 Disney•Pixar). McQueen’s crash in Cars 3 (© 2017 Disney•Pixar). Shere Khan from Disney’s The Jungle Book (© 2016 Disney). A destroyer and the Death Star from Lucasfilm’s Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (© & ™ 2016 Lucasfilm Ltd. All rights reserved. Used under authorization.) Pixar’s RenderMan renderer is used to render all of Pixar’s films, and by many 1 INTRODUCTION film studios to render visual effects for live-action movies. RenderMan started Pixar’s movies and short films are all rendered with RenderMan. as a scanline renderer based on the Reyes algorithm, and was extended over The first computer-generated (CG) animated feature film, Toy Story, the years with ray tracing and several global illumination algorithms. was rendered with an early version of RenderMan in 1995. The most This paper describes the modern version of RenderMan, a new architec- ture for an extensible and programmable path tracer with many features recent Pixar movies – Finding Dory, Cars 3, and Coco – were rendered that are essential to handle the fiercely complex scenes in movie production. using RenderMan’s modern path tracing architecture. The two left Users can write their own materials using a bxdf interface, and their own images in Figure 1 show high-quality rendering of two challenging light transport algorithms using an integrator interface – or they can use the CG movie scenes with many bounces of specular reflections and materials and light transport algorithms provided with RenderMan. -

Alpha and the History of Digital Compositing

Alpha and the History of Digital Compositing Technical Memo 7 Alvy Ray Smith August 15, 1995 Abstract The history of digital image compositing—other than simple digital imple- mentation of known film art—is essentially the history of the alpha channel. Dis- tinctions are drawn between digital printing and digital compositing, between matte creation and matte usage, and between (binary) masking and (subtle) mat- ting. The history of the integral alpha channel and premultiplied alpha ideas are pre- sented and their importance in the development of digital compositing in its cur- rent modern form is made clear. Basic Definitions Digital compositing is often confused with several related technologies. Here we distinguish compositing from printing and matte creation—eg, blue-screen matting. Printing v Compositing Digital film printing is the transfer, under digital computer control, of an im- age stored in digital form to standard chemical, analog movie film. It requires a sophisticated understanding of film characteristics, light source characteristics, precision film movements, film sizes, filter characteristics, precision scanning de- vices, and digital computer control. We had to solve all these for the Lucasfilm laser-based digital film printer—that happened to be a digital film input scanner too. My colleague David DiFrancesco was honored by the Academy of Motion Picture Art and Sciences last year with a technical award for his achievement on the scanning side at Lucasfilm (along with Gary Starkweather). Also honored was Gary Demos for his CRT-based digital film scanner (along with Dan Cam- eron). Digital printing is the generalization of this technology to other media, such as video and paper. -

MONSTERS INC 3D Press Kit

©2012 Disney/Pixar. All Rights Reserved. CAST Sullivan . JOHN GOODMAN Mike . BILLY CRYSTAL Boo . MARY GIBBS Randall . STEVE BUSCEMI DISNEY Waternoose . JAMES COBURN Presents Celia . JENNIFER TILLY Roz . BOB PETERSON A Yeti . JOHN RATZENBERGER PIXAR ANIMATION STUDIOS Fungus . FRANK OZ Film Needleman & Smitty . DANIEL GERSON Floor Manager . STEVE SUSSKIND Flint . BONNIE HUNT Bile . JEFF PIDGEON George . SAM BLACK Additional Story Material by . .. BOB PETERSON DAVID SILVERMAN JOE RANFT STORY Story Manager . MARCIA GWENDOLYN JONES Directed by . PETE DOCTER Development Story Supervisor . JILL CULTON Co-Directed by . LEE UNKRICH Story Artists DAVID SILVERMAN MAX BRACE JIM CAPOBIANCO Produced by . DARLA K . ANDERSON DAVID FULP ROB GIBBS Executive Producers . JOHN LASSETER JASON KATZ BUD LUCKEY ANDREW STANTON MATTHEW LUHN TED MATHOT Associate Producer . .. KORI RAE KEN MITCHRONEY SANJAY PATEL Original Story by . PETE DOCTER JEFF PIDGEON JOE RANFT JILL CULTON BOB SCOTT DAVID SKELLY JEFF PIDGEON NATHAN STANTON RALPH EGGLESTON Additional Storyboarding Screenplay by . ANDREW STANTON GEEFWEE BOEDOE JOSEPH “ROCKET” EKERS DANIEL GERSON JORGEN KLUBIEN ANGUS MACLANE Music by . RANDY NEWMAN RICKY VEGA NIERVA FLOYD NORMAN Story Supervisor . BOB PETERSON JAN PINKAVA Film Editor . JIM STEWART Additional Screenplay Material by . ROBERT BAIRD Supervising Technical Director . THOMAS PORTER RHETT REESE Production Designers . HARLEY JESSUP JONATHAN ROBERTS BOB PAULEY Story Consultant . WILL CSAKLOS Art Directors . TIA W . KRATTER Script Coordinators . ESTHER PEARL DOMINIQUE LOUIS SHANNON WOOD Supervising Animators . GLENN MCQUEEN Story Coordinator . ESTHER PEARL RICH QUADE Story Production Assistants . ADRIAN OCHOA Lighting Supervisor . JEAN-CLAUDE J . KALACHE SABINE MAGDELENA KOCH Layout Supervisor . EWAN JOHNSON TOMOKO FERGUSON Shading Supervisor . RICK SAYRE Modeling Supervisor . EBEN OSTBY ART Set Dressing Supervisor . -

BOCQUET Gavin

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd GAVIN BOCQUET - Production Designer WOOL Director: Morten Tyldum Producers: Morten Tyldum, Graham Yost, Rebecca Ferguson & Hugh Howey Starring: Rebecca Ferguson and Tim Robbins AMC Studios JINGLE JANGLE Director: David E. Talbert Producers: Vicki Dee Rock, David E. Talbert, Mike Jackson, John Legend and Lyn Talbert Starring: Forest Whitaker, Keegan-Michael Key and Anika Noni Rose 260 Degrees Entertainment / Netflix THE DARK CRYSTAL: AGE OF RESISTANCE Director: Louis Leterrier Producer: Ritamarie Peruggi Starring: Taron Egerton, Anna Taylor Joy, Nathalie Emmanuel, Mark Hamill, and Simon Pegg The Jim Henson Company / Netflix EMMY Award 2020 – Outstanding ChildrEn’s Programme MUTE Director: Duncan Jones Producer: Stuart Fenegan Starring: Sam Rockwell, Justin Theroux, Paul Rudd and Alexander Skarsgård Liberty Films UK / Netflix British Film DEsignErs Guild Nomination 2018 – Best IndEpEndEnt FeaturE Film (Contemporary) MISS PEREGRINE'S HOME FOR PECULIAR CHILDREN Director: Tim Burton Producer: Peter Chernin Starring: Eva Green, Asa Butterfield, Ella Purnell and Bomber Hurley-Smith Chernin Entertainment / Twentieth Century Fox WARCRAFT: THE BEGINNING Director: Duncan Jones Producers: Alex Gartner, Jon Jashni, Charles Roven and Thomas Tull Starring: Paula Patton, Dominic Cooper, Travis Fimmel, Ben Foster, Clancy Brown and Toby Kebbell Universal Pictures Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 Registered Company No. 032 91044 Registered in England Registered Office: Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP GAVIN BOCQUET Contd … 2 JACK THE GIANT SLAYER Director: Bryan Singer Producers: David Dobkin, Patrick McCormick and Neal H Moritz Starring: Ewan McGregor, Stanley Tucci, Ian McShane, Nicholas Hoult, Bill Nighy and Warwick Davis Warner Bros. -

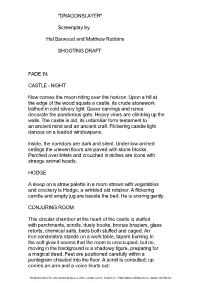

"DRAGONSLAYER" Screenplay by Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins SHOOTING DRAFT FADE IN: CASTLE

"DRAGONSLAYER" Screenplay by Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins SHOOTING DRAFT FADE IN: CASTLE - NIGHT Now comes the moon riding over the horizon. Upon a hill at the edge of the wood squats a castle, its crude stonework bathed in cold silvery light. Queer carvings and runes decorate the ponderous gate. Heavy vines are climbing up the walls. The castle is old, its unfamiliar form testament to an ancient mind and an ancient craft. Flickering candle light dances on a leaded windowpane. Inside, the corridors are dark and silent. Under low arched ceilings the uneven floors are paved with stone blocks. Perched over lintels and crouched in niches are icons with strange animal heads. HODGE A sleep on a straw palette in a room strewn with vegetables and crockery is Hodge, a wrinkled old retainer. A flickering candle and empty jug are beside the bed. He is snoring gently. CONJURING ROOM This circular chamber at the heart of the castle is stuffed with parchments, scrolls, dusty books, bronze braziers, glass retorts, chemical salts, birds both stuffed and caged. An iron candelabra stands on a work table, tapers burning. In the soft glow it seems that the room is unoccupied, but no, moving in the background is a shadowy figure, preparing for a magical deed. Feet are positioned carefully within a pentagram chiseled into the floor. A scroll is consulted; up comes an arm and a voice blurts out: Script provided for educational purposes. More scripts can be found here: http://www.sellingyourscreenplay.com/library VOICE Omnia in duos: Duo in Unum: Unus in Nihil: Haec nec Quattuor nec Omnia nec Duo nec Unus nec Nihil Sunt. -

Downloaded for Storage and Display—As Is Common with Contemporary Systems—Because in 1952 There Were No Image File Formats to Capture the Graphical Output of a Screen

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The random-access image: Memory and the history of the computer screen Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0b3873pn Journal Grey Room, 70(70) ISSN 1526-3819 Author Gaboury, J Publication Date 2018-03-01 DOI 10.1162/GREY_a_00233 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California John Warnock and an IDI graphical display unit, University of Utah, 1968. Courtesy Salt Lake City Deseret News . 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00233 The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen JACOB GABOURY A memory is a means for displacing in time various events which depend upon the same information. —J. Presper Eckert Jr. 1 When we speak of graphics, we think of images. Be it the windowed interface of a personal computer, the tactile swipe of icons across a mobile device, or the surreal effects of computer-enhanced film and video games—all are graphics. Understandably, then, computer graphics are most often understood as the images displayed on a computer screen. This pairing of the image and the screen is so natural that we rarely theorize the screen as a medium itself, one with a heterogeneous history that develops in parallel with other visual and computa - tional forms. 2 What then, of the screen? To be sure, the computer screen follows in the tradition of the visual frame that delimits, contains, and produces the image. 3 It is also the skin of the interface that allows us to engage with, augment, and relate to technical things. -

Hereby the Screen Stands in For, and Thereby Occludes, the Deeper Workings of the Computer Itself

John Warnock and an IDI graphical display unit, University of Utah, 1968. Courtesy Salt Lake City Deseret News . 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00233 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00233 by guest on 27 September 2021 The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen JACOB GABOURY A memory is a means for displacing in time various events which depend upon the same information. —J. Presper Eckert Jr. 1 When we speak of graphics, we think of images. Be it the windowed interface of a personal computer, the tactile swipe of icons across a mobile device, or the surreal effects of computer-enhanced film and video games—all are graphics. Understandably, then, computer graphics are most often understood as the images displayed on a computer screen. This pairing of the image and the screen is so natural that we rarely theorize the screen as a medium itself, one with a heterogeneous history that develops in parallel with other visual and computa - tional forms. 2 What then, of the screen? To be sure, the computer screen follows in the tradition of the visual frame that delimits, contains, and produces the image. 3 It is also the skin of the interface that allows us to engage with, augment, and relate to technical things. 4 But the computer screen was also a cathode ray tube (CRT) phosphorescing in response to an electron beam, modified by a grid of randomly accessible memory that stores, maps, and transforms thousands of bits in real time. The screen is not simply an enduring technique or evocative metaphor; it is a hardware object whose transformations have shaped the ma - terial conditions of our visual culture.