Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea: Exploring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immeuble CCIA, Avenue Jean Paul II, 01 BP 1387, Abidjan 01 Cote D'ivoire

REQUEST FOR EXPRESSIONS OF INTEREST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP Immeuble CCIA, Avenue Jean Paul II, 01 BP 1387, Abidjan 01 Cote d’Ivoire Gender, Women and Civil Society Department (AHGC) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Telephone: +22520264246 Title of the assignment: Consultant-project coordinator to help the Department of Gender, Women and Civil Society (AHGC) in TSF funded project (titled Economic Empowerment of Vulnerable Women in the Sahel Region) in Chad, Mali and Niger. The African Development Bank, with funding from the Transition Support Facility (TSF), hereby invites individual consultants to express their interest for a consultancy to support the Multinational project Economic Empowerment of Vulnerable Women in three transition countries specifically Chad, Mali and Niger Brief description of the Assignment: The consultant-project coordinator will support the effective operationalization of the project that includes: (i) Developing the project’s annual work Plan and budget and coordinating its implementation; (ii) Preparing reports or minutes for various activities of the project at each stage of each consultancy in accordance with the Bank reporting guideline; (iii) Contributing to gender related knowledge products on G5 Sahel countries (including country gender profiles, country policy briefs, etc.) that lead to policy dialogue with a particular emphasis on fragile environments. Department issuing the request: Gender, Women and Civil Society Department (AHGC) Place of assignment: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire Duration of the assignment: 12 months Tentative Date of commencement: 5th September 2020 Deadline for Applications: Wednesday 26th August 2020 at 17h30 GMT Applications to be submitted to: [email protected]; [email protected] ; [email protected] For the attention of: Ms. -

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies Economics Department 2014 History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade Part of the Econometrics Commons, Growth and Development Commons, International Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Kam Kah, Henry, "History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)" (2014). Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies 2014 Volume 3 Issue 1 ISSN:2161-8216 History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon ABSTRACT This paper examines the complex involvement of neighbors and other states in the leadership or political crisis in the CAR through a content analysis. It further discusses the repercussions of this on the unity and leadership of the country. The CAR has, for a long time, been embroiled in a crisis that has impeded the unity of the country. It is a failed state in Africa to say the least, and the involvement of neighboring and other states in the crisis in one way or the other has compounded the multifarious problems of this country. -

Mali – Beyond Cotton, Searching for “Green Gold”* Yoshiko Matsumoto-Izadifar

Mali – Beyond Cotton, Searching for “Green Gold”* Yoshiko Matsumoto-Izadifar Mali is striving for agricultural diversification to lessen its high dependence on cotton and gold. The Office du Niger zone has great potential for agricultural diversification, in particular for increasing rice and horticultural production. Tripartite efforts by private agribusiness, the Malian government and the international aid community are the key to success. Mali’s economy faces the challenge of Office du Niger Zone: Growing Potential for agricultural diversification, as it needs to lessen Agricultural Diversification its excessive dependence on cotton and gold. Livestock, cotton and gold are currently the In contrast to the reduced production of cotton, country’s main sources of export earnings (5, 25 cereals showed good progress in 2007. A and 63 per cent respectively in 2005). However, substantial increase in rice production (up more a decline in cotton and gold production in 2007 than 40 per cent between 2002 and 2007) shows slowed the country’s economic growth. Mali has the potential to overcome its dependence on cotton (FAO, 2008). The Recent estimates suggest that the country’s gold government hopes to make the zone a rice resources will be exhausted in ten years (CCE, granary of West Africa. 2007), and “white gold”, as cotton is known, is in a difficult state owing to stagnant productivity The Office du Niger zone (see Figure 1), one of and low international market prices, even the oldest and largest irrigation schemes in sub- though the international price of cotton Saharan Africa, covers 80 per cent of Mali’s increased slightly in 2007 (AfDB/OECD, 2008). -

Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger

BURKINA FASO, MALI AND NIGER Vulnerability to COVID-19 Containment Measures Thematic report – April 2020 Any questions? Please contact us at [email protected] ACAPS Thematic report: COVID-19 in the Sahel About this report is a ‘bridge’ between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. It is an area of interaction between African indigenous cultures, nomadic cultures, and Arab and Islamic cultures Methodology and overall objective (The Conversation 28/02/2020). ACAPS is focusing on Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger because these three countries This report highlights the potential impact of COVID-19 containment measures in three constitute a sensitive geographical area. The escalation of conflict in Mali in 2015 countries in the Sahel region: Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. It is based on ACAPS’ global exacerbated regional instability as conflict began to spill across the borders. In 2018 ‘Vulnerability to containment measures’ analysis that highlights how eight key factors can regional insecurity increased exponentially as the conflict intensified in both Niger and shape the impact of COVID-19 containment measures. Additional factors relevant to the Burkina Faso. This led to a rapid deterioration of humanitarian conditions (OCHA Sahel region have also been included in this report. The premise of this regional analysis 24/02/2020). Over the past two years armed groups’ activities intensified significantly in the is that, given these key factors, the three countries are particularly vulnerable to COVID- border area shared by the three countries, known as Liptako Gourma. As a result of 19 containment measures. conflict, the provision of essential services including health, education, and sanitation has This risk analysis does not forecast the spread of COVID-19. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Diasporas, Remittances and Africa South of the Sahara

DIASPORAS, REMITTANCES AND AFRICA SOUTH OF THE SAHARA A STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT MARC-ANTOINE PÉROUSE DE MONTCLOS ISS MONOGRAPH SERIES • NO 112, MARCH 2005 CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR iv GLOSSARY AND ABBREVIATIONS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 5 African diasporas and homeland politics CHAPTER 2 27 The political value of remittances: Cape Verde, Comores and Lesotho CHAPTER 3 43 The dark side of diaspora networking: Organised crime and terrorism CONCLUSION 65 iv ABOUT THE AUTHOR Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos is a political scientist with the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD). He works on forced migrations and has published various books on the issue, especially on Somali refugees (Diaspora et terrorisme, 2003). He lived for several years in Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya, and conducted field investigations in the Comores, Cape Verde and Lesotho in 2002 and 2003. This study is the result of long-term research on the subject. v GLOSSARY AND ABBREVIATIONS ANC: African National Congress BCP: Basotho Congress Party BNP: Basotho National Party COSATU: Congress of South African Trade Unions ECOWAS: Economic Community of West African States FRELIMO: Frente de Libertação de Moçambique GDP: Gross Domestic Product GNP: Gross National Product INAME: Instituto Nacional de Apoio ao Emigrante Moçambicano no Exterior IOM: International Organisation for Migration IRA: Irish Republican Army LCD: Lesotho Congress for Democracy LLA: Lesotho Liberation Army LTTE: Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam MASSOB: Movement for the Actualisation -

Sub-Saharian Immigration in France : from Diversity to Integration

Sub-Saharian immigration in France : from diversity to integration. Caroline JUILLARD Université René Descartes-Paris V The great majority of Sub-Saharian African migration comes from West - Africa, more precisely from francophone countries as Senegal, Mali, and into a lesser extent Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania. There are also migrants from other francophone African countries such as : Zaïre (RDC), Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Niger. Migrants consist mostly of workers and students. I shall speak principally of West-African migration for which sociolinguistic sources are not many. My talk will have three main parts. I General characteristics of this migration. A/ Census data First of all, I will discuss census data. The major trend of immigration to France nowadays comes from Sub-Saharian Africa ; it has tripled between 1982 et 1990 and almost doubled according to the last census of 1999 (Cf. Annexes). According to 1999 census, this migrant population counts more or less 400.000 persons. Official data are multiple and differ from one source to the other. Variations are important. Children born in France from immigrant parents do not participate to the immigrant population and, so for, are not included in the migration population recorded by the national census. They are recorded by the national education services. Moreover, there might be more persons without residency permit within the Sub-Saharian migration than within other migrant communities. I 2 mention here well-known case of “les sans-papiers”, people without residency permit, who recently asked for their integration to France. Case of clandestines has to be mentioned too. Data of INSEE1 do not take into account these people. -

Burkina Faso, Mali & Western Niger

BURKINA FASO, MALI & WESTERN NIGER Humanitarian Snapshot As of 15 November 2019 Escalating violence and insecurity have sparked an unprecedented humanitarian crisis in parts of Burkina Faso, Mali and western Niger. Population displacement has sharply risen, as thousands of civilians flee to seek safety from the recurrent violent attacks. The number of internally displaced people has risen to more than 750,000, a ten-fold increase since 2018. The crisis is affecting extremely vulnerable families, compounding the impact of food insecurity, malnutrition and epidemics. Around 1.8 million people are currently food insecure. Armed assailants are directly targeting schools and forcing health centres to close, jeopardising the future of thousands of children and depriving violence-affected communities of critical services. In 2019, 6.1 million people in the affected regions need urgent assistance, including 3.9 million in Mali, 1.5 million in Burkina Faso, and 700,000 people in western Niger. In support of national and local authorities, humanitarian partners are stepping up operations to save lives and alleviate human suffering. Some US$717 million are required to assist 4.7 million people in the three countries. As of October, only 47 per cent of the funds had been received. Beyond immediate humanitarian action, a coordinated approach integrating cross-border dynamics is required to reverse the spread of conflict and bring meaningful improvement in the lives of millions of affected people. INSECURITY HUMANITARIAN SITUATION PER REGION HUMANITARIAN -

The Niger Delta Petroleum System: Niger Delta Province, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea, Africa by Mlchele L W

uses science for a changing world The Niger Delta Petroleum System: Niger Delta Province, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea, Africa by Mlchele L W. Tuttle,1 Ronald R. Charpentier, 1 and Michael E. Brownfleld1 Open-File Report 99-50-H 1999 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY !Denver, Colorado The Niger Delta Petroleum System: Niger Delta Province, Nigeria Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea, Africa by Michele L. W. Tuttle, Ronald R. Charpentier, and Michael E. Brownfield Open-File Report 99-50-H 1999 CONTENTS Forward by the U.S. Geological Survey World Energy Project Chapter A. Tertiary Niger Delta (Akata-Agbada) Petroleum System (No. 719201), Niger Delta Province, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea, Africa by Michele L. W. Tuttle, Michael E. Brownfield, and Ronald R. Charpentier Chapter B. Assessment of Undiscovered Petroleum in the Tertiary Niger Delta (Akata-Agbada) Petroleum System (No. 719201), Niger Delta Province, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea, Africa by Michele L. W. Tuttle, Ronald R. Charpentier, and Michael E. Brownfield Chapters A and B are issued as a single volume and are not available separately. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Forward, by the U.S. Geological Survey World Energy Project ............................. 1 Chapter A. Tertiary Niger Delta (Akata-Agbada) Petroleum System (No. 719201), Niger Delta Province, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea, Africa by Michele L. -

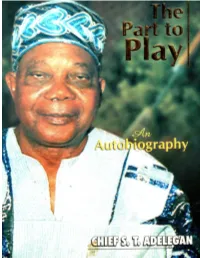

THE PART to PLAY an Autobiography

THE PART TO PLAY An Autobiography of Chief S. T. Adelegan Deputy-Speaker Western Region of Nigeria House of Assembly 1960-1965 The Story of the Life of a Nigerian Humanist, Patriot & Selfless Service i THE PART TO PLAY Author Shadrach Titus Adelegan Printing and Packaging Kingsmann Graffix Copyright: Terrific Investment & Consulting All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Author. Republished 2019 by: Terrific Investment & Consulting ISBN 30455-1-5 All enquiries to: [email protected], [email protected], ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Dedication iv Foreword v Introduction vi Chapter One: ANTECEDENTS 1 Chapter Two: MY EARLY YEARS 31 Chapter Three: AT ST ANDREWS COLLEGE, OYO 45 Chapter Four THE UNFORGETABLE ENCOUNTER WITH OONI ADESOJI ADEREMI 62 Chapter Five DOUBLE PROMOTION AT THE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, IBADAN 73 Chapter Six NOW A GRADUATE TEACHER 86 Chapter Seven THE PRESSURE BY MY NATIVE COMMUNITY & MY DILEMMA 97 Chapter Eight THE COST OF PATRIOTISM & POLITICAL PERSECUTION 111 Chapter Nine: HOW WE BROKE THE MONOPOLY OF DR. NNAMDI AZIKIWE’S NCNC 136 Chapter Ten THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF THE FIRST REPUBLIC 156 Chapter Eleven THE FINAL COLLAPSE OF THE FIRST REPUBLIC - 180 Chapter Twelve COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION MEETING 196 Chapter Thirteen POLITICAL RELATIONSHIP 209 Chapter Fourteen SERVICE WITHOUT REMUNERATION 229 Chapter Fifteen TRIBUTES 250 Chapter Sixteen GOING FORWARD 275 Chapter Seventeen ABOUT THE AUTHOR 280 iii DEDICATION To God Almighty who has used me as an ass To be ridden for His Glory To manifest in the lives of people; And Also, To Humanity iv FOREWORD Shadrach Titus Adelegan, one of Nigeria’s astute politicians of the First Republic, and an outstanding educationist and community leader is one of the few Nigerians who have contributed in great and concrete terms to the development of humanity. -

Nigeria's Southern Africa Policy 1960-1988

CURRENT AFRICAN ISSUES 8 ISSN 0280-2171 PATRICK WILMOT NIGERIA'S SOUTHERN AFRICA POLICY 1960-1988 The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies AUGUST 1989 P.O Box 1703, 5-751 47 UPPSALA Sweden Telex 8195077, Telefax 018-69 5629 2 vi. Regimes tend to conduct public, official policy through the foreign ministry, and informal policy through personal envoys and secret emis saries. vii. Nigeria is one of only about five member states that pays its dues promptly and regularly to the OAV and its Liberation Committee, regard less of the complexion of the regime. viii. In most cases opposition to apartheid is based on sentiment (human ism, universalism, race consciousness) not on objective factors such as the nature of the economic system (part of western imperialism) and the military threat posed by the racist armed forces. 2. Abubakar Tafawa Balewa 1960-1966 Alhaji Sir Abubakar Tafewa Balewa was Prime Minister between October 1960 and January 1966. But he was subordinate to Sir Ahmadu Bello, Sardauna of Sokoto, Premier of the Northern Region and party leader of Tafawa Balewa's Northern People's Congress. The Sardauna's prime in terest was in the Moslem World of North Africa and the Middle East so that Southern Africa was not a priority area. In general policy was determined by the government's pro-Western stand. The foreign minister, Jaja Wachuck wu, was an early advocate of dialogue with South Africa. South Africa was invited to attend Nigeria's Independence celebrations. In the end it did not, due to pressure from Kwame Nkrumah and other progressive African leaders.