A Practical Guide to GPL Compliance 1 Executive Summary 2 Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free and Open Source Software Is Not a “Free for All”: German Court Enforces GPL License Terms

Free and Open Source Software Is Not A “Free For All”: German Court Enforces GPL License Terms The GNU General Public License, computer programs, and to guarantee version 2 (GPLv2) scores another the same rights to the recipients of court victory for the free and/or open works licensed under the GPLv2. source software (FOSS) community. Although the open-source movement The GPLv2 carries important has been active for nearly two conditions, however, most notably— decades, globally there are only and critical for its viability—that any a handful of cases in which a FOSS distribution of software licensed under license has been reviewed by — let the GPLv2 must be accompanied with alone receive the imprimatur of the “complete corresponding machine- enforceability from — a court. The readable source code” or “a written latest case hails from Germany and offer … to give any third party … a serves to underscore the importance complete machine-readable copy of of proper FOSS-license compliance the corresponding source code”. throughout the software development GPLv2, Sections 3(a) and 3(b). process and supply chain, including During a “Hacking for Compliance the obligation of distributors to Workshop” organized in Berlin in 2012 independently verify FOSS-license by the Free Software Foundation compliance representations from their Europe, the source code package for a suppliers. media player with GNU/Linux-based Welte v. Fantec firmware inside was found not to contain the source code for the Harald Welte, founder of gpl- iptables components. It was also violations.org (a non-profit discovered that the source code for organization aiming at the other device components was not the enforcement of GPL license terms), is same version used to compile the the owner of “netfilter/iptables” firmware’s binary code. -

Open Source Software Notice

OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE NOTICE DCS Touch Display Software V2.00.XXX Schüco International KG Karolinenstraße 1-15 33609 Bielefeld OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE NOTICE Seite 1 von 32 10000507685_02_EN OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE NOTICE This document contains information about open source software for this product. The rights granted under open source software licenses are granted by the respective right holders. In the event of conflicts between SCHÜCO’S license conditions and the applicable open source licenses, the open source license conditions take precedence over SCHÜCO’S license conditions with regard to the respective open source software. You are allowed to modify SCHÜCO’S proprietary programs and to conduct reverse engineering for the purpose of debugging such modifications, to the extent such programs are linked to libraries licensed under the GNU Lesser General Public License. You are not allowed to distribute information resulting from such reverse engineering or to distribute the modified proprietary programs. The rightholders of the open source software require to refer to the following disclaimer, which shall apply with regard to those rightholders: Warranty Disclaimer THE OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE IN THIS PRODUCT IS DISTRIBUTED ON AN "AS IS" BASIS AND IN THE HOPE THAT IT WILL BE USEFUL, BUT WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, WITHOUT EVEN THE IMPLIED WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. SEE THE APPLICABLE LICENSES FOR MORE DETAILS. OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE NOTICE Seite 2 von 32 10000507685_02_EN Copyright Notices and License Texts (please see the source code for all details) Software: iptables Copyright notice: Copyright (C) 1989, 1991 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Copyright Google, Inc. -

Netfilter's Connection Tracking System

FILTERING POLICIES BASED UNIQUELY on packet header information are obsolete. PABLO NEIRA AYUSO These days, stateful firewalls provide advanced mechanisms to let sysadmins Netfilter’s and security experts define more intelli- gent policies. This article describes the connection implementation details of the connection tracking system tracking system provided by the Netfilter project and also presents the required Pablo Neira Ayuso has an M.S. in computer science background to understand it, such as an and has worked for several companies in the IT secu- rity industry, with a focus on open source solutions. understanding of the Netfilter framework. Nowadays he is a full-time teacher and researcher at the University of Seville. This article will be the perfect complement to understanding the subsystem that [email protected] enables the stateful firewall available in any recent Linux kernel. The Netfilter Framework The Netfilter project was founded by Paul “Rusty” Russell during the 2.3.x development series. At that time the existing firewalling tool for Linux had serious drawbacks that required a full rewrite. Rusty decided to start from scratch and create the Netfilter framework, which comprises a set of hooks over the Linux network protocol stack. With the hooks, you can register kernel modules that do some kind of network packet handling at different stages. Iptables, the popular firewalling tool for Linux, is commonly confused with the Netfilter framework itself. This is because iptables chains and hooks have the same names. But iptables is just a brick on top of the Netfilter framework. Fortunately, Rusty spent considerable time writ- ing documentation [1] that comes in handy for anyone willing to understand the framework, al- though at some point you will surely feel the need to get your hands dirty and look at the code to go further. -

Step-By-Step Strategies and Case Studies for Embedded Software Companies to Adapt to the FOSS Ecosystem Suhyun Kim, Jaehyun Yoo, Myunghwa Lee

Step-by-Step Strategies and Case Studies for Embedded Software Companies to Adapt to the FOSS Ecosystem Suhyun Kim, Jaehyun Yoo, Myunghwa Lee To cite this version: Suhyun Kim, Jaehyun Yoo, Myunghwa Lee. Step-by-Step Strategies and Case Studies for Embed- ded Software Companies to Adapt to the FOSS Ecosystem. 8th International Conference on Open Source Systems (OSS), Sep 2012, Hammamet, Tunisia. pp.48-60, 10.1007/978-3-642-33442-9_4. hal-01519083 HAL Id: hal-01519083 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01519083 Submitted on 5 May 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Step-by-Step Strategies and Case Studies for Embedded Software Companies to Adapt to the FOSS Ecosystem Suhyun Kim, Jaehyun Yoo, and Myunghwa Lee Software Engineering Lab, Software R&D Center, Samsung Electronics 416 Maetan-Dong, Yeongtong-Gu, Suwon, Gyeonggi-Do 443-742, Korea {suhyun47.kim, sjh.yoo, mhlee}@samsung.com WWW home page: https://opensource.samsung.com Abstract Due to the continuous expansion of the FOSS ecosystem and the introduction of high-quality FOSS, FOSS is increasingly used in consumer electronics (CE) such as smartphones, televisions, and cameras. -

Op E N So U R C E Yea R B O O K 2 0

OPEN SOURCE YEARBOOK 2016 ..... ........ .... ... .. .... .. .. ... .. OPENSOURCE.COM Opensource.com publishes stories about creating, adopting, and sharing open source solutions. Visit Opensource.com to learn more about how the open source way is improving technologies, education, business, government, health, law, entertainment, humanitarian efforts, and more. Submit a story idea: https://opensource.com/story Email us: [email protected] Chat with us in Freenode IRC: #opensource.com . OPEN SOURCE YEARBOOK 2016 . OPENSOURCE.COM 3 ...... ........ .. .. .. ... .... AUTOGRAPHS . ... .. .... .. .. ... .. ........ ...... ........ .. .. .. ... .... AUTOGRAPHS . ... .. .... .. .. ... .. ........ OPENSOURCE.COM...... ........ .. .. .. ... .... ........ WRITE FOR US ..... .. .. .. ... .... 7 big reasons to contribute to Opensource.com: Career benefits: “I probably would not have gotten my most recent job if it had not been for my articles on 1 Opensource.com.” Raise awareness: “The platform and publicity that is available through Opensource.com is extremely 2 valuable.” Grow your network: “I met a lot of interesting people after that, boosted my blog stats immediately, and 3 even got some business offers!” Contribute back to open source communities: “Writing for Opensource.com has allowed me to give 4 back to a community of users and developers from whom I have truly benefited for many years.” Receive free, professional editing services: “The team helps me, through feedback, on improving my 5 writing skills.” We’re loveable: “I love the Opensource.com team. I have known some of them for years and they are 6 good people.” 7 Writing for us is easy: “I couldn't have been more pleased with my writing experience.” Email us to learn more or to share your feedback about writing for us: https://opensource.com/story Visit our Participate page to more about joining in the Opensource.com community: https://opensource.com/participate Find our editorial team, moderators, authors, and readers on Freenode IRC at #opensource.com: https://opensource.com/irc . -

Information on Open Source Software When Filling in The

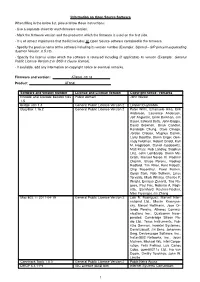

Information on Open Source Software When filling in the below list, please follow these instructions: - Use a separate sheet for each firmware version. - Mark the firmware version and the product in which the firmware is used on the first side. - It is of utmost importance that the list includes all Open Source software contained in the firmware. - Specify the precise name of the software including its version number (Example: Siproxd – SIP proxy/masquerading daemon Version: 0.5.10). - Specify the license under which the software is released including (if applicable) its version (Example: General Public License Version 2 or BSD-3 clause license). - If available, add any information on copyright notice or eventual remarks. Firmware and version: AT904L-03.18 Product: AT904L Software and version number License and License Version Copyright notice / remarks Encode and Decode base64 files Public domain John Walker 1.5 bridge-utils 1.4 General Public License Version 2 Lennert Buytenhek BusyBox 1.16.2 General Public License Version 2 Peter Willis, Emanuele Aina, Erik Andersen, Laurence Anderson, Jeff Angielski, Enrik Berkhan, Jim Bauer, Edward Betts, John Beppu, David Brownell, Brian Candler, Randolph Chung, Dave Cinege, Jordan Crouse, Magnus Damm, Larry Doolittle, Glenn Engel, Gen- nady Feldman, Robert Griebl, Karl M. Hegbloom, Daniel Jacobowitz, Matt Kraai, Rob Landley, Stephan Linz, John Lombardo, Glenn Mc- Grath, Manuel Novoa III, Vladimir Oleynik, Bruce Perens, Rodney Radford, Tim Riker, Kent Robotti, Chip Rosenthal, Pavel Roskin, Gyepi Sam, Rob Sullivan, Linus Torvalds, Mark Whitley, Charles P. Wright, Enrique Zanardi, Tito Ra- gusa, Paul Fox, Roberto A. Fogli- etta, Bernhard Reutner-Fischer, Mike Frysinger, Jie Zhang Mac 802.11 2011-04-19 General Public License Version 2 Luis R. -

Licensing Information User Manual Oracle® ILOM

Licensing Information User Manual ® Oracle ILOM Firmware Release 3.2.x October 2018 Part No: E62005-12 October 2018 Licensing Information User Manual Oracle ILOM Firmware Release 3.2.x Part No: E62005-12 Copyright © 2016, 2018, Oracle and/or its affiliates. License Restrictions Warranty/Consequential Damages Disclaimer This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. Warranty Disclaimer The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. Restricted Rights Notice If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs (including any operating system, integrated software, any programs embedded, installed or activated on delivered hardware, and modifications of such programs) and Oracle computer documentation or other Oracle data delivered to or accessed by U.S. Government -

The Future of Linux Packet Filtering

The future of Linux packet filtering by Harald Welte <[email protected]> Future of Linux packet filtering Contents Problems with current 2.4/2.5 netfilter/iptables Solution to code replication Solution for dynamic rulesets Solution for API to GUI's and other management programs Other current work Optimizing Rule load time of large rulesets Making netfilter/iptables compatible with zerocopy tcp HA for stateful firewalling What's special about firewalling HA Poor man's failover Real state replication Future of Linux packet filtering Problems with 2.4.x netfilter/iptables code replication between iptables/ip6tables/arptables iptables was never meant for other protocols, but people did copy+paste 'ports' replication of core kernel code layer 3 independent matches (mac, interface, ...) userspace library (libiptc) userspace tool (iptables) userspace plugins (libipt_xxx.so) doesn't suit the needs for dynamically changing rulesets dynamic rulesets becomming more common due (service selection, IDS) a whole table is created in userspace and sent as blob to kernel for every ruleset the table needs to be copied to userspace and back inside kernel consistency checks on whole table, loop detection too extensible for writing any forward-compatible GUI new extensions showing up all the time a frontend would need to know about the options and use of a new extension thus frontends are always incomplete and out-of-date no high-level API other than piping to iptables-restore Future of Linux packet filtering Reducing code replication code replication is -

Running FOSS Cellular Networks on Linux

Proceedings of NetDev 1.1: The Technical Conference on Linux Networking (February 10th-12th 2016. Seville, Spain) Running FOSS Cellular Networks on Linux Harald Welte <[email protected]> Proceedings of NetDev 1.1: The Technical Conference on Linux Networking (February 10th-12th 2016. Seville, Spain) What this talk is about Implementing GSM/GPRS network elements as FOSS Applied Protocol Archeology Doing all of that on top of Linux (in userspace) If you expeccted kernel stuff, you’ll be disappointed Proceedings of NetDev 1.1: The Technical Conference on Linux Networking (February 10th-12th 2016. Seville, Spain) Running your own Internetstyle network use offtheshelf hardware (x86, Ethernet card) use any random Linux distribution configure Linux kernel TCP/IP network stack enjoy fancy features like netfilter/iproute2/tc use apache/lighttpd/nginx on the server use Firefox/chromium/konqueor/lynx on the client do whatever modification/optimization on any part of the stack Proceedings of NetDev 1.1: The Technical Conference on Linux Networking (February 10th-12th 2016. Seville, Spain) Running your own GSM network Until 2009 the situation looked like this: go to Ericsson/Huawei/ZTE/Nokia/Alcatel/… spend lots of time convincing them that you’re an eligible customer spend a sixdigit figure for even the most basic full network end up with black boxes you can neither study nor improve WTF? I’ve grown up with FOSS and the Internet. I know a better world. Proceedings of NetDev 1.1: The Technical Conference on Linux Networking (February 10th-12th 2016. Seville, Spain) Why no cellular FOSS? both cellular (2G/3G/4G) and TCP/IP/HTTP protocol specs are publicly available for decades. -

Free Software for GSM Cellular Telephony Openbsc, Osmobts, Osmosgsn, Openggsn

Researching GSM/3G security OpenBSC Free Software for GSM cellular telephony OpenBSC, OsmoBTS, OsmoSGSN, OpenGGSN Harald Welte gnumonks.org osmocom.org sysmocom.de DORS/CLUC, June 2014, Zagreb Harald Welte Free Software for GSM cellular telephony Researching GSM/3G security OpenBSC Outline 1 Researching GSM/3G security 2 OpenBSC Harald Welte Free Software for GSM cellular telephony Researching GSM/3G security OpenBSC About the speaker Using + playing with GNU/Linux since 1994 Kernel / bootloader / driver / firmware development since 1999 IT security expert, focus on network protocol security Core developer of Linux packet filter netfilter/iptables Trained as Electrical Engineer Always looking for interesting protocols (RFID, DECT, GSM) Harald Welte Free Software for GSM cellular telephony Researching GSM/3G security OpenBSC Success of Free Software depending on area of computing Free Software has proven to be successful in many areas of computing Operating Systems (GNU/Linux) Internet Servers (Apache, Sendmail, Exim, Cyrus, ...) Desktop Computers (gnome, KDE, Firefox, LibreOffice, ...) Mobile Devices Embedded network devices (Router, Firewall, NAT, WiFi-AP) There are more areas to computing that people tend to forget. Examples in the communications area: Cellular telephony networks (GSM, 3G, LTE) Professional Mobile Radio (TETRA, TETRAPOL) Cordless telephones (DECT) Harald Welte Free Software for GSM cellular telephony The closed GSM industry Researching GSM/3G security Security implications OpenBSC The GSM network The GSM protocols Free -

Openbsc Network-Side GSM Stack Running on Top of Linux

GSM/3G security OpenBSC: Implementing GSM protocols Security analysis Summary OpenBSC network-side GSM stack running on top of Linux Harald Welte <[email protected]> gnumonks.org gpl-violations.org OpenBSC airprobe.org hmw-consulting.de Linux Kongress 2009, October 2009, Dresden/Germany Harald Welte <[email protected]> OpenBSC network-side GSM stack GSM/3G security OpenBSC: Implementing GSM protocols Security analysis Summary Outline 1 GSM/3G security The closed GSM industry Security implications The GSM network The GSM protocols 2 OpenBSC: Implementing GSM protocols Getting started OpenBSC software architecture Code Reuse 3 Security analysis Theory The Baseband Observations 4 Summary What we’ve learned WhereHarald Welte we <[email protected]> go from here OpenBSC network-side GSM stack Future Plans Further Reading GSM/3G security OpenBSC: Implementing GSM protocols Security analysis Summary About the speaker Always been fascinated by networking and communications Using + playing with Linux since 1994 Kernel / bootloader / driver / firmware development since 1999 IT security specialist, focus on network protocol security Board-level Electrical Engineering Always looking for interesting protocols (RFID, DECT, GSM) Harald Welte <[email protected]> OpenBSC network-side GSM stack GSM/3G security The closed GSM industry OpenBSC: Implementing GSM protocols Security implications Security analysis The GSM network Summary The GSM protocols GSM/3G protocol security Observation Both GSM/3G and TCP/IP protocol specs are publicly available -

Enforcement of the GNU GPL in Germany and Europe by Till Jaeger Dr

Enforcement of the GNU GPL in Germany and Europe by Till Jaeger Dr. iur., Partner at JBB Rechtsanwälte, Berlin; Co-founder of the Institute for Legal Questions on Free and Open Source Software (ifrOSS); Representative of gpl-violations.org project in its enforcement activities. Abstract: GPL enforcement is successful in Europe. In several court decisions and out of court settlements the license conditions of the GPL have been successfully enforced. In particular, embedded systems are the main focus of such compliance activities. The article describes the practice of enforcement activities and the legal prerequisites under the application of German law. Keywords: Free Software, Open Source Software, GNU GPL, enforcement, out of court proceedings, license violation, damages © 2010 Till Jaeger Any party may modify and pass on this article as physical copies and by electronic means and make it available for download under the terms and conditions of the Free Digital Peer Publishing Licence (f-DPPL). The text of the licence may be accessed and retrieved via Internet at http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0009-fdppl-v3-en3. As an alternative, this article may also be used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License, available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0. Recommended citation: Jaeger, Till, Enforcement of the GNU GPL in Germany and Europe, 1 (2010) JIPITEC 34, para. 1. A. Rationale for enforce- 2 After the first enforcement cases became public, ment of the GPL more and more interested parties informed Mr. Welte about other violations. He then decided to establish ‘www.gpl-violations.org’ to provide 1 At present, the enforcement of the GPL license a platform for enforcement activities and public conditions is driven by single developers and documentation of his and others’ efforts to bring organizations supporting Free Software.