Asia Report 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 51.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, February 09, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Rajapaksa, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Minister of Buddhasasana, Religious & Cultural Affairs and Minister of Urban Development & Housing Hon. Rohitha Abegunawardhana, Minister of Ports & Shipping Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. (Prof.) G. L. Peiris, Minister of Education Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Keheliya Rambukwella, Minister of Mass Media Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security, Home Affairs and Disaster Management ( 2 ) M. No. 51 Hon. Namal Rajapaksa, Minister of Youth & Sports Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection Hon. -

The Sri Lankan Insurgency: a Rebalancing of the Orthodox Position

THE SRI LANKAN INSURGENCY: A REBALANCING OF THE ORTHODOX POSITION A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Peter Stafford Roberts Department of Politics and History, Brunel University April 2016 Abstract The insurgency in Sri Lanka between the early 1980s and 2009 is the topic of this study, one that is of great interest to scholars studying war in the modern era. It is an example of a revolutionary war in which the total defeat of the insurgents was a decisive conclusion, achieved without allowing them any form of political access to governance over the disputed territory after the conflict. Current literature on the conflict examines it from a single (government) viewpoint – deriving false conclusions as a result. This research integrates exciting new evidence from the Tamil (insurgent) side and as such is the first balanced, comprehensive account of the conflict. The resultant history allows readers to re- frame the key variables that determined the outcome, concluding that the leadership and decision-making dynamic within the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) had far greater impact than has previously been allowed for. The new evidence takes the form of interviews with participants from both sides of the conflict, Sri Lankan military documentation, foreign intelligence assessments and diplomatic communiqués between governments, referencing these against the current literature on counter-insurgency, notably the social-institutional study of insurgencies by Paul Staniland. It concludes that orthodox views of the conflict need to be reshaped into a new methodology that focuses on leadership performance and away from a timeline based on periods of major combat. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 59.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, March 10, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Rajapaksa, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Minister of Buddhasasana, Religious & Cultural Affairs and Minister of Urban Development & Housing Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. (Prof.) G. L. Peiris, Minister of Education Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. Keheliya Rambukwella, Minister of Mass Media Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi, Minister of Health Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation ( 2 ) M. No. 59 Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament for 23.01.2020

(Eighth Parliament - Fourth Session ) No . 7. ]]] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, January 23, 2020 at 10.30 a.m. PRESENT ::: Hon. J. M. Ananda Kumarasiri, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Transport Service Management and Minister of Power & Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign Relations and Minister of Skills Development, Employment and Labour Relations and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Environment and Wildlife Resources and Minister of Lands & Land Development Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Industries and Export Agriculture Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Roads and Highways and Minister of Ports & Shipping and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Industrial Export and Investment Promotion and Minister of Tourism and Civil Aviation Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena, State Minister of Irrigation and Rural Development Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Public Management and Accounting Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, State Minister of Power Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, State Minister of Youth Affairs Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, State Minister of Lands and Land Development Hon. Wimalaweera Dissanayaka, State Minister of Wildlife Resources Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, State Minister of Water Supply Facilities Hon. Susantha Punchinilame, State Minister of Small & Medium Enterprise Development Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, State Minister of International Co -operation Hon. Tharaka Balasuriya, State Minister of Social Security Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, State Minister of Railway Services Hon. Nimal Lanza, State Minister of Community Development ( 2 ) M. No. 7 Hon. Gamini Lokuge, State Minister of Urban Development Hon. Janaka Wakkumbura, State Minister of Export Agriculture Hon. Vidura Wickramanayaka, State Minister of Agriculture Hon. -

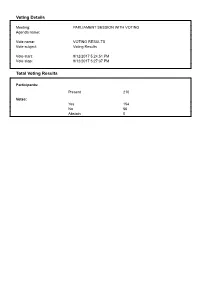

Voting Details Total Voting Results

Voting Details Meeting: PARLIAMENT SESSION WITH VOTING Agenda name: Vote name: VOTING RESULTS Vote subject: Voting Results Vote start: 9/12/2017 5:24:51 PM Vote stop: 9/12/2017 5:27:37 PM Total Voting Results Participants: Present 210 Votes: Yes 154 No 56 Abstain 0 Individual Voting Results GOVERNMENT SIDE G 001. Mangala Samaraweera Yes G 002. S.B. Dissanayake Yes G 003. Nimal Siripala de Silva Yes G 004. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera Yes G 005. John Amaratunga Yes G 006. Lakshman Kiriella Yes G 007. Ranil Wickremesinghe Yes G 009. Gayantha Karunatileka Yes G 010. W.D.J. Senewiratne Yes G 011. Sarath Amunugama Yes G 012. Rauff Hakeem Yes G 013. Rajitha Senaratne Yes G 014. Rishad Bathiudeen Yes G 015. Kabir Hashim Yes G 016. Sajith Premadasa Yes G 017. Malik Samarawickrama Yes G 018. Mano Ganesan Yes G 019. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa Yes G 020. Ven. Athuraliye Rathana Thero Yes G 021. Thilanga Sumathipala Yes G 022. A.D. Susil Premajayantha Yes G 023.Tilak Marapana Yes G 024. Mahinda Samarasinghe Yes G 025. Wajira Abeywardana Yes G 026. S.B. Nawinne Yes G 028. Patali Champika Ranawaka Yes G 029. Mahinda Amaraweera Yes G 030. Navin Dissanayake Yes G 031. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya Yes G 032. Duminda Dissanayake Yes G 033. Wijith Wijayamuni Zoysa Yes G 034. P. Harrison Yes G 035. R.M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara Yes G 036. Arjuna Ranatunga Yes G 037. Palany Thigambaram Yes G 038. Chandrani Bandara Yes G 039. Thalatha Atukorale Yes G 040. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam Yes G 041. -

The Involvement of External Powers in the Post-War Period of the Sri Lankan Ethnic Conflict (2009-2012)

THE INVOLVEMENT OF EXTERNAL POWERS IN THE POST-WAR PERIOD OF THE SRI LANKAN ETHNIC CONFLICT (2009-2012) Meenadchisundram Sivapalan (Researcher) Dr. Alain Tschudin (Supervisor) Submitted in partial-fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Social Science Conflict Transformation and Peace Studies School of Social Science University of KwaZulu-Natal (Howard College) November 2012 CONTENTS Table of Contents i Figures ii Abstract iii Acknowledgement iv Declaration v Abbreviation vi Chapter One: Introduction 1.1. Overview & Significance of the Study 01 1.2. Literature Review 06 1.3. Theoretical Framework 10 1.4. Research Methodology 12 Chapter Two: The Sri Lankan Ethnic Conflict 2.1. Historical Background of the Ethnic Conflict 14 Chapter Three: An Audit of the Sri Lankan Peace Process 3.1. The Norwegian Facilitated Peace Talks 25 Chapter Four: Eelam War-IV 4.1. From Shadow War to Full-Scale War 36 Chapter Five: Post-War Sri Lanka 5.1. The Present Situation in Sri Lanka 44 Chapter Six: Conclusion & Recommendations 6.1. Prospects of Peace 54 6.2. References 64 i FIGURES 1. Map of Sri Lanka 01 2. String of Pearls and Chinese Oil Supply Route 02 3. India-Sri Lanka Map 14 4. Provincial Map of Sri Lanka 15 5. Shrinking LTTE Territories 36 ii ABSTRACT This essay specifically focuses on how the conflicting and competing interests of regional and extra-regional powers shape or affect the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka. It offers a nuanced understanding of the contemporary Sri Lankan ethnic conflict in the context of external engagement. Looking at the historical background of the conflict, and cognizant of neo- realist and democratic peace theories, it explains why the Sri Lankan ethnic conflict still defies solution. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 60.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, March 23, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. (Prof.) G. L. Peiris, Minister of Education Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. Keheliya Rambukwella, Minister of Mass Media Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Namal Rajapaksa, Minister of Youth & Sports Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi, Minister of Health Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries ( 2 ) M. No. 60 Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. Dilum Amunugama, State Minister of Vehicle Regulation, Bus Transport Services and Train Compartments and Motor Car Industry Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection Hon. -

Parliamentary Series First Report

Parliamentary Series No. 11 of THE SIXTH PARLIAMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA (Fourth Session) First Report From The Committee on Public Enterprises Presented by Hon. W D J Senewiratne Chairman of the Committee on 19 August 2009 i MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC ENTERPRISES for the Fourth Session of the Sixth Parliament 1. Hon. W. D. J. Seneviratne (Chairman) 2. Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithra Devi Wanniarachchi 3. Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha 4. Hon. Hemakumara Nanayakkara 5. Hon. Lakshman Yapa Abeywardena 6. Hon. Chandrasiri Gajadeera 7. Hon. A. P. Jagath Pushpakumara 8. Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera 9. Hon. (Dr.) Mervyn Silva 10. Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage 11. Hon. Navin Dissanayake 12. Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna 13. Hon. Piyasiri Wijenayake 14. Hon. Muthu Sivalingam 15. Hon. Hussain Ahamed Bhaila 16. Hon. (Mrs.) Renuka Herath 17. Hon. John Amaratunga 18. Hon. Mangala Samaraweera 19. Hon. Lakshman Kiriella 20. Hon. Ravi Karunanayake 21. Hon. Anura Dissanayake 22. Hon. K. D. Lalkantha 23. Hon. (Dr.) Jayalath Jayawardana 24. Hon. Kabir Hashim 25. Hon. Bimal Ratnayake 26. Hon. Sunil Handunnetti 27. Hon. Faizal Cassim 28. Hon. M. T. Hassan Ali 29. Hon. Mavai S. Senathirajah 30. Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara 31. Hon. Senathirajah Jeyanandamoorthy 32. Hon. (Ven.) Athuraliye Rathana Thero 33. Hon. Basil Rohana Rajapaksa - ii - MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC ENTERPRISES for the Third Session of the Sixth Parliament 1. Hon. W.D.J. Senewiratne (appointed as Chairman on 23.07.2008) 2. Hon. (Mrs.) Pavitra Devi Wanniarachchi (appointed on 17.03.2009) 3. Hon. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa (resigned on 12.09.2008) 4. -

Minutes of Parliament for 08.01.2020

(Eighth Parliament - Fourth Session) No. 3.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, January 08, 2020 at 1.00 p.m. PRESENT : Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Education and Minister of Sports & Youth Affairs Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign Relations and Minister of Skills Development, Employment and Labour Relations and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Environment and Wildlife Resources and Minister of Lands & Land Development Hon. Janaka Bandara Tennakoon, Minister of Public Administration, Home Affairs, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Douglas Devananda, Minister of Fisheries & Aquatic Resources Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Industries and Export Agriculture Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Roads and Highways and Minister of Ports & Shipping and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Industrial Export and Investment Promotion and Minister of Tourism and Civil Aviation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Mahaweli, Agriculture, Irrigation and Rural Development and Minister of Internal Trade, Food Security and Consumer Welfare and State Minister of Defence Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi, Minister of Women & Child Affairs and Social Security and Minister of Healthcare and Indigenous Medical Services Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Small & Medium Business and Enterprise Development and Minister of Industries and Supply Chain Management Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena, State Minister of Irrigation and Rural Development Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Public Management and Accounting Hon. Piyankara Jayaratne, State Minister of Indigenous Medicine Services Hon. Mohan Priyadarshana De Silva, State Minister of Human Rights and Law Reforms ( 2 ) M. No. 3 Hon. Wimalaweera Dissanayaka, State Minister of Wildlife Resources Hon. -

Report Sri Lankan Parliament Select Committee on Natural Disasters

Report Sri Lankan Parliament Select Committee on Natural Disasters Report of Sri Lankan Parliament Select Committee on Natural Disasters The Sri Lankan Parliament Select Committee to Recommend Steps to Minimize the Damages from Natural Disasters The Mandate When the tsunami hit people in Sri Lanka were not ready. In the light of the fact that the people of Sri Lanka were not prepared to face an event of this nature and the unpredictable and destructive nature of the tsunami event, on a motion moved in Parliament on 10.02.2005 the Parliament Select Committee consisting of 21 members from all political parties represented in Parliament was appointed with a mandate to: ‘Investigate whether there was a lack of preparedness to meet an emergency of the nature of the Tsunami that struck Sri Lanka on 26th December, 2004 and to recommend what steps should be taken to ensure that an early warning system be put in place and what other steps should be taken to minimize the damage caused by similar natural disaster’. By unanimous choice of Parliament, Hon. Mahinda Samarasinghe, Chief opposition Whip of Parliament was appointed the Chairman of the Committee and the committee commenced its proceedings on February 11, 2005 and had 28 sittings up to the date of submitting this Report. The Committee heard the evidence of relevant personnel, went on field visits and participated in several local and foreign study tours. Members of the Committee: Chairman Hon. Mahinda Samarasinghe, MP Chief Opposition Whip Other Members Hon. (Mrs.) Ferial Ismail Ashraff, MP Minister of Housing and Construction Industry, Eastern Province Education and Irrigation Development Hon. -

2020 Sri Lankan Parliamentary General Election

2020 Sri Lankan Parliamentary General Election ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT 1 2020 Sri Lankan Parliamentary General Election ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT 2 The Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV) is an election observation organization that contributes to both the election monitoring process and the electoral reform process of this country. CMEV was formed in 1997 jointly by the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), the Free Media Movement (FMM), and the INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre. One of CMEV’s starting core objectives was to maintain an updated database of election violations. This objective has now been expanded to include the observation of estimated election campaign costs of political parties, independent groups and candidates contesting elections. CMEV Management : Co-Conveners : Dr. P. Saravanamuttu, Udaya Kalupathirana (Mr.), Executive Director, INFORM Seetha Ranjani, Co-Convener, Free Media Movement (FMM) Manjula Gajanayake - National Coordinator, Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV) Contact Details : Centre for Monitoring Election Violence, Colombo, Sri Lanka Phone: +94 11 2826388/+94 11 2826384 Fax: +94 11 2826146 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cmev.org Facebook: facebook.com/electionviolence Twitter: twitter.com/cmev Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/cmevsl/ 2020 Sri Lankan Parliamentary General Election: Election Observation Report Copyright © CMEV, 2020 All rights reserved. Written by: Manjula Gajanayake, National Coordinator, CMEV Designed by: Dilki Madhushika, Project Assistant, CMEV Tabulation of Election Data: Hirantha Isuranga Special Thanks: Thusitha Siriwardana and Pasan Jayasinghe Photographs by: Nirmani Gunarathne Cover Page by: Fathimath Ameena, Interns, CMEV About the Cover Page : ''A female voter arrived at Sirimavo Bandaranaike Balika Vidyalaya, Stanmore Crescent- Hall No. 01, Polling Station No. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 144. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, February 07, 2017 at 1.00 p. m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Foreign Employment Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Development Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and Chief Government Whip Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Co-existence, Dialogue and Official Languages Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Sustainable Development and Wildlife Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. Rishad Bathiudeen, Minister of Industry and Commerce ( 2 ) M. No. 144 Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration and Management Hon. (Mrs.) Chandrani Bandara, Minister of Women and Child Affairs Hon. Faiszer Musthapha, Minister of Provincial Councils and Local Government Hon. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa, Minister of Disaster Management Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Law and Order and Southern Development Hon.