Catholic Conservatives Kevin E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Justice in an Open World – the Role Of

E c o n o m i c & Social Affairs The International Forum for Social Development Social Justice in an Open World The Role of the United Nations Sales No. E.06.IV.2 ISBN 92-1-130249-5 05-62917—January 2006—2,000 United Nations ST/ESA/305 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS Division for Social Policy and Development The International Forum for Social Development Social Justice in an Open World The Role of the United Nations asdf United Nations New York, 2006 DESA The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint course of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises inter- ested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks devel- oped in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Note The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the mate- rial do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers. -

Winter 2009 Licata Lecture: Michael Novak Calls for Conversation About God

WINTER 2009 LICATA LECTURE: MICHAEL NOVAK CALLS FOR CONVERSATION ABOUT GOD And yet, he told his Pepperdine audi- ence faith is a “real knowledge—a practi- cal kind of knowledge worth trusting one’s life to.” Faith was the sustaining hope of those who struggled against totalitarian- ism in the 20th century. It is the basis for a compassionate society. Rather than con- tradicting the sciences, faith is a firm sup- Victor Davis Hanson port on which reason may flourish. 2009 William E. Simon As men and women continue to ask ques- Distinguished Visiting Professor tions about faith and secularism, people in both camps may become more tolerant of Scholar of classical civilizations, author, each other. Novak echoed the prediction columnist, and historian Victor Davis Hanson of the German philosopher Habermas that is serving as the Spring 2009 William E. we are at the “end of the secular age.” Simon Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Now, “believers and unbelievers will have School of Public Policy. He is teaching the to take each other much more seriously seminar in international relations: Global Rule than they did before.” of Western Civilization? In an era when our public discourse Hanson is a Senior Fellow in Residence in “VIRTUALLY ALL THE WORLD seems to lack civility, Novak foresees “the Classics and Military History at the Hoover end of the period of condescension” and Institution at Stanford University and IS IN THE GRIP OF QUESTIONS “the beginning of a conversation that rec- Professor Emeritus of Classics at California ABOUT GOD,”… ognizes each others’ inherent dignity.” State University, Fresno. -

The Jewish Idea: Morality, Politics, and Theology Tikvah Summer Fellowship for College Students

THE TIKVAH FUND 165 E. 56th Street New York, New York 10022 The Jewish Idea: Morality, Politics, and Theology Tikvah Summer Fellowship for College Students June 18–July 31, 2015 Calendar The Jewish Idea: Morality, Politics, and Theology June 18–21, 2015 THE MODERN JEWISH CONDITION: A CONVERSATION Thursday, June 18 Friday, June 19 Saturday, June 20 Sunday, June 21 Candle lighting at 8:12 PM Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast 9:30 AM – 10:00 AM 8:30 AM – 9:30 AM 8:45 AM – 9:30 AM Travel to Glen Cove, NY Shacharit Nationhood and Vulnerability William Kristol 10:00 AM – 12:00 PM 9:30 AM – 12:00 PM 9:30 AM – 12:00 PM Lunch Lunch Lunch and Callings and Careers III: Abe Socher 12:00 PM – 1:00 PM 12:00 PM – 1:00 PM 12:30 PM – 2:00 PM Tradition and Progress Authority and Interpretation Back to NYC Ruth Wisse Abe Socher 2:15 PM 1:00 PM – 3:30 PM 1:00 PM – 3:30 PM Callings and Careers I: Mincha William Kristol 4:00 PM – 5:30 PM 6:00 PM Welcome Dinner and Mincha, Kabbalat Shabbat, Dinner Introductions Maariv 6:30 PM Callings and Careers II: Ruth Wisse 7:00 PM – 8:15 PM 7:45 PM – 9:15 PM Dinner Havdalah 6:00 PM – 8:30 PM 8:15 PM 9:21 PM The Jewish Idea: Morality, Politics, and Theology June 22–26, 2015 REASON, REVELATION , AND MODERNITY Monday, June 22 Tuesday, June 23 Wednesday, June 24 Thursday, June 25 Friday, June 26 Candle lighting at 8:13 PM Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Writing (Tikvah is open for study and writing) 8:30 AM – 9:45 AM 8:30 AM – 9:45 AM 8:30 AM – 9:45 AM 8:30 AM – 9:45 AM “Why We Remain “Progress or Return?” I Preceptorial -

Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy

The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy Dr. Valerie Scatamburlo-D'Annibale University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada Abstract This article explores how Donald Trump capitalized on the right's decades-long, carefully choreographed and well-financed campaign against political correctness in relation to the broader strategy of 'cultural conservatism.' It provides an historical overview of various iterations of this campaign, discusses the mainstream media's complicity in promulgating conservative talking points about higher education at the height of the 1990s 'culture wars,' examines the reconfigured anti- PC/pro-free speech crusade of recent years, its contemporary currency in the Trump era and the implications for academia and educational policy. Keywords: political correctness, culture wars, free speech, cultural conservatism, critical pedagogy Introduction More than two years after Donald Trump's ascendancy to the White House, post-mortems of the 2016 American election continue to explore the factors that propelled him to office. Some have pointed to the spread of right-wing populism in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis that culminated in Brexit in Europe and Trump's victory (Kagarlitsky, 2017; Tufts & Thomas, 2017) while Fuchs (2018) lays bare the deleterious role of social media in facilitating the rise of authoritarianism in the U.S. and elsewhere. Other 69 | P a g e The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy explanations refer to deep-rooted misogyny that worked against Hillary Clinton (Wilz, 2016), a backlash against Barack Obama, sedimented racism and the demonization of diversity as a public good (Major, Blodorn and Blascovich, 2016; Shafer, 2017). -

Download Annual Report

The New Conservative Flagship ANNUAL REPORT 2020A About American Compass Table of Contents Our Mission To restore an economic consensus that emphasizes the importance of family, community, and industry to the nation’s liberty and prosperity: 1 Founder’s Letter 4 REORIENTING POLITICAL FOCUS from growth for its own sake to widely shared economic development that sustains vital social institutions. SETTING A COURSE for a country in which families can achieve self- sufficiency, contribute productively to their communities, and prepare the next 2 Year in Review 10 generation for the same. Conservative Flagship 12 HELPING POLICYMAKERS NAVIGATE the limitations that markets and government each face in promoting the general welfare and the nation’s security. Changing the Debate 14 Our Activities Creating Community 16 AFFILIATION. Providing opportunities for people who share its mission to The Commons 18 build relationships, collaborate, and communicate their views to the broader political community. Our Growing Influence 20 DELIBERATION. Supporting research and discussion that advances understanding of economic and social conditions and tradeoffs through study of history, analysis of data, elaboration of theory, and development of policy 3 Our Work 21 proposals. ENGAGEMENT. Initiating and facilitating public debate to challenge existing Rebooting the American System 22 orthodoxy, confront the best arguments of its defenders, and force scrutiny of unexamined assumptions and unconsidered consequences. Coin-Flip Capitalism 26 Our Principles Moving the Chains 30 AMERICAN COMPASS strives to embody the principles and practices of a healthy democratic polity, combining intellectual combat with personal civility. Corporate Actual Responsibility 34 We welcome converts to our vision and value disagreement amongst A Seat at the Table 38 our members. -

On Liberal and Democratic Nationhood

On Liberal and Democratic Nationhood by Paul Gottfried* The consubstantiality of liberalism and democracy has become a modem religious dogma. It is a doctrine transcending established political divisions, and ever since the de-Sovietization of Eastern Europe that began last year American journalists of otherwise differing ideological persuasions-Jeanne Kirkpatrick, Robert Novak, Ben Wattenberg, Michael Kinsley, Charles Krauthammer, Richard Cohen, and Jim Hoagland, for example-have urged the American government to nume the seeds of liberal democracy in Eastem Europe.' The synthesis for export should consist of democratic elections, the availability of equal citizenship to all residents of a country, the separa- tion of church and state, markets open to foreign investment, the introduc- tion of at least limited market economies, and enthusiastic concern for the steadily expanding list of what are styled "human rights" Distinctions between "liberalism" and "democracy" have obviously grown pass;, so much so that usually intelligent political theorists blur them without hesitation. In the May 1990 issue of Society, the Polish scholar Leszek Kolakowski, who holds professorships at both Oxford and Chicago, warns against nationalism's alliance with "spurious and fraudulent" con- cepts of democracy. Among the concepts Kolakowski fears nationalists may stray into are democratic socialism and theocracy. He thus seeks to remind his readers that democracy is incompatible with these phenomena. Rather it finds its essence in the erection of a "legal system, to guarantee both the equality in law of all citizens and the basic personal rights which include . freedom of movement, freedom of speech, freedom of associa- tion, religious freedom, and freedom to acquire property."* It may be argued that Kolakowski confounds democracy with liberalism, concepts traditionally viewed as at least discrete and possibly contradictory. -

A Sketch of Politically Liberal Principles of Social Justice in Higher Education

Phil Smith Lecture A SKETCH OF POLITICALLY LIBERAL PRINCIPLES OF SOCIAL JUSTICE IN HIGHER EDUCATION Barry L. Bull Indiana University John Rawls was probably the world’s most influential political philosopher during the last half of the 20th century. In 1971, he published A Theory of Justice,1 in which he attempted to revitalize the tradition of social contract theory that was first used by Thomas Hobbes and John Locke in the 17th century. The basic idea of this tradition was that the only legitimate form of government was one to which all citizens had good reason to consent, and Locke argued that the social contract would necessarily provide protections for basic personal and political liberties of citizens. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson charged that the English King George III had violated these liberties of the American colonists, and therefore the colonies were justified in revolting against English rule. Moreover, the Bill of Rights of the Constitution of the United States can be understood as protecting certain basic liberties—freedom of religion and expression, for example—on the grounds that they are elements of the social contract that place legitimate constraints on the power of any justifiable government. During the late 18th and 19th centuries, however, the social contract approach became the object of serious philosophical criticism, especially because the existence of an original agreement among all citizens was historically implausible and because such an agreement failed to acknowledge the fundamentally social, rather than individual, nature of human decision making, especially about political affairs. In light of this criticism, British philosophers, in particular Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, suggested that the legitimate justification of government lay not with whether citizens actually consented to it but with whether it and its policies were designed to maximize the happiness of its citizens and actually had that effect. -

A Hayekian Theory of Social Justice

A HAYEKIAN THEORY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE Samuel Taylor Morison* As Justice gives every Man a Title to the product of his honest Industry, and the fair Acquisitions of his Ancestors descended to him; so Charity gives every Man a Title to so much of another’s Plenty, as will keep him from ex- tream want, where he has no means to subsist otherwise. – John Locke1 I. Introduction The purpose of this essay is to critically examine Friedrich Hayek’s broadside against the conceptual intelligibility of the theory of social or distributive justice. This theme first appears in Hayek’s work in his famous political tract, The Road to Serfdom (1944), and later in The Constitution of Liberty (1960), but he developed the argument at greatest length in his major work in political philosophy, the trilogy entitled Law, Legis- lation, and Liberty (1973-79). Given that Hayek subtitled the second volume of this work The Mirage of Social Justice,2 it might seem counterintuitive or perhaps even ab- surd to suggest the existence of a genuinely Hayekian theory of social justice. Not- withstanding the rhetorical tenor of some of his remarks, however, Hayek’s actual con- clusions are characteristically even-tempered, which, I shall argue, leaves open the possibility of a revisionist account of the matter. As Hayek understands the term, “social justice” usually refers to the inten- tional doling out of economic rewards by the government, “some pattern of remunera- tion based on the assessment of the performance or the needs of different individuals * Attorney-Advisor, Office of the Pardon Attorney, United States Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.; e- mail: [email protected]. -

Technoprogressive Biopolitics and Human Enhancement

TechnoProgressive Biopolitics and Human Enhancement James Hughes Ph.D. Trinity College Williams 229B, 300 Summit St., Hartford, CT 06279-2106 [email protected] “TechnoProgressive Biopolitics and Human Enhancement “ in Progress in Bioethics, ed. Jonathan Moreno and Sam Berger. 2009. MIT Press. pp. 163-188. Abstract A principal challenge facing the progressive bioethics project is the crafting a consistent message on biopolitical issues that divide progressives. The regulation of enhancement technologies is one of the issues central to this emerging biopolitics, pitting progressive defenders of enhancement, "technoprogressives," against progressive critics. This essay will argue that technoprogressive biopolitics express the consistent application of the core progressive values of the Enlightenment: the right of individuals to control their own bodies, brains and reproduction according to their own conscience, under democratic states that work for the public good. Insofar as left bioconservatives want to ensure the safety of therapies and their equitable distribution, these concerns can be addressed by thorough and independent regulation and a universal health care system, and a progressive bioethics of enhancement can unite both enthusiasts and skeptics. Insofar as bioconservative concerns are motivated by deeper hostility to the Enlightenment project however, by assertion of pre-modern reverence for human uniqueness for instance, then a common program is unlikely. After briefly reviewing the political history and contemporary landscape of biopolitical debates about enhancement, the essay outlines three meta-policy contexts that will impact future biopolicy: the pressure to establish a universal, cost-effective health insurance system, the aging of industrial societies, and globalization. Technoprogressive appeals are outlined that will can appeal to key constituencies, and build a majority coalition in support of progressive change. -

Regulation As Social Justice: Empowering People Through Public Protections June 5, 2019, 9:00 A.M

Briefing Memo for Regulation as Social Justice Conference Regulation as Social Justice: Empowering People Through Public Protections June 5, 2019, 9:00 a.m. The George Washington University Law School 2000 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20052 Introduction The Center for Progressive Reform (CPR) organized Regulation as Social Justice: Empowering People Through Public Protections to serve as a wellspring for the development of a progressive vision for the future of U.S. regulatory policy. We thought it was important to bring together a diverse group of progressive advocates who are working to promote social justice for two reasons. First, we wanted to learn from your unique experiences about the challenges and opportunities the regulatory system presents for building a more just society. The variety of perspectives in turn would help to inform better solutions for reforming the regulatory system so it can do a better job of promoting social justice and addressing unmet community needs. Second, and more broadly, we hope that this event will help build new connections and strengthen existing relationships among the members of the progressive community to reinforce the broader movement to build a more just society. The goal of this memo is to stimulate participants’ thinking about the major issues that will be addressed during the conference. In particular, we see the conference as addressing two broad issues: 1. How does the U.S. regulatory system fit into the broader progressive movement to promote social justice? 2. What reforms are necessary for rebuilding the U.S. regulatory system in a manner consistent with the progressive vision of society? The Relationship Between the Regulatory System and Broader Problems with U.S. -

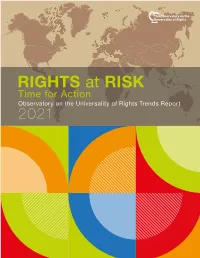

RIGHTS at RISK

RIGHTS at RISK Time for Action Observatory on the Universality of Rights Trends Report 2021 RIGHTS AT RISK: TIME FOR ACTION Observatory on the Universality of Rights Trends Report 2021 Chapter 4: Anti-Rights Actors 4 www.oursplatform.org 72 RIGHTS AT RISK: TIME FOR ACTION Observatory on the Universality of Rights Trends Report 2021 Chapter 4: Anti-Rights Actors Chapter 4: CitizenGo Anti-Rights Actors – Naureen Shameem AWID Mission and History ounded in August 2013 and headquartered Fin Spain,221 CitizenGo is an anti-rights platform active in multiple regions worldwide. It describes itself as a “community of active citizens who work together, using online petitions and action alerts as a resource, to defend and promote life, family and liberty.”222 It also claims that it works to ensure respect for “human dignity and individuals’ rights.”223 United Families Ordo Iuris, International Poland Center for World St. Basil the Istoki Great Family and Endowment Congress of Charitable Fund, Russia Foundation, Human Rights Families Russia (C-Fam) The International Youth Alliance Coalition Russian Defending Orthodox Freedom Church Anti-Rights (ADF) Human Life Actors Across International Heritage Foundation, USA FamilyPolicy, Russia the Globe Group of Friends of the and their vast web Family of connections Organization Family Watch of Islamic International Cooperation Anti-rights actors engage in tactical (OIC) alliance building across lines of nationality, religion, and issue, creating a transnational network of state and non-state actors undermining rights related to gender and sexuality. This El Yunque, Mexico visual represents only a small portion Vox party, The Vatican World Youth Spain of the global anti-rights lobby. -

What Conservative Social Justice Means to Me

University of St. Thomas Journal of Law and Public Policy Volume 3 Issue 1 Spring 2009 Article 8 January 2009 What Conservative Social Justice Means to Me Michael Boulette Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/ustjlpp Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Michael Boulette, What Conservative Social Justice Means to Me, 3 U. ST. THOMAS J.L. & PUB. POL'Y 107 (2009). Available at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/ustjlpp/vol3/iss1/8 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by UST Research Online and the University of St. Thomas Journal of Law and Public Policy. For more information, please contact the Editor-in-Chief at [email protected]. WHAT CONSERVATIVE SOCIAL JUSTICE MEANS TO ME MICHAEL BOULETTE* To be conservative, then, is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.' The question posed by the editorial board is, in fact, twofold. It must first be determined what conservatism is, and only then can we begin to comment on a properly conservative conception of social justice. This essay will attempt to answer both questions. The essay will first argue for a truly conservative conservatism, a conservatism dedicated to preserving our vital social traditions, and a traditional protectivism against the tide of progressive social thought.' Next, the essay will suggest a definition of social justice consistent with this notion of conservatism.