Louise Ans Son-~~Er.~ Science'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Etruscan Concerto

476 3222 PEGGY GLANVILLE-HICKS etruscan concerto TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA As a still relatively young nation, Australia could composing that they had no option but to go be considered fortunate to have collected so away. Equally true, relatively few of our few notable dead composers! For most of the composing women flourished ‘abroad’ for long, 20th century, almost every composer we could though Tasmanian Katharine Parker (Longford- claim was very much alive. Yet, sadly, this did born and Grainger protégée) did, and Melburnian not stop us from losing track of some of our Peggy Glanville-Hicks is the notable other. Peggy Glanville-Hicks 1912-1990 most talented, who went away and stayed Indeed, Edward Cole’s notes for the 1956 away, as did Percy Grainger and Arthur Benjamin American first recording of her Etruscan Etruscan Concerto [15’17] (the only Australian composer blacklisted by Concerto make the unique claim: ‘Peggy 1 I. Promenade 4’05 Goebbels), or returned too late, like Don Banks. Glanville-Hicks is the exception to the rule that 2 II. Meditation 7’26 And we are now rediscovering many other women composers do not measure up to the 3 III. Scherzo 3’46 interesting stay-aways, like George Clutsam (not standards set in the field by men.’ Caroline Almonte piano just the arranger of Lilac Time), Ernest Hutchinson, John Gough (Launceston-born, like Talented Australian women of Glanville-Hicks’ 4 Sappho – Final Scene 7’42 Peter Sculthorpe) and Hubert Clifford. generation hardly lacked precedent for going Deborah Riedel soprano Meanwhile, among those who valiantly toiled abroad, as Sutherland, Rofe and Hyde all did for away at home, we are at last realising that a while, with such exemplars as Nellie Melba 5 Tragic Celebration 15’34 names like Roy Agnew, John Antill and David and Florence Austral! Peggy Glanville-Hicks’ Letters from Morocco [14’16] Ahern might not just be of local interest, but piano teacher was former Melba accompanist 6 I. -

Women in the Creative Arts Conference Australian National University, 10-12 August 2017

Women in the Creative Arts conference Australian National University, 10-12 August 2017 ~SCHEDULE~ as at 2 August 2017 http://music.anu.edu.au/news/women-creative-arts THURSDAY 10 AUGUST 2017 9.00 – 10.30am Conference Registration | Athenaeum, School of Music (ground level) Foster Larry Sitsky Recital Room Lecture Theatre 1 Lecture Theater 3 Room SESSION 1A SESSION 1B SESSION 1C Muses Trio Performance Practice Dance and the body Chair - Prof. Cat Hope Chair – Dr. Julie Rickwood 10.30am Jacinta Dennett Jane Ingall (Somebody’s Aunt) (University of Melbourne) Somebody's Aunt - dancing the personal Illuminating Significative Utterance in and the political Performance: Helen Gifford’s Fable (1967) for Harp 11.00am Emily Bennett Carolyn McKenzie-Craig (University of Melbourne) (National Art School) Muses Trio The machine and the message; the role Performative modes of research and rehearsal of electronic sound processing in Jenny practice in the work of feminist (closed), no Hval’s vocal performance art practice collective Bruce and Barry composers 11.30am Janet McKay Emma Townsend (University of Queensland) (University of Melbourne) Dreams, Layers, Obsessions: A flutist’s Confirming, contesting and unsettling role in collaboration with four female compositional gender stereotypes in the composers ballet Sea Legend by Esther Rofe 12.00 – 1.00pm LUNCH | Athenaeum, School of Music (ground level) (ARC Cinema, National Film and Foster Larry Sitsky Recital Room Lecture Theatre 1 Sound Archive, Canberra) 2C only Room SESSION 2A SESSION 2B SESSION -

Australian Chamber Music with Piano

Australian Chamber Music with Piano Australian Chamber Music with Piano Larry Sitsky THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Sitsky, Larry, 1934- Title: Australian chamber music with piano / Larry Sitsky. ISBN: 9781921862403 (pbk.) 9781921862410 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Chamber music--Australia--History and criticism. Dewey Number: 785.700924 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Preface . ix Part 1: The First Generation 1 . Composers of Their Time: Early modernists and neo-classicists . 3 2 . Composers Looking Back: Late romantics and the nineteenth-century legacy . 21 3 . Phyllis Campbell (1891–1974) . 45 Fiona Fraser Part 2: The Second Generation 4 . Post–1945 Modernism Arrives in Australia . 55 5 . Retrospective Composers . 101 6 . Pluralism . 123 7 . Sitsky’s Chamber Music . 137 Edward Neeman Part 3: The Third Generation 8 . The Next Wave of Modernism . 161 9 . Maximalism . 183 10 . Pluralism . 187 Part 4: The Fourth Generation 11 . The Fourth Generation . 225 Concluding Remarks . 251 Appendix . 255 v Acknowledgments Many thanks are due to the following. -

An Australian Composer Abroad: Malcolm Williamson And

An Australian Composer Abroad: Malcolm Williamson and the projection of an Australian Identity by Carolyn Philpott B.Mus. (Hons.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Conservatorium of Music University of Tasmania October 2010 Declaration of Originality This dissertation contains no material that has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University of Tasmania or any other institution, except by way of background information that is duly acknowledged in the text. I declare that this dissertation is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no material previously published or written by another person except where clear acknowledgement or reference is made in the text, nor does it contain any material that infringes copyright. This dissertation may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Carolyn Philpott Date ii Abstract Malcolm Williamson (1931-2003) was one of the most successful Australian composers of the latter half of the twentieth century and the depth, breadth and diversity of his achievements are largely related to his decision to leave Australia for Britain in the early 1950s. By the 1960s, he was commonly referred to as the “most commissioned composer in Britain” and in 1975 he was appointed to the esteemed post of Master of the Queen’s Music. While his service to music in Britain is generally acknowledged in the literature, the extent of his contribution to Australian music is not widely recognised and this is the first research to be undertaken with a strong focus on the identification and examination of the many works he composed for his homeland and his projection of an Australian identity through his music and persona. -

Download (2MB)

- i - - ii - UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND The Impact of Australian Classical Music Record Labels on the Australian Music Scene A Dissertation submitted by Nicola N Hayden For the award of Master of Music May 2009 - iii - Abstract The impact of Australian classical music record labels on the Australian music scene is investigated in terms of the awareness and development of Australian classical music amongst the musical community, the careers of Australian composers and performers, and the investigation into which particular label is thought to have played the most prominent role in this regard. A review of those labels currently in production in Australia was undertaken and includes the labels ABC Classics, Australian Eloquence, Jade, Melba Recordings, Move Records, Solitary Island Records, Sydney Symphony, Tall Poppies, Revolve, Vox Australis, and Walsingham Classics. The aims and goals of the various labels are ascertained along with the nature of the catalogues of each label. A comprehensive survey of each catalogue is undertaken with reference to the content of Australian compositions represented on each label. In this regard Tall Poppies label represents the most Australian composers. A survey of members of the Australian musical community was undertaken in relation to the research aims. Responses were elicited regarding the level of the respondents‘ awareness of the existence of these labels and to measure the impact the labels have had on the respondents‘ knowledge of Australian classical music. In both cases it was confirmed that Australian classical record labels have increased the respondents‘ awareness and appreciation of Australian music. Composers who have had their works recorded on an Australian record label and performers whose performances have been recorded on such labels were asked to indicate how this experience had helped them in the launching or furthering of their careers. -

LYREBIRD COMMISSION with CONCERT CALENDAR CRANIA BURKE, Clarinets

The British Music Society of Victoria Inc. was founded in 1921 by Mrs Louise Dyer. Applications for membership are most welcome. BRITISH Ask for our brochure. Annual Subscriptions: $60 (Adult) $40 (Concession) MUSIC $80 (Family) (Renewable on anniversary of initial subscription) Members are admitted free to all Society recitals. SOCIETY INC. General Admission $20 ($10 concession) Enquiries: Rosemary Mclndoe 100/264 Springvale Road NUNAWADING VIC 3131 Ph.9877 2650 Email: [email protected] LYREBIRD COMMISSION with CONCERT CALENDAR CRANIA BURKE, clarinets Sunday November 4th 2pm 2007 KIRSTY BREMNER, violin Sunday December 2nd 5pm* 2007 Sunday March 2nd 2pm 2008 DAVID McNICOL, pianoforte Sunday April 6th 2pm 2008 Sunday May 4th 2pm 2008 Sunday June 1st 2pm 2008 Sunday July 6th 2pm 2008 ,rd Sunday August 3r 2pm 2008 Sunday September 7th 2pm 2008 Sunday THE CHAPEL Sunday October 5th 2pm 2008 October 7th COPPIN COMMUNITY CENTRE *denotes early evening performance time ROYAL FREEMASONS' HOMES 2007 Cnr. Punt & Moubray St NEXT RECITAL: 2.00pm (enter from Moubray St) Sunday November 4* at 2pm Melway Ref: 2L D10 Ivana Tomaskova, violin Tamara Smolyar, pianoforte Meet the Artists the official accompanist for a number of Australia's most prestigious singing competitions, CRANIA BURKE...CLARINET/BASS CLARINET. Grania is a Melbourne based including the Herald Sun Aria Final, the German-Australian Operatic Award, the Welsh clarinettist/bass clarinettist and educator. She has performed regularly with the Melbourne Singer of the Year Award and the Lieder Society's "Liederfest". David has appeared as a Symphony Orchestra, Orchestra Victoria, Australian Philharmonic Orchestra and Chamber piano soloist and as an accompanist in a number of live, national-broadcasts for 'ABC Made Opera. -

Tocc0470booklet.Pdf

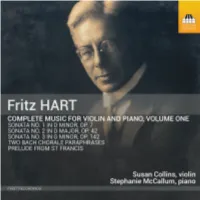

FRITZ HART: MUSIC FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO, VOLUME ONE by Peter Tregear Born in Brockley, South London, Fritz Bennicke Hart (1874–1949) stands as one of the more extraordinary figures of the so-called English Musical Renaissance, all the more so because he remains so little known. His mother was a piano teacher from Cornwall and his father a travelling salesman of Irish ancestry born in East Anglia. The eldest of five, Hart was not encouraged to pursue a musical career as a child, but piano lessons from his mother were later complemented by the award of a choristership at Westminster Abbey, then under the direction of Frederick Bridge – ‘Westminster Bridge’, as he was inevitably nicknamed. A year earlier Bridge had been appointed professor of harmony and counterpoint at the newly constituted Royal College of Music and in 1893 Hart would join him there as a student of piano and organ. In addition, in the years between his tenure as a chorister and his enrolling at the RCM, Hart had been introduced to both the music and the aesthetic philosophy of Richard Wagner and had also become a regular and enthusiastic audience member of the Saturday orchestral concerts held at the Crystal Palace and the RCM. It seems Hart quickly became better known at the RCM for his ardent interest in opera and music drama than for his piano-playing. Indeed, Imogen Holst credits Hart with having introduced her father, Gustav, to Wagner.1 But unlike Holst and other contemporaries, such as Ralph Vaughan Williams, John Ireland, Samuel Coleridge- Taylor and William Hurlstone, Hart did not formally study composition. -

Light Music in the Practice of Australian Composers in the Postwar Period, C.1945-1980

Pragmatism and In-betweenery: Light music in the practice of Australian composers in the postwar period, c.1945-1980 James Philip Koehne Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide May 2015 i Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. _________________________________ James Koehne _________________________________ Date ii Abstract More than a style, light music was a significant category of musical production in the twentieth century, meeting a demand from various generators of production, prominently radio, recording, film, television and production music libraries. -

Composing Biographies of Four Australian Women: Feminism, Motherhood and Music

COMPOSING BIOGRAPHIES OF FOUR AUSTRALIAN WOMEN: FEMINISM, MOTHERHOOD AND MUSIC Jillian Graham (BMus, MMus) Thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2009 Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne This thesis is dedicated with love to my children and to my mother Olivier and Freya Miller Pamela Graham ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the impact of gender, feminism and motherhood on the careers of four Australian composers: Margaret Sutherland (1897–1984), Ann Carr-Boyd (b. 1938), Elena Kats-Chernin (b. 1957) and Katy Abbott (b. 1971). Aspects of the biographies of each of these women are explored, and I situate their narratives within the cultural and musical contexts of their eras, in order to achieve heightened understanding of the ideologies and external influences that have contributed to their choices and experiences. Methodologies derived from feminist biography and oral history/ethnography underpin this study. Theorists who inform this work include Marcia Citron, Daphne de Marneffe, Sherna Gluck, Carolyn Heilbrun, Anne Manne, Ann Oakley, Alessandro Portelli, Adrienne Rich and Robert Stake, along with many others. The demands traditionally placed on women through motherhood and domesticity have led to a lack of time and creative space being available to develop their careers. Thus they have faced significant challenges in gaining public recognition as serious composers. There is a need for biographical analysis of these women’s lives, in order to consider their experiences and the encumbrances they have faced through attempting to combine their creative and mothering roles. Previous scholarship has concentrated more on their compositions than on the women who created them, and the impact of private lives on public lives has not been considered worthy of consideration. -

AITCHISON TRAVELLING SCHOLARSHIP List of Holders Note. Until 1940 This Scholarship Was Awarded Every Second Year. from That Date

AITCHISON TRAVELLING SCHOLARSHIP List of Holders Note. Until 1940 this scholarship was awarded every second year. From that date income from the Myer and other funds was used to supplement the income from the Aitchison fund so that itcoul d be granted every year. From 1950 the scholarship was known as the Aitchison-Myer scholarship and the income in the first year was found from the Aitchison bequest and in the second year from the Myer bequest. Year Awarded to Department 1927 Cornell, G. French 1929 Massey, H.S.W. Physics 1931 McNab, J.R. Classics 1933 Love, E.R. Mathematics 1935 Home, CJ. English 1937 Kerford, G.B. Classics Scott, W.A.G. 1939 taken up in 1946 English Batchelor, G.K 1941 taken up in 1945 Mathematics Churchward, L.G. 1942 taken up in 1948 for one year History Karmel, P.H. 1943 taken up in 1947 Economics McBriar, A.M. 1944 taken up in 1946 History 1946 Dalitz, R.H. Mathematics 1947 Ransford, G.D. Civil Engineering Hurst, CA. 1948 Mathematics held for one year 1949 Goldberg, S. English 1950 Tanner, R.G. Classics 1951 Groves, M.C History 1952 Lawler, J.R. French 1953 Kennedy, D.E. History 1954 Roe, I.M. History 1955 Harcourt, G.C Economics Shaw, B.J. 1956 Law held for one year 1957 Robertson, I.G. History 1958 Barraclough, C.G. Chemistry 1959 Clunies-Ross, A.I. History Anderson, D.R.C. 1960 Political Science held for one year 1961 Johanson, D.F.C History 1962 Forster, K.I. Psychology 1963 Goss, B.A. -

Chapter 1: Epistemological Disjuncture Within the Literature on Geoffrey Powell

Forged under the Hammer and Sickle: The Case of Geoffrey Powell, 1945–1960 Author Hoehne, Craig John Published 2016 Thesis Type Thesis (Masters) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/912 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366519 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Forged under the Hammer and Sickle: The Case of Geoffrey Powell, 1945–1960 Mr Craig John Hoehne Griffith Film School Queensland College of Art Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Visual Arts <May 2016> Synopsis Forged under the Hammer and Sickle, The Case of Geoffrey Powell 1945– 1960 is a multimodal exhibition and exegesis that concerns the post-war production of photographer-turned-documentary-filmmaker Geoffrey Powell (1918–1989). It re- evaluates Powell's production through the prism of his socio-political evolution from reactionary to Marxist. Within the photo-historical literature, he is defined as a participant in the mainstream Post-War Documentary Movement in photography. However, my research has revealed that Powell belonged to a cross- disciplinary nexus of creative thought. He was a member of the Australian Communist Party and his photographic production was all but confined to Socialist Realist journals. This Marxist affiliation imposed strictures on the way in which he engaged with subjects as well as the aesthetics of his work. He was also an active participant on the progressive ‘Arts Front’. An interest in expository film by the progressive Left tweaked a curiosity in Powell, which ultimately encouraged his move into documentary filmmaking. -

Melba Music Concert

PRESBYTERIAN LADIES’ COLLEGE Old Collegians’ Association MELBA MUSIC CONCERT SATURDAY 21 MARCH 2020 AT 3PM Celebrating the 145th Anniversary of Music at PLC PLC PERFORMING ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 1 WELCOME I have been so inspired by the enthusiasm and generosity of all our Old Collegian musicians who have joined together today, to entertain us and to raise money for the OCA Melba Music Scholarships. For my hardworking OCA Committee, after 18 months of planning the dream of holding a concert in the new PAC has become a reality. A very special thank you to all our talented musicians and the numerous Old Collegians who have joined together to make this concert happen. In particular I thank our Concert Coordinator, Dr Ros McMillan (1959), our co-comperes Peter Ross and Lisa Leong (1989), our backstage team, our ushers and our refreshments team. A special thank you to the Principal for making the PAC available and also for all the support we have received from PLC Departments including Audio Visual, Publications, the Print Office and the Development Office. Special thanks should go to PLC’s Heritage Centre Manager, Janet Davies (1980), who has provided the story of our rich music heritage with photo boards and key dates, and PLC Archivist Jane Dyer. Please join us in celebrating this event. Ailsa Wilson President, PLC Old Collegians’ Association Music has played an important part in PLC life for 145 years. From the earliest days of the school it has been regarded as an essential aspect of the education of all its students. Today’s concert showcases over 40 musicians, mostly past students or music staff, whose links with PLC cover more than 70 years, from the late 1940s through every decade to the present.