Exploring the Lives of Gifted Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liebman Expansions

MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE LIEBMAN EXPANSIONS CHICO NIK HOD LARS FREEMAN BÄRTSCH O’BRIEN GULLIN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Chico Freeman 6 by terrell holmes [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Nik Bärtsch 7 by andrey henkin General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Dave Liebman 8 by ken dryden Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Hod O’Brien by thomas conrad Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Lars Gullin 10 by clifford allen [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Rudi Records by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above CD Reviews or email [email protected] 14 Staff Writers Miscellany David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, 37 Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Event Calendar 38 Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Tracing the history of jazz is putting pins in a map of the world. -

Music and Militarisation During the Period of the South African Border War (1966-1989): Perspectives from Paratus

Music and Militarisation during the period of the South African Border War (1966-1989): Perspectives from Paratus Martha Susanna de Jongh Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Stephanus Muller Co-supervisor: Professor Ian van der Waag December 2020 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 29 July 2020 Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract In the absence of literature of the kind, this study addresses the role of music in militarising South African society during the time of the South African Border War (1966-1989). The War on the border between Namibia and Angola took place against the backdrop of the Cold War, during which the apartheid South African government believed that it had to protect the last remnants of Western civilization on the African continent against the communist onslaught. Civilians were made aware of this perceived threat through various civilian and military channels, which included the media, education and the private business sector. The involvement of these civilian sectors in the military resulted in the increasing militarisation of South African society through the blurring of boundaries between the civilian and the military. -

Recommended Listening List

RECOMMENDED LISTENING LIST This list is obviously not a comprehensive listening list. It is intended to be a starting point for the student’s discovery, education and enjoyment. This list has been EXTREMELY condensed to account for page numbers… keep exploring!!! (Jazz Albums, except for big bands, are categorized by the instrument played by the leader.) JAZZ • Thrust * Kenny Werner: Chick Corea: • Beat Degeneration PIANO • Now He Sings Now He Bud Powell: Sobs* Steve Kuhn • Three Quartets* • The Amazing Bud • Steve Kuhn Trio- Powell, Volume 1* McCoy Tyner: Life’s Magic Thelonious Monk: • The Real McCoy* Ellis Marsalis • Misterioso * Dave Brubeck: • The Classic Ellis • Live at the Five Spot * Marsalis • Monk’s Music* • Time Out • Thelonious Monk Quartet With John Geri Allen: SAXOPHONE Coltrane: Live At Carnegie Hall* • In The Year of The Sonny Rollins: Dragon Oscar Peterson Trio: • The Nurturer • Live at the Village Vanguard * • Oscar Peterson Trio + 1 Keith Jarrett: • Saxophone Colossus* Red Garland: • Standards Volume 1 and • Way Out West* 2 * • Groovy • Changes * Joe Henderson: • Standards Live * Ahmad Jamal: • Tribute* • Inner Urge* • Belonging* • Power To The People* • Ahmad’s Blues* • The Cure * • The State Of The Tenor * Bill Evans Michel Camilo: Wayne Shorter: • Waltz for Debby * • Michel Camilo • Live at the Village • Live At The Blue Note • Speak No Evil * Vanguard * • Ju-Ju* Brad Mehldau: Herbie Hancock: Oliver Nelson: • Brad Mehldau Trio Live • Maiden Voyage * • Blues and The Abstract • Empyrean Isles* Truth* • Headhunters -

Chaco's Place in the Formalized Landscape.Pdf

CHACO’S PLACE IN THE FORMALIZED LANDSCAPE DESIGN AND SURVEYING OF LARGE SCALE GEOMETRIES AS Hopi ceremonial instrument RITUAL PRACTICE DENNIS DOXTATER - UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA Biographic Note The author is a licensed architect with professional academic and practice experience in architecture and landscape architecture. A professional Bachelor of Architecture is from the University of Washington, Seattle, with a M.A. in Socio-Cultural Anthropology at the same institution. A Doctor of Architecture comes from an interdisciplinary program at the University of Michigan. Present status is Professor Emeritus in the College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture at the University of Arizona. The ancestral Doxtater name is Oneida Indian. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 READING THIS BOOK FROM DIFFERENT BACKGROUNDS 3 Social organization 3 Introducing probability comparisons between existing and random patterns 4 “Reading” the design analyses 6 A note to archaeologists 9 1. Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Formalized Large Scale Ritual 11 Frameworks in the Landscape Shamanistic use of “web” structures in the landscape 11 Ritually used cross frameworks in the larger landscape 26 Archaeological interpretations of the interim between shamanistic and 32 historic landscapes Possible origins of ritual landscape cross structures on the Southern Colorado 39 Plateau 2. Probability Comparisons: Alignment Involvement of Great Kiva 51 Locations Existing literature on random comparisons 51 Influence of large scale natural topography on alignments 52 Natural features used in the analysis 57 Locations of great kiva sites 58 Comparing BMIII/PI and PII/PIII 70 3. A Surveyed East Meridian and First Triadic Structure of Chaco 79 The first built ceremonial site as mediator of a large scale bipolar line 84 Intercardinal axes and a triadic ritual definition in Chaco Canyon 86 Great kiva linkage to the landscape: “villages” in the West 93 PROBABILITY TEST: THE MOUNT WILSON MERIDIAN 97 4. -

Marcus Belgrave 2009 Kresge Eminent Artist 2009 Kresge Eminent Artist 1

Belgrave 2009 Marcus Kresge Eminent Artist Eminent Kresge Marcus Belgrave 2009 Kresge Eminent Artist 2009 Kresge Eminent Artist 1 Contents FOREWORD 3 Rip Rapson President and CEO, The Kresge Foundation PORTRAIT OF AN ARTIST 7 A Syncopated Journey by Claudia Capos 10 The Life and Be-Bop Times of Marcus Belgrave: A Timeline MASTER OF THE MUSIC 19 The Early Years: On the Road with Ray by W. Kim Heron “I want to see the music 20 Jazzin’ Up Motown by Sue Levytsky 22 Key Change: Evolution into the Avant-Garde by W. Kim Heron 24 Back to Big Time, Good Time, Old Time Jazz by Sue Levytsky of America continue. 27 Selected Belgrave Discography We have so much to give. Our music PASSING ON THE TRADITION 32 Marcus – The Master Teacher by Herb Boyd keeps coming, bubbling up 37 The Lesson Plan by W. Kim Heron 38 The Belgrave Method: Students Take Note from a reservoir. I’m happy to have been 39 A Letter in Tribute from Anne Parsons and The Detroit Symphony Orchestra a vital part of an era, 40 Teach Your Children Well 44 Belgrave as Educator and I want to see it endure.” 46 Selected Achievements, Awards, and Recognitions – Marcus Belgrave KRESGE ARTS IN DETROIT 48 The Kresge Eminent Artist Award 48 Charles McGee: 2008 Kresge Eminent Artist 49 A Letter of Thanks from Richard L. Rogers and Michelle Perron College for Creative Studies 50 Kresge Arts in Detroit – Advisory Council 51 About The Kresge Foundation 51 The Kresge Foundation Board of Trustees 52 Acknowledgements LISTEN TO ”Marcus Belgrave: Master of the Music” THE ACCOMPANYING CD INSERTED INTO THE BACK COVER. -

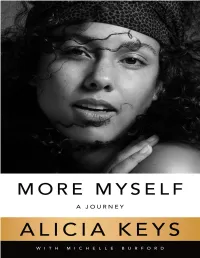

Alicia Keys, Click Here

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Authors Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on Alicia Keys, click here. For email updates on Michelle Burford, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. This book is dedicated to the journey, and all the people who are walking with me on it … past, present, and future. You have all helped me to become more myself and I am deeply grateful. FIRST WORD The moment in between what you once were, and who you are now becoming, is where the dance of life really takes place. —Barbara De Angelis, spiritual teacher I am seven. My mom and I are side by side in the back seat of a yellow taxi, making our way up Eleventh Avenue in Manhattan on a dead-cold day in December. We hardly ever take cabs. They’re a luxury for a single parent and part-time actress. But on this afternoon, maybe because Mom has just finished an audition near my school, PS 116 on East Thirty-third Street, or maybe because it’s so freezing we can see our breath, she picks me up. -

Women, Gender and Identity in Popular Music-Making in Gauteng

Women, Gender and Identity in Popular Music-Making in Gauteng, 1994 - 2012 by Ceri Moelwyn-Hughes A dissertation submitted for the degree of Master of Music in the Wits School of Arts, Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand ABSTRACT Women, Gender and Identity in Popular Music-Making in Gauteng, 1994 - 2012 This thesis offers an ethnographic study of the professional lives of twenty-eight women musicians working in Gauteng and their experiences in popular music-making in post- apartheid South Africa. The study is based primarily on interviews with a spectrum of women working as professional musicians, mostly as performers, but also in varied roles within the music industry. I focus on various aspects of women musicians' personal reports: identify patterns of experience in their formative years; discuss seminal relationships that influence their music-making; and note gender stereotypes, identifying and commenting on their effect on individuals. Feminist, cultural, post-colonial, musicological and ethnomusicological theory informs the empirical research and is used to interrogate meanings of identity, stereotypes about women on stage and strategies of performance that women adopt. The experiences of these twenty-eight women demonstrate that gender both positively and negatively affects their careers. Women are moving into previously male-dominated areas of contemporary music-making in South Africa such as jazz and playing certain instruments, both traditionally considered to be in the ‘male’ domain. However, despite women’s rights being well protected under current legislation, women in South Africa do not access legal recourse available to them in extreme situations of sexual harassment in the music industry. -

International Trumpet Guild® Journal

Reprints from the International Trumpet Guild ® Journal to promote communications among trumpet players around the world and to improve the artistic level of performance, teaching, and literature associated with the trumpet MARCUS BELGR AVE ON TEACHING AND PLAYING BY HONORING THE PAST BY THOMAS ERDMANN June 2009 • Page 51 The International Trumpet Guild ® (ITG) is the copyright owner of all data contained in this file. ITG gives the individual end-user the right to: • Download and retain an electronic copy of this file on a single workstation that you own • Transmit an unaltered copy of this file to any single individual end-user, so long as no fee, whether direct or indirect is charged • Print a single copy of pages of this file • Quote fair use passages of this file in not-for-profit research papers as long as the ITGJ, date, and page number are cited as the source. The International Trumpet Guild ® prohibits the following without prior writ ten permission: • Duplication or distribution of this file, the data contained herein, or printed copies made from this file for profit or for a charge, whether direct or indirect • Transmission of this file or the data contained herein to more than one individual end-user • Distribution of this file or the data contained herein in any form to more than one end user (as in the form of a chain letter) • Printing or distribution of more than a single copy of the pages of this file • Alteration of this file or the data contained herein • Placement of this file on any web site, server, or any other database or device that allows for the accessing or copying of this file or the data contained herein by any third party, including such a device intended to be used wholly within an institution. -

Downbeat's July

JULY 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

The Ten Types of Human

THE TEN TYPES OF HUMAN THE TEN TYPES OF HUMAN A New Understanding of Who We Are Dexter Dias WILLIAM HEINEMANN: LONDON 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 William Heinemann 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road London SW1V 2SA William Heinemann is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com. Copyright © Dexter Dias 2017 Dexter Dias has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published by William Heinemann in 2017 www.penguin.co.uk A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 9781785150166 (Hardcover) ISBN 9781785150173 (Trade paperback) Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, St Ives PLC Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper. For Katie, Fabi and Hermione CONTENTS Author’s note xi Prologue xvii Part I: The Perceiver of Pain 1 1: The Argument 3 2: The 21,000 15 3: Here Be Dragons 21 4: A More Total Darkness 27 5: Once I Was Blind 38 6: The Rule of Effective Invisibility 45 7: The Cognitive Cost of Compassion 52 8: The Promise 64 9: The Blank Face of Oblivion 75 vii the te te o huma Part II: The Ostraciser 87 1: Take Elpinice and Go 89 2: The Wounded City 107 3: Do Not Read This 114 4: The Circle and the Suffering 122 Part III: The Tamer of Terror 137 1: The Time Has Come 139 2: The Broken Circuit 151 3: The Case of Schwarzenegger’s Farm 165 4: The Ice -

Ginger Baker Bill Mchenry

OCTOBER 2013 - ISSUE 138 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM Space SUN In RA Time MARIAN IN MEMORIAM 1918-2013 MCPARTLAND GINGER ••••BILL MARCUS BETHLEHEM EVENT BAKER MCHENRY BELGRAVE RECORDS CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm SPECIAL EVENTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Oct 4 & 5 MIKE LEDONNE’S GROOVER QUARTET Sundays, Oct 6 & 13 JIMMY GREENE QUARTET MEETS THE GUITARISTS SaRon Crenshaw Band CD Release Preview Tue, Oct 1 Sundays, Oct 20 & 27 Jimmy Greene (tenor saxophone) ● Renee Rosnes (piano) Vivian Sessoms Ben Wolfe (bass, fri) ● John Patitucci (bass, sat) Bob Devos w/Eric Alexander & Carl Allen Jeff “Tain” Watts (drums) Tue, Oct 8 Mondays, Oct 7 & 21 Fri & Sat, Oct 11 & 12 Dave Stryker w/Vincent Herring & Joe Farnsworth Jason Marshall Big Band MONK BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION Tue, Oct 15 Mondays, Oct 14 & 28 featuring Orrin Evans Paul Bollenback w/Eric Alexander & Joe Farnsworth Captain Black Big Band Eddie Henderson (trumpet) ● Tim Warfield (tenor saxophone) Thursdays, Oct 3, 10, 17, 24 & 31 Orrin Evans (piano) ● Ben Wolfe (bass) ● Donald Edwards (drums) Tue, Oct 22 Ed Cherry w/Eric Alexander & Joe Farnsworth Gregory Generet Fri & Sat, Oct 18 & 19 Tue, Oct 29 MYRON WALDEN MOMENTUM Peter Bernstein w/Eric Alexander & Joe Farnsworth LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Darren Barrett (trumpet) ● Myron Walden (tenor saxophone) Eden Ladin (piano) ● Yasushi Nakamura (bass) ● Mark Whitfield, Jr. (drums) -

Opnieuw Eenentwintig

IN TE R VI EW GERI ALLEN opnieuw eenentwintig Volgens velen is Geri Allen de pianiste van de toekomst en misschien wel van het moment. Een portret aan de vooravond van haar komst naar ons land. „Ik ben vrij, ik kan helemaal opnieuw beginnen.” raten met Geri Allen, het vraagt DOOR ROB LEURENTOP van producer Barry Gordy, niet alleen veel geduld. Een paar zinnen tij naar plaatjes van Charlie Parker. „Wij wa dens de pauze in de Village ren dol op de Motown sound. The Supre- Vanguard, de beroemdste en mes, Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder en zo. donkerste jazzklub van New Zij vindt het fantastisch, de hele tijd nieu En James Brown. Mijn favoriete nummer York. Twee minuten backstage we plekken zien, andere mensen ontmoe was Family Affair van Sly & The Family na een koncert op Jazz Middel- ten. Binnenkort is het voorbij, dan moet ze Stone. Maar ik droomde er nooit van om heim, korte gedachtenwisselin naar school. Dat wordt ook een hele ver een zangeres te worden of een popster. Ik gen op andere festivals. andering in mijn leven, want dan accep had altijd wel het idee dat ik piano wilde Nu de pianiste naar België komt, wordt teer ik alleen nog koncerten in periodes spelen en iets in de jazzmuziek zou doen.” hetP tijd om de stukjes van de puzzel in el dat zij vakantie heeft.„S/u' will always be Maar het bloed kruipt waar het niet gaan kaar te passen. Natuurlijk, er zijn nog vra number one on my list." kan : „Wallace hoort een heleboel Mo gen.