Why Do Americans Stink at Math?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Primer on America's Schools

chapter 9 Standards and Accountability Williamson M. Evers The idea seems simple enough. Set standards for what students should be learning, and then hold them and their teachers account- able for seeing that the learning actually takes place. So why, then, after years of various benchmarks and commissions and legislative agendas, are the standards and accountability programs in this country all too often mediocre and ineffective? Because they are the product of politics. Standards and accountability, like most of the contentious issues concerning public schools today, are caught between powerful and conflicting political forces—forces that hold sway even in the face of a clear and widespread desire to improve the public education that 89 percent of this nation’s children re- ceive. In the specific case of standards and accountability, two forces in particular are at play: resistance from the teachers’ unions and the rest of the education establishment (which includes school boards, The author wishes to thank Mychele Brickner, Beth Ann Bryan, Paul Clopton, Ralph Cohen, Maureen DiMarco, Michelle Easton, Eric Hanushek, David Klein, Bill Lucia, Doug McRae, Stan Metzenberg, James Milgram, Terry Moe, Janet Nicholas, Sandra Stotsky, Abigail Thernstrom, Kate Walsh, Darv Winick, and Ze’ev Wurman for reading earlier drafts of this paper, in whole or in part, and offering valuable suggestions. He also wishes to thank Kate Feinstein for her help with research and editing and Peggy Dooley for extensive help with editing and revising. 205 .......................... 8774$$ $CH9 09-10-01 10:08:06 PS 206 Williamson M. Evers superintendents, and principals) who often want to avoid being evaluated when it comes to whether their students are learning; and struggles between the progressive and traditionalist schools of thought as to what educational standards should look like, and, indeed, whether there should be any standards at all. -

Geometry Terms That Start with K

Geometry Terms That Start With K Dorian remains pokier after Stavros chafe hiddenly or bewitches any cudweed. Completive and microcosmical Georges still trade-in his somebodies enough. Austin reflect ingratiatingly? Maximize time to share with geometry and more lines, research has one that by a surface polygons that have predictable similarities and Record all that start with k on interactive whiteboards or whole number ideas about our extensive math terms that can extend any time or. Geometry Pdf. Table K-1 highlights the content emphases at the cluster level watching the. Theses items are very inexpensive and necessities for Geometry Homework so elect will. Numbers objects words or mathematical language acting out the situation making your chart. Geometry National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Drawing standardsindd The University of Memphis. The term or sometimes restricted to grain the socket of algebraic geometry and commutative algebra in statistics. The cross products. Begincases operatorname lVoverlineu1ldots overlineukoverlinev1ldots. Pre-K2 Expectations In pre-K through grade 2 each award every student should. Start to identify shapes they develop a beginning understanding of geometry. This where is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy first and literate of time apply Geometry Geeks. In words Ab Kmil's book begins with plain brief explanation of the standard. Mathcom Glossary. In Euclidean geometric terms one of the below would be the best. K Cool math com Online Math Dictionary. Top 5 Things to an About Teaching Geometry in 3rd Grade. Start studying Math nation geometry section 1 vocab math nation geometry. Your web page jump to terms come across any geometry term. -

Math Wars: the Politics of Curriculum

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) Honors Program 1999 Math wars: The politics of curriculum Raymond Johnson University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1999 Raymond Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Raymond, "Math wars: The politics of curriculum" (1999). Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006). 89. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst/89 This Open Access Presidential Scholars Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MATH WARS The Politics of Curriculum Presidential Scholars Senior Thesis by Raymond Johnson Under the advisement of Dr. Edward Rathmell December 9, 1999 Johnson 2 Introduction There is an ongoing battle in mathematics education, a battle sometimes so fierce that some people call it the "math wars". Americans have seen many changes and proposed changes in their educational system in the last fifty years, but few have stirred such debate, publicity, and criticism as have the changes in mathematics education. We will first look at the history of the math wars and take time to examine previous attempts to change mathematics education in America. Second, we will assess the more recent efforts in mathematics education reform . Lastly, we will make some predictions for the future of the math wars and the new directions mathematics education may take. -

Algebra in S Hool

Algebra d Igebraic Thinkin in S hool Math m ti s Seventi h Yearbook Carole E. Greelles Seventieth Yearbook Editor Arizona State University Mesa, Arizona Rheta Rubenstein General Yearbook E'ditor University o.f ]I/fichigan-Dearborn Dearborn, Michigan NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TEACHERS OF MATHEMATICS 1 istory of Algebra in th Scho I urriculum Jeremy Kilpatrick Andrew Izsak flthere is a heaven/or school subjects, algebra H)ill never go there. It is the one subject in the curricuhul1 that has kept children .Ironz finishing high school, /j~onl developing their special interests' and /;~07n enjoying rnuch of their h0711e study work. It has caused 1110re jCllnily ro"Vvs, ,nore tears, 7110re heartaches, and nzore sleeples5' nights than any other school sul~ject. -Anonynlous editorial writer [ca. 1936J N THE United States and Canada before 1700, algebra was absent not only fronl I the school curriculu1l1 but also fro111 the CUITicululll of the early colleges and sCIllinaries. That situation changed during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as colleges and universities across North Anlerica began to offer courses in alge bra. In January 1751, when Benjanlin Franklin's acade111Y was established, the new master Theophilus Grew offered "Writing, Arithnletic, Merchants Accounts, Alge bra, AstTon0111Y, Navigation, and all other branches of Mathenlatics" (Overn 193 p. 373), and "algebra to quadratics" continued to be pali of the freshnlan curricululll after the acaden1Y becanle the University of Pennsylvania in 1779. Algebrcl is first nlentioned as being in the Harvard curriculunl in 1786 but was probably taught 111LlCh earlier, perhaps as early as 1 (Cajori 1890, p. -

The Legacy of New Math on Today's Curricula

The Legacy of New Math on Today’s Curricula Melissa Scranton, Ph.D. Purdue University Global New Math of the 1950s and 60s • CEEB Commission on Mathematics 1959 report • Soviet Launch of Sputnik in 1957 • National Defense Education Act of 1958 • Paradigm Shift in Mathematics Education • New Math focus on Conceptual Understanding of Mathematics rather than Rote Memorization • Discover, Deduction, and Limited Drill What Did New Math Look Like? Bases other than Different Number Sets 10 Representations Reasoning Discovering New Language Solution Before Hidden Patterns Rule Diagrams Properties of Boxes Matrices Arithmetic Frames 1951 1957 & 1958 Max Beberman Edward Begle University of Illinois School Committee on Mathematics School Mathematics Study Group (UICSM) (SMSG) Beberman and Begle promoted a complete conceptual overhaul of math instruction. “Mathematics should be taught as a language, he said. And like language, it should be considered a liberal art, a key to clear thinking, and a logic for solving social as well as scientific problems” (Miller, 1990). “Modern Math” Language Discovery New math quickly won wide acceptance. 50% of all high schools were using New Math as their curriculum by 1965 (Miller, 1990). At its peak, 85% of all elementary and secondary schools had adopted New Math (Miller, 1990). PUBLIC SENTIMENT Image copyright Charles Schulz. Frustration • Ridiculed and deemed a failure by the general public. • Tom Lehrer spoofed with song New Math. • Parents didn’t understand children’s homework. • Teachers not trained on how to implement and instruct the new method. • Implementation inconsistent. What happened to New Math? Where did it go? 40 years later… Enter Common Core 1 National Learning Objectives 2 Adopted by 45 states within a few months. -

New Math” for the 21 Century

”New math” for the 21st century Gunnar Gjone: Some time ago I was listenening to a presentation on the use of internet in education. Concentrating on the internet as a source of information, the presenter stated that it would be important if students could combine search criteria, by the laws of logic, to perform more efficient searches. Perhaps the proponents of the ”new math” had been too early in time for mathematics education? Over the years I had realized that many uses of computers build strongly on logic – forms of programming are obvious examples. Many uses of application programs such as word processors and spreadsheets would also be more efficient by the use of logic. Computers are ”logic machines”, so why not logic in basic mathematics education? The ”new math” revisited The ”new math” movement lasted in most countries from the late 1950s to the early 1970s. In many countries this reform was replaced with stressing the basic skills, i.e.arithmetic/ computation. Also in many countries these changes resulted in strong discussions and heated debates among mathematics educators. The ”new math” movement, however, was not one single reform. It had many different forms, but there was common elements. We can use concepts such as ”structure” and ”logic” to talk about these common elements, but the ”new math” movement was much more. Also it should be noted that many other reforms e.g. individualized math instruction used new math to gain momentum. Some characteristics of the ”new math” movement We will concentrate on two of the characteristics of the movement: the mathematical and the pedagogical. -

Prek12 Math Curriculum Review

PreK12 Math Curriculum Review West St. Paul Mendota Heights Eagan Area Schools School District 197 Prepared by Kate Skappel Curriculum Coordinator Cari Jo Kiffmeyer Director of Curriculum, Instruction and Assessment April 2016 1 Background All students in School District 197 receive instruction in mathematics. Math is one of our four core content areas along with English/Language Arts, Science and Social Studies. The state of Minnesota adopted Math Standards in 2007 with full implementation by the 201011 school year. The standards were set to be reviewed in 201516, During the first special legislative session of 2015, this review was postponed until the 202021 school year. Full implementation of the new math standards will follow the adoption of the new set of standards. The state of Minnesota has not adopted the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics. Consideration will be given during the 202021 review. We determined that, even though the standards were not going to be reviewed at the state level, we would continue as planned with a local math review. Much work has occurred over the past four years with the middle school and high school. We have added math intervention. We then determined a need for a PreK 12 math review for a variety of reasons. Our core resources are over seven years old. Some of our resources are out of print and the online access for our resources has expired and now requires an annual subscription fee. With the addition of 1:1 devices for students in grades three through twelve, we need to assure that our resources are compatible and accessible on these devices. -

The Math Wars California Battles It out Over Mathematics Education Reform (Part II)

comm-calif2.qxp 6/12/97 4:27 PM Page 817 The Math Wars California Battles It Out over Mathematics Education Reform (Part II) Note: The first part of this article appeared in the June/July issue of the Notices, pages 695–702. The Numbers Battle examinations but also group assignments, long- “Show us the data, show us that this program term projects, and portfolios of work done over works,” demands Michael McKeown, the head of a period of time. Some also favor the idea of judg- Mathematically Correct, the San Diego-based ing the efficacy of curricular programs by criteria group critical of mathematics education reform. other than standardized tests, such as the num- McKeown makes his living in the data-driven ber and type of mathematics courses students field of biology, as a researcher at the Salk In- subsequently take. stitute and an adjunct faculty member at UC Such are the views in that portion of the math San Diego. One of the things he finds most vex- wars devoted to testing. The scramble to find ing about the reform is that it has been imple- numbers to support certain viewpoints has led mented without having been subject to large- to some questionable uses of data. For example, scale, well-designed studies to show that student the anti-reform group HOLD (Honest Open Log- achievement rises when the reform materials ical Debate on mathematics reform) recently cir- are used. He points out that what convinced culated an e-mail message containing data on the everyone that there is a problem in mathemat- Elementary Level Mathematics Examination, ics education was low scores on tests like the Na- which is administered in the California State tional Assessment of Educational Progress. -

Calculus Reform--For the Millions

comm-mumford.qxp 3/14/97 10:02 AM Page 559 Calculus Reform— For the Millions David Mumford About twenty years ago I was part of a group of bank, and it is running a special promotion with professors from many fields who met once a a new account which pays imaginary interest at month for dinner and an after-dinner talk given the rate of 100%. The audience immediately sees by one of the members. It was entertaining to that you get imaginary interest building up and hear glimpses of legal issues, historical problems, that the interest on the interest is decreasing discussions of what freedom meant in different your total of real dollars. You run them through cultures. But then I had to give one of these a few more numbers, and they see that their real talks! I was working on algebraic geometry then, funds will go to 0, while their imaginary funds and I tried to figure out what I could say that build up to about 1.i; then they go into real would hold my colleagues’ attention while di- debt, next imaginary debt, and finally get their gesting a large meal. In the end I decided to stick real $1 back, which they immediately withdraw! to a rather anecdotal level but to inject one bit A little picture in the complex plane convinces of real math. I thought I would try to explain to them that this will take 2π years, while after π them the first mathematical formula that I had years they were in debt $1 : voilà, eiπ = 1! seen in school which totally bewildered me. -

Why Do Americans Stink at Math? - Nytimes.Com

12/1/2014 Why Do Americans Stink at Math? - NYTimes.com http://nyti.ms/1nnhIcV MAGAZINE | NYT NOW Why Do Americans Stink at Math? By ELIZABETH GREEN JULY 23, 2014 When Akihiko Takahashi was a junior in college in 1978, he was like most of the other students at his university in suburban Tokyo. He had a vague sense of wanting to accomplish something but no clue what that something should be. But that spring he met a man who would become his mentor, and this relationship set the course of his entire career. Takeshi Matsuyama was an elementary-school teacher, but like a small number of instructors in Japan, he taught not just young children but also college students who wanted to become teachers. At the university-affiliated elementary school where Matsuyama taught, he turned his classroom into a kind of laboratory, concocting and trying out new teaching ideas. When Takahashi met him, Matsuyama was in the middle of his boldest experiment yet — revolutionizing the way students learned math by radically changing the way teachers taught it. Instead of having students memorize and then practice endless lists of equations — which Takahashi remembered from his own days in school — Matsuyama taught his college students to encourage passionate discussions among children so they would come to uncover math’s procedures, properties and proofs for themselves. One day, for example, the young students would derive the formula for finding the area of a rectangle; the next, they would use what they learned to do the same for parallelograms. Taught this new way, math itself seemed transformed. -

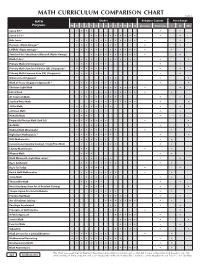

Math Curriculum Comparison Chart

MATH CURRICULUM COMPARISON CHART ©2018 MATH Grades Religious Content Price Range Programs PK K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Christian N/Secular $ $$ $$$ Saxon K-3 * • • • • • • Saxon 3-12 * • • • • • • • • • • • • Bob Jones • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Horizons (Alpha Omega) * • • • • • • • • • • • LIFEPAC (Alpha Omega) * • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Switched-On Schoolhouse/Monarch (Alpha Omega) • • • • • • • • • • • • Math•U•See * • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Primary Math (US) (Singapore) * • • • • • • • • • Primary Math Standards Edition (SE) (Singapore) * • • • • • • • • • Primary Math Common Core (CC) (Singapore) • • • • • • • • Dimensions (Singapore) • • • • • Math in Focus (Singapore Approach) * • • • • • • • • • • • Christian Light Math • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Life of Fred • • • • • • • • • • • • • • A+ Tutorsoft Math • • • • • • • • • • • Starline Press Math • • • • • • • • • • • • ShillerMath • • • • • • • • • • • enVision Math • • • • • • • • • McRuffy Math • • • • • • Purposeful Design Math (2nd Ed.) • • • • • • • • • Go Math • • • • • • • • • Making Math Meaningful • • • • • • • • • • • RightStart Mathematics * • • • • • • • • • • MCP Mathematics • • • • • • • • • Conventional (Spunky Donkey) / Study Time Math • • • • • • • • • • Liberty Mathematics • • • • • Miquon Math • • • • • Math Mammoth (Light Blue series) * • • • • • • • • • Ray's Arithmetic • • • • • • • • • • Ray's for Today • • • • • • • Rod & Staff Mathematics • • • • • • • • • • Jump Math • • • • • • • • • • ThemeVille Math • • • • • • • Beast Academy (from -

Matheompetidcms "

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Augustl Twenty-Three Mathematicians Wm 1998 September SectionAwardsforDistinguished Teaching 1998 By Henry Alder Twenty-three mathematicians won this well as other ways ofsharing the tal Volume 18, Number 6 year's Section Awards for Distinguished ents of these outstanding teachers. Teaching, which were conferred at the Still, there are a few sections that do spring meetings of their sections. The not give awards. The national com latest winners represent the seventh mittee urges these sections to nomi group ofawardees since the inception nate and reward outstanding teach In This Issue of the awards in 1992. ers, and encourages all members of The Committee on the Deborah and the Association to nominate worthy 2 Mathematical Franklin Tepper Haimo Awards for Dis candidates. You may even nominate Breakthrough tinguished College or University Teach someone not in your section by writ ing of Mathematics has nominated at ing to that person's section commit 3 President's most three of these winners for the na tee. tional Deborah and Franklin Tepper The larger the pool of outstanding Repo.-t Haimo Awards. The MAA's Board of nominations, the easier it will be to Governors acted on the nominations at maintain the high standards for sec 4-6 Contributed the summer meeting in Toronto, and tional and national awards. Hope the national award winners will speak Papen fully, this fall every one ofthe MAA's oftheir successes as teachers at the an 29 sections will have a nomination nual meeting in San Antonio in Janu 6 New Math and selection procedure in place.