Sida-Amhara Rural Development Programme 1997–2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

(2) 185-194 Chemical Composition, Mineral Profile and Sensory

East African Journal of Sciences (2019) Volume 13 (2) 185-194 Chemical Composition, Mineral Profile and Sensory Properties of Traditional Cheese Varieties in selected areas of Eastern Gojjam, Ethiopia Mitiku Eshetu1* and Aleme Asresie2 1School of Animal and Range Sciences, Haramaya University, P.O. Box 138, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia 2Department of Animal Production and Technology, Adigrat University, Adigrat, Ethiopia Abstract: This study was conducted to evaluate the chemical composition, mineral profile and sensory properties of Metata, Ayib and Hazo traditional cheese varieties in selected areas of Eastern Gojjam. The chemical composition and mineral content of the cheese varieties were analyzed following standard procedures. Sensory analysis was also conducted by consumer panelists to assess taste, aroma, color, texture and overall acceptability of these traditional cheese varieties. Metata cheese samples had significantly (P<0.05) lower moisture content and higher titratable acidity than Ayib and Hazo cheese samples. The protein, ash, fat contents of Metata cheese samples were significantly (P<0.05) higher than Ayib and Hazo cheese samples. Moreover, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, sodium and potassium contents of Metata cheese samples were significantly (P<0.05) higher than that of Ayib and Hazo cheese samples. Metata cheese samples had also the highest consumer acceptability scores compared to Ayib and Hazo cheese samples. In general, the results of this work showed that Metata cheese has higher nutritional value and overall sensory acceptability. -

Determinants of Rural Household's Livelihood Strategies in Machakel Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Nation Regional State, Ethiopia

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.8, No.10, 2018 Determinants of Rural Household's Livelihood Strategies in Machakel Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Nation Regional State, Ethiopia Adey Belete Department of Disaster Risk Management & Sustainable Development, Institute of Disaster Risk Management & Food Security Studies, Bahir Dar University, P.O.Box 5501 Abstract Rural farm households face an increasing need of looking for alternative income sources to supplement their small scale agricultural activities. However, livelihood strategy is determined by complex and yet empirically untested factors in Machakel Woreda. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the determinants of livelihood strategies in the study area. The data were obtained from 144 sample household heads that were selected through a combination of multi-stage sampling like purposive and simple random sampling techniques. Data were collected through key informant interview, focus group discussion and interview schedule. Multinomial logistic regression model used to analyze determinants of livelihood strategies. Data analysis revealed that farm alone activities has a leading contribution to the total income of sample households (69.8%) followed by non-farm activities (17.2%) and off- farm activities (13 %.). Crop production was the dominant livelihood in the study area and land fragmentation, decline in productivity, occurrence of disaster risk like crop and livestock disease, hail storm, flash flood etc. and market fluctuation were major threatens of livelihood. Four livelihood strategies namely farm alone, farm plus non-farm, farm plus off-farm and farm plus non-farm plus off-farm were identified. Age, education level, sex of household head, marital status, credit access, farm land size, livestock holding size , agro-ecology, family size, frequency of extension contact, distance from market and total net income were major determinants of livelihood strategies in the study area. -

Versus Routine Care on Improving Utilization Of

Andargie et al. Trials (2020) 21:151 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-4002-3 STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access Effectiveness of Checklist-Based Box System Interventions (CBBSI) versus routine care on improving utilization of maternal health services in Northwest Ethiopia: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial Netsanet Belete Andargie1,2* , Mulusew Gerbaba Jebena2 and Gurmesa Tura Debelew2 Abstract Background: Maternal mortality is still high in Ethiopia. Antenatal care, the use of skilled delivery and postnatal care are key maternal health care services that can significantly reduce maternal mortality. However, in low- and middle-income countries, including Ethiopia, utilization of these key services is limited, and preventive, promotive and curative services are not provided as per the recommendations. The aim of this study is to examine the effectiveness of checklist-based box system interventions on improving maternal health service utilization. Methods: A community-level, cluster-randomized controlled trial will be conducted to compare the effectiveness of checklist-based box system interventions over the routine standard of care as a control arm. The intervention will use a health-extension program provided by health extension workers and midwives using a special type of health education scheduling box placed at health posts and a service utilization monitoring box placed at health centers. For this, 1200 pregnant mothers at below 16 weeks of gestation will be recruited from 30 clusters. Suspected pregnant mothers will be identified through a community survey and linked to the nearby health center. With effective communication between health centers and health posts, dropout-tracing mechanisms are implemented to help mothers resume service utilization. -

Protecting Land Tenure Security of Women in Ethiopia: Evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation Program

PROTECTING LAND TENURE SECURITY OF WOMEN IN ETHIOPIA: EVIDENCE FROM THE LAND INVESTMENT FOR TRANSFORMATION PROGRAM Workwoha Mekonen, Ziade Hailu, John Leckie, and Gladys Savolainen Land Investment for Transformation Programme (LIFT) (DAI Global) This research paper was created with funding and technical support of the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights, an initiative of Resource Equity. The Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights is a community of learning and practice that works to increase the quantity and strengthen the quality of research on interventions to advance women’s land and resource rights. Among other things, the Consortium commissions new research that promotes innovations in practice and addresses gaps in evidence on what works to improve women’s land rights. Learn more about the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights by visiting https://consortium.resourceequity.org/ This paper assesses the effectiveness of a specific land tenure intervention to improve the lives of women, by asking new questions of available project data sets. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to investigate threats to women’s land rights and explore the effectiveness of land certification interventions using evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation (LIFT) program in Ethiopia. More specifically, the study aims to provide evidence on the extent that LIFT contributed to women’s tenure security. The research used a mixed method approach that integrated quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative information was analyzed from the profiles of more than seven million parcels to understand how the program had incorporated gender interests into the Second Level Land Certification (SLLC) process. -

Food Insecurity Among Households with and Without Podoconiosis in East and West Gojjam, Ethiopia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Food insecurity among households with and without podoconiosis in East and West Gojjam, Ethiopia Article (Published Version) Ketema, Kassahun, Tsegay, Girmay, Gedle, Dereje, Davey, Gail and Deribe, Kebede (2018) Food insecurity among households with and without podoconiosis in East and West Gojjam, Ethiopia. EC Nutrition, 13 (7). pp. 414-423. ISSN 2453-188X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/76681/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. -

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 and Reassessment of Crop

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 And Reassessment Of Crop Production and Marketing For 2014/15 October 2015 Final Report Ethiopia: Bellmon Analysis - 2014/15 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ iii Table of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Economic Background ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Poverty ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Wage Labor ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 Agriculture Sector Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

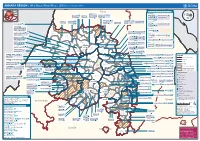

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Farmers' Varietal Selection of Food Barley Genotypes in Gozamin

American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci., 17 (3): 232-238, 2017 ISSN 1818-6769 © IDOSI Publications, 2017 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.aejaes.2017.232.238 Farmers’ Varietal Selection of Food Barley Genotypes in Gozamin District of East Gojjam Zone, Northwestern Ethiopia Yalemtesfa Firew Guade Department of Horticulture, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Debre Markos University, Ethiopia Abstract: In this study, the performance of four improved food barley varieties obtained from Holleta Agricultural Research Center and local variety collected from the study area were evaluated in randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications under farmers’ participatory selection scheme during 2016 main cropping season in Gozamin district, East Gojjam Zone, Northwestern Ethiopia. The objectives of this study were to select adaptable and high yielding food barley genotype(s) using farmers’ preferences and to identify farmers’ preference and selection criteria of the study area. Farmers’ set; grain yield, early maturity, tillering ability and spike length as their selection criteria at maturity stage of the crop. The results of analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated significant differences among genotypes for all traits tested except number of effective tillers and thousand seed weight which were non-significant at 5% probability level. The improved variety EH-1493 (133 days) was the earliest while local variety (142 days) was the latest. The highest mean grain yield was obtained from HB-1307 (3700 kg ha-1 ) and Cross-41/98 (3133 kg ha-1 ) whereas the lowest from the local variety (1693 kg ha 11). Similarly, HB-1307(5033 kg ha ) and Cross-41/98 (3633.33 kg ha 1) had given comparatively the highest above ground biomass yield which was used as a source of feed for animals. -

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire Always 001a. Your name: [NAME] Is this your name? ◯ Yes ◯ No 001b. Enter your name below. 001a = 0 Please record your name 002a = 0 Day: 002b. Record the correct date and time. Month: Year: ◯ TIGRAY ◯ AFAR ◯ AMHARA ◯ OROMIYA ◯ SOMALIE BENISHANGUL GUMZ 003a. Region ◯ ◯ S.N.N.P ◯ GAMBELA ◯ HARARI ◯ ADDIS ABABA ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${this_country} ◯ NORTH WEST TIGRAY ◯ CENTRAL TIGRAY ◯ EASTERN TIGRAY ◯ SOUTHERN TIGRAY ◯ WESTERN TIGRAY ◯ MEKELE TOWN SPECIAL ◯ ZONE 1 ◯ ZONE 2 ◯ ZONE 3 ZONE 5 003b. Zone ◯ ◯ NORTH GONDAR ◯ SOUTH GONDAR ◯ NORTH WELLO ◯ SOUTH WELLO ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST GOJAM ◯ WEST GOJAM ◯ WAG HIMRA ◯ AWI ◯ OROMIYA 1 ◯ BAHIR DAR SPECIAL ◯ WEST WELLEGA ◯ EAST WELLEGA ◯ ILU ABA BORA ◯ JIMMA ◯ WEST SHEWA ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST SHEWA ◯ ARSI ◯ WEST HARARGE ◯ EAST HARARGE ◯ BALE ◯ SOUTH WEST SHEWA ◯ GUJI ◯ ADAMA SPECIAL ◯ WEST ARSI ◯ KELEM WELLEGA ◯ HORO GUDRU WELLEGA ◯ Shinile ◯ Jijiga ◯ Liben ◯ METEKEL ◯ ASOSA ◯ PAWE SPECIAL ◯ GURAGE ◯ HADIYA ◯ KEMBATA TIBARO ◯ SIDAMA ◯ GEDEO ◯ WOLAYITA ◯ SOUTH OMO ◯ SHEKA ◯ KEFA ◯ GAMO GOFA ◯ BENCH MAJI ◯ AMARO SPECIAL ◯ DAWURO ◯ SILTIE ◯ ALABA SPECIAL ◯ HAWASSA CITY ADMINISTRATION ◯ AGNEWAK ◯ MEJENGER ◯ HARARI ◯ AKAKI KALITY ◯ NEFAS SILK-LAFTO ◯ KOLFE KERANIYO 2 ◯ GULELE ◯ LIDETA ◯ KIRKOS-SUB CITY ◯ ARADA ◯ ADDIS KETEMA ◯ YEKA ◯ BOLE ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${level1} ◯ TAHTAY ADIYABO ◯ MEDEBAY ZANA ◯ TSELEMTI ◯ SHIRE ENIDASILASE/TOWN/ ◯ AHIFEROM ◯ ADWA ◯ TAHTAY MAYCHEW ◯ NADER ADET ◯ DEGUA TEMBEN ◯ ABIYI ADI/TOWN/ ◯ ADWA/TOWN/ ◯ AXUM/TOWN/ ◯ SAESI TSADAMBA ◯ KLITE -

Farmers Willingness to Participate in Voluntary Land Consolidation in Gozamin District, Ethiopia

land Article Farmers Willingness to Participate In Voluntary Land Consolidation in Gozamin District, Ethiopia Abebaw Andarge Gedefaw 1,2,* , Clement Atzberger 1 , Walter Seher 3 and Reinfried Mansberger 1 1 Institute of Surveying, Remote Sensing and Land Information, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Peter-Jordan-Strasse 82, 1190 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (C.A.); [email protected] (R.M.) 2 Institute of Land Administration, Debre Markos University, 269 Debre Markos, Ethiopia 3 Institute of Spatial Planning, Environmental Planning and Land Rearrangement, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Peter-Jordan-Strasse 82, 1190 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 10 September 2019; Accepted: 10 October 2019; Published: 12 October 2019 Abstract: In many African countries and especially in the highlands of Ethiopia—the investigation site of this paper—agricultural land is highly fragmented. Small and scattered parcels impede a necessary increase in agricultural efficiency. Land consolidation is a proper tool to solve inefficiencies in agricultural production, as it enables consolidating plots based on the consent of landholders. Its major benefits are that individual farms get larger, more compact, contiguous parcels, resulting in lower cultivation efforts. This paper investigates the determinants influencing the willingness of landholder farmers to participate in voluntary land consolidation processes. The study was conducted in Gozamin District, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. The study was mainly based on survey data collected from 343 randomly selected landholder farmers. In addition, structured interviews and focus group discussions with farmers were held. The collected data were analyzed quantitatively mainly by using a logistic regression model and qualitatively by using focus group discussions and expert panels. -

Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies The

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES THE PREVALENCE OF SYMPTOMATIC AND ASYMPTOMATIC MALARIA AND ITS ASSOCIATED FACTORS IN DEBRE ELIAS DISTRICT COMMUNITIES, NORTHWEST ETHIOPIA BY ABTIE ABEBAW (BSc) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES, ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MEDICAL PARASITOLOGY FEBRUARY, 2019 ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF MEDICAL MICROBIOLOGY, IMMUNOLOGY AND PARASITOLOGY The prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic malaria and its associated factors in Debre Elias district communities, Northwest Ethiopia By Abtie Abebaw (BSc), AAU Advisors: Prof. Asrat Hailu, AAU Dr. Tadesse Kebede, AAU ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES The Prevalence of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Malaria and Its Associated Factors in Debre Elias District Communities, Northwest Ethiopia By Abtie Abebaw A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Medical Parasitology Approved by Examining Board: Prof. Asrat Hailu, AAU Signature __________Date__/___/____ Advisor Dr. Tadesse Kebede, AAU Signature __________Date___/___/___ Advisor Mr. Muluneh Ademe (MSc) Signature __________Date__/___/____ Examiner Dr. Solomon Gebre-Selassie Signature __________Date___/___/___ Examiner Dr. Tamrat Abebe Signature __________Date___/___/___ Chairperson i Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude and heartfelt thanks to my advisors Dr. Tadesse Kebede and Prof. Asrat Hailu for their continuous support and guidance in the development of this thesis. I am grateful to the digital library, computer center and library staffs for their overall support and cooperation.