Responses of Woodpeckers to Selective Logging and Forest Fragmentation in Kalimantan – Preliminary Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-Eaters, Babblers, and a Whole Lot More

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-eaters, Babblers, and a whole lot more A Tropical Birding Set Departure July 1-16, 2018 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos by Ken Behrens TOUR SUMMARY Borneo lies in one of the biologically richest areas on Earth – the Asian equivalent of Costa Rica or Ecuador. It holds many widespread Asian birds, plus a diverse set of birds that are restricted to the Sunda region (southern Thailand, peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo), and dozens of its own endemic birds and mammals. For family listing birders, the Bornean Bristlehead, which makes up its own family, and is endemic to the island, is the top target. For most other visitors, Orangutan, the only great ape found in Asia, is the creature that they most want to see. But those two species just hint at the wonders held by this mysterious island, which is rich in bulbuls, babblers, treeshrews, squirrels, kingfishers, hornbills, pittas, and much more. Although there has been rampant environmental destruction on Borneo, mainly due to the creation of oil palm plantations, there are still extensive forested areas left, and the Malaysian state of Sabah, at the northern end of the island, seems to be trying hard to preserve its biological heritage. Ecotourism is a big part of this conservation effort, and Sabah has developed an excellent tourist infrastructure, with comfortable lodges, efficient transport companies, many protected areas, and decent roads and airports. So with good infrastructure, and remarkable biological diversity, including many marquee species like Orangutan, several pittas and a whole Borneo: Bristleheads and Broadbills July 1-16, 2018 range of hornbills, Sabah stands out as one of the most attractive destinations on Earth for a travelling birder or naturalist. -

Assessment and Conservation of Threatened Bird Species at Laojunshan, Sichuan, China

CLP Report Assessment and conservation of threatened bird species at Laojunshan, Sichuan, China Submitted by Jie Wang Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, P.R.China E-mail:[email protected] To Conservation Leadership Programme, UK Contents 1. Summary 2. Study area 3. Avian fauna and conservation status of threatened bird species 4. Habitat analysis 5. Ecological assessment and community education 6. Outputs 7. Main references 8. Acknowledgements 1. Summary Laojunshan Nature Reserve is located at Yibin city, Sichuan province, south China. It belongs to eastern part of Liangshan mountains and is among the twenty-five hotspots of global biodiversity conservation. The local virgin alpine subtropical deciduous forests are abundant, which are actually rare at the same latitudes and harbor a tremendous diversity of plant and animal species. It is listed as a Global 200 ecoregion (WWF), an Important Bird Area (No. CN205), and an Endemic Bird Area (No. D14) (Stattersfield, et al . 1998). However, as a nature reserve newly built in 1999, it is only county-level and has no financial support from the central government. Especially, it is quite lack of scientific research, for example, the avifauna still remains unexplored except for some observations from bird watchers. Furthermore, the local community is extremely poor and facing modern development pressures, unmanaged human activities might seriously disturb the local ecosystem. We conducted our project from April to June 2007, funded by Conservation Leadership Programme. Two fieldwork strategies were used: “En bloc-Assessment” to produce an avifauna census and ecological assessments; "Special Survey" to assess the conservation status of some threatened endemic bird species. -

Anatomical Evidence for Phylogenetic Relationships Among Woodpeckers

ANATOMICAL EVIDENCE FOR PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS AMONG WOODPECKERS WILLIAM R. GOODGE ALT•tOUCr•the functionalanatomy of woodpeckershas long been a subjectof interest,their internal anatomyhas not been usedextensively for determiningprobable phylogeneticrelationships within the family. In part this is probablydue to the reluctanceto use highly adaptivefea- tures in phylogeneticstudies becauseof the likelihood of convergent evolution. Bock (1967) and othershave pointedout that adaptivehess in itself doesnot rule out taxonomicusefulness, and that the highly adaptivefeatures will probablybe the oneshaving conspicuous anatomical modifications,and Bock emphasizesthe need for detailedstudies of func- tion beforeusing featuresin studiesof phylogeny.Although valuable, functionalconclusions are often basedon inferencesnot backed up by experimentaldata. As any similaritybetween species is possiblydue to functionalconvergence, I believewhat is neededmost is detailedstudy of a numberof featuresin order to distinguishbetween similarities re- sultingfrom convergenceand thosebased on phylogenticrelationship. Simplestructures are not necessarilymore primitive and morphological trendsare reversible,as Mayr (1955) has pointedout. Individual varia- tion may occur and various investigatorsmay interpret structuresdif- ferently. Despite these limitations,speculation concerning phylogeny will continuein the future,and I believethat it shouldbe basedon more, rather than fewer anatomical studies. MATERIALS AND METItODS Alcoholic specimensrepresenting 33 genera -

Prairie Falcon Northern Flint Hills Audubon Society Newsletter

“The World’s Worst Problems” Dr. Walter Dodds TUESDAY, Nov. 16, 7 p.m. manhattan Public Library Groesbeck Meeting Room, 2nd floor Dr. Dodds will explore some of the worst problems that currently, or could be predicted to, afflict humanity. The root causes and required solutions will also be addressed in a general sense for all the major problems. The presentation will build on “Humanity’s Footprint,” a recent book on global environmental issues by Dr. Dodds. The talk will bring out points based on sound scientific facts, and issues that humanity should not ignore if they are to at least sustain current lifestyles, and certainly if we are to improve living conditions for all people. Dr. Dodds is a University Distinguished Professor in Biology at Kansas State University. prairie falcon Northern Flint Hills Audubon Society Newsletter Vol. 39, No. 3 ~ November 2010 Northern Flint Hills Audubon Society, Northern Flint Hills Audubon Society, 1932, Manhattan, KS 66505-1932 Box P.O. Inside Upcoming Events: pg. 2 - Skylight plus Nov. 1 - Board Meeting 6 p.m. Home of Tom and MJ Morgan pete cohen Nov. 13 - BirdSeed PICKUP UFM parking lot, pg. 3 - Life After Death 8:30-11:30 a.m. dru clarke Nov. 13 - 8 a.m. - noon: Sat. Birding - Cleanup at Michel-Ross Preserve - Bring a bag pg. 4 - K-State Freshmen respond to & binoculars (STAGG HILL) Ghost Bird documentary Nov. 16- Program by Walter Dodds, 7 p.m. TUESDAY, MJ morgan Manhattan Public Library Groesbeck meeting rm pg. 5 - Take Note Dec. 6 - Board Meeting Dec. 18 - Manhattan Christmas Bird Count Printed by Claflin Books & Copies Manhattan, KS Skylight plus Pete Cohen The sky looked everyone else need to keep making. -

Woodpeckers and Allies)

Coexistence, Ecomorphology, and Diversification in the Avian Family Picidae (Woodpeckers and Allies) A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Matthew Dufort IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY F. Keith Barker and Kenneth Kozak October 2015 © Matthew Dufort 2015 Acknowledgements I thank the many people, named and unnamed, who helped to make this possible. Keith Barker and Ken Kozak provided guidance throughout this process, engaged in innumerable conversations during the development and execution of this project, and provided invaluable feedback on this dissertation. My committee members, Jeannine Cavender-Bares and George Weiblen, provided helpful input on my project and feedback on this dissertation. I thank the Barker, Kozak, Jansa, and Zink labs and the Systematics Discussion Group for stimulating discussions that helped to shape the ideas presented here, and for insight on data collection and analytical approaches. Hernán Vázquez-Miranda was a constant source of information on lab techniques and phylogenetic methods, shared unpublished PCR primers and DNA extracts, and shared my enthusiasm for woodpeckers. Laura Garbe assisted with DNA sequencing. A number of organizations provided financial or logistical support without which this dissertation would not have been possible. I received fellowships from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program and the Graduate School Fellowship of the University of Minnesota. Research funding was provided by the Dayton Fund of the Bell Museum of Natural History, the Chapman Fund of the American Museum of Natural History, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the University of Minnesota Council of Graduate Students. -

The Current Status of Sinaloa Martin Progne Sinaloae

Cotinga 32 The current status of Sinaloa Martin Progne sinaloae Nicholas A. Lethaby and Jon R. King Received 24 February 2009; final revision accepted 13 November 2009 first published online 16 March 2010 Cotinga 32 (2010): 90–95 La Golondrina de Sinaloa Progne sinaloae es una especie categorizada como Datos Deficientes y endémica reproductiva de la Sierra Madre Occidental y las montañas Volcánicas Centrales de México. Sus áreas de invernada son desconocidas. A pesar de que su estado es descrito como poco común a relativamente común, no hay localidades donde la especie sea vista regularmente o en números significativos. Históricamente, los registros han sido de colonias reproductivas de 15–30 aves o más; pero los registros acumulados por los autores a lo largo de las últimas dos décadas han sido en su mayoría de migrantes en las tierras bajas, sin registros reproductivos definitivos excepto por una colonia recientemente descubierta de solo 2–6 individuos en Sinaloa. La Golondrina de Sinaloa es inherentemente conspicua y los machos son fáciles de identificar, por lo que es una especie difícil de pasar desapercibida. Parece ser poco común y altamente local en el mejor de los casos, y posiblemente muy rara. Monitoreos formales deberían ser desarrollados para evaluar con precisión el actual estado de conservación de la especie y sus tendencias poblacionales. The Sierra Madre Occidental is an extensive There are potentially several reasons why mountain range in north-west Mexico. Although the apparent rarity of Sinaloa Martin has gone much of the sierra appears to be extremely remote, unnoticed. subsistence farming, ranching, hunting and logging 1. -

Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Chapter 92A)

1 S 23/2005 First published in the Government Gazette, Electronic Edition, on 11th January 2005 at 5:00 pm. NO.S 23 ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (CHAPTER 92A) ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (AMENDMENT OF FIRST, SECOND AND THIRD SCHEDULES) NOTIFICATION 2005 In exercise of the powers conferred by section 23 of the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act, the Minister for National Development hereby makes the following Notification: Citation and commencement 1. This Notification may be cited as the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Amendment of First, Second and Third Schedules) Notification 2005 and shall come into operation on 12th January 2005. Deletion and substitution of First, Second and Third Schedules 2. The First, Second and Third Schedules to the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act are deleted and the following Schedules substituted therefor: ‘‘FIRST SCHEDULE S 23/2005 Section 2 (1) SCHEDULED ANIMALS PART I SPECIES LISTED IN APPENDIX I AND II OF CITES In this Schedule, species of an order, family, sub-family or genus means all the species of that order, family, sub-family or genus. First column Second column Third column Common name for information only CHORDATA MAMMALIA MONOTREMATA 2 Tachyglossidae Zaglossus spp. New Guinea Long-nosed Spiny Anteaters DASYUROMORPHIA Dasyuridae Sminthopsis longicaudata Long-tailed Dunnart or Long-tailed Sminthopsis Sminthopsis psammophila Sandhill Dunnart or Sandhill Sminthopsis Thylacinidae Thylacinus cynocephalus Thylacine or Tasmanian Wolf PERAMELEMORPHIA -

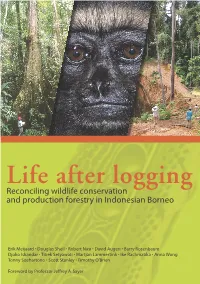

Life After Logging: Reconciling Wildlife Conservation and Production Forestry in Indonesian Borneo

Life after logging Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Erik Meijaard • Douglas Sheil • Robert Nasi • David Augeri • Barry Rosenbaum Djoko Iskandar • Titiek Setyawati • Martjan Lammertink • Ike Rachmatika • Anna Wong Tonny Soehartono • Scott Stanley • Timothy O’Brien Foreword by Professor Jeffrey A. Sayer Life after logging: Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Life after logging: Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Erik Meijaard Douglas Sheil Robert Nasi David Augeri Barry Rosenbaum Djoko Iskandar Titiek Setyawati Martjan Lammertink Ike Rachmatika Anna Wong Tonny Soehartono Scott Stanley Timothy O’Brien With further contributions from Robert Inger, Muchamad Indrawan, Kuswata Kartawinata, Bas van Balen, Gabriella Fredriksson, Rona Dennis, Stephan Wulffraat, Will Duckworth and Tigga Kingston © 2005 by CIFOR and UNESCO All rights reserved. Published in 2005 Printed in Indonesia Printer, Jakarta Design and layout by Catur Wahyu and Gideon Suharyanto Cover photos (from left to right): Large mature trees found in primary forest provide various key habitat functions important for wildlife. (Photo by Herwasono Soedjito) An orphaned Bornean Gibbon (Hylobates muelleri), one of the victims of poor-logging and illegal hunting. (Photo by Kimabajo) Roads lead to various impacts such as the fragmentation of forest cover and the siltation of stream— other impacts are associated with improved accessibility for people. (Photo by Douglas Sheil) This book has been published with fi nancial support from UNESCO, ITTO, and SwedBio. The authors are responsible for the choice and presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of CIFOR, UNESCO, ITTO, and SwedBio and do not commit these organisations. -

A Short Survey of the Meratus Mountains, South Kalimantan Province, Indonesia: Two Undescribed Avian Species Discovered

BirdingASIA 26 (2016): 107–113 107 LITTLEKNOWN AREA A short survey of the Meratus Mountains, South Kalimantan province, Indonesia: two undescribed avian species discovered J. A. EATON, S. L. MITCHELL, C. NAVARIO GONZALEZ BOCOS & F. E. RHEINDT Introduction of the montane part of Indonesia’s Kalimantan The avian biodiversity and endemism of Borneo provinces has seldom been visited (Brickle et al. is impressive, with some 50 endemic species 2009). One of the least-known areas and probably described from the island under earlier taxonomic the most isolated mountain range (Davison 1997) arrangements (e.g. Myers 2009), and up to twice are the Meratus Mountains, South Kalimantan as many under the recently proposed taxonomic province (Plates 1 & 2), a 140 km long north–south arrangements of Eaton et al. (2016). Many of arc of uplands clothed with about 2,460 km² of these are montane specialists, with around 27 submontane and montane forest, rising to the species endemic to Borneo’s highlands. Although 1,892 m summit of Gn Besar (several other peaks the mountains of the Malaysian states, Sabah exceed 1,600 m). Today, much of the range is and Sarawak, are relatively well-explored, much unprotected except for parts of the southern Plates 1 & 2. Views across the Meratus Mountain range, South Kalimantan province, Kalimantan, Indonesia, showing extensive forest cover, July 2016. CARLOS NAVARIO BOCOS CARLOS NAVARIO BOCOS 108 A short survey of the Meratus Mountains, South Kalimantan, Indonesia: two undescribed avian species discovered end that lie in the Pleihari Martapura Wildlife (2.718°S 115.599°E). Some surveys were curtailed Reserve (Holmes & Burton 1987). -

No. 407/2009 Amending Council Regulation (EC)

19.5.2009 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 123/3 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 407/2009 of 14 May 2009 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Bolitoglossa dofleini, Cynops ensicauda, Echinotriton andersoni, Pachytriton labiatus, Paramesotriton spp., Sala mandra algira and Tylototriton spp. – which are currently not listed in the Annex to Regulation (EC) No 338/97 – Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European are being imported into the Community in such numbers Community, as to warrant monitoring. Those species should therefore be included in Annex D to the Annex to Regulation (EC) No 338/97. Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein ( 1), and in particular Article 19(3) thereof, (5) At the 14th Conference of the Parties to CITES in June 2007 new nomenclatural references for animals were adopted. Some inconsistencies between the CITES Appendices and the scientific names in those nomen clatural references as regards the species Asarcornis Whereas: scutulata and Pezoporus occidentalis, the families Rheobatra chidae and Phasianidae as well as the order Scandentia were discovered. Since those inconsistencies also appear in the Annex to Regulation (EC) No 338/97, it should be (1) Regulation (EC) No 338/97 lists animal and plant species adapted accordingly. in respect of which trade is restricted or controlled. Those lists incorporate the lists set out in the Appendices to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, hereinafter ‘the CITES Convention’. -

Recovery Plan for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker (Campephilus Principalis)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Recovery Plan for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) I Recovery Plan for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) April, 2010 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Approved: Regional Director, Southeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: II Disclaimer Notice of Copyrighted Material Cover Illustration Credit: Recovery Plans delineate Permission to use copyrighted A male Ivory-billed Woodpecker reasonable actions that are illustrations and images in the at a nest hole. (Photo by Arthur believed to be required to final version of this recovery plan Allen, 1935/Copyright Cornell recover and/or protect listed has been granted by the copyright Lab of Ornithology.) species. Plans published by holders. These illustrations the U.S. Fish and Wildlife are not placed in the public Service (Service) are sometimes domain by their appearance prepared with the assistance herein. They cannot be copied or of recovery teams, contractors, otherwise reproduced, except in state agencies, and other affected their printed context within this and interested parties. Plans document, without the consent of are reviewed by the public and the copyright holder. submitted for additional peer review before the Service adopts Literature Citation Should Read them. Objectives will be attained as Follows: and any necessary funds made U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. available subject to budgetary 200x. Recovery Plan for the and other constraints affecting Ivory-billed Woodpecker the parties involved, as well as the (Campephilus principalis). need to address other priorities. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Recovery plans do not obligate Atlanta, Georgia. -

Abstracts of Those Ar- Dana L Moseley Ticles Using Packages Tm and Topicmodels in R to Ex- Graham E Derryberry Tract Common Words and Trends

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed alphabetically by last name of presenting author Oral Presentations . 2 Lightning Talks . 161 Posters . 166 AOS 2018 Meeting 9-14 April 2018 ORAL PRESENTATIONS Combining citizen science with targeted monitoring we argue how the framework allows for effective large- for Gulf of Mexico tidal marsh birds scale inference and integration of multiple monitoring efforts. Scientists and decision-makers are interested Evan M Adams in a range of outcomes at the regional scale, includ- Mark S Woodrey ing estimates of population size and population trend Scott A Rush to answering questions about how management actions Robert J Cooper or ecological questions influence bird populations. The SDM framework supports these inferences in several In 2010, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill affected many ways by: (1) monitoring projects with synergistic ac- marsh birds in the Gulf of Mexico; yet, a lack of prior tivities ranging from using approved standardized pro- monitoring data made assessing impacts to these the tocols, flexible data sharing policies, and leveraging population impacts difficult. As a result, the Gulf of multiple project partners; (2) rigorous data collection Mexico Avian Monitoring Network (GoMAMN) was that make it possible to integrate multiple monitoring established, with one of its objectives being to max- projects; and (3) monitoring efforts that cover multiple imize the value of avian monitoring projects across priorities such that projects designed for status assess- the region. However, large scale assessments of these ment can also be useful for learning or describing re- species are often limited, tidal marsh habitat in this re- sponses to management activities.