Nigeria: COI Compilation on Human Trafficking December 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Debasish Bandyopadhyay: Curriculum Vitae Debasish Bandyopadhyay, MSc, PhD, MRSC E - mail : [email protected] Assistant Professor Phone: 956-665-3824 Department of Chemistry (ESCNE 3.492) The University of Texas-Rio Grande Valley (E-mail is Preferred) 1201, West University Drive Prepared on September 11, 2019 Edinburg; TX 78539 Objective Contribute to research and teaching in Chemistry and make a visible difference to the quality of human life associated with Food, Nutrition, and Medicine. Specific areas of interest include Food Chemistry, Natural Product Chemistry, Organic/Medicinal Chemistry, and Green chemistry. Specific Aims ➢ To develop outstanding students for the advancement of the society. ➢ To identify new and novel nutritious food sources ➢ To develop effective drugs for the benefit of mankind. Highlights Academic qualification: M. Sc. (1st Class), B. Ed. (1st Class), Ph. D. Teaching experience in the United States: 9+ years Publications in internationally peer-reviewed journals: 74 (another 5 are in pipeline). Publications in internationally peer-reviewed journals as corresponding author: 16 (another 5 are in pipeline) Plenary/Keynote/Invited (International) Lectures: 7 International/National presentations: 93 State/Regional/Local presentations: 93 Book Chapters: 6 Book (Edited): 1 Press Releases: 3 [Covered by more than 240 news agencies worldwide] External Grant Awarded: US $417,329.00 [Role: Principal Investigator] Internal Competitive Research Grants Awarded as PI: US $9,100.00 American Chemical Society DOC Travel Award: US $1,200.00 [Fall 2012 & Fall 2017] Editorial Board Member: 7 International Journals. Associate Editor: 1 International Journals Reviewer: 46 International Journals Teaching Evaluation Average teaching evaluation (excellent/good) since Fall 2010 to Summer II, 2019 is as follows: Overall: 97.15% Excellent/Good (Lecture: 95.37%; Lab: 96.60%; Research: 99.50%) Research Foci (1) Identification of new and novel nutritious food sources and chemical analysis of fruits, vegetables, and food waste. -

Online Journalism and the Challenge of Ethics in Nigeria

Journalism and Mass Communication, October 2016, Vol. 6, No. 10, 585-593 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2016.10.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Online Journalism and the Challenge of Ethics in Nigeria Chike Walter Duru Justice For All/British Council, Abuja, Nigeria Online journalism has changed the face of journalism practice in Nigeria and the world at large. The Internet has virtually revolutionized the process of news and information gathering and dissemination. However, not abiding by the ethics of the profession has become its major burden, a situation that is blamed on certain identified factors. Presently, there is no clear distinction between the role of conventional journalism and citizen journalism. Conventional journalism, which is the mainstream profession of journalism, requires one form of training or the other, either through education or on the job training, for them to discharge their social responsibility role, unlike in the case of citizen journalism, which is presently usurping the role of conventional journalism. This development spells negative effects to the trend of journalism. No doubt, the Internet has removed the barriers of space and time on human interactions; hence, information can easily be obtained at a relatively low cost; but, the major challenges are those of ethics, professionalism, and training. These issues need to be addressed urgently before they set the country on fire. This article traces the background of the ethical challenge and examines its management, highlighting the steps that could be taken to tackle the menace. The reasons for the continued growth in audience of new news site are also explained. Keywords: online journalism, citizen journalism, conventional journalism, ethics, social responsibility Introduction The advent of online media across the globe is a historic revolution that has changed the fortunes of journalism practice and shaped the profession in a symbolic form. -

Oko Haram Leader Claim Re Pon I Ilit for Killing Kaduna Cleric Heik Al

5/21/2019 Boko Haram Leader Claims Responsibility For Killing Kaduna Cleric Sheik Albani , Threatens To Attack Refineries In The Niger Delta | Sahara Report… oko Haram Leader Claim Reponiilit For Killing Kaduna Cleric heik Alani , Threaten To Attack Refinerie In The Niger Delta arel a month after a repected cleric heik Auwal Alani wa killed in Zaria Kaduna tate the leaderhip of oko Haram under Auakar hekau eterda releaed a new video claiming the ect carried out the aaination of heik Alani. Y AHARARPORTR, NW YORK F 20, 2014 saharareporters.com/2014/02/20/boko-haram-leader-claims-responsibility-killing-kaduna-cleric-sheik-albani-threatens 1/23 5/21/2019 Boko Haram Leader Claims Responsibility For Killing Kaduna Cleric Sheik Albani , Threatens To Attack Refineries In The Niger Delta | Sahara Report… saharareporters.com/2014/02/20/boko-haram-leader-claims-responsibility-killing-kaduna-cleric-sheik-albani-threatens 2/23 5/21/2019 Boko Haram Leader Claims Responsibility For Killing Kaduna Cleric Sheik Albani , Threatens To Attack Refineries In The Niger Delta | Sahara Report… Sponsored Ad Interested in Advertising? OURC: AHARARPORTR, NW YORK RAD MOR: NW YOU MAY ALO LIK The 7 Wort Food For Your rain You Need To top ating Organic Welcome New WiFi ooter Ha Internet Provider Running cared in Vietnam WiFi uperooter 11 Cancer mptom You Are Proal Ignoring ta Fit, ta Active saharareporters.com/2014/02/20/boko-haram-leader-claims-responsibility-killing-kaduna-cleric-sheik-albani-threatens 3/23 5/21/2019 Boko Haram Leader Claims Responsibility For Killing -

African Political Economy Chris Allen and Jan Burgess (ROAPE) Is Published Quarterly by Carfax Publishing Company for the ROAPE International Collective

AfricaREVIEW OFn Political Economy EDITORS: The Review of African Political Economy Chris Allen and Jan Burgess (ROAPE) is published quarterly by Carfax Publishing Company for the ROAPE international collective. Now 24 years old, BOOK REVIEWS: ROAPE is a fully refereed journal covering all Ray Bush, Roy Love and Morris Szeftel aspects of African political economy. ROAPE has always involved the readership in shaping EDITORIAL WORKING GROUP: the journal's coverage, welcoming Chris Allen, Carolyn Baylies, Lyn Brydon, contributions from grass roots organisations, Janet Bujra, Jan Burgess, Ray Bush, Carolyne women's organisations, trade unions and Dennis, Anita Franklin, Jon Knox, Roy Love, political groups. The journal is unique in the Giles Mohan, Colin Murray, Mike Powell, comprehensiveness of its bibliographic Stephen Riley, David Seddon, David Simon, referencing, information monitoring, Colin Stoneman, Morris Szeftel, Tina statistical documentation and coverage of Wallace, Gavin Williams, A. B. Zack- work-in-progress. Williams Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for submission, should be sent CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: to Jan Burgess, ROAPE Publications Ltd, Africa: Rok Ajulu (Grahamstown), P.O. Box 678, Sheffield SI 1BF, UK. Yusuf Bangura (Zaria), Billy Cobbett Tel: 44 +(0)1226 +74.16.60; Fax 44 +(0)1226 (Johannesburg), Antonieta Coelho (Luanda), +74.16.61; [email protected]. Bill Freund (Durban), Jibril Ibrahim (Zaria), Amadina Lihamba (Dar es Salaam), Business correspondence, including orders Mahmood Mamdani (Cape Town), Trevor and remittances relating to subscriptions, Parfitt (Cairo), Lloyd Sachikonye (Harare), back numbers and offprints, should be Carol Thompson (Arizona); Canada: addressed to the publisher: Carfax Publishing, Jonathan Barker (Toronto), Bonnie Campbell Taylor & Francis Ltd, Customer Services (Montreal), Dixon Eyoh (Toronto), John Department, Rankine Road, Basingstoke, Loxley (Winnipeg), John Saul (Toronto); Hants RG24 8PR, UK. -

The Strategic Dimension of Chinese Engagement with Latin America

ISSN 2330-9296 Perry Paper Series, no. 1 The Strategic Dimension of Chinese Engagement with Latin America R. Evan Ellis William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies 2013 The opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of Dr. William J. Perry, the Perry Center, or the US Depart- ment of Defense. Book Design: Patricia Kehoe Cover Design: Vitmary (Vivian) Rodriguez CONTENTS FOREWORD V PREFACE VII CHAPTER ONE Introduction 1 CHAPTER TWO The Impact of China on the Region 11 CHAPTER THREE The Question of Chinese Soft Power 33 CHAPTER FOUR Chinese Commercial Activities in Strategic Sectors 51 CHAPTER FIVE The PRC–Latin America Military Relationship 85 CHAPTER SIX China–Latin America Organized Crime Ties 117 CHAPTER SEVEN A “Strategic Triangle” between the PRC, the US, and Latin America? 135 CHAPTER EIGHT The Way Forward 153 FOREWORD With the publication of this volume, the William J. Perry Center for Hemi- spheric Defense Studies presents the first of the Perry Papers, a series of stim- ulating thought pieces on timely security and defense topics of global propor- tions from a regional perspective. The Perry Papers honor the 19th Secretary of Defense, Dr. William J. Perry, whose vision serves as the foundation for the first three of the five current regional security studies centers. Dr. Perry has espoused the belief that education “provides the basis for partner nations’ establishing and building enhanced relations based on mutual re- spect and understanding, leading to confidence, collaboration, and cooperation.” The faculty and staff of the Perry Center believe strongly in the same princi- ples. -

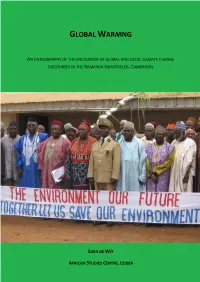

Global Warning

GLOBAL WARNING AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE ENCOUNTER OF GLOBAL AND LOCAL CLIMATE CHANGE DISCOURSES IN THE BAMENDA GRASSFIELDS, CAMEROON SARA DE WIT AFRICAN STUDIES CENTRE, LEIDEN Research Master Thesis in African Studies African Studies Centre (ASC), Leiden University February 2011 “Global Warning” Sara de Wit ([email protected]) Supervisors Prof. dr. Mirjam de Bruijn Prof. dr. Wouter van Beek i For my father, brother and sister Sharing in your love is a wonderful experience ii Table of contents CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 1.1 What this thesis is about, problem statement, chapter outline………………………………………………………….…1 CHAPTER TWO: Theoretical and methodological considerations 2.1 The scope of study: from Kyoto to the Bamenda Grassfields and back to Copenhagen………………………17 2.2 Travelling discourses: Studying global and local connectivity……………………………………………………………..20 2.3 Social constructivism as an alternative ‘lens’……………………………………………………………………………………..27 2.3.1 Media(ted) discourses of science and politics…………………………………………………………………….30 2.3.2 Science and its struggle for ‘truth’………………………………………………………………………………………33 2.4 The power of discourses, or discourses as power………………………………………………………………………………37 2.4.1 Foucault’s notion of power/knowledge……………………………………………………………………………...40 CHAPTER THREE: Talking climate change into existence – The role of NGOs in disseminating the green message 3.1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….42 3.2 The modern environmental era: The social construction of climate change in historical perspective…48 3.2.1 Poetic -

The Role of the Beijing Olympics in China's Public Diplomacy

THE ROLE OF THE BEIJING OLYMPICS IN CHINA’S PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND ITS IMPACT ON POLITICS, ECONOMICS AND ENVIRONMENT Evans Phidelis Aryabaha A dissertation presented to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Malta for the degree of Master in Contemporary Diplomacy June 2010 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation is my own original work. Evans Phidelis Aryabaha 6 June 2010, Beijing, China ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With deep gratitude, I express my sincere appreciation to Ambassador Kishan S. Rana, Ms. Hannah Slavik and all Diplo Staff for their continuous support, patient guidance and invaluable insights throughout this course. My appreciation also goes to my colleague Mr. Michael Bulwaka for his inspiration and encouragement, and for sharing information about Diplo offers; and to Diplo Foundation for its partial sponsorship. I salute the Administration of the Foreign Ministry in Kampala and the Uganda Embassy in Beijing for granting me a study opportunity for career advancement, knowledge expansion and skills enhancement in Contemporary Diplomacy. Finally, I am greatly indebted to my dear wife Caroline Ngabirano Aryabaha for her love and support, thoughtfulness and understanding especially during the course of this study. iii DEDICATION To my precious trio; Ayesiga Alvin, Ashaba Anita and Aheebwa Alton, for their delightful compliments, fascinating curiosity and inspiration to greater heights. iv ABSTRACT The 2008 Beijing Olympics were ardently sought, lavishly staged and hugely successful, despite intense scrutiny, speculation and setbacks. Amplified by modern media, most controversies revolved around China‟s political repression, epitomised by Tibet brutality. Resultant protests threatened boycott and terror, putting internal cohesion, national image and Olympic dream at stake. -

Bandurski (In Changing Media Changing China)

CHANGING MEDIA, CHANGING CHINA Edited by Susan L. Shirk OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 20II But the implications of these changes have also, like Lord Ye's dragon, caused alarm and consternation among leaders who strongly believe that controlling the public agenda is critical to maintaining social stability and the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP's) hold on power. While actively encouraging the media to operate on market principles instead of relying on government subsidies, the CCP resists a redefinition of the role of media, which it still regards first and foremost as promoters of the party's agenda. 2 Since the fllassacre of demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in 1989, "guid ance of public opinion," the most common euphemism for agenda control, has been the centerpiece of propaganda work! Nevertheless, media com China's Emerging Public Sphere: mercialization, developing norms of journalistic professionalism, and the growth of new media are combining to erode the CCP's monopoly over the The Impact of Media public agenda and to open a limited public sphere. The resulting tension between control and commercialization has Commercialization, altered the relationship between the CCP and the media, prompting the CCP to adopt new control tactics to uphold its influence on news and pro Professionalism, and the Internet paga nda. Despite the fact that the CCP continues to punish editors who step over the line and the media remain formally a part of the party-state in an Era of Transition apparatus, China's leaders are beginning to treat the media and Internet as Qian Gang and David Bandurski rhe voice of the public and to respond to it accordingly. -

The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations

The New Public Diplomacy Soft Power in International Relations Edited by Jan Melissen Studies in Diplomacy and International Relations General Editors: Donna Lee, Senior Lecturer in International Organisations and International Political Economy, University of Birmingham, UK and Paul Sharp, Professor of Political Science and Director of the Alworth Institute for International Studies at the University of Minnesota, Duluth, USA The series was launched as Studies in Diplomacy in 1994 under the general editorship of G. R. Berridge. Its purpose is to encourage original scholarship on all aspects of the theory and practice of diplomacy. The new editors assumed their duties in 2003 with a mandate to maintain this focus while also publishing research which demonstrates the importance of diplomacy to contemporary international relations more broadly conceived. Titles include: G. R. Berridge (editor) DIPLOMATIC CLASSICS Selected Texts from Commynes to Vattel G. R. Berridge, Maurice Keens-Soper and T. G. Otte DIPLOMATIC THEORY FROM MACHIAVELLI TO KISSINGER Herman J. Cohen INTERVENING IN AFRICA Superpower Peacemaking in a Troubled Continent Andrew F. Cooper (editor) NICHE DIPLOMACY Middle Powers after the Cold War David H. Dunn (editor) DIPLOMACY AT THE HIGHEST LEVEL The Evolution of International Summitry Brian Hocking (editor) FOREIGN MINISTRIES Change and Adaptation Brian Hocking and David Spence (editors) FOREIGN MINISTRIES IN THE EUROPEAN UNION Integrating Diplomats Michael Hughes DIPLOMACY BEFORE THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION Britain, Russia and the Old Diplomacy, 1894–1917 Gaynor Johnson THE BERLIN EMBASSY OF LORD D’ABERNON, 1920–1926 Christer Jönsson and Martin Hall ESSENCE OF DIPLOMACY Donna Lee MIDDLE POWERS AND COMMERCIAL DIPLOMACY British Influence at the Kennedy Trade Round Mario Liverani INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST, 1600–1100 BC Jan Melissen (editor) INNOVATION IN DIPLOMATIC PRACTICE THE NEW PUBLIC DIPLOMACY Soft Power in International Relations Peter Neville APPEASING HITLER The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson, 1937–39 M. -

How China, Turkey and Russia Influence the Media in Africa Dani Madrid- Morales

It is about their story How China, Turkey and Russia influence the media in Africa Dani Madrid- Morales Dani Madrid-Morales is an Assistant Professor of Journalism at the University of Houston, KAS Media where he teaches global communication. He has written Programme extensively on Africa-China media Sub-Sahara Africa relations. His work, based on extensive fieldwork in multiple The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung African countries, has appeared in (KAS) is an independent, leading academic journals. non-profit German political foundation that aims to strengthen democratic forces Deniz Börekci around the world. KAS runs Deniz Börekci is a researcher and media programmes in Africa, Asia translator based in Istanbul. She and South East Europe. focuses on Turkey’s domestic and international politics, and KAS Media Africa believes that sociology. a free and independent media is crucial for democracy. As such, it is committed to the Dieter Löffler development and maintenance of a diverse media landscape on Dieter Löffler is a political analyst, the continent, the monitoring role author and translator who lived in of journalism, as well as ethically Istanbul for many years. based political communication. Anna Birkevich Anna Birkevich is a Russian sociologist who lives in London. It is about their story How China, Turkey and Russia influence the media in Africa It is about their story How China, Turkey and Russia influence the media in Africa Published by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Regional Media Programme Sub-Sahara Africa 60 Hume Road PO Box 55012 Dunkeld 2196 Northlands Johannesburg 2116 Republic of South Africa Telephone: + 27 (0)11 214-2900 Telefax: +27 (0)11 214-2913/4 www.kas.de/mediaafrica Twitter: @KASMedia Facebook: @KASMediaAfrica ISBN: 978-0-620-91386 -7 (print) 978-0-620-91387- 4 (e-book) © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 2021 This publication is an open source publication. -

PEOPLE's REPUBLIC of CHINA: the HUMAN RIGHTS EXCEPTION ••' Roberta Cohen

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs • iN CoNTEMpORARY • AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 3 - 1988 (86) ., PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA: THE HUMAN RIGHTS EXCEPTION ••' Roberta Cohen ), Sckoolofl.Aw 1\ UNivERsiTy V of 0 •• MARylANd. c::; ' 0 Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Jaw-ling Joanne Chang Managing Editor: Chih-Yu Wu Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies Korea University, Republic of Korea All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $15.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $20.00 for overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS and sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu. Price for single copy of this issue: US $5.00 ISSN 0730-0107 ISBN 0-942182-89-8 PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA: THE HUMAN RIGHTS EXCEPTION Roberta Cohen TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ............................................. -

Overview of History, Origin and Development of the Mass Media in Northern Nigeria (1930-2014)

South East Asia Journal of Contemporary Business, Economics and Law, Vol. 8, Issue 3 (Dec.) 2015 ISSN 2289-1560 OVERVIEW OF HISTORY, ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE MASS MEDIA IN NORTHERN NIGERIA (1930-2014) Abdullahi Tafida Department of Economics, Faculty of Social and Management Sciences, Kaduna State University, P. M. B. 2339, Kaduna, Nigeria. Email: [email protected] , ABSTRACT This paper overviews the history, origin and development of mass media in Northern Nigeria from two angles, the print and the broadcast (the radio and television) media. The former print media) dates back to the 1920s, while the latter (broadcast media) dates back to the 1930s or thereabout. The objective of this paper is to critically examine the many sides of print and broadcast in the development of northern Nigeria with a view to identifying how far these media helped various governments in tackling their socioeconomic as well as political status of their citizens, where the data are collected from the secondary sources as the methodology. One of the major finding of this paper is that, both print and broadcast media have increased the literacy levels of the citizens of Northern Nigeria. Also this paper concludes and suggests that mass media helped various governments in forging the march needed unity and overall development of their environs. Key words: Radio, TV, Newspapers, Magazines, Cables. INTRODUCTION The mass media could be divided into two--print and broadcast (electronic). According to Okunna (1999), the electronic media of radio and television are distinct from other electronic media because they make use of transmission technology through which their signals are scattered far and wide.