Looking Behind the Scenes Project Management in the Motion Picture Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing

Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing Bethany Rooney and Mary Lou Belli AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK © 2011 Bethany Rooney and Mary Lou Belli. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. -

Bachelor's Degree in Filmmaking

BACHELOR’S DEGREE IN FILMMAKING THREE-YEAR ACCELERATED PROGRAM Each Bachelor of Fine Arts student writes, shoots, directs, and his Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree Program in Filmmaking employs a total immersion edits 12 films in the most intensive T approach to the subject where students hands-on program in the world develop a powerful arsenal of skills in directing, and works on the crew of at least screenwriting, cinematography, editing, and 30 additional films. producing. Students work in all formats from 16mm and HD to 35mm and RED Digital, as they write, direct, shoot, and edit their own films. A strong grounding in the liberal arts and sciences serves to inform students work and give them a well-rounded undergraduate education. The New York Film Academy’s Bachelor of Fine Arts in Filmmaking is unlike any other, it is an accelerated intensive degree program that can be completed in three years including summers. AVAILABLE IN One benefit of this is that students may begin internships or professional work a year earlier than they would in a standard bachelor’s program, and LOCATIONS of course save a year of tuition and expenses. UNIVERSAL STUDIOS, hollywood It requires a rigorous schedule whereby students are in class or production for eleven months of TUITION $30,000 PER YEAR** the year with a four week break between each **Additional Equipment Fee: $4,000 per year. Students will of the three years. Vacations are limited to two also incur additional expenses on their own productions. This varies depending on how much film they shoot and scale of weeks during the winter holidays and one week the projects. -

Script Breakdown

COMS 129 Fall 2008 PreProduction: Script Breakdown Script breakdown is the process of analyzing your script to determine all of the components out of which it is made. During script breakdown, you’ll systematically build lists of everything from characters, props and locations to special effects, and costumes. But script breakdown is much more than a simple inventory. The process of breaking down your script and the analysis and decisions you’ll make when doing your breakdown will generate the data that is required to prepare a budget and schedule your shoot. Breaking down a script is not just a suggestion, it is an essential step towards starting your production. During the script breakdown process you’re going to create a number of lists and schedules, but more importantly, you’re going to develop an understanding of your script that will be necessary for answering the thousands of questions that will come up during production. This familiarity with the script will allow to effectively deal with the changing conditions and concerns of a complex shoot. Depending on the length and nature of your script, you can use just about any method to break down your script. Obviously, there’s little to do if your script involves just one or two characters and is set on a single location. However, no matter how complicated your script, it’s important to perform a systematic, thorough breakdown. For simplicity, we’ve chosen to divide the realm of digital video production into two categories: A/V and Feature. A/V productions are the traditional industrial, corporate, multimedia or advertising productions that are usually small‐scale productions, frequently shot in a studio and rarely requiring more than a day or two of shooting. -

Edta Catalog

2019 CATALOG Honoring Theatre Students for 90 Years • THESPIAN APPAREL & SPIRIT • HONORS & TROPHIES • RESOURCES Check out these newly added items! THESPIAN SPIRIT 1 Apparel 1 Stickers & Magnets 4 Temporary Tattoos 5 Buttons 5 Games 5 Keyrings 6 pg. 3 Accessories 6 pg. 10 Gadgets 7 Pens & Paper 8 Decor 9 Bags 10 HONORS, AWARDS, TROPHIES, AND PLAQUES 11 For All Troupes 11 Thespian & Graduation Honors 11 Junior Thespian Honors 16 Banners 17 Awards 18 pg. 1 Trophies 19 Plaques 23 EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES 26 Classroom 26 Mime 32 Theatre Games & Improvisation 32 Acting & Directing 33 Vocal Technique & Singing 36 Film & Video 39 pg. 17 Multicultural 40 Middle School 41 Monologues 42 Technical Theatre 46 Careers 51 pg. 22 While They Last 52 No returns except damaged goods. No cash refunds. No returns after 30 days. Prices subject to change without notice. APPAREL APPAREL New ITS Limited Edition 90th anniversary apparel! ITS 90TH ANNIVERSARY CREWNECK SWEATSHIRT ITS 90TH ANNIVERSARY SHORT-SLEEVE T-SHIRT 100% cotton. Preshrunk. Sizes S - 2XL. White, ash, or 100% cotton. Preshrunk. Sizes S - 2XL. All apparel ships oxford. All apparel ships separately. RUSH service not separately. RUSH service not available. Allow 3 weeks for available. Allow 3 weeks for delivery. delivery. BASEBALL JERSEY - BLACK/GREY BASEBALL JERSEY - ROYAL BLUE/WHITE 425-PC78-9 MEMBER PRICE: $35.00 425-PC54-8 MEMBER PRICE: $25.00 100% cotton. ITS icon on the front. #ThespianNation 100% cotton. ITS icon on the front. #ThespianNation REGULAR PRICE: $40.00 REGULAR PRICE: $30.00 on the back. Aged look. Sizes S - 3XL. All apparel ships on the back. -

USC School of Cinema-Television

USC School of Cinema-Television he USC School of Cinema-Television offers undergraduate and graduate-level programs in production, critical studies, animation, writing for screen and television and producing. TThe school educates students in the aesthetic and technical values of the medium through course work, production activities and research. All members of the full-time cinema-television faculty have been or are working professionals in their respective fields; most have years of full-time professional experience. Each year a number of adjunct faculty from the Los Angeles film and television industries participate in all programs. Students at the USC School of Cinema-Television produce over 234 hours of motion pictures each year and complete approximately 100 full-length screenplays. USC films made by students receive 150 awards annually from festivals around the world. USC cinema-television alumni are among the most successful filmmakers and scholars working today. Since 1951, there have been only two years when no members of the Trojan Family were nominated for Academy Awards for their work USC’s School of Cinema-Television is number one according to the rankings published in America’s in documentary or fiction film. Best Graduate Schools issue of U.S. News and World Report (1998). The Cinema-Television Library offers a comprehensive collection of books in English and substantial holdings in other languages. The vast collection of journals, unpublished screenplays and manu- script materials includes personal papers of industry figures from the silent years to the present and studio records from Warner Bros., MGM, Universal and other producing companies. The study cen- ter also provides student access to the school’s large collection of film and television materials in all film and video formats as well as to several thousand recent screenplays. -

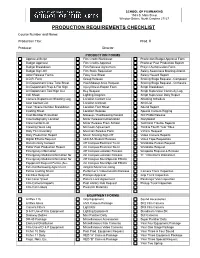

Production Requirements Checklist

SCHOOL OF FILMMAKING 1533 S. Main Street Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27127 PRODUCTION REQUIREMENTS CHECKLIST Course Number and Name: Production Title: Prod. # Producer: Director: PRODUCTION FORMS Approved Script Film Credit Worksheet Production Budget Approval Form Budget Approval Film Credits Approval Producer Post Production Report Budget Breakdown Film Release Agreement Project Authorization Form Budget Sign-Off Film Stock Requisition Safety Awareness Meeting Attend. Actor Release Forms Foley Cue Sheet Safety Hazard Report A.D.R. Form Group Release Scoring Stage Request - Composer Art Department Crew Time Sheet Hair/Makeup Artist Request Scoring Stage Request - Orchestra Art Department Prop & Flat Sign Injury/Illness Report Form Script Breakdown Art Department Tool Sign Out Key Request Script Supervisor Continuity Log Call Sheet Lighting Diagram Script Supervisor Daily Report Camera Department Shooting Log Location Contact List Shooting Schedule Cast Contact List Location Contract Shot List Cast / Scene Number Breakdown Location Fact Sheet Sound Report Casting Sheet Location Release Special Camera Rigging Cast Member Evaluation Makeup / Hairdressing Record Still Photo Release Cinematography Location Minor Release/Authorization Storyboard Crew Contact List Minor Release From School Technical Trouble Reports Crewing Hours Log Mix Lock Agreement Third & Fourth Year Titles Daily Film Inventory Musician Release Form Vehicle Request Daily Production Report Music Scoring Sign-Off Video Camera Reports Digital Effects Request UNCSA Student -

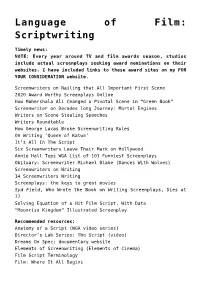

Language of Film: Scriptwriting

Language of Film: Scriptwriting Timely news: NOTE: Every year around TV and film awards season, studios include actual screenplays seeking award nominations on their websites. I have included links to these award sites on my FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION website. Screenwriters on Nailing that All Important First Scene 2020 Award Worthy Screenplays Online How Mahershala Ali Changed a Pivotal Scene in “Green Book” Screenwriter on Decades long Journey: Mortal Engines Writers on Scene Stealing Speeches Writers Roundtable How George Lucas Broke Screenwriting Rules On Writing ‘Queen of Katwe’ It’s All In The Script Six Screenwriters Leave Their Mark on Hollywood Annie Hall Tops WGA List of 101 Funniest Screenplays Obituary: Screenwriter Michael Blake (Dances With Wolves) Screenwriters on Writing 14 Screenwriters Writing Screenplays: the keys to great movies Syd Field, Who Wrote the Book on Writing Screenplays, Dies at 77 Solving Equation of a Hit Film Script, With Data “Moonrise Kingdom” Illustrated Screenplay Recommended resources: Anatomy of a Script (WGA video series) Director’s Lab Series: The Script (video) Dreams On Spec: documentary website Elements of Screenwriting (Elements of Cinema) Film Script Terminology Film: Where It All Begins Five Storytelling Tips to Make Your Online Videos More Effective How to analyze a screenplay How to: structure a film (video) Lesson Plans: Adapting A Scene for A Movie Script Formatting the Script Screenwriting: The Language of Film (from the AMPAS Teacher Guide Series) Scriptwriting (FiS) Scriptwriting 101 Writing -

The Director's Method in Contemporary Visual Effects Film

The Director’s Method in Contemporary Visual Effects Film: The Influence of Digital Effects on Film Directing Gianluca Balla PhD University of York Theatre, Film and Television September 2016 Abstract The director’ s method – meant as the organisation of the filmmaking process – is usually characterised by common procedures such as work on the script, shot design and the actors’ performance. For films involving a large-scale use of digital effects, directors consistently approach such procedures with a particular attitude dictated by the digital pipeline, the step-by- step technical procedure through which computer-generated images are created. In light of this, the use of digital effects might influence the director’s method. This thesis aims to define what is considered to be a consensual methodological approach to direct films with no or few digital effects and then compares this approach to when such effects are conspicuously involved. This analysis is conducted through interviews with working directors, visual effects companies and practitioners, and integrated with the current literature. The frame of the research is represented by a large spectrum of contemporary films produced in western countries and which involve digital effects at different scales and complexity but always in interaction with live-action. The research focuses on commercial films and excludes computer-animated and experimental films. The research is intended to address an area in production studies which is overlooked. In fact, although the existent literature examines both digital effects and film directing as distinct elements, there is to date no detailed analysis on the influence that the former has on the latter. -

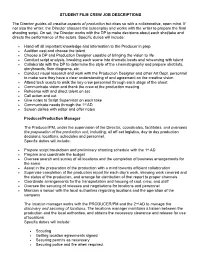

STUDENT FILM CREW JOB DESCRIPTIONS the Director Guides All Creative Aspects of Production but Does So with a Collaborative, Open

STUDENT FILM CREW JOB DESCRIPTIONS The Director guides all creative aspects of production but does so with a collaborative, open mind. If not also the writer, the Director chooses the screenplay and works with the writer to prepare the final shooting script. On set, the Director works with the DP to make decisions about each shot/take and directs the performance of the actors. Specific duties will include: • Hand-off all important knowledge and information to the Producer in prep • Audition cast and choose the talent • Choose a DP and Production Designer capable of bringing the vision to life • Conduct script analysis, breaking each scene into dramatic beats and rehearsing with talent • Collaborate with the DP to determine the style of the cinematography and prepare shot lists, storyboards, floor diagrams, etc. • Conduct visual research and work with the Production Designer and other Art Dept. personnel to make sure they have a clear understanding of and agreement on the creative vision • Attend tech scouts to walk the key crew personnel through each stage of the shoot • Communicate vision and thank the crew at the production meeting • Rehearse with and direct talent on set • Call action and cut • Give notes to Script Supervisor on each take • Communicate needs through the 1st AD • Screen dailies with editor and offer notes Producer/Production Manager The Producer/PM, under the supervision of the Director, coordinates, facilitates, and oversees the preparation of the production unit, including: all off-set logistics, day to day production -

Pre-Production Monday • Begin Script Breakdown. Producer/Dire

AVTF-II Filmmaking 2-Week Production Schedule and Rubric Week 1: Pre-Production Monday Begin script breakdown. Producer/Director assigns crew positions. Tuesday Continue script breakdown. Begin casting. Wednesday Secure location/talent releases. Complete script breakdown. Thursday Rehearse blocking and talent. Rehearse blocking and talent. All pre-production materials turned in. Friday (script breakdown, location releases, talent releases, cast and crew list) Week 2: Production/Post-Production Monday Location Shooting-Day 1 Tuesday Location shooting-Day 2 Wednesday Begin Rough Cut Thursday Rough Cut Complete Friday Final Cut Complete Individuals will rotate through each crew position every week. Responsibilities: Above the Line 1. Producer/Director: Oversee entire project. Assist Storyboard Artist. Work with Assistant Director on script breakdown. Work with DP to ensure all lighting and camera needs are met. Responsible for the set on shooting days. Work with Editor to complete and approve the final cut. 2. DP: Also called the Cinematographer. Responsible for lighting and camera set up. Works with director to assess needs. Will also serve as the camera operator on shooting days. 3. Editor: Responsible for editing the rough cut and final cut of the film. Will work as a P.A. on shooting days. 4. Talent: Cast members. Below the Line Assistant Director: Responsible for script breakdown. On shooting days will call out commands (except “Cut!”). Responsible for securing talent releases. Camera Assistant: Assists DP with camera and lighting set up. On shooting days will operate the slate (clapboard). Location Manager: Responsible for scouting locations and securing location releases Acts as a liaison between location officials and producer. -

A Gaffer's Perspective on Independent Filmmaking : Practices, Techniques, and Tricks of the Trade Revealed / Rick M

A Gaffer’s PERSPECTIVE on INDEPENDENT FILMMAKING A Gaff er’s PERSPECTIVE on INDEPENDENT FILMMAKING PRACTICES, TECHNIQUES and TRICKS of TRADE REVEALED RICK M. LORD Universal-Publishers Boca Raton A Gaffer’s Perspective on Independent Filmmaking: Practices, Techniques, and Tricks of the Trade Revealed Copyright © 2011 Rick M. Lord All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher Universal-Publishers Boca Raton, Florida • USA 2011 ISBN-10: 1-61233-059-2 ISBN-13: 978-1-61233-059-4 www.universal-publishers.com Cover photo © Kaarsten | Dreamstime.com Cover design by Shereen Siddiqui Layout by delaney-designs.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lord, Rick M., 1954- A gaffer's perspective on independent filmmaking : practices, techniques, and tricks of the trade revealed / Rick M. Lord. p. cm. ISBN-13: 978-1-61233-059-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-61233-059-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Independent films--Production and direction. 2. Cinematography. I. Title. PN1995.9.P7L67 2011 791.4302'32--dc23 2011035385 Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................9 PART ONE Chapter One REALITY CHECK .........................................................................................13 Big Budget versus No/Low Budget ........................................................14 -

Script Breakdown and Revision Procedures

PROCEDURES FOR SCRIPT BREAKDOWNS AND REVISIONS SCRIPT BREAKDOWN Lining and breaking down the script for production purposes is the first and one of the most important aspects of pre-production. Rendering the script into practical elements and breaking down scenes into isolated units allows the AD to prepare a detailed, easy-to- read shooting schedule and plan for the crew and cast and helps the producers and UPM to create a working budget. When preparing a locked script, each page and master scene must be numbered with whole, consecutive numbers. (May be done at time of “lock” by the writer, director or producer. If an AD or Script Supervisor receives a locked script with no scene numbers, each will assign scene numbers when they begin their separate breakdowns. Then, the AD, SS and Producer must confer to make sure their scene numberings are in agreement.) Do not assign prefixes or suffixes to scene numbers at this locked stage. POVs, flashbacks, and montages such as dream sequences should be assigned consecutive numbers where they fall in the script, just like other scenes. The shooting schedule is built from the locked script that has page and scene numbers on the right and left of the capitalized scene description. The scene numbers are the key to identifying all scenes from the start of pre-production to the end of post. The cast, production, crew, editorial and office staff will use the scene numbers to organize their work so these numbers must remain accurate and constant. Removal and re-numbering of scenes whether original, newly inserted, revised or omitted will cause major confusion.