Small Hydropower in Southern Africa – an Overview of Five Countries in the Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water for Food and Ecosystems in the Baviaanskloof Mega Reserve Land and Water Resources Assessment in the Baviaanskloof, Easter

Water for Food and Ecosystems in the Baviaanskloof Mega Reserve Land and water resources assessment in the Baviaanskloof, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa H.C. Jansen Alterra-report 1812 Alterra, Wageningen, 2008 ABSTRACT Jansen, H.C., 2008. Walerfor bood and hicosystems in the baviaanskloofMega Reserve. IMnd and water resources assessment in the Baviaanskloof,Hastern Cape Province, South Africa. Wageningen, Alterra, Alterra-report 1812. 80 pages; 21 figs.; 6 tables.; 18 refs. This report describes the results of the land and water assessment for the project 'Water for Food and Ecosystems in the Baviaanskloof Mega Reserve'. Aim of the project is to conserve the biodiversity in a more sustainable way, by optimizing water for ecosystems, agricultural and domestic use, in a sense that its also improving rural livelihoods in the Baviaanskloof. In this report an assessment of the land and water system is presented, which forms a basis for the development and implementation of land and water policies and measures. Keywords: competing claims, IWRM, land management, nature conservation, policy support, water management, water retention ISSN 1566-7197 The pdf file is tree of charge and can he downloaded vi«i the website www.ahctra.wur.nl (go lo Alterra reports). Alterra docs not deliver printed versions ol the Altena reports. Punted versions can be ordered via the external distributor. I-or oidcrmg have a look at www.li tx> ni l) ljtl.nl/mppcirtc ilser vice . © 2008 Alterra P.O. Box 47; 6700 AA Wageningen; The Netherlands Phone: + 31 317 484700; fax: +31 317 419000; e-mail: info.alterra@,wur.nl No part of this publication may be reproduced or published in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system without the written permission of Alterra. -

Overview of the South African Coal Value Chain

SOUTH AFRICAN COAL ROADMAP OVERVIEW OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN COAL VALUE CHAIN PREPARED AS A BASIS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN COAL ROADMAP OCTOBER 2011 Overview of the South African Coal Value Chain | I Disclaimer: The statements and views of the South African Coal Roadmap are a consensus view of the participants in the development of the roadmap and do not necessarily represent the views of the participating members in their individual capacity. An extensive as reasonably possible range of information was used in compiling the roadmap; all judgments and views expressed in the roadmap are based upon the information available at the time and remain subject to further review. The South African Coal Roadmap does not guarantee the correctness, reliability or completeness of any information, judgments or views included in the roadmap. All forecasts made in this document have been referenced where possible and the use and interpretation of these forecasts and any information, judgments or views contained in the roadmap is entirely the risk of the user. The participants in the compiling of this roadmap will not accept any liability whatsoever in respect of any information contained in the roadmap or any statements, judgments or views expressed as part of the South African Coal Roadmap. SYNTHESIS enables a wide range of stakeholders to discuss the future of the industry. The fact that at this stage in the process Phase The South African Coal Roadmap (SACRM) process I does not provide any clarity on the outlook for the South African coal industry is o"set by the constructive process The need for a Coal Roadmap for South Africa was identi!ed which has been initiated, which augurs well for the successful in 2007 by key role players in the industry, under the auspices development of a South African Coal Roadmap in Phase II. -

Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas of South Africa

IMPORTANT BIRD AND BIODIVERSITY AREAS of South Africa INTRODUCTION 101 Recommended citation: Marnewick MD, Retief EF, Theron NT, Wright DR, Anderson TA. 2015. Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas of South Africa. Johannesburg: BirdLife South Africa. First published 1998 Second edition 2015 BirdLife South Africa’s Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas Programme acknowledges the huge contribution that the first IBA directory (1998) made to this revision of the South African IBA network. The editor and co-author Keith Barnes and the co-authors of the various chapters – David Johnson, Rick Nuttall, Warwick Tarboton, Barry Taylor, Brian Colahan and Mark Anderson – are acknowledged for their work in laying the foundation for this revision. The Animal Demography Unit is also acknowledged for championing the publication of the monumental first edition. Copyright: © 2015 BirdLife South Africa The intellectual property rights of this publication belong to BirdLife South Africa. All rights reserved. BirdLife South Africa is a registered non-profit, non-governmental organisation (NGO) that works to conserve wild birds, their habitats and wider biodiversity in South Africa, through research, monitoring, lobbying, conservation and awareness-raising actions. It was formed in 1996 when the IMPORTANT South African Ornithological Society became a country partner of BirdLife International. BirdLife South Africa is the national Partner of BirdLife BIRD AND International, a global Partnership of nature conservation organisations working in more than 100 countries worldwide. BirdLife South Africa, Private Bag X5000, Parklands, 2121, South Africa BIODIVERSITY Website: www.birdlife.org.za • E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: +27 11 789 1122 • Fax: +27 11 789 5188 AREAS Publisher: BirdLife South Africa Texts: Daniel Marnewick, Ernst Retief, Nicholas Theron, Dale Wright and Tania Anderson of South Africa Mapping: Ernst Retief and Bryony van Wyk Copy editing: Leni Martin Design: Bryony van Wyk Print management: Loveprint (Pty) Ltd Mitsui & Co. -

Dr. Mathys Vosloo

Dr. Mathys Vosloo KEY EXPERIENCE Professional Registrations: Dr. Mathys Vosloo is a well-qualified and technically proficient environmental • (SACNASP) South African and natural scientist with more than 12 years environmental management Council for Natural Scientific experience. His experience include Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) Professions and the development of Environmental Management Programmes during • (IAIAsa) International environmental assessments of construction projects, environmental Association for Impact Assessment – South Africa compliance monitoring and reporting, and Environmental Control Officer (ECO) services for construction projects. Recent experience includes project management and execution of large waste related projects, such as the application for development of Ash Disposal Facilities, and large linear projects such as the management EIA process for the implementation of extensive power lines for renewable projects. Mathys also has substantial experience in Occupation: Geographical Information Systems (GIS), creating and analysing digital terrain models, runoff and stream flow analysis, stormwater design and map-making • Senior Environmental for projects in Africa. Further experience include the development and Scientist completion of State Of the Environment Reporting (SOER), Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEA) and feasibility studies. Mathys’ experience in natural science include aquatic ecological assessments, project management and sample collection in several west, south and east coast -

University of Cape Town

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University University of Cape Town Economics Department Water Supply in the Eastern Cape An economic case study of land rehabilitation in the Kromme River Catchment Masters of Commerce in Economics by dissertation only Katie Gull GLLKAT005 Town Supervisor: Prof. Anthony Leiman Cape of University 1 Declaration I, Katie Gull, hereby declare that the work on which the thesis is based is my original work (except where acknowledgements indicate otherwise) and that neither the whole work or any part of it has been, is being, or is to be submitted for another degree in this or any university. I authorise the University to reproduce for the purpose of research either the whole or any portion of the contents in any matter whatsoever. Signature: Date: Town Cape of University 2 Executive Summary South Africa is a water scarce country; with a mean annual precipitation of only 600 mm in 70% of the country and one of the lowest rain-runoff conversions in the world. South Africa consumes 31% of the available water resources, a high percentage by world’s standards (National Planning Commission, 2011). Analysts predict that as South Africa approaches 40% consumption, South Africa will face a binding water constraint. -

Investigating the Operational Behaviour of a Double Curvature Arch Dam

FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL ENGINEERING INVESTIGATING THE OPERATIONAL BEHAVIOUR OF A DOUBLE CURVATURE ARCH DAM By Zac James Prins Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree University of Cape Town M.Eng. Civil Infrastructure Management and Maintenance Supervisor: Professor Pilate Moyo The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town PLAGIARISM DECLARATION I know the meaning of plagiarism and declare that all the work in the document, save for that which is properly acknowledged, is my own. This thesis/dissertation has been submitted to the Turnitin module (or equivalent similarity and originality checking software) and I confirm that my supervisor has seen my report and any concerns revealed by such have been resolved with my supervisor. Signature Removed Signature: ______________________ Date: 12 May 2017 i DEDICATION To my loving family for their unwavering support. ii ABSTRACT The safety of dams is crucial in ensuring the continual availability of water, safety of the surrounding communities and infrastructure. Surveillance systems are implemented to monitor the structural integrity of certain dams which have a safety risk. The components and extent of the surveillance systems adopted depends on many factors, which include the type of dam wall structure used to impound the reservoir, geotechnical and environmental conditions. -

Tender Bulletin: 5 April 2013

, 4 Government Tender Bulletin REPUBLICREPUBLIC OF OF SOUTH SOUTH AFRICAAFRICA Vol. 574 Pretoria, 5 April 2013 No. 2768 This document is also available on the Internet on the following web sites: 1. http://www.treasury.gov.za 2. http://www.info.gov.za/documents/tenders/index.htm N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINEHELPLINE: 08000800-123-22 123 22 PreventionPrevention is is the the cure cure 301348—A 2768—1 2 GOVERNMENT TENDER BULLETIN, 5 APRIL 2013 INDEX Page No. Instructions.................................................................................................................................. 8 A. BID INVITED FOR SUPPLIES, SERVICES AND DISPOSALS SUPPLIES: CLOTHING/TEXTILES .................................................................................. 10 ١ SUPPLIES: GENERAL...................................................................................................... 11 ١ SUPPLIES: MEDICAL ....................................................................................................... 11 ١ SERVICES: BUILDING ..................................................................................................... 12 ١ SERVICES: CIVIL ............................................................................................................. 12 ١ SERVICES: FUNCTIONAL (INCLUDING CLEANING AND SECURITY SERVICES)...... 12 ١ SERVICES: GENERAL .................................................................................................... -

Lennart Van Der Burg 2008 Benefits Restoring Water Regulation Gamtoos.Pdf

This file has been cleaned of potential threats. If you confirm that the file is coming from a trusted source, you can send the following SHA-256 hash value to your admin for the original file. 9acd8e58dac86ab333098d0889ad4834f68769800cbc7fe022c978ea5c39af14 To view the reconstructed contents, please SCROLL DOWN to next page. Valuing the benefits of restoring the water regulation services, in the subtropical thicket biome: a case study in the ‘Baviaanskloof-Gamtoos watershed’, South-Africa Lennart van der Burg October 2008 i Valuing the benefits of restoring the water regulation services, in the subtropical thicket biome: a case study in the ‘Baviaanskloof-Gamtoos watershed’, South-Africa Lennart van der Burg Supervisors: Dr.Rolf Groeneveld Environmental Economics and Matthew Zylstra, Natural Resources Group Dieter van den Broeck, [email protected] EarthCollective Dr Dolf de Groot, Email: [email protected] Environmental Systems Analysis group, [email protected] Wageningen UR PO Box 47, 6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands Email: [email protected] A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Science at Wageningen University, the Netherlands. Master thesis project assigned by the Subtropical Thicket Restoration Programme - STRP, South Africa. Co-funded and supported by the Speerpunt Ecosysteem- en Landschap Services (SELS)- WUR, Department of Water Affairs and Forestry – DWAF/Working for Water and Gamtoos Irrigation Board - GIB, South Africa. In collaboration with Rhodes Restoration Research Group - R3G, South Africa. Facilitated by PRESENCE learning network and EarthCollective. Front page Pictures: Kouga Dam reservoir (l) and an aerial photo of the start of the Gamtoos valley wit h the Baviaanskloof watershed in the background (r). -

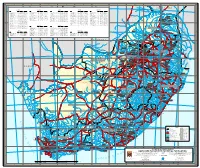

I Ndian Ocean a T L a N T Ic O C E

A B C D E F G H J K L 16°E 18°E 20°E 22°E 24°E 26°E 28°E 30°E 32°E S h a s h e M otloutse Tuli Z I M B A B W E Th EASTERN CAPE FREE STATE LIMPOPO NORTH WEST WESTERN CAPE u ne Dam Index Latitude Longitude Dam Index Latitude Longitude Dam Index Latitude Longitude Dam Index Latitude Longitude Dam Index Latitude Longitude 22°S Limpopo Binfield Park Dam.........G8 S32°41'56.8" E26°54'46.6" Allemanskraal Dam.........H5 S28°17'15.9" E27°08'49.4" Albasini Dam..............K2 S23°06'26.0" E30°07'29.0" Bloemhof Dam..............G4 S27°39'52.1" E25°37'11.7" Beaufort West Dam.........E8 S32°20'39.5" E22°35'07.7" Beitbridge 22°S Bushmans Krantz Dam.......G8 S32°21'26.3" E26°40'38.4" Armenia Dam...............H6 S29°21'52.3" E27°07'40.9" Damani Groot Dam..........K1 S22°51'05.2" E30°30'55.9" Boskop Dam................H4 S26°33'41.0" E27°06'41.6" Berg River Dam............C9 S33°54'21.1" E19°03'19.0" Cata Dam..................H8 S32°37'52.9" E27°07'02.8" Erfenis Dam...............G5 S28°30'35.7" E26°46'40.9" Doorndraai Dam............J2 S24°16'48.6" E28°46'37.1" Bospoort Dam..............H3 S25°33'45.4" E27°19'35.5" Buffeljags Dam............D9 S34°01'07.2" E20°32'03.0" 1 Darlington Dam............F8 S33°12'20.3" E25°08'54.4" Fika Patsu Dam............J5 S28°40'21.1" E28°51'24.1" Ebenezer Dam..............J2 S23°56'27.3" E29°59'05.9" Buffelspoort Dam..........H3 S25°46'49.3" E27°29'12.9" Bulshoek Dam..............C7 S31°59'45.8" E18°47'13.7" Musina 1 d De Mistkraal Weir.........G8 S32°57'28.9" E25°40'27.8" Gariep Dam................G6 S30°37'22.1" E25°30'23.7" -

Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality State of the Environment Report

NELSON MANDELA BAY MUNICIPALITY STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT REPORT J29079 February 2011 NELSON MANDELA BAY MUNICIPALITY STATE OF ENVIRONMENT REPORT We are only as healthy as the world we live in Prepared by Dr N. Klages, assisted by J. Jegels, I. Schovell and M. Vosloo, of Arcus GIBB (Pty) Ltd for Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality. NMBM SOER 1 NELSON MANDELA BAY MUNICIPALITY STATE OF ENVIRONMENT REPORT STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT REPORT CONTENTS Chapter Description Page 1 SUMMARY EVALUATION 11 2 INTRODUCTION 20 2.1 What is a State of the Environment Report? 20 2.2 Background to State of the Environment Reports 20 3 LEGAL FRAMEWORK 21 3.1 Constitution of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996) 21 3.2 National Environmental Management Act (Act 107 of 1998) 21 3.3 National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (Act 10 of 2004) 22 3.4 Municipal Systems Act (Act 32 of 2000) 22 3.5 Promotion of Access to Information Act (Act No. 2 of 2000) 22 3.6 Local Agenda 21 23 4 BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT 24 4.1 Topography 24 4.2 Geology and soils 26 4.3 Weather and climate 27 4.4 Flora and fauna 28 4.5 Demographics 30 4.6 History 32 4.7 Political administration 33 4.8 Economy 35 NMBM SOER 2 NELSON MANDELA BAY MUNICIPALITY STATE OF ENVIRONMENT REPORT 5 THEME: LAND 37 5.1 Introduction 37 5.2 Drivers and pressure s 37 5.3 State 38 5.4 Indicators 45 5.5 Impacts 45 5.6 Responses 45 5.7 Linkages and inter-dependencies 48 6 THEME: CLIMATE CHANGE AND AIR QUALITY 49 6.1 Introduction 49 6.2 Drivers and pressure s 51 6.3 State 52 6.4 Indicators 58 6.5 -

Kouga Dam Desktop Hydrological Study Report

KOUGA DAM REHABILITATION PROJECT DESKTOP HYDROLOGY ASSESSMENT REPORT Kouga Dam Rehabilitation Project Desktop Hydrology Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 2 2 SITE DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................................... 3 3 HYDROLOGY ................................................................................................................ 6 3.1 Potential Alluvial Mining Impacts – Scour ................................................................ 6 3.2 Potential Alluvial Mining Impacts – Sediment Transport .......................................... 8 4 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................. 10 5 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................ 12 T:\ACTIVE PROJECTS\41232 – Kouga Dam Study (PH)\04 Documents and Reports\J&G Reports Page i of i Kouga Dam Rehabilitation Project Desktop Hydrology Assessment 1 INTRODUCTION Jeffares & Green (Pty) Ltd have been appointed by GIBB (Pty) Ltd to undertake a hydrological desktop assessment of the potential impacts of the planned alluvial mining activity downstream of the Kouga Dam wall, located approximately 36 km east of Humansdorp in the Eastern Cape. It is planned that the mining activity will provide fill and road construction material for the rehabilitation of the Kouga Dam wall and upgrade -

EC108 Kouga Annual Report 2005-06

1 ANNUAL REPORT 2005/2006 Kouga Municipality: Tel: 042 293 1111 The Municipal Manager Fax: 042 293 1114 P.O. Box 21 Email: [email protected] KOUGA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY’S ANNUAL REPORT 2005/06 2 Jeffreys Bay, 6330 [email protected] W A R D C O U N C I L L O R S WARD NAME ADDRESS TEL.NO. CELL. NO. Ward 1 B Rheeder P O Box 228 042-2980269 St Francis Bay 6312 Ward 2 R Dennis 15 Rob Street 042-2932651 083 687 7757 Jeffreys Bay 6330 Ward 3 F Cloete P O Box 59 042-2961234 082 651 2623 Jeffreys Bay 6330 Ward 4 V Stuurman P O Box 625 083 350 6022 Humansdorp 6300 Ward 5 H Coenraad 26 Hobson Street 042-2911478 083 670 7738 Humansdorp 6300 Ward 6 N Majola P O Box 1035 042-2952302 072 427 3393 Humansdorp 6300 Ward 7 E Ungerer P O Box 3 042-2931056 082 442 8710 Jeffreys Bay 6330 Ward 8 A Mabukane 33 Prina Street 042-2830563 083 6555 173 Patensie 042-2830623 6335 Ward 9 M Tshume P O Box 3 082 724 0544 Hankey 6350 Ward 10 F Lloyd P O Box 1540 084 514 3782 Thornhill 6375 KOUGA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY’S ANNUAL REPORT 2005/06 3 PR COUNCILLORS NAME ADDRESS TEL. NO. CELL. NO. J Cawood P O Box 241 042-2940025 083 516 9560 St Francis Bay 6312 H Plaatjies P O Box 448 042-2840122 072 480 8281 Hankey 6350 NAME ADDRESS TEL. NO. CELL. NO.