ON OCTOBER 13, 2011 I. Introduction Chairman Akaka, Vice-Chairman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Komure Elementary School High Schooler Emily Isakari Headed Back to Her Booth at the School’S Festival

PAGE 4 Animeʼs uber populatiy. PAGE 9 Erika Fong the WHATʼS Pink Power Ranger IN A NAME? Emily Isakari wants the world to know about George Komure. PAGE 10 JACL youth in action PAGE 3 at youth summit. # 3169 VOL. 152, NO. 11 ISSN: 0030-8579 WWW.PACIFICCITIZEN.ORG June 17-30, 2011 2 june 17-30, 2011 LETTERS/COMMENTARY PACIFIC CITIZEN HOW TO REACH US E-mail: [email protected] LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Online: www.pacificcitizen.org Tel: (213) 620-1767 Food Issue: Yummy Fax: (213) 620-1768 Power of Words Resolution Connecting JACLers Mail: 250 E. First Street, Suite 301 The “Power of Words” handbook, which is being developed to Across the Country Great issue! Made me hungry Los Angeles, CA 90012 implement the Power of Words resolution passed at the 2010 Chicago just reading about the passion and StaFF JACL convention, was sent electronically to all JACL chapter Since the days when reverence these cooks have for Executive Editor Caroline Y. Aoyagi-Stom presidents recently. I would like all JACL members to take a close headquarters was in Utah and all food. How about another special look at this handbook, especially the section titled: “Which Words Are the folks involved in suffering issue (or column) featuring Assistant Editor Lynda Lin Problematic? … And Which Words Should We Promote?” during World War II, many of some of our members and their Who labeled these words as “problematic?” The words are them our personal friends, my interesting hobbies? Reporter euphemisms and we should not use them. There are words that can be wife Nellie and I have enjoyed and Keep up the wonderful work; I Nalea J. -

PPM138 Women in Senate Glossy

WOMEN IN THE SENATE CO LITI O hinkle — p S HN O Y J B From left: Sens. OS Barbara Mikul- T O ski of Mary- PH land, Dianne Feinstein of California, and Olympia Snowe and Susan Col- lins of Maine is that she’s been on all the major committees is the only senator to chair two — Ethics and and deeply engaged in every moving issue of our Environment and Public Works. time.” The women owe some of their success to They may not always get the respect, but Mikulski. As the unofficial “dean” of the women’s EYE-OPENER behind the scenes, female senators more caucus, the Maryland Democrat has acted as a den The Magnificent Seven frequently are getting what they want. Schroeder mother to 11 classes of new female senators. HOLIDAY WEEKEND BRUNCH u u u remembers having to plead with powerful When Mikulski first came into the Senate, committee chairmen to get the funding requests she sought out mentors to help her navigate its SUN. & MON., OCT. 11 & 12 • 11AM–3PM of congresswomen heard. complicated and often arcane rules. She turned “They would say, ‘Now, what can I pass for to Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts and Paul NEW ORLEANS PIANO • HURRICANE HOWIE From what was a record high of seven female senators elected in 1992, you girls that won’t cost us any money and will Sarbanes, her Senate colleague from Maryland, BREAKFAST CAFE • BAR make all the women love us?’” she says. calling the two Democrats her “Sir Galahads.” women have gained in numbers – and seniority No one asks those kinds of questions when They helped her land a seat on the powerful LUNCH • DINNER BOOKSTORE women hold the gavel. -

THE AMERICAN POWER All- Stars

THE AMERICAN POWER All- Stars Scorecard & Voting Guide History About every two years, when Congress takes up an energy bill, the Big Oil Team and the Clean Energy Team go head to head on the floor of the U.S. Senate -- who will prevail and shape our nation’s energy policy? The final rosters for the two teams are now coming together, re- flecting Senators’ votes on energy and climate legislation. Senators earn their spot on the Big Oil Team by voting to maintain America’s ailing energy policy with its en- trenched big government subsidies for oil companies, lax oversight on safety and the environment for oil drilling, leases and permits for risky sources of oil, and appointments of regulators who have cozy relationships with the industry. Senators get onto the Clean Energy Team by voting for a new energy policy that will move Amer- ica away from our dangerous dependence on oil and other fossil fuels, and toward cleaner, safer sources of energy like wind, solar, geothermal, and sustainable biomass. This new direction holds the opportunity to make American power the energy technology of the future while creating jobs, strengthening our national security, and improving our environment. Introduction Lobbyists representing the two teams’ sponsors storm the halls of the Congress for months ahead of the votes to sway key players to vote for their side. The Big Oil Team’s sponsors, which include BP and the American Petroleum Institute (API), use their colossal spending power to hire sly K-Street lobbyists who make closed-door deals with lawmakers, sweetened with sizable campaign contribu- tions. -

Miscellaneous National Parks Legislation Hearing

S. HRG. 110–266 MISCELLANEOUS NATIONAL PARKS LEGISLATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON S. 128 S. 1476 S. 148 S. 1709 S. 189 S. 1808 S. 697 S. 1969 S. 867 H.R. 299 S. 1039 H.R. 1239 S. 1341 SEPTEMBER 27, 2007 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 40–443 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico, Chairman DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho RON WYDEN, Oregon LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD BURR, North Carolina MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JIM DEMINT, South Carolina MARIA CANTWELL, Washington BOB CORKER, Tennessee KEN SALAZAR, Colorado JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama BLANCHE L. LINCOLN, Arkansas GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon BERNARD SANDERS, Vermont JIM BUNNING, Kentucky JON TESTER, Montana MEL MARTINEZ, Florida ROBERT M. SIMON, Staff Director SAM E. FOWLER, Chief Counsel FRANK MACCHIAROLA, Republican Staff Director JUDITH K. PENSABENE, Republican Chief Counsel SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii, Chairman BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota RICHARD BURR, North Carolina MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska KEN SALAZAR, Colorado BOB CORKER, Tennessee ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming BLANCHE L. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Congressional Record—Senate S6769

December 7, 2016 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S6769 don’t ask, don’t tell. He signed Execu- streak of private sector job growth from the House came over in the midst tive orders protecting LGBT workers. ever. We have the lowest unemploy- of all their work. I love them. I have Americans are now free to marry the ment rate in nearly a decade. enjoyed working with them. person they love, regardless of their After 8 years of President Obama, we I look around this Chamber, and I re- gender. are now as a country on a sustainable alize the reason I am able to actually As Commander in Chief, President path to fight climate change and grow leave is because I know each of you and Obama brought bin Laden to justice. renewable energy sources. We are more your passion to make life better for These are just a few aspects of Presi- respected around the world. We reached people, and that is what it is all about. dent Obama’s storied legacy, and it is international agreements to curb cli- When I decided not to run for reelec- still growing—what a record. It is a mate change, stop Iran from obtaining tion, you know how the press always legacy of which he should be satisfied. a nuclear weapon, and we are on the follows you around. They said: ‘‘Is this America is better because of this good path to normalizing relations with our bittersweet for you?’’ man being 8 years in the White House. neighbor Cuba. My answer was forthcoming: ‘‘No I am even more impressed by who he Our country has made significant way is it bitter. -

Oversight Hearing Committee on Natural Resources

COMPARING 21ST CENTURY TRUST LAND ACQUISITION WITH THE INTENT OF THE 73RD CONGRESS IN SECTION 5 OF THE INDIAN RE- ORGANIZATION ACT OVERSIGHT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INDIAN, INSULAR AND ALASKA NATIVE AFFAIRS OF THE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Thursday, July 13, 2017 Serial No. 115–15 Printed for the use of the Committee on Natural Resources ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov or Committee address: http://naturalresources.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 26–253 PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 10:44 Sep 18, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 J:\115TH CONGRESS\INDIAN, INSULAR & ALASKA NATIVE AFFAIRS\07-13-17\26253.TXT COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES ROB BISHOP, UT, Chairman RAU´ L M. GRIJALVA, AZ, Ranking Democratic Member Don Young, AK Grace F. Napolitano, CA Chairman Emeritus Madeleine Z. Bordallo, GU Louie Gohmert, TX Jim Costa, CA Vice Chairman Gregorio Kilili Camacho Sablan, CNMI Doug Lamborn, CO Niki Tsongas, MA Robert J. Wittman, VA Jared Huffman, CA Tom McClintock, CA Vice Ranking Member Stevan Pearce, NM Alan S. Lowenthal, CA Glenn Thompson, PA Donald S. Beyer, Jr., VA Paul A. Gosar, AZ Norma J. Torres, CA Rau´ l R. Labrador, ID Ruben Gallego, AZ Scott R. -

To Senator Daniel Akaka and the United States Committee on Indian Affairs

To Senator Daniel Akaka and the United States Committee on Indian Affairs, Please find below the written testimony of Alvin N. Parker, Principal of Ka Waihona o ka Naauao Public Charter School, for the oversight hearing on “In Our Way: Expanding the Success of Native Language & Culture-Based Education” on Thursday, May 26, 2011, beginning at 2:15 p.m. in room 628 of the Dirksen Senate Office Building. Mahalo, Alvin N. Parker Principal Ka Waihona o ka Naauao Public Charter School 89-195 Farrington Highway Waianae, Hawaii 96792 (808)620-9030 www.kawaihonapcs.org Ka Waihona o ka Naauao (KWON) is located on the Wai`anae Coast, the western side of the island of O`ahu. The Wai‟anae community, as many Native American communities, has experienced rampant alcohol, sexual and substance abuse, early teen pregnancy, a large percentage of Native Hawaiians incarcerated, and the disintegration of family and Native Hawaiian values due to the above listed social maladies. The mission of Ka Waihona o ka Na`auao is to create socially responsible, resilient and resourceful young men and women by providing an environment of academic excellence, social confidence and cultural awareness. Because of this, KWON embraces a curriculum that is both academically rigorous and culturally sensitive. KWON houses opened ten years ago in an educationally altered chicken coop with 60 students in grades kindergarten through three. Currently, there are 572 students in 24 classrooms in grades kindergarten through eight on a traditional school campus. Of our students, 93% are Native Hawaiian and 62% are economically disadvantaged. Each class has an educational assistant in addition to a classroom teacher which allows for a lower student-teacher ratio and more effective classroom management. -

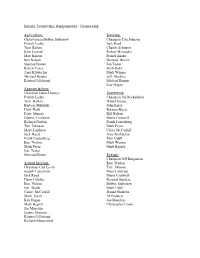

Senate Committee Assignments - Democrats

Senate Committee Assignments - Democrats: Agriculture: Banking: Chairwoman Debbie Stabenow Chairman Tim Johnson Patrick Leahy Jack Reed Tom Harkin Charles Schumer Kent Conrad Robert Menendez Max Baucus Daniel Akaka Ben Nelson Sherrod Brown Sherrod Brown Jon Tester Robert Casey Herb Kohl Amy Klobuchar Mark Warner Michael Bennet Jeff Merkley Kirsten Gillibrand Michael Bennet Kay Hagan Appropriations: Chairman Daniel Inouye Commerce: Patrick Leahy Chairman Jay Rockefeller Tom Harkin Daniel Inouye Barbara Mikulski John Kerry Herb Kohl Barbara Boxer Patty Murray Bill Nelson Dianne Feinstein Maria Cantwell Richard Durbin Frank Lautenberg Tim Johnson Mark Pryor Mary Landrieu Claire McCaskill Jack Reed Amy Klobuchar Frank Lautenberg Tom Udall Ben Nelson Mark Warner Mark Pryor Mark Begich Jon Tester Sherrod Brown Energy: Chairman Jeff Bingaman A rmed Services: Ron Wyden Chairman Carl Levin Tim Johnson Joseph Lieberman Mary Landrieu Jack Reed Maria Cantwell Daniel Akaka Bernard Sanders Ben Nelson Debbie Stabenow Jim Webb Mark Udall Claire McCaskill Jeanne Shaheen Mark Udall Al Franken Kay Hagan Joe Manchin Mark Begich Christopher Coons Joe Manchin Jeanne Shaheen Kirsten Gillibrand Richard Blumenthal Environment and Public Works: Health, Education, Labor and Pension: Chairwoman Barbara Boxer Chairman Tom Harkin Max Baucus Barbara Mikulski Thomas Carper Jeff Bingaman Frank Lautenberg Patty Murray Benjamin Cardin Bernard Sanders Bernard Sanders Robert Casey Sheldon Whitehouse Kay Hagan Tom Udall Jeff Merkley Jeff Merkley Al Franken Kirsten Gillibrand -

Daniel K. Akaka

Daniel K. Akaka U.S. SENATOR FROM HAWAII TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES E PL UR UM IB N U U S VerDate Aug 31 2005 16:21 Apr 17, 2014 Jkt 081101 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE12\81101.TXT KAYNE congress.#15 Courtesy U.S. Senate Historical Office Daniel K. Akaka VerDate Aug 31 2005 16:21 Apr 17, 2014 Jkt 081101 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6688 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE12\81101.TXT KAYNE 81101.eps S. DOC. 113–3 Tributes Delivered in Congress Daniel K. Akaka United States Congressman 1977–1990 United States Senator 1990–2013 ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2014 VerDate Aug 31 2005 16:21 Apr 17, 2014 Jkt 081101 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE12\81101.TXT KAYNE Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing VerDate Aug 31 2005 16:21 Apr 17, 2014 Jkt 081101 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE12\81101.TXT KAYNE CONTENTS Page Biography .................................................................................................. v Farewell Address ...................................................................................... xi Proceedings in the Senate: Tributes by Senators: Blunt, Roy, of Missouri .............................................................. 17 Cardin, Benjamin L., of Maryland ............................................ 18 Collins, Susan M., of Maine ...................................................... 11 Conrad, Kent, of North Dakota ................................................ -

Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2009 Reapportionment Following the 1960 Cen- Percent Casting Votes in Each State for Sus

Section 7 Elections This section relates primarily to presiden- 1964. In 1971, as a result of the 26th tial, congressional, and gubernatorial Amendment, eligibility to vote in national elections. Also presented are summary elections was extended to all citizens, tables on congressional legislation; state 18 years old and over. legislatures; Black, Hispanic, and female officeholders; population of voting age; Presidential election—The Constitution voter participation; and campaign specifies how the president and vice finances. president are selected. Each state elects, by popular vote, a group of electors equal Official statistics on federal elections, col- in number to its total of members of Con- lected by the Clerk of the House, are pub- gress. The 23d Amendment, adopted in lished biennially in Statistics of the Presi- 1961, grants the District of Columbia dential and Congressional Election and three presidential electors, a number Statistics of the Congressional Election. equal to that of the least populous state. Federal and state elections data appear also in America Votes, a biennial volume Subsequent to the election, the electors published by CQ Press (a division of Con- meet in their respective states to vote for gressional Quarterly, Inc.), Washington, president and vice president. Usually, DC. Federal elections data also appear in each elector votes for the candidate the U.S. Congress, Congressional Direc- receiving the most popular votes in his or tory, and in official state documents. Data her state. A majority vote of all electors is on reported registration and voting for necessary to elect the president and vice social and economic groups are obtained president. -

HILL UPDATES Ranking Member: Rep

ISSUE 11 - 1 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2011 House Committee on Natural Resources I NSIDE T HIS I SSUE Chairman: Rep. Doc Hastings (R-WA) Ranking Member: Rep. Ed Markey (D-MA) - New Congressional Committee Chairs Subcommittee on Indian and Alaska Native Affairs - Update on Appropriations Chairman: Rep. Don Young (R-AK) - Tribal Consultation Ranking Member: Rep. Dan Boren (D-OK) House Committee on Ways and Means Chairman: Rep. Dave Camp (R-MI) HILL UPDATES Ranking Member: Rep. Sander Levin (D-MI) New Leadership in the 112th Congress Subcommittee on Health Chairman: Rep. Wally Herger (R-CA) With a change in majority for the House and a Ranking Member: Rep. Fortney Pete Stark retirement in the Senate, leadership of (D-CA) congressional committees with jurisdiction over Tribal health has changed quite a bit. Below are the Chairs and Ranking Members Senate Committee on Appropriations of relevant committees and subcommittees Chairman: Sen. Daniel Inouye (D-HI) th Ranking Member: Sen. Thad Cochran (R-MS) for the 112 Congress: Subcommittee on Interior and the Environment House Committee on Appropriations Chairman: Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI) Chairman: Rep. Harold Rogers (R-KY) Ranking Member: Sen. Lisa Murkowski Ranking Member: Rep. Norm Dicks (D-WA) (R-AK) Subcommittee on Interior and the Environment Senate Committee on Finance Chairman: Rep. Mike Simpson (R-ID) Chairman: Sen. Max Baucus (D-MT) Ranking Member: Rep. Jim Moran (D-VA) Ranking Member: Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT) House Committee on Energy and Commerce Senate Committee on Health, Education, Chairman: Rep. Fred Upton (R-MI) Labor and Pensions (HELP) Ranking Member: Rep.