1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

37 Brook Street Raunds Northamptonshire NN9

37 Brook Street Prominent trading location in Raunds town centre 592 sq ft ground floor retailing with double frontage Raunds Available to let on new lease Northamptonshire NN9 6LL Gross Internal Area approx. 8,323 sqft (773.2 sqm) Raunds occupies a strategic location adjacent to the A45 dual BUSINESS RATES carriageway within East Northamptonshire, which connects Rateable value £6,100 * directly with Junctions 15, 15A and 16 of the M1 motorway, some 15 miles to the west and to the A14 (Thrapston Junction * In line with current Government legislation, if 12) some 7 miles to the east. occupied by a business as their sole commercial property, they will pay no rates. The subject premises is situated within the heart of the town centre, with nearby occupiers including the Post Office, QD Applicants are advised to verify the rating assessment with Stores, Jesters Café and Mace Convenience Store. the Local Authority. ACCOMMODATION SERVICES The property comprises an open plan ground floor retail unit We are advised that mains services are connected to the benefitting from a suspended ceiling with inset lighting. premises). None have been tested by the agent. Ground Floor LEGAL COSTS Sales Area 55.06 sq m 592 sq ft Each party to bear their own legal costs. wc The first floor is subject to a residential conversion, although in VIEWING the early stages of marketing maybe available to let with the To view and for further details please contact: ground floor accommodation. Samantha Jones Email: [email protected] TENURE The ground floor retail unit is being offered to let on a new Mobile: 07990 547366 effective full repairing and insuring lease, for a term to be agreed. -

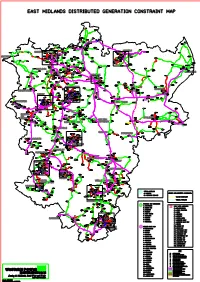

East Midlands Constraint Map-Default

EAST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP MISSON MISTERTON DANESHILL GENERATION NORTH WHEATLEY RETFOR ROAD SOLAR WEST GEN LOW FARM AD E BURTON MOAT HV FARM SOLAR DB TRUSTHORPE FARM TILN SOLAR GENERATION BAMBERS HALLCROFT FARM WIND RD GEN HVB HALFWAY RETFORD WORKSOP 1 HOLME CARR WEST WALKERS 33/11KV 33/11KV 29 ORDSALL RD WOOD SOLAR WESTHORPE FARM WEST END WORKSOPHVA FARM SOLAR KILTON RD CHECKERHOUSE GEN ECKINGTON LITTLE WOODBECK DB MORTON WRAGBY F16 F17 MANTON SOLAR FARM THE BRECK LINCOLN SOLAR FARM HATTON GAS CLOWNE CRAGGS SOUTH COMPRESSOR STAVELEY LANE CARLTON BUXTON EYAM CHESTERFIELD ALFORD WORKS WHITWELL NORTH SHEEPBRIDGE LEVERTON GREETWELL STAVELEY BATTERY SW STN 26ERIN STORAGE FISKERTON SOLAR ROAD BEVERCOTES ANDERSON FARM OXCROFT LANE 33KV CY SOLAR 23 LINCOLN SHEFFIELD ARKWRIGHT FARM 2 ROAD SOLAR CHAPEL ST ROBIN HOOD HX LINCOLN LEONARDS F20 WELBECK AX MAIN FISKERTON BUXTON SOLAR FARM RUSTON & LINCOLN LINCOLN BOLSOVER HORNSBY LOCAL MAIN NO4 QUEENS PARK 24 MOOR QUARY THORESBY TUXFORD 33/6.6KV LINCOLN BOLSOVER NO2 HORNCASTLE SOLAR WELBECK SOLAR FARM S/STN GOITSIDE ROBERT HYDE LODGE COLLERY BEEVOR SOLAR GEN STREET LINCOLN FARM MAIN NO1 SOLAR BUDBY DODDINGTON FLAGG CHESTERFIELD WALTON PARK WARSOP ROOKERY HINDLOW BAKEWELL COBB FARM LANE LINCOLN F15 SOLAR FARM EFW WINGERWORTH PAVING GRASSMOOR THORESBY ACREAGE WAY INGOLDMELLS SHIREBROOK LANE PC OLLERTON NORTH HYKEHAM BRANSTON SOUTH CS 16 SOLAR FARM SPILSBY MIDDLEMARSH WADDINGTON LITTLEWOOD SWINDERBY 33/11 KV BIWATER FARM PV CT CROFT END CLIPSTONE CARLTON ON SOLAR FARM TRENT WARTH -

192 Finedon Road Irthlingborough | Wellingborough

192 Finedon Road Irthlingborough | Wellingborough | Northamptonshire | NN9 5UB 192 FINEDON ROAD A beautifully presented detached family house with integral double garage set in half an acre located on the outskirts of Irthlingborough. The house is set well back from the road and is very private with high screen hedging all around, it is approached through double gates to a long gravelled driveway with beautifully maintained mature gardens to the side and rear, there is ample parking to the front leading to the garage. Internally the house has a flexible layout and is arranged over three floors with scope if required to create a separate guest annexe. On entering you immediately appreciate the feeling of light and space; there is a bright entrance hall with wide stairs to the upper and lower floors. On the right is a study and the large reception room which opens to the conservatory with access to a sun terrace, the conservatory leads through to a further conservatory currently used as a dining room. To the rear of the house is a family kitchen breakfast room which also opens to the conservatory/dining room. On the upper floor are the bedrooms, the master bedroom is a great size with a dressing area and an en-suite shower room. There are a further two double bedrooms and a smart family bathroom. On the lower floor is a good size utility room and a further double bedroom which opens to the large decked terrace and garden, there is also a further shower room and a separate guest cloakroom. -

Pre-Submission Draft East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2/ 2011-2031

Pre-Submission Draft East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2/ 2011-2031 Regulation 19 consultation, February 2021 Contents Page Foreword 9 1.0 Introduction 11 2.0 Area Portrait 27 3.0 Vision and Outcomes 38 4.0 Spatial Development Strategy 46 EN1: Spatial development strategy EN2: Settlement boundary criteria – urban areas EN3: Settlement boundary criteria – freestanding villages EN4: Settlement boundary criteria – ribbon developments EN5: Development on the periphery of settlements and rural exceptions housing EN6: Replacement dwellings in the open countryside 5.0 Natural Capital – environment, Green Infrastructure, energy, 66 sport and recreation EN7: Green Infrastructure corridors EN8: The Greenway EN9: Designation of Local Green Space East Northamptonshire Council Page 1 of 225 East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2: Pre-Submission Draft (February 2021) EN10: Enhancement and provision of open space EN11: Enhancement and provision of sport and recreation facilities 6.0 Social Capital – design, culture, heritage, tourism, health 85 and wellbeing, community infrastructure EN12: Health and wellbeing EN13: Design of Buildings/ Extensions EN14: Designated Heritage Assets EN15: Non-Designated Heritage Assets EN16: Tourism, cultural developments and tourist accommodation EN17: Land south of Chelveston Road, Higham Ferrers 7.0 Economic Prosperity – employment, economy, town 105 centres/ retail EN18: Commercial space to support economic growth EN19: Protected Employment Areas EN20: Relocation and/ or expansion of existing businesses EN21: Town -

Irchester (X46) Northamptonearls Bartonwellingborough Rushdenrushden Lakes (X47)Higham Raundsferrers

RaundsHigham RushdenFerrers RushdenIrchester Lakes (X47)Wellingborough (X46)Earls BartonNorthampton Mondays to Saturdays except public holidays X4 X47 X47 X46 X47 X46 X46 X46 X47 X46 X47 X46 X47 X46 X47 MF MF Sat Sch Raunds Square Marshalls Road 0548 0620 0643 0653 0715 0745 0820 0850 20 50 1320 Warth Park ASDA 0550 0622 0645 0655 0718 0748 0823 0853 23 53 1323 Stanwick Church Hall 0600 0633 0656 0706 0730 0800 0835 0905 35 05 1335 Chowns Mill Roundabout 0606 0639 0702 0712 0722 0736 0806 0841 0911 41 11 1341 Higham Ferrers Green Dragon 0546 0608 0642 0705 0714 0724 0739 0809 0844 0914 44 14 1344 Rushden Skinners Hill 0554 0616 0651 0714 0724 0734 0748 0818 0853 0923 53 23 1353 Rushden Grangeway x 0620 x 0720 0730 0740 x 0825 x 0929 x 29 x Rushden Waitrose 0559 B 0656 x x x 0753 x 0858 x 58 x 1358 Rushden Lakes arrive 0600 0627 0657 x x x 0755 x 0900 x 00 x until 1400 Rushden Lakes depart 0605 0628 0701 x x x 0804 x 0904 x 04 x 1404 Irchester Church x 0634 x x x x x x x x x x x Irchester opp Post Office x 0635 x 0727 0737 0747 x 0832 x 0936 x 36 x Wellingborough Church St stop C arrive 0619 0647 0719 0739 0749 0759 0822 0848 0922 0948 22 48 1422 Wellingborough Church St stop C depart 0549 0620 0649 0722 0743 0752 0803 0825 0855 0925 0955 25 55 1425 Great Doddington Square x 0631 x 0733 x x x 0836 x 0936 x 36 x 1436 Earls Barton Square 0602 0637 0709 0739 0803 0812 0823 0842 0915 0942 1015 42 15 1442 then at these mins past each hour Ecton Worlds End 0607 0641 0713 0743 0807 0816 0827 0848 0921 0948 1021 48 21 1448 Great Billing footbridge -

Northamptonshire Local Government Pensions Scheme Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 2009–2010

Northamptonshire Local Government Pensions Scheme Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 2009–2010 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE LOCAL GOVERNMENT PENSION SCHEME Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 2009–2010 Registered Pension Scheme Number: 00329946RE Contents Page Introduction 3 Management and Financial Performance Report Scheme management and advisers 4 Risk management 6 Scheme Framework 8 Funding Strategy Statement 9 Scheme Administration Report 10 Financial performance 12 Management performance 13 Investment Policy and Performance Report Benchmark April 2009 27 Fund Manager profile 28 Investment Review 2009–10 30 Investment Performance 2009–10 33 Performance by Asset Class 34 Local Authority Universe 34 Benchmark April 2010 36 Actuarial Reports Actuarial Report on the Fund 38 Actuarial Position Statement 39 Investment Return Assumptions 40 Governance Arrangements 41 Fund Account and Net Assets Statement 45/46 Notes to the Accounts 47 Auditors Report 57 Glossary 59 2 INTRODUCTION This Annual Report and Statement of Accounts sets out the arrangements by which the Local Government Pension Scheme operates, reports changes which have taken place and reviews the investment activity and performance of the Northamptonshire Fund during the year. The Statement of Accounts has been prepared in accordance with the Code of Practice for Local Authority Accounting in Great Britain and the Statement of Recommended Practice on Local Authority Accounting in the United Kingdom (Pension Scheme Accounts) (SORP) 2009. Mr D Lawrenson Assistant Chief Executive, -

Activities, Groups and Opportunities for 7-18 Year Olds in Raunds, Ringstead and Stanwick

2017 Activities, groups and opportunities for 7-18 year olds in Raunds, Ringstead and Stanwick RAUNDS YOUTH FORUM RAUNDS, RINGSTEAD & STANWICK (ACTIVITIES FOR 7-18 YEAR OLDS) ACTIVITIES & GROUPS DETAILS CONTACT AMATEUR DRAMATICS/MUSIC STAGS (Stanwick) Fridays. Age 8-16’s www.stanwickdramagroup.weebly.com Guitar teacher By appointment www.guitarteacherwellingborough.co.uk/gtw Piano & Vocal teacher By appointment www.beccyhurrell.co.uk/ ARCHERY Archers of Raunds Junior Section for Age 8-18s www.archersofraunds.co.uk CADETS Sea Cadets (Rushden Diamond Division) Tuesdays & Fridays. Age 10+ www.sea-cadets.org/rushdendiamond Air Cadets (858 Rushden Squadron) Mondays & Wednesdays. Age 13-18s www.858aircadets.org.uk Army Cadets (Raunds Manor School) Tuesdays 7:15pm – 9:15pm Age 12+ www.armycadets.com Navy Cadet Unit (TS Collingwood) Wednesdays. Age 7-18. Email: [email protected] CHILDREN'S CLUBS Kids' Club (Raunds Community Church) Fridays. School Years 1-4 www.raundscommunitychurch.org Raunds Rascals Breakfast & After school Week days before & after school upto 11yrs 01933 461097 [email protected] CHURCH Methodist Church, Raunds Sundays (all ages) Phone: (01933) 622137 Church of England Benefice Raunds, Ringstead, Hargrave and Stanwick www.4spires.org Family Service (St.Peters, Raunds) 2nd Sunday of every month. All ages. www.4spires.org/calendar Ultim8 (Raunds Community Church) Sundays. Age 5-16 www.raundscommunitychurch.org CHOIR St.Peter's Church Choir Friday evenings. 8+ www.4spires.org/groups-and-organisations CRICKET Raunds Cricket Club Check website for age groups www.raundstown.play-cricket.com DANCE Hayley Nadine Dance Various classes for all ages www.danceacademyshowcase.com LF Dance (Ballet, tap, street, modern) Wednesdays and Fridays. -

Agenda Item No: 2 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1972 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL 16 May 2013 I DO HEREBY CERTIFY and RETURN That

Agenda Item No: 2 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1972 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL 16 May 2013 I DO HEREBY CERTIFY AND RETURN that the names of the persons elected as COUNTY COUNCILLORS for the County of Northamptonshire are as follows:- Electoral Division Name and Address BOROUGH OF CORBY CORBY RURAL Stanley Joseph Heggs – Conservative 10 Grays Drive, Stanion, Kettering Northamptonshire, NN14 1DE CORBY WEST Julie Brookfield – Labour & Co-Operative 16 Wentworth Dr, Oundle, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, PE8 4QF KINGSWOOD John Adam McGhee – Labour & Co-Operative 15 Tavistock Square, Corby, Northamptonshire, NN18 8DA LLOYDS Bob Scott – Labour 6 Occupation Road, Corby, Northamptonshire, NN17 1EB OAKLEY Mary Butcher – Labour 7 Willets Close, Corby, Northamptonshire, NN17 1HU DISTRICT OF DAVENTRY BRAUNSTON & CRICK Steve Slatter – Conservative Acresfield, 28 Nutcote, Naseby, Northamptonshire, NN6 6DG BRIXWORTH Catherine Boardman – Conservative Lodge Farm, Welford, Northamptonshire, NN6 6JB DAVENTRY EAST Alan Hills - Conservative 25 The Fairway, Daventry, Northamptonshire, NN11 4NW DAVENTRY WEST Adam Collyer – UK Independence Party 23 Royal Start Drive, Daventry, Northamptonshire, NN11 9FZ LONG BUCKBY Steve Osborne – Conservative 14 High Street, Long Buckby, Northampton, NN6 7RD MOULTON Judith Shephard - Conservative Windbreck, Butchers Lane, Boughton, Northampton, NN2 8SL WOODFORD & WEEDON Robin Brown - Conservative 38 High Stack, Long Buckby, Northants Northamptonshire, NN6 7QT DISTRICT OF EAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE HIGHAM FERRERS Derek Charles Lawson -

Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Revocation of the East

Appendix A – SEA of the Revocation of the East Midlands Regional Strategy Appendix A Policies in the East Midlands Regional Strategy This Appendix sets out the text of the policies that make up the Regional Strategy for the East Midlands. It comprises policies contained in The East Midlands Regional Plan published in March 2009. The East Midlands Regional Plan POLICY 1: Regional Core Objectives To secure the delivery of sustainable development within the East Midlands, all strategies, plans and programmes having a spatial impact should meet the following core objectives: a) To ensure that the existing housing stock and new affordable and market housing address need and extend choice in all communities in the region. b) To reduce social exclusion through: • the regeneration of disadvantaged areas, • the reduction of inequalities in the location and distribution of employment, housing, health and other community facilities and services, and by; • responding positively to the diverse needs of different communities. c) To protect and enhance the environmental quality of urban and rural settlements to make them safe, attractive, clean and crime free places to live, work and invest in, through promoting: • ‘green infrastructure’; • enhancement of the ‘urban fringe’; • involvement of Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships; and • high quality design which reflects local distinctiveness. d) To improve the health and mental, physical and spiritual well being of the Region's residents through improvements in: • air quality; • ‘affordable warmth’; -

Nene Way Towns and Villages

Walk distances in Km © RNRP Cogenhoe to Great Doddington 6.5 km Alternatively: Cogenhoe to Earls Barton 4.7 km Earls Barton to Great Doddington 4.7 km Great Doddington to Little Irchester, Wellingborough 3.5 km Little Irchester to Higham Ferrers 7.5 km Higham Ferrers to Irthlingborough 3.3 km All distances are approximate Key of Services Pub Telephone Nene Way Towns and Villages Church Toilets Rivers and Forests and Streams Woodland Post Office Places of Roads Lakes and Historical Interest Reservoirs National Cycle Chemist Park Motorways Network Route 6 Nene Way Shopping Parking A ‘A’ Roads Regional Route 71 This Information can be provided in other languages and formats upon Cogenhoe to Irthlingborough request, such as large Print, Braille and CD. Contact 01604 236236 Transport & Highways, Northamptonshire County Council, 22.3kms/13.8miles Riverside House, Bedford Road, Northampton NN1 5NX. Earls Barton village extra 2.8kms/1.7miles Telephone: 01604 236236. Email: [email protected] For more information on where to stay and sightseeing please visit www.letyourselfgrow.com This leaflet was part funded by the Aggregates Levy Sustainability Fund, for more information please visit www.naturalengland.org.uk Thanks to RNRP for use of photography www.riverneneregionalpark.org All photographs copyright © of Northamptonshire County Council unless stated. Published March 2010 enture into the village of Cogenhoe, which is to enjoy a picnic of the locally produced foods you Vpronounced “Cook-noe” and is situated on bought from the shopping yard. This area is also a high ground overlooking the Nene Valley. While in canoe launch point giving access to the River Nene Cogenhoe, make sure you make time to explore St and the Nene Way footpath. -

Rushden Lakes Bus Guide

getting here by bus rushdenlakes.com AS01810 RL Stagecoach Timetable Ad.indd 1 22/05/2017 12:51 rushdenlakes.com FASHION GETS A BREATH OF FRESH AIR. Find inspiration at Northamptonshire’s newest shopping and leisure destination. welcome travelling Rushden Lakes is a shopping and leisure from destination unlike anywhere else. It’s all set in route approx page an area of outstanding natural beauty beside number journey time number picturesque lakes. 49 55 mins Barton Seagrave 10 Leisurely walks, wildlife discovery and family 50 26 mins fun exist alongside familiar high-street fashion favourites, department stores and an Bedford 50 57 mins 12 impressive line-up of lake-side restaurants 49 49 mins and cafes. Rushden Lakes offers it all. Burton Latimer 14 50 19 mins Throughout this guide you’ll find details of Earls Barton X46 X47 37 mins 16 how to get to Rushden Lakes by bus. 49 45 mins Finedon 18 Opposite is a list of locations running direct; 50 17 mins choose where you live and go to the relevant 49 26 mins page. You’ll find maps, fares and departure Higham Ferrers 20 times. X46 X47 16mins 49 38 mins Irthlingborough 22 Getting to Rushden Lakes is easy by bus 50 10 mins 49 1hr 11 mins Kettering 24 Enjoy your 50 37 mins journey Northampton X46 X47 1hr 15mins 26 Raunds X46 X47 40 mins 28 49 18 mins Rushden 50 9 mins 30 X46 X47 7 mins Wellingborough X46 X47 18 mins 32 4 5 Rockingham Rd Rockingham A43 Rothwell Rd Stamford Rd Kettering General Kettering Hospital Tresham College Kettering Rd Kettering Powell Ln Powell Barton A14 Seagrave Northampton Rd Finedon Burton route Latimer A6 map Irthlingborough getting to Rushden Lakes travelling from further a-field? use our journey planner at www.stagecoachbus.com or with the stagecoachbus app Sharnbrook d R in a M 6 7 travelling most days to Rushden Lakes 00 travelling from Wellingborough, 50 travelling from Corby, Kettering, £21. -

Cogenhoe to Irthlingborough Request, Such As Large Print, Braille and CD

Walk distances in Km © RNRP Cogenhoe to Great Doddington 6.5 km Alternatively: Cogenhoe to Earls Barton 4.7 km Earls Barton to Great Doddington 4.7 km Great Doddington to Little Irchester, Wellingborough 3.5 km Little Irchester to Higham Ferrers 7.5 km Higham Ferrers to Irthlingborough 3.3 km All distances are approximate Key of Services Pub Telephone Nene Way Towns and Villages Church Toilets Rivers and Forests and Streams Woodland Post Office Places of Roads Lakes and Historical Interest Reservoirs National Cycle Chemist Park Motorways Network Route 6 Nene Way Shopping Parking A ‘A’ Roads Regional Route 71 This Information can be provided in other languages and formats upon Cogenhoe to Irthlingborough request, such as large Print, Braille and CD. Contact 01604 236236 Transport & Highways, Northamptonshire County Council, 22.3kms/13.8miles Riverside House, Bedford Road, Northampton NN1 5NX. Earls Barton village extra 2.8kms/1.7miles Telephone: 01604 236236. Email: [email protected] For more information on where to stay and sightseeing please visit www.letyourselfgrow.com This leaflet was part funded by the Aggregates Levy Sustainability Fund, for more information please visit www.naturalengland.org.uk Thanks to RNRP for use of photography www.riverneneregionalpark.org All photographs copyright © of Northamptonshire County Council unless stated. Published March 2010 enture into the village of Cogenhoe, which is to enjoy a picnic of the locally produced foods you Vpronounced “Cook-noe” and is situated on bought from the shopping yard. This area is also a high ground overlooking the Nene Valley. While in canoe launch point giving access to the River Nene Cogenhoe, make sure you make time to explore St and the Nene Way footpath.