Themes in Art & Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equipo Crónica

Equipo Crónica Tomàs Llorens 1 This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao © Equipo Crónica (Manuel Valdés), VEGAP, Bilbao, 2015 Photography credits © Archivo Fotográfico Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Alicante, MACA: fig. 9 © Archivo Fotográfico Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía: figs. 11, 12 © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa-Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 15, 20 © Colección Arango: fig. 18 © Colección Guillermo Caballero de Luján: figs. 4, 7, 10, 16 © Fundación “la Caixa”. Gasull fotografía: fig. 8 © Patrimonio histórico-artístico del Senado: fig. 19 © Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast - ARTOTHEK: fig. 14 Original text published in the catalogue Equipo Crónica held at the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (10 February to 18 May 2015). Sponsored by: 2 1 Estampa Popular de Valencia and the beginnings of Equipo Crónica Founded in 1964, Equipo Crónica and Estampa Popular de Valencia presented themselves to the public as two branches of a single project. Essentially, however, they were two different, independent ones and either could have appeared and evolved without the other. -

Visit Oma's Forest, Santimamiñe's Cave, Bermeo, Mundaka and Gernika!

www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com Visit Oma’s Forest, Santimamiñe’s cave, Bermeo, Mundaka and Gernika! All day trip Bilbao Akelarre Hostel c/ Morgan 4-6, 48014 Bilbao (Bizkaia) - Teléfono: (+34) 94 405 77 13 - [email protected] - www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com - Leaving Bilbao Akelarre Hostel • Arriving to the “enchanted” forest of Oma Forest of Oma Located at 8 kilometers of Guernika and right in the middle of the Uradaibai biosphere reserve , The Oma forest offers to its visitors an image between art and mystery thanks to the piece of art of Agustín Ibarrola . 20 years ago, this Basque artist had the idea of giving life to the trees by painting them. That way, in a narrow and large valley, away from the civilisation and its noise, you can find a mixture of colours, figures and symbols that can make you feel all sorts of different sensations. Without any established rout, the visitor himself will have to find out their own vision of the forest. Bilbao Akelarre Hostel c/ Morgan 4-6, 48014 Bilbao (Bizkaia) - Teléfono: (+34) 94 405 77 13 - [email protected] - www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com Bilbao Akelarre Hostel c/ Morgan 4-6, 48014 Bilbao (Bizkaia) - Teléfono: (+34) 94 405 77 13 - [email protected] - www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com - Leaving Oma’s Forest • Arriving at Santimamiñe’s cave Santimamiñe’s Cave Located in the Biscay town of Kortezubi and figuring in the list of the Human Patrimony, Santimamiñe’s Cave represents one of the principle prehistorically site of Biscay. They have found in it remains and cave paintings who age back from the Palaeolithic Superior in the period of “Magdaleniense”. -

Bombing of Gernika

BIBLIOTECA DE The Bombing CULTURA VASCA of Gernika The episode of Guernica, with all that it The Bombing ... represents both in the military and the G) :c moral order, seems destined to pass 0 of Gernika into History as a symbol. A symbol of >< many things, but chiefly of that Xabier lruio capacity for falsehood possessed by the new Machiavellism which threatens destruction to all the ethical hypotheses of civilization. A clear example of the ..e use which can be made of untruth to ·-...c: degrade the minds of those whom one G) wishes to convince. c., '+- 0 (Foreign Wings over the Basque Country, 1937) C> C: ISBN 978-0-9967810-7-7 :c 90000 E 0 co G) .c 9 780996 781077 t- EDITORIALVASCA EKIN ARGITALETXEA Aberri Bilduma Collection, 11 Ekin Aberri Bilduma Collection, 11 Xabier Irujo The Bombing of Gernika Ekin Buenos Aires 2021 Aberri Bilduma Collection, 11 Editorial Vasca Ekin Argitaletxea Lizarrenea C./ México 1880 Buenos Aires, CP. 1200 Argentina Web: http://editorialvascaekin- ekinargitaletxea.blogspot.com Copyright © 2021 Ekin All rights reserved First edition. First print Printed in America Cover design © 2021 JSM ISBN first edition: 978-0-9967810-7-7 Table of Contents Bombardment. Description and types 9 Prehistory of terror bombing 13 Coup d'etat: Mussolini, Hitler, and Franco 17 Non-Intervention Committee 21 The Basque Country in 1936 27 The Basque front in the spring of 1937 31 Everyday routine: “Clear day means bombs” 33 Slow advance toward Bilbao 37 “Target Gernika” 41 Seven main reasons for choosing Gernika as a target 47 The alarm systems and the antiaircraft shelters 51 Typology and number of airplanes and bombs 55 Strategy of the attack 59 Excerpts from personal testimonies 71 Material destruction and death toll 85 The news 101 The lie 125 Denial and reductionism 131 Reconstruction 133 Bibliography 137 I can’t -it is impossible for me to give any picture of that indescribable tragedy. -

A Monthly E-Newsletter for the Latest in Cultural Management and Policy ISSUE N° 114

news A monthly e-newsletter for the latest in cultural management and policy ISSUE N° 114 DIGEST VERSION FOR OUR FOLLOWERS Issue N°104 / news from encatc / Page 1 CONTENTS NOTE FROM THE Issue N°114 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR EDITOR 2 Dear colleagues, Welcome to the new re-vamped online ENCATC resources to make it ENCATC NEWS 3 version of our monthly ENCATC easier to access direct sources and newsletter! material for your work! Finally, for those who liked the PDF just as it was, These last two months we took the UPCOMING you can still find all the information time to have a critical look at this very 10 you trust from ENCATC and can print EVENTS product we have been producing for this publication to take with you! you for over 20 years as well as to CALLS & ask the opinions of members, key The new format of the ENCATC stakeholders, and loyal readers in newsletter will also offer more space OPPORTUNITIES 13 order to find the new way to adapt this for contributions from our members information tool to reading practices and stakeholders. In this issue you will EUROPEAN YEAR and the digital environment. enjoy articles written by our members Lidia Varbanova, Claire Giraud-Labalte OF CULTURAL 14 So what is the next stage for ENCATC and Savina Tarsitano and from the HERITAGE 2018 News? Many said they were plagued network Future for Religious Heritage. by information overload and felt pressure to have updates quickly and Finally, to mark the European Year of ENCATC IN only a click away. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

The Basque Refugee Children of the Spanish Civil War in the Uk 177

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES THE BASQUE REFUGEE CHILDREN OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR IN THE UK: MEMORY AND MEMORIALISATION by Susana Sabín-Fernández Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2010 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Doctor of Philosophy THE BASQUE REFUGEE CHILDREN OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR IN THE UK: MEMORY AND MEMORIALISATION By Susana Sabín-Fernández A vast body of knowledge has been produced in the field of war remembrance, particularly concerning the Spanish Civil War. However, the representation and interpretation of that conflictual past have been increasingly contested within the wider context of ‘recuperation of historical memory’ which is taking place both in Spain and elsewhere. -

Basques in the Americas from 1492 To1892: a Chronology

Basques in the Americas From 1492 to1892: A Chronology “Spanish Conquistador” by Frederic Remington Stephen T. Bass Most Recent Addendum: May 2010 FOREWORD The Basques have been a successful minority for centuries, keeping their unique culture, physiology and language alive and distinct longer than any other Western European population. In addition, outside of the Basque homeland, their efforts in the development of the New World were instrumental in helping make the U.S., Mexico, Central and South America what they are today. Most history books, however, have generally referred to these early Basque adventurers either as Spanish or French. Rarely was the term “Basque” used to identify these pioneers. Recently, interested scholars have been much more definitive in their descriptions of the origins of these Argonauts. They have identified Basque fishermen, sailors, explorers, soldiers of fortune, settlers, clergymen, frontiersmen and politicians who were involved in the discovery and development of the Americas from before Columbus’ first voyage through colonization and beyond. This also includes generations of men and women of Basque descent born in these new lands. As examples, we now know that the first map to ever show the Americas was drawn by a Basque and that the first Thanksgiving meal shared in what was to become the United States was actually done so by Basques 25 years before the Pilgrims. We also now recognize that many familiar cities and features in the New World were named by early Basques. These facts and others are shared on the following pages in a chronological review of some, but by no means all, of the involvement and accomplishments of Basques in the exploration, development and settlement of the Americas. -

Montmartre the Tour: La Place Des Abbesses (The Abbesses Square), the Small Streets, La Place Du Tertre (The Tertre Square), Le Sacré-Coeur (The Sacred Heart)

MONTMARTRE THE TOUR: LA PLACE DES ABBESSES (THE ABBESSES SQUARE), THE SMALL STREETS, LA PLACE DU TERTRE (THE TERTRE SQUARE), LE SACRÉ-COEUR (THE SACRED HEART) LE SACRÉ-COEUR THE SMALL STREETS LA PLACE DU TERTRE LES ABBESSES Lenght: Means of locomotion: on foot - 3H00 walking, Access for persons with reduced - half a day: walking + visit of the mobility : no Sacré-Coeur, Total distance: 4km - the entire day: walking + visit of Starting point: Place des Abbesses the Sacré-Coeur, the Montmartre (metro line 12, Abbesses station, museum and the Dali area. or the Montmartrobus Abbesses station) Public: All restaurant, « Le Relais de la Butte » (The Mound Inn), once called « Chez Azon » (At Azon’s). At the beginning of the 20th century, Father Azon gladly welcomed and fed all the penniless artists from the bateau- lavoir who paid him with works of art... which did not prevent him from Take rue des Abbesses going bankrupt ! (Abbesses Street) on your right and keep going forward for about 50 Climb the steps of this Emile metres. Goudeau small square (ex Ravignan Square). It is the same quietness At the Abbesses passage entrance, impression that we found in the on your right, graffities, drawings, Place des Abbesses, with benches, stencils and other inlays are trees, the big Wallace fountain, and animating the walls. some funny graffities. Pay close attention, you will have the opportunity to see many others On your left, with your back turned throughout the walk. to the steps, stands a recently cleaned building with white blinds Carry on and take rue Ravignan and green doors is the famous (Ravignan Street) on your right. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

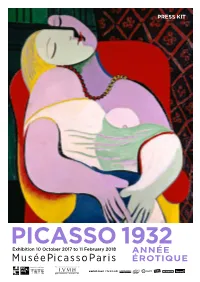

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

3"T *T CONVERSATIONS with the MASTER: PICASSO's DIALOGUES

3"t *t #8t CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MASTER: PICASSO'S DIALOGUES WITH VELAZQUEZ THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Joan C. McKinzey, B.F.A., M.F.A. Denton, Texas August 1997 N VM*B McKinzey, Joan C., Conversations with the master: Picasso's dialogues with Velazquez. Master of Arts (Art History), August 1997,177 pp., 112 illustrations, 63 titles. This thesis investigates the significance of Pablo Picasso's lifelong appropriation of formal elements from paintings by Diego Velazquez. Selected paintings and drawings by Picasso are examined and shown to refer to works by the seventeenth-century Spanish master. Throughout his career Picasso was influenced by Velazquez, as is demonstrated by analysis of works from the Blue and Rose periods, portraits of his children, wives and mistresses, and the musketeers of his last years. Picasso's masterwork of High Analytical Cubism, Man with a Pipe (Fort Worth, Texas, Kimbell Art Museum), is shown to contain references to Velazquez's masterpiece Las Meninas (Madrid, Prado). 3"t *t #8t CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MASTER: PICASSO'S DIALOGUES WITH VELAZQUEZ THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Joan C. McKinzey, B.F.A., M.F.A. Denton, Texas August 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to acknowledge Kurt Bakken for his artist's eye and for his kind permission to develop his original insight into a thesis. -

Pablo Picasso

Famous Artists In thirty seconds, tell your partner the names of as many famous artists as you can think of. 30stop Pablo Picasso th ArePablo you Picasso named was after born aon family 25 October member 1881. or someone special? He was born in Malaga in Spain. Did You Know? Picasso’s full surname was Ruiz y Picasso. ThisHis full follows name thewas SpanishPablo Diego custom José Franciscowhere people de havePaula two Juan surnames. Nepomuceno The María first de is losthe Remedios first part ofCipriano their dad’sde la Santísimasurname, Trinidad the second Ruiz isy thePicasso. first He was named after family members and special partreligious of their figures mum’s known surname. as saints. Talk About It Picasso’s Early Life Do you know what your first word was? Words like ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ are common first words. However, Picasso’s mum said his first word was ‘piz’, short for ‘lapiz’, the Spanish word for pencil. Cubism Along with an artist called Georges Braque, Picasso started a new style of art called Cubism. Cubism is a style of art which aims to show objects and people from lots of different angles all at one time. This is done through the use of cubes and other shapes. Here are some examples of Picasso’s cubist paintings. What do you think about each of these paintings? Talk About It DanielWeeping-HenryMa Jolie, Woman,Kahnweiler, 1912 1937 1910 Picasso’s Different Styles ThroughoutHow do these his paintings life, Picasso’s make artyou took feel? on differentHow do you styles. think Picasso was feeling when he painted them? One of the most well known of these phases was known as his ‘blue period’.