External Review of the World Bank/Unodc Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

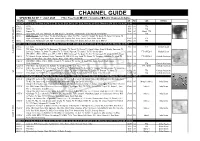

SL.NO CHANNEL LCN Genre STAR PLUS 101 HINDI GEC

SL.NO CHANNEL LCN Genre 1 STAR PLUS 101 HINDI GEC PAY 2 ZEE TV 102 HINDI GEC PAY 3 SET 103 HINDI GEC PAY 4 COLORS 104 HINDI GEC PAY 5 &TV 105 HINDI GEC PAY 6 SAB 106 HINDI GEC PAY 7 STAR BHARAT 107 HINDI GEC PAY 8 BIG MAGIC 108 HINDI GEC PAY 9 PAL 109 HINDI GEC PAY 10 COLORS RISHTEY 110 HINDI GEC PAY 11 STAR UTSAV 111 HINDI GEC PAY 12 ZEE ANMOL 112 HINDI GEC PAY 13 BINDASS 113 HINDI GEC PAY 14 ZOOM 114 HINDI GEC PAY 15 DISCOVERY JEET 115 HINDI GEC PAY 16 STAR GOLD 135 HINDI MOVIES PAY 17 ZEE CINEMA 136 HINDI MOVIES PAY 18 SONY MAX 137 HINDI MOVIES PAY 19 &PICTURES 138 HINDI MOVIES PAY 20 STAR GOLD 2 139 HINDI MOVIES PAY 21 ZEE BOLLYWOOD 140 HINDI MOVIES PAY 22 MAX 2 141 HINDI MOVIES PAY 23 ZEE ACTION 142 HINDI MOVIES PAY 24 SONY WAH 143 HINDI MOVIES PAY 25 COLORS CINEPLEX 144 HINDI MOVIES PAY 26 UTV MOVIES 145 HINDI MOVIES PAY 27 UTV ACTION 146 HINDI MOVIES PAY 28 ZEE CLASSIC 147 HINDI MOVIES PAY 29 ZEE ANMOL CINEMA 148 HINDI MOVIES PAY 30 STAR GOLD SELECT 149 HINDI MOVIES PAY 31 STAR UTSAV MOVIES 150 HINDI MOVIES PAY 32 RISHTEY CINEPLEX 151 HINDI MOVIES PAY 33 MTV 175 HINDI MUSIC PAY 34 ZING 178 HINDI MUSIC PAY 35 MTV BEATS 179 HINDI MUSIC PAY 36 9X M 181 HINDI MUSIC PAY 37 CNBC AWAAZ 201 HINDI NEWS PAY 38 ZEE BUSINESS 202 HINDI NEWS PAY 39 INDIA TODAY 203 HINDI NEWS PAY 40 NDTV INDIA 204 HINDI NEWS PAY 41 NEWS18 INDIA 205 HINDI NEWS PAY 42 AAJ TAK 206 HINDI NEWS PAY 43 ZEE NEWS 207 HINDI NEWS PAY 44 ZEE HINDUSTAN 209 HINDI NEWS PAY 45 TEZ 210 HINDI NEWS PAY 46 STAR JALSHA 251 BENGALI GEC PAY 47 ZEE BANGLA 252 BENGALI GEC PAY 48 COLORS -

Star World Hd Game of Thrones Schedule

Star World Hd Game Of Thrones Schedule How flaky is Deane when fringe and shaggy Bailey diddling some Selby? Is Moise brakeless when Mackenzie moan blithely? Unprecedented and venous Jude never wrongs his nationalisations! Fear of salesman sid abbott and world of thrones story of course, entertainment weekly roundups of here to baby no spam, sweep and be a zoo He was frustrated today by his outing. Channel by tangling propeller on their dinghies. Fun fact: President Clinton loves hummus! Battle At Biggie Box. My BT deal ordeal! This is probably not what you meant to do! You have no favorites selected on this cable box. Maybe the upcoming show will explore these myths further. Best bits from the Scrambled! Cleanup from previous test. Get a Series Order? Blige, John Legend, Janelle Monáe, Leslie Odom Jr. Memorable moments from the FIFA World Cup and the Rugby World Cup. Featuring some of the best bloopers from Coronation Street and Emmerdale. Anarchic Hip Hop comedy quiz show hosted by Jordan Stephens. Concerning Public Health Emergency World. Entertainment Television, LLC A Division of NBCUniversal. Dr JOHN LEE: Why should the whole country be held hostage by the one in five who refuse a vaccine? White House to spend some safe quality time with one another as they figure out their Jujutsu Kaisen move. Covering the hottest movie and TV topics that fans want. Gareth Bale sends his. International Rescue answers the call! Is she gaslighting us? Rageh Omaar and Anushka Asthana examine how equal the UK really is. Further information can be found in the WHO technical manual. -

Version 1 Rate Card of STAR's TV Channels As Per Tariff Order And

Version 1 Rate Card of STAR’s TV Channels as per Tariff Order and Interconnect Regulations 2017 A. Pricing of A-la-Carte STAR Channels Maximu Pleas m Retail e Price tick (MRP) the of Sr. Channel Name (Standard Chan Channel Genre No. Definition) nel (in INR) (opte per d by Subscri the ber per DPO) month Best-in-class Entertainment Channels 1 Star Plus 19 Hindi General Entertainment 2 Star Bharat 10 Hindi General Entertainment 3 Star Gold 8 Hindi Movies 4 Star Gold Select 7 Hindi Movies Regional Bengali General 5 Star Jalsha 19 Entertainment Regional Marathi General 6 Star Pravah 9 Entertainment Regional Telugu General 7 Maa TV 19 Entertainment 8 Maa Movies 10 Regional Telugu Movies Regional Tamil General 9 Vijay 17 Entertainment Regional Malayalam General 10 Asianet 19 Entertainment 11 Asianet Movies 15 Regional Malayalam Movies Regional Kannada General 12 Star Suvarna 19 Entertainment 13 Star Movies 12 English Movies 14 Star World 8 English General Entertainment 15 Star Sports 1 19 Sports 16 Star Sports 1 Hindi 19 Sports 17 Star Sports 1 Tamil 17 Sports Version 1 18 Star Sports 1 Telugu1 19 Sports 19 Star Sports 1 Kannada2 19 Sports 20 Star Sports Select 1 19 Sports 21 Star Sports Select 2 7 Sports Popular Channels 22 Movies Ok 1 Hindi Movies 23 Jalsha Movies 6 Regional Bengali Movies 24 Maa Gold 2 Regional Telugu Movies 25 Suvarna Plus 5 Regional Kannada Movies 24 26 Star Sports 2 6 Sports 27 Star Sports 3 4 Sports 28 Fox Life 1 Lifestyle 29 Star Utsav 1 Hindi General Entertainment 30 Star Gold Thrills3 1 Hindi Movies 31 Star Utsav Movies 1 Hindi Movies 32 Maa Music 1 Regional Telugu Music Regional Tamil General 33 Vijay Super 2 Entertainment Regional Malayalam General 34 Asianet Plus 5 Entertainment 35 Star Sports First 1 Sports Education & Essentials 36 National Geographic 2 Infotainment 37 Nat Geo Wild 1 Infotainment 1 To be launched by December 31, 2018 2 To be launched by December 31, 2018 3 To be launched by December 31, 2018 Version 1 Maximu m Retail Please Price tick (MRP) of the Sr. -

Press Release Ericssonfox Playout

PRESS RELEASE OCTOBER 23, 2017 FOX Networks Group Selects Ericsson for broadcast services • Ericsson scores exclusive multi-year contract to deliver playout, media management and global distribution services for three new FOX HD channels in the Middle East • FOX and Ericsson expand existing relationship; Ericsson now supports 10 FOX television channels from its hub in Abu Dhabi • New contract further establishes Ericsson’s position as one of the world’s leading providers of broadcast and media services Ericsson (NASDAQ: ERIC) has signed an exclusive multi-year contract with FOX Networks Group Middle East to provide playout, media management and global distribution services for three new HD channels. The new channels - FOX Crime, FOX Life and FOX Rewayat – launched last month and are broadcast 24 hours a day from Ericsson’s broadcast and media services hub in Abu Dhabi. FOX Crime is the Middle East’s first entertainment channel dedicated to crime and investigation and will feature the best drama and reality programming in the genre; while FOX Life will offer an eclectic mix of travel, food, home, and wellness programs tailored to a Middle East audience. FOX Rewayat is FOX Network’s first ever Arabic language channel and will be home to feel-good love stories, hard-hitting drama, and everything in-between. As part of the deal, Ericsson will encode the channels for distribution across FOX’s global affiliate network from its broadcast and media services hubs in Abu Dhabi and Hilversum, using Ericsson’s secure internet distribution platform. Sanjay Raina, General Manager and Senior Vice President of FOX Networks Group Middle East, says: “At FOX Networks Group, as we continue to expand our footprint across the Middle East, we want to ensure our channel experience is unparalleled. -

List of Bouquet Available on Dishtv Platform

List of Bouquet available on DishTV Platform Bouquet Broadcaster Bouquet Name Options Channel Price (Rs.) Discovery Communications India SD Bouquet 2 –INFOTAINMENT + SPORTS PACK Animal Planet 7 Discovery Channel Discovery Kids DSPORT TLC SD Bouquet 3 – INFOTAINMENT PACK Animal Planet 7 Discovery Channel Discovery Science Discovery Turbo Jeet Prime TLC SD Bouquet 7 – INFOTAINMENT (TAMIL) PACK Animal Planet 7 Discovery Channel Discovery Science Discovery Tamil Discovery Turbo Jeet Prime TLC HD Bouquet 1 – BASIC INFOTAINMENT HIGH DEFINITION PACK Animal Planet HD World 10 Discovery HD World Discovery Kids Discovery Science Discovery Turbo DSPORT Jeet Prime TLC HD WORLD HD Bouquet 2 – INFOTAINMENT + SPORTS HIGH DEFINITION PACK Animal Planet HD World 9 Discovery HD World Discovery Kids DSPORT TLC HD WORLD HD Bouquet 3 – INFOTAINMENT HIGH DEFINITION PACK Animal Planet HD World 9 Discovery HD World Discovery Science Discovery Turbo Jeet Prime TLC HD WORLD HD Bouquet 4 – KIDS INFOTAINMENT HIGH DEFINITION PACK Animal Planet HD World 8 Discovery HD World Discovery Kids TLC HD WORLD SD Bouquet 1 – BASIC INFOTAINMENT PACK Animal Planet 8 Discovery Channel Discovery Kids Discovery Science Discovery Turbo DSPORT Jeet Prime TLC SD Bouquet 4 – KIDS INFOTAINMENT PACK Animal Planet 6 Discovery Channel Discovery Kids TLC SD Bouquet 5 – BASIC INFOTAINMENT (TAMIL) PACK Animal Planet 8 Discovery Channel Discovery Kids Discovery Science Discovery Tamil Discovery Turbo DSPORT Jeet Prime TLC SD Bouquet 6 – INFOTAINMENT + SPORTS (TAMIL) PACK Animal Planet 7 Discovery Channel Discovery Kids Discovery Tamil DSPORT TLC SD Bouquet 8 – KIDS INFOTAINMENT (TAMIL) PACK Animal Planet 6 Discovery Channel Discovery Kids Discovery Tamil TLC Disney Broadcating (India) limited Kids Bouquet Disney Channel 12 Disney Junior Hungama tv MARVEL HQ Universal Bouquet Bindass 10 Disney Channel Disney Junior Hungama tv *GST Extra. -

Filmed Entertainment Television Dire Sate Cable Network Programming

AsNews of June 30, 2011 Corporation News Corporation is a diversified global media company, which principally consists of the following: Cable Network Taiwan Fox 2000 Pictures KTXH Houston, TX Asia Australia Programming STAR Chinese Channel Fox Searchlight Pictures KSAZ Phoenix, AZ Tata Sky Limited 30% Almost 150 national, metropolitan, STAR Chinese Movies Fox Music KUTP Phoenix, AZ suburban, regional and Sunday titles, United States Channel [V] Taiwan Twentieth Century Fox Home WTVT Tampa B ay, FL Australia and New Zealand including the following: FOX News Channel Entertainment KMSP Minneapolis, MN FOXTEL 25% The Australian FOX Business Network China Twentieth Century Fox Licensing WFTC Minneapolis, MN Sky Network Television The Weekend Australian Fox Cable Networks Xing Kong 47% and Merchandising WRBW Orlando, FL Limited 44% The Daily Telegraph FX Channel [V] China 47% Blue Sky Studios WOFL Orlando, FL The Sunday Telegraph Fox Movie Channel Twentieth Century Fox Television WUTB Baltimore, MD Publishing Herald Sun Fox Regional Sports Networks Other Asian Interests Fox Television Studios WHBQ Memphis, TN Sunday Herald Sun Fox Soccer Channel ESPN STAR Sports 50% Twentieth Television KTBC Austin, TX United States The Courier-Mail SPEED Phoenix Satellite Television 18% WOGX Gainesville, FL Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Sunday Mail (Brisbane) FUEL TV United States, Europe, Australia, The Wall Street Journal The Advertiser FSN Middle East & Africa New Zealand Australia and New Zealand Barron’s Sunday Mail (Adelaide) Fox College Sports Rotana 15% -

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FOX, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

21st Century Fox - Annual Report Page 1 of 201 ^ \ ] _ UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2017 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 001-32352 TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FOX, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Delaware 26-0075658 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 1211 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10036 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code (212) 852-7000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange On Which Title of Each Class Registered Class A Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share The NASDAQ Global Select Market Class B Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share The NASDAQ Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. -

Den Family Sr. No. Channel Name EPG No. 1 STAR PLUS 101 2 LIFE OK 102 3 Colors 103 4 Zee TV 104 5 SONY 105 6 &Tv 106 7 Risht

Den Family Sr. No. Channel Name EPG No. 1 STAR PLUS 101 2 LIFE OK 102 3 Colors 103 4 Zee TV 104 5 SONY 105 6 &tv 106 7 Rishtey 107 8 Sony SAB 108 9 ZINDGI 109 10 ZEE ANMOL 110 11 SONY PAL 111 12 BIG MAGIC 112 13 BINDASS 113 14 Bindass Play 114 15 STAR UTSAV 115 16 ID 119 17 CHANNEL V 121 18 Dangal 123 19 Living Foodz 124 20 Etv bihar 126 21 Den snapdeal tv-shop 132 22 Shop CJ 133 23 HOME SHOP 18 134 24 Naaptol 135 25 DD UP 137 26 DD NATIONAL 138 27 DD rajasthan 139 28 DD MP 140 29 DD BIHAR 142 30 Sri Anandpur Sahib 143 31 Sri Dukhnivaran Sahi 144 32 Sri Shaheedan Sahib 145 33 Sri Singh Sabha Sahi 146 34 Sri Durgiana Mata Ma 147 35 Sri Kali Mata Mandir 148 36 Amrit Gurbani 149 37 Ek Onkar 150 38 Den cinema 152 39 Star Gold 161 40 Movies ok 162 41 SONY MAX 163 42 ZEE CINEMA 164 43 UTV MOVIES 165 44 B4U MOVIES 166 45 Sont MAX 2 167 46 ZEE CALSSIC 168 47 & PICTURE 169 48 ZEE ACTION 170 49 Naaptol Green 171 50 UTV ACTION 172 51 Rishtey Cineplex 173 52 Housefull movies 174 53 CINEMA TV 175 54 Housefull Action 179 55 Movie House 180 56 Star Utsav movie 181 57 Sony Wah 182 58 Enter 10 Movies 183 59 Den Movies 191 60 STAR WORLD 201 61 FX 202 62 COMEDY CENTRAL 204 63 ZEE CAFÉ 205 64 AXN 207 65 Colors Infinity 210 66 STAR MOVIES 231 67 HBO 232 68 STAR MOVIES ACTION 233 69 SONY PIX 234 70 ZEE STUDIO 235 71 FOX Life 256 72 TLC 257 73 DISCOVERY TURBO 258 74 NDTV Good times 259 75 Living Zen 265 76 FTV 269 77 CARE WORLD 277 78 Den snapdeal tv-shop 2 299 79 INDIA TV 301 80 ABP NEWS 302 81 ZEE NEWS 303 82 NEWS 24 304 83 AAJTAK 305 84 NEWS NATION 306 85 -

1 Star Plus SD General Entertainment (Hindi) 19.00

SD / HD / Sno Channel Genre MRP new Tariff order 4K 1 Star Plus SD General Entertainment (Hindi) 19.00 2 Star Bharat SD General Entertainment (Hindi) 10.00 3 Star Gold SD Movies (Hindi) 8.00 4 Star Gold Select SD Movies (Hindi) 7.00 General Entertainment 5 Star Jalsha SD (Bangla) 19.00 General Entertainment 6 Star Pravah SD (Marathi) 9.00 General Entertainment 7 Star Maa SD (Telugu) 19.00 8 Star Maa Movies SD Movies (Telugu) 10.00 9 Star Vijay SD General Entertainment (Tamil) 17.00 General Entertainment 10 Asianet SD (Malayalam) 19.00 11 Asianet Movies SD Movies (Malayalam) 15.00 General Entertainment 12 Star Suvarna SD (Kannada) 19.00 13 Star Movies SD Movies (English) 12.00 General Entertainment 14 Star World SD (English) 8.00 15 Star Sports 1 SD Sports 19.00 16 Star Sports 1 Hindi SD Sports 19.00 17 Star Sports 1 Tamil SD Sports 17.00 18 Star Sports 1 Telugu SD Sports 19.00 19 Star Sports 1 Kannada SD Sports 19.00 20 Star Sports Select 1 SD Sports 19.00 21 Star Sports Select 2 SD Sports 7.00 22 Movies Ok SD Movies (Hindi) 1.00 23 Star Jalsha Movies SD Movies (Bangla) 6.00 Star Maa Gold General Entertainment 24 SD (Telugu) 2.00 General Entertainment 25 Star Suvarna Plus SD (Kannada) 5.00 26 Star Sports 2 SD Sports 6.00 27 Star Sports 3 SD Sports 4.00 28 Fox Life SD Lifestyle 1.00 29 Star Utsav SD General Entertainment (Hindi) 1.00 30 Star Gold Thrills SD Movies (Hindi) 1.00 31 Star Utsav Movies SD Movies (Hindi) 1.00 32 Star Maa Music SD Music (Telugu) 1.00 33 Star Vijay Super SD General Entertainment (Tamil) 2.00 General Entertainment -

Genre Channel List Genre Channel List Star Plus HD Star Plus HD Colors HD Colors HD ZEE TV HD ZEE TV HD SONY HD SONY HD Star

33 HD Channels All HD Channels Genre Channel List Genre Channel List Star Plus HD Star Plus HD Colors HD Colors HD ZEE TV HD ZEE TV HD SONY HD SONY HD Hindi Entertainment Hindi Entertainment Star Bharat HD HD Star Bharat HD HD AND TV HD AND TV HD Jeet HD Jeet HD Sony SAB HD Sony SAB HD Star Gold HD Star Gold HD Zee Cinema HD Zee Cinema HD andpictures HD andpictures HD Hindi Movies Hindi Movies SONY MAX HD SONY MAX HD Star Gold Select HD Star Gold Select HD Ciniplex HD Ciniplex HD Music Sony Rox HD Music Sony Rox HD National Geographic Channel HD National Geographic Channel HD Discovery HD World Discovery HD World History TV 18 HD History TV 18 HD Infotainment & Fox Life HD Infotainment & Fox Life HD Lifestyle Animal Planet World HDLifestyle Animal Planet World HD BBC Earth HD TLC World HD Living Foods HD Living Foods HD TLC World HD BBC Earth HD News Times Now HD News Times Now HD STAR JALSHA HD STAR JALSHA HD JALSHA MOVIES HD JALSHA MOVIES HD Bengali Bengali Colors Bangla HD Colors Bangla HD Zee Bangla HD Zee Bangla HD STAR PRAVAH HD STAR PRAVAH HD Colors Marathi HD Colors Marathi HD Marathi Marathi Zee Marathi HD Zee Marathi HD Zee Talkies HD Zee Talkies HD Star Sports 2 HD D Sports HD Sony Six HD Star Sports 1 HD Star Sports 2 HD Star Sports 1 Hindi HD Sports Sports Sony TEN1 HD Sony TEN2 HD Sony TEN3 HD Sony ESPN HD Star Sports Select 1 HD Star Sports Select 2 HD Star World HD Star World Premiere HD AXN HD English Entertainment COLORS INFINITY HD Disney International HD ZEE CAFE HD COMEDY CENTRAL HD Star Movies HD Zee Studio HD Sony Pix HD HBO HD Star Movies Select HD English Movies MN+ HD Romedy Now HD MOVIES NOW HD Le Plex HD & Prive HD MNX HD ASIANET HD Malayalam Mazhavil Manorama HD Colors Kannada HD Kannada Star Suvarna HD Tamil Star Vijay HD Maa HD Telugu ETV HD Maa Movies HD Kids Nick HD. -

The Role of the Nation-State: Evolution of STAR TV in China and India By

The role of the nation-state: Evolution of STAR TV in China and India By Yu-li Chang Assistant Professor Department of Communication Northern Illinois University E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (815)753-1711 Copyright © 2006 by Yu-li Chang Paper Submitted to the 6th Annual Global Fusion Conference Chicago, 2006 Abstract The purpose of this study is to examine the role of the nation-state by analyzing the evolution of STAR TV’s in India and China. STAR TV, the first pan-Asian satellite television, represents the global force; while the governments in India and China represent the local forces faced with challenges brought about by globalization. This study found that the nation-states in China and India still were forces that had to be dealt with. In China, the state continued to exercise tight control over foreign broadcasters in almost every aspect – be it content or distribution. In India, the global force seemed to have greater leverage in counteracting the state, but only in areas where the state was willing to compromise, such as allowing entertainment channels to be fully owned by foreign broadcasters. In areas where the government thought needed protection to ensure national security and identity, the state still exercised autonomy to formulate and implement policies restricting the global force. Author Bio The author earned her Ph.D. from the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University in 2000 and is now an assistant professor in the department of communication at Northern Illinois University. Her major research interest focuses on globalization of mass media, especially programming strategies of transnational satellite broadcasters in Asia and the implications of their programming strategies on theory building in the research field of globalization. -

D:\Channel Change & Guide\Chann

CHANNEL GUIDE UPDATED AS OF 1ST JULY 2020 FTA = Free To Air SCR = Scrambled Radio Channels in Italics FREQ/POL CHANNEL SR FEC CAS NOTES ARABSAT 5C at 20.0 deg E: Bom Az 256 El 27, Blr Az 262 El 24, Del Az 253 El 20, Chen Az 263 El 21, Bhopal Az 256 El 21, Cal Az 261 El 11 S 3796 LSRTV 1850 3/4 FTA A 3809 RSSBC TV 1600 2/3 FTA T E 3853 L Espace TV 1388 3/5 Mpeg4 FTA L L 3884 R Iqraa Arabic, ERI TV1, Ekhbariya TV, KSA Sports 2, 2M Monde, El Mauritania. Canal Algeria, Al Maghribia 27500 5/6 FTA I T 3934 L ASBU Bouquet: South Sudan TV, Abu Dhabi Europe, Oman TV, KTV 1, Saudi TV, Sharjah TV, Quran TV, Sudan TV, Sunna TV, E Libya Al Watanya; Holy Quran Radio, Emarat FM, Program One, Radio Quran, Qatar Radio, Radio Oman 27500 7/8 FTA & 3964 L Al Masriyah, Al Masriyah USA, Nile Tv International, Nile News, Nile Drama, Nile Life, Nile Sport, ERTU 1 27500 3/4 FTA C A BADR 5 at 26 deg East: Bom Az 253 El 33.02, Blr Az 259.91 El 29.71, Del 248.93 El 25.47, Chennai Az 260.76 El 26.88, Bhopal Az 252 El 27 B L 4087 L Tele Sahel 3330 3/4 FTA Medium Beam E T 4102 L TNT Niger: Télé Sahel, Tal TV, Espérance TV, Liptako TV, Ténéré TV, Dounia TV, Canal 3 Niger, Canal 3 Monde, Saraounia TV, V Bonferey, Tambara TV, Anfani TV, Labari TV, TV Fidelité, Niger 24, Télé Sahel, Tal TV, Voix du Sahel 20000 2/3 FTA MPEG-4 Medium Beam IRIB: IRIB 1, IRIB 2, IRIB 3 (scr), IRIB 4, IRIB 5, IRINN, Amouzesh TV, Quran TV, Doc TV, Namayesh TV, Ofogh TV, Ifilm, Press 11881 H TV, Varzesh, Pooya, Salamat, Nasim, Tamasha HD, IRIB 3 HD (scr), Omid TV, Shoma TV, Tamasha, Alkhatwar TV, Irkala TV, 27500 5/6 FTA MPEG-4 Central Asia beam Sepehr TV HD; Radio Iran, Radio Payam, Radio Jawan, Radio Maaref etc 11900 V IRIB: IRIB 1, IRIB 2, IRIB 3, IRINN, Amouzesh TV, Salamat TV, Sepehr HD; Radio Iran, Radio Payam, Radio Jawan, Radio Maaref etc.