Enamel Pearl Associated with Localized Periodontitis in Hellenistic Age Woman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary for Narrative Writing

Periodontal Assessment and Treatment Planning Gingival description Color: o pink o erythematous o cyanotic o racial pigmentation o metallic pigmentation o uniformity Contour: o recession o clefts o enlarged papillae o cratered papillae o blunted papillae o highly rolled o bulbous o knife-edged o scalloped o stippled Consistency: o firm o edematous o hyperplastic o fibrotic Band of gingiva: o amount o quality o location o treatability Bleeding tendency: o sulcus base, lining o gingival margins Suppuration Sinus tract formation Pocket depths Pseudopockets Frena Pain Other pathology Dental Description Defective restorations: o overhangs o open contacts o poor contours Fractured cusps 1 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 Caries Deposits: o Type . plaque . calculus . stain . matera alba o Location . supragingival . subgingival o Severity . mild . moderate . severe Wear facets Percussion sensitivity Tooth vitality Attrition, erosion, abrasion Occlusal plane level Occlusion findings Furcations Mobility Fremitus Radiographic findings Film dates Crown:root ratio Amount of bone loss o horizontal; vertical o localized; generalized Root length and shape Overhangs Bulbous crowns Fenestrations Dehiscences Tooth resorption Retained root tips Impacted teeth Root proximities Tilted teeth Radiolucencies/opacities Etiologic factors Local: o plaque o calculus o overhangs 2 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 o orthodontic apparatus o open margins o open contacts o improper -

The Role of Alpha V Beta 6 Integrin in Enamel Biomineralization

The Role of Alpha v Beta 6 Integrin in Enamel Biomineralization by Leila Mohazab A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF SCIENCE in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Craniofacial Science) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2013 ⃝c Leila Mohazab 2013 Abstract Tooth enamel has the highest degree of biomineralization of all vertebrate hard tissues. During the secretory stage of enamel formation, ameloblasts deposit an extracellular matrix that is in direct contact with ameloblast plasma membrane. Although it is known that integrins mediate cell-matrix adhesion and regulate cell signaling in most cell types, the receptors that reg- ulate ameloblast adhesion and matrix production are not well characterized. Thus, we hypothesized that αvβ6 integrin is expressed in ameloblasts where it regulates biomineralization of enamel. Human and mouse ameloblasts were found to express both β6 integrin mRNA and protein. The maxil- lary incisors of Itgb6-/- mice lacked yellow pigment and their mandibular incisors appeared chalky and rounded. Molars of Itgb6-/- mice showed signs of reduced mineralization and severe attrition. The mineral-to-protein ra- tio in the incisors was significantly reduced in Itgb6-/- enamel, mimicking hypomineralized amelogenesis imperfecta. Interestingly, amelogenin-rich ex- tracellular matrix abnormally accumulated between the ameloblast layer of Itgb6-/- mouse incisors and the forming enamel surface, and also between ameloblasts. This accumulation was related to increased synthesis of amel- ogenin, rather than to reduced removal of the matrix proteins. This was confirmed in cultured ameloblast-like cells, which did not use αvβ6 integrin as an endocytosis receptor for amelogenins, although it participated in cell adhesion on this matrix indirectly via endogenously produced matrix pro- teins. -

Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Kit Fox (Vulpes Macrotis)

Author's Personal Copy J. Comp. Path. 2019, Vol. 167, 60e72 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/jcpa DISEASE IN WILDLIFE OR EXOTIC SPECIES Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis) N. Yanagisawa*, R. E. Wilson*, P. H. Kass† and F. J. M. Verstraete* *Department of Surgical and Radiological Sciences and † Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, California, USA Summary Skull specimens from 836 kit foxes (Vulpes macrotis) were examined macroscopically according to predefined criteria; 559 specimens were included in this study. The study group consisted of 248 (44.4%) females, 267 (47.8%) males and 44 (7.9%) specimens of unknown sex; 128 (22.9%) skulls were from young adults and 431 (77.1%) were from adults. Of the 23,478 possible teeth, 21,883 teeth (93.2%) were present for examina- tion, 45 (1.9%) were absent congenitally, 405 (1.7%) were acquired losses and 1,145 (4.9%) were missing ar- tefactually. No persistent deciduous teeth were observed. Eight (0.04%) supernumerary teeth were found in seven (1.3%) specimens and 13 (0.06%) teeth from 12 (2.1%) specimens were malformed. Root number vari- ation was present in 20.3% (403/1,984) of the present maxillary and mandibular first premolar teeth. Eleven (2.0%) foxes had lesions consistent with enamel hypoplasia and 77 (13.8%) had fenestrations in the maxillary alveolar bone. Periodontitis and attrition/abrasion affected the majority of foxes (71.6% and 90.5%, respec- tively). -

Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Walrus (Odobenus Rosmarus)

J. Comp. Path. 2016, Vol. -,1e12 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/jcpa DISEASE IN WILDLIFE OR EXOTIC SPECIES Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) J. N. Winer*, B. Arzi†, D. M. Leale†,P.H.Kass‡ and F. J. M. Verstraete† *William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, † Department of Surgical and Radiological Sciences and ‡ Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA, USA Summary Maxillae and/or mandibles from 76 walruses (Odobenus rosmarus) were examined macroscopically according to predefined criteria. The museum specimens were acquired between 1932 and 2014. Forty-five specimens (59.2%) were from male animals, 29 (38.2%) from female animals and two (2.6%) from animals of unknown sex, with 58 adults (76.3%) and 18 young adults (23.7%) included in this study. The number of teeth available for examination was 830 (33.6%); 18.5% of teeth were absent artefactually, 3.3% were deemed to be absent due to acquired tooth loss and 44.5% were absent congenitally. The theoretical complete dental formula was confirmed to be I 3/3, C 1/1, P 4/3, M 2/2, while the most probable dental formula is I 1/0, C 1/1, P 3/3, M 0/0; none of the specimens in this study possessed a full complement of theoretically possible teeth. The majority of teeth were normal in morphology; only five teeth (0.6% of available teeth) were malformed. Only one tooth had an aberrant number of roots and only one supernumerary tooth was encountered. -

Free PDF Download

Eur opean Rev iew for Med ical and Pharmacol ogical Sci ences 2014; 18: 440-444 Radiographic evaluation of the prevalence of enamel pearls in a sample adult dental population H. ÇOLAK, M.M. HAMIDI, R. UZGUR 1, E. ERCAN, M. TURKAL 1 Department of Restorative Dentistry, Kirikkale University School of Dentistry, Kirikkale, Turkey 1Department of Prosthodontics, Kirikkale University School of Dentistry, Kirikkale, Turkey Abstract. – AIM: Enamel pearls are a tooth One theory of the enamel pearl etiology is that anomaly that can act as contributing factors in the enamel pearls develop as a result of a localized development of periodontal disease. Studies that developmental activity of a remnant of Hertwig’s have addressed the prevalence of enamel pearls in epithelial root sheath which has remained adher - populations were scarce. The purpose of this study 5 was to evaluate the prevalence of enamel pearls in ent to the root surface during root development . the permanent dentition of Turkish dental patients It is believed that cells differentiate into function - by means of panoramic radiographs. ing ameloblasts and produce enamel deposits on PATIENTS AND METHODS: Panoramic radi - the root. The conditions needed for local differ - ographs of 6912 patients were examined for the entiation and functioning of ameloblasts in this presence of enamel pearls. All data (age, sex and ectopic position are not fully understood 6,7 . systemic disease or syndrome) were obtained from the patient files and analyzed for enamel The most common site for enamel pearls is at pearls. Descriptive characteristics of sexes, the cementoenamel junction of multirooted jaws, and dental localization were recorded. -

Review Article Autoimmune Diseases and Their Manifestations on Oral Cavity: Diagnosis and Clinical Management

Hindawi Journal of Immunology Research Volume 2018, Article ID 6061825, 6 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6061825 Review Article Autoimmune Diseases and Their Manifestations on Oral Cavity: Diagnosis and Clinical Management Matteo Saccucci , Gabriele Di Carlo , Maurizio Bossù, Francesca Giovarruscio, Alessandro Salucci, and Antonella Polimeni Department of Oral and Maxillo-Facial Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Viale Regina Elena 287a, 00161 Rome, Italy Correspondence should be addressed to Matteo Saccucci; [email protected] Received 30 March 2018; Accepted 15 May 2018; Published 27 May 2018 Academic Editor: Theresa Hautz Copyright © 2018 Matteo Saccucci et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Oral signs are frequently the first manifestation of autoimmune diseases. For this reason, dentists play an important role in the detection of emerging autoimmune pathologies. Indeed, an early diagnosis can play a decisive role in improving the quality of treatment strategies as well as quality of life. This can be obtained thanks to specific knowledge of oral manifestations of autoimmune diseases. This review is aimed at describing oral presentations, diagnosis, and treatment strategies for systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrane pemphigoid, and Behcet disease. 1. Introduction 2. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Increasing evidence is emerging for a steady rise of autoim- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a severe and chronic mune diseases in the last decades [1]. Indeed, the growth in autoimmune inflammatory disease of unknown etiopatho- autoimmune diseases equals the surge in allergic and cancer genesis and various clinical presentations. -

Supernumerary Teeth)

Lecture 7 Paediatric Dentistry Dr. Israa Ali “Dental Anomalies” Dental anomalies are malformations or defects affecting teeth. They usually result from either disturbances to teeth development or they could be as result of environmental influences on teeth. Dental anomalies Developmental Environmental Defects in Effects on teeth number tooth structure Defects in Effects on teeth size tooth color Defects in Effects on teeth shape eruption Defects in teeth structure 11/04/2019 1 Developmental anomalies of dentition: Anomalies Anomalies Anomalies Anomalies of of number of size of shape structure Gemination Ameloenesis Hypodontia Fusion Imperfecta (AI) Microdontia Concrescence Accessory cusps Dentinoenesis Oliodontia Imperfecta (DI) Dens invaginatus Ectopic enamel Anodontia Dentin dysplasia Taurodontism Macrodontia Hypercementosis Accessory roots Regional Hyperdontia Odontodysplasia Dilaceration Developmental anomalies in the number of teeth: 1- Hypodontia: It is agenesis of some teeth (fewer than 6 teeth, not including the third molars). It can occur alone (isolated) or it could be associated with syndromes such as Down’s syndrome. It is uncommon in primary teeth. However, the permanent teeth are more likely to be affected with the most commonly affected teeth to be the third molars followed by mandibular second premolars, maxillary lateral incisors, maxillary second premolars, and mandibular central incisors. 2- Oligodontia: It is a term used to describe the developmental absence of more than six permanent teeth. It is also uncommon in primary teeth; and when the permanent 11/04/2019 2 teeth are affected, collapse of the dental arch and drifting of the few present teeth will result due to presence of excess space. Treatment of both hypodontia and oligodontia involve prosthodontic and orthodontic rehabilitation. -

Unusual Enamel Hypoplasia Associated with Teeth Mobility in a 13 Year Old Girl with Wilson Disease Nehal F

ndrom Sy es tic & e G n e e n G e f Hassib et al., J Genet Syndr Gene Ther 2012, 3:4 T o Journal of Genetic Syndromes h l e a r n a DOI: 10.4172/2157-7412.1000118 r p u y o J & Gene Therapy ISSN: 2157-7412 Case Report Open Access Unusual Enamel Hypoplasia Associated with Teeth Mobility in a 13 Year Old Girl with Wilson Disease Nehal F. Hassib*, Maie A. Mahmoud, Nevin M. Talaat and Tarek H. El-Badry National Research Centre, Giza, Egypt Abstract Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the ATP7B gene. It is characterized by the progressive accumulation of copper in the body leading to liver cirrhosis and neuropsychological deterioration. This case may be the first one reported Wilson disease in association with remarkable enamel hypoplasia and teeth mobility leading to severe teeth destruction and pulp exposure. The objective of this investigation was to introduce the dental management for a 13 year old female patient with Wilson disease. The patients restored her smile and she was highly satisfied of the dental work. In conclusion, the dental management of patients with Wilson disease should become the focus of research because of the difficulty in patients’ management as our patient was suffering from dystonia restricting the mouth opening and in addition of being a mouth breather which affected the time and quality of the dental work. Keywords: Wilson disease; Enamel hypoplasia; Periodontal disease; lips and prominent philtrum (Figure 1a). Intraoral examination showed Copper disorder metabolism high arched palate, anterior open bite and enamel hypoplasia (Figures 1b and c). -

Developmental Disturbances Affecting Teeth

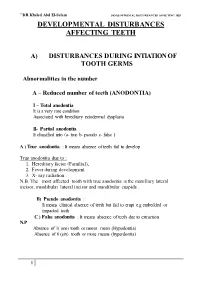

``DR.Khaled Abd El-Salam DEVELO PMENTAL DISTURBANCES AFFECTING TEET DEVELOPMENTAL DISTURBANCES AFFECTING TEETH A) DISTURBANCES DURING INTIATION OF TOOTH GERMS Abnormalities in the number A – Reduced number of teeth (ANODONTIA) I – Total anodontia It is a very rare condition Associated with hereditary ectodermal dysplasia II- Partial anodontia It classified into (a- true b- pseudo c- false ) A ) True anodontia : It means absence of teeth fail to develop True anodontia due to : 1. Hereditary factor (Familial), 2. Fever during development. 3. X- ray radiation . N.B. The most affected tooth with true anodontia is the maxillary lateral incisor, mandibular lateral incisor and mandibular cuspids . B) Pseudo anodontia : It means clinical absence of teeth but fail to erupt e.g embedded or impacted teeth C ) False anodontia : It means absence of teeth due to extraction N.P Absence of 1( one) tooth or mores mean (Hypodontia) Absence of 6 (six) tooth or more means (hyperdontia) 1 ``DR.Khaled Abd El-Salam DEVELO PMENTAL DISTURBANCES AFFECTING TEET ECTODERMAL DYSPLASIA • It is a hereditary disease which involves all structures which are derived from the ectoderm . • It is characterized by (general manifestation) : 1- Skin ( thin, smooth, Dry skin) 2- Hair (Absence or reduction (hypotrichosis). 3- Sweat-gland (Absence anhydrosis). 4- sebaceous gland ( absent lead to dry skin) 5-Temperature elevation (because of anhydrosis) 6- Depressed bridge of the nose 7- Defective mental development 8- Defective of finger nail Oral manifestation include teeth and -

Analysis of the COL17A1 in Non-Herlitz Junctional Epidermolysis Bullosa and Amelogenesis Imperfecta

333-337 29/6/06 12:35 Page 333 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR MEDICINE 18: 333-337, 2006 333 Analysis of the COL17A1 in non-Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa and amelogenesis imperfecta HIROYUKI NAKAMURA1, DAISUKE SAWAMURA1, MAKI GOTO1, HIDEKI NAKAMURA1, MIYUKI KIDA2, TADASHI ARIGA2, YUKIO SAKIYAMA2, KOKI TOMIZAWA3, HIROSHI MITSUI4, KUNIHIKO TAMAKI4 and HIROSHI SHIMIZU1 1Department of Dermatology, 2Research Group of Human Gene Therapy, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine, Sapporo 060-8638; 3Department of Dermatology, Ebetsu City Hospital, Hokkaido; 4Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Received January 31, 2006; Accepted March 27, 2006 Abstract. Non-Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa (nH- truncated polypeptide expression and to a milder clinical JEB) disease manifests with skin blistering, atrophy and tooth disease severity in nH-JEB. Conversely, we failed to detect enamel hypoplasia. The majority of patients with nH-JEB any pathogenic COL17A1 defects in AI patients, in either harbor mutations in COL17A1, the gene encoding type XVII exon or within the intron-exon borders of AI patients. This collagen. Heterozygotes with a single COL17A1 mutation, nH- study furthers the understanding of mutations in COL17A1 JEB defect carriers, may exhibit only enamel hypoplasia. In causing nH-JEB, and clearly demonstrates that the mechanism this study, to further elucidate COL17A1 mutation phenotype/ of enamel hypoplasia differs between nH-JEB and AI genotype correlations, we examined two unrelated families diseases. with nH-JEB. Furthermore, we hypothesized that COL17A1 mutations might underlie or worsen the enamel hypoplasia seen Introduction in amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) patients that are characterized by defects in tooth enamel formation without other systemic Type XVII collagen, 180-kDa bullous pemphigoid antigen is manifestations. -

A Global Compendium of Oral Health

A Global Compendium of Oral Health A Global Compendium of Oral Health: Tooth Eruption and Hard Dental Tissue Anomalies Edited by Morenike Oluwatoyin Folayan A Global Compendium of Oral Health: Tooth Eruption and Hard Dental Tissue Anomalies Edited by Morenike Oluwatoyin Folayan This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Morenike Oluwatoyin Folayan and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3691-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3691-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................. viii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Dental Development: Anthropological Perspectives ................................. 31 Temitope A. Esan and Lynne A. Schepartz Belarus ....................................................................................................... 48 Natallia Shakavets, Alexander Yatzuk, Klavdia Gorbacheva and Nadezhda Chernyavskaya Bangladesh ............................................................................................... -

Focus on Shingles and the Shingles Vaccines - by Allen Lefkovitz

October 2018 THE OMNICARE HealthLine Focus on Shingles and the Shingles Vaccines - by Allen Lefkovitz he current estimates from the Centers for Disease The risk of complications associated with shingles also TControl and Prevention (CDC) are that one in three increases with age. Complications associated with persons in the United States and 50% of adults 85 years shingles include, but are not limited to the following: or older will develop shingles (aka herpes zoster). Shingles Postherpetic neuralgia is a painful, localized skin rash that is caused by the same Scarring virus as chickenpox [i.e., the varicella zoster virus (VZV)]. (PHN) Following chickenpox, VZV remains in the body, but may Bacterial skin infections Vision and/or hearing reactivate many years later resulting in shingles. Shingles (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus) impairment is generally characterized by pain followed by a rash on one side of the body (usually in one or two areas called Pneumonia Social isolation dermatomes). The rash goes on to develop into fluid-filled blisters that typically scab over in 7 to 10 days, and then Brain inflammation Hepatitis gradually resolve in 2 to 4 weeks. Beyond pain and itching, other symptoms of shingles may include fever, headache, Weakness or paralysis Death sensitivity to light, and/or nausea. While exposure to someone with shingles does not PHN is the most common complication of shingles and increase your risk of shingles, individuals who have never may occur in up to 20% of individuals with shingles. PHN had chickenpox and who have never been vaccinated for involves persistent pain in the area where the rash used chickenpox are at risk of contracting VZV.