Colby, William E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multimediali Catalogo Dei DVD

Biblioteca Tiziano Terzani Comune di Campi Bisenzio Villa Montalvo - Via di Limite 15 – 50013 Campi Bisenzio Tel. 055 8959600/2 – fax 055 8959601 www.comune.campi-bisenzio.fi.it/biblioteca [email protected] Multimediali Catalogo dei DVD A cura di Elena Tonini Ottobre 2018 Cataloghi e bibliografie: Catalogo dei DVD Lo spazio multimediale della biblioteca è situato al piano terreno, in prossimità dell’accoglienza e dei punti Internet. Qui sono disponibili sia CD audio che film, cartoni animati, spettacoli teatrali e concerti in DVD. E’ possibile prende re in prestito fino a 3 documenti contemporaneamente per 7 giorni. Il catalogo è suddiviso in 4 sezioni (Documentari, Spettacolo, Film, Animazione) ed è ordinato alfabeticamente per regista o titolo. Nella bibliografia il testo racchiuso tra parentesi quadrate che completa la citazione bibliografica (es.[Z DVD 791.43 ALL]) indica la collocazione del documento in biblioteca. 2 Biblioteca Tiziano Terzani Cataloghi e bibliografie: Catalogo dei DVD Documentari Regione Toscana. Consiglio regionale, 2008, 1 dvd (15 min.) [Z DVD 158.12 TOL] Eckhart Tolle . Portare la quiete nella vita [Z DVD 332.750 973090511 GIB] quotidiana , Cesena, Macrovideo, 2008, 28 p. Alex Gibney . Enron: it's just a business , (Nuova saggezza) Milano, Feltrinelli, c2006, 1 dvd (110 min.) (Real cinema) [Z DVD 252 MAS] Stefano Massini . Io non taccio: prediche di [Z DVD 342.450 23 SCA] Girolamo Savonarola , Bologna, Corvino Meda, Oscar Luigi Scalfaro . Che cos'é la 2011, 105 p. (Promo Music Eyebook) Costituzione? , Roma, L'Espresso, 2009, 1 dvd (ca. 70 min.) [Z DVD 252 MAS] Stefano Massini . -

2006 November Family Room Schedule

NOVEMBER 2006 PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE FAMILY ROOM Time 10/30/06 - Mon 10/31/06 - Tue 11/01/06 - Wed 11/02/06 - Thu 11/03/06 - Fri 11/04/06 - Sat 11/05/06 - Sun Time THE LIVING FOREST FLIPPER 6:00 AM CONT'D (4:50 AM) DARK HORSE KAYLA CONT'D (5:45 AM) RADIO FLYER 6:00 AM TV-PG CONT'D (5:40 AM) CONT'D (5:40 AM) TV-G CONT'D (5:30 AM) FLIPPER UFO A DOLPHIN IN TIME 6:30 AM A QUESTION OF PRIORITIES 6:15 AM 6:30 AM 6:15 AM G 7:00 AM PG MAGIC OF THE GOLDEN BEAR: GOLDY III 7:00 AM TRADING MOM TV-PG TV-PG 6:40 AM TV-PG THE THUNDERBIRDS THE THUNDERBIRDS THE THUNDERBIRDS 7:30 AM 7:05 AM TRAPPED IN THE SKY PIT OR PERIL SUN PROBE 7:30 AM 7:20 AM 7:20 AM 7:25 AM 8:00 AM 8:00 AM TV-G PG TV-PG TV-PG TV-PG FLIPPER FLIPPER AND THE FUGITIVE (1) UFO THE THUNDERBIRDS UFO 8:30 AM 8:30 AM STOLEN SUMMER THE RESPONSIBILITY SEAT CITY OF FIRE COURT MARTIAL 8:30 AM TV-G 8:15 AM 8:15 AM 8:25 AM 8:15 AM FLIPPER FLIPPER AND THE FUGITIVE (2) 9:00 AM 8:55 AM TV-PG TV-Y7-FV 9:00 AM TV-G OLD SETTLERTV-PG HAMMERBOY UFO 9:30 AM THE LIVING FOREST TV-G 9:05 AM THE SQUARE TRIANGLE 9:05 AM 9:30 AM FLIPPER MOST EXPENSIVE SARDINE IN THE WORLD 9:20 AM 9:50 AM 9:20 AM 10:00 AM TV-G TV-G 10:00 AM FLIPPER FLIPPER AND THE SEAL 10:15 AM TV-G LIL ABNER TV-G FLIPPER FLIPPER DOLPHINS DON'T SLEEP THE FIRING LINE (1) 10:30 AM PG 10:30 AM 10:10 AM 10:20 AM 10:30 AM TV-PG DARK HORSE TV-G TV-G FLIPPER FLIPPER THE THUNDERBIRDS AUNT MARTHA THE FIRING LINE (2) 11:00 AM OPERATION CRASH DIVE 10:40 AM 11:00 AM 10:50 AM 11:00 AM 10:45 AM TV-PG-V TV-PG THE THUNDERBIRDS 11:30 AM TV-PG KAYLA SUN PROBE 11:30 -

Nuclear Navy United States Atomic Energy Commission Historical Advisory Committee

Nuclear Navy United States Atomic Energy Commission Historical Advisory Committee Chairman, Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. Harvard University John T. Conway Consolidated Edison Company Lauchlin M. Currie Carmel, California A. Hunter Dupree Brown University Ernest R. May Harvard University Robert P. Multhauf Smithsonian Institution Nuclear Navy 1946-1962 Richard G. Hewlett and Francis Duncan The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London The University of Chicago Press Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press Ltd., London Published 1974 Printed in the United States of America International Standard Book Number: 0-226-33219-5 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 74-5726 RICHARD G. HEWLETT is chief historian of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission. He is coauthor, with Oscar E. Anderson, Jr., of The New World, 1939-1946 and, with Francis Duncan, of Atomic Shield, 1947-1952. FRANCIS DUNCAN is assistant historian of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. He is the coauthor of Atomic Shield. [1974] VA Contents Illustrations vii Foreword ix Preface xi 1 2 3 4 Control The The The of the Idea Question of Structure Sea and the Leadership of Responsi- 1 Challenge 52 bility 15 88 5 6 7 8 Emerging Prototypes Toward Nuclear Patterns of and a Nuclear Power Technical Submarines Fleet Beyond Management 153 194 the Navy 121 225 9 10 11 12 Propulsion Building Fleet The for the the Nuclear Operation Measure Fleet Fleet and of Accom- 258 297 Maintenance plishment 340 377 Appendix 1: Table of Organization Abbreviations 404 393 Notes 405 Appendix 2: Construction of the Sources 453 Nuclear Navy 399 Index 461 Appendix 3: Financial Data 402 V Illustrations Charts 8. -

Cs 001 437 Teacher Uses the Doze Procedure As a Nay to Analyze Poetry," Language-Experience Approach to Reading Instruction

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 098 519 cs 001 437 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE The Teaching of Reading and the English Classroom. INSTITUTION krimona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Nov 74 NOTE 171p. JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v17 n1 Entire Issue Nov 1974 RDRS PRICE MF-S0.75 HC-$7.80 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *English Instruction; *Instructional Materials; Intermediate Grades; Language Arts; Reading Comprehension; *Reading Instruction; *Reading Skills; Secondary Education; *Teaching Methods ABSTRACT This issue of the "Arizona English Bulletin" provides ideas, suggests materials, and discusses techniques thatmay prove useful to English teachers who are also responsible for teaching intermediate, junior, and senior high school students howto read. The contents include "Reading, Language, and Thinking," "A Good English Teacher Is a Teacher of Reading," "How EnglishTeachers Can Prepare Themselves to Teach Reading," "A Class for All Reasons," "A Teacher Uses the doze Procedure as a Nay to Analyze Poetry," "Activities for Non-Readers and Reluctant Readers," "The Language-Experience Approach to Reading Instruction," "Contributions of English to Reading and Reading to English." "Motivating Reading; Using Media in the English Classroom," "Evaluating Some Reading Related Factors in the English Classroom," "What the EnglishTeacher Should Know about Teaching Reading," and "Black Dialect Shift in Oral Reading." (RB) S DEPARTMENT OFNEAL Ttt r-4 EDUCATION A WELFARE NATIONAL tNSttftf,t OP, Ho, EDUCATION L'( Mr NV MA%Nit EN4iE PPC CC) t -

The Illinois Education Review Is Published Urbana- Education Alumni Association of the University of Illinois at Champaign

3TO. 5 rue -V.2/IO.I v. l no.\ ? x *£MG7-£ St o^aG£ rn»l«n.l »» The person charging W. below Latest Date stamped University. ! Jicmi«al from the AUG 15 fEB L16 l__O-l096 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/illinoiseducatio1121univ blume I, Number 1 Summer, 1972 fHE ILLINOIS EDUCATION REVIEW A PUBLICATION OFTHE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN J.MYRON ATKIN, DEAN and COLLEGE OF EDUCATION ALUMNI ASSOCIATION JOSEPH DEATON, PRESIDENT and THE OFFICE FOR PROFESSIONAL SERVICES IN EDUCATION THOMAS L. McGREAL, DIRECTOR periodically by the College of The Illinois Education Review is published Urbana- Education Alumni Association of the University of Illinois at Champaign. Articles for consideration should be sent to: The Illinois Education Review 140 Education Building University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 61801 encouraged Demurrals, rebuttals, comments, and letters to the editors are and contributory. See and will be considered for publication if undersigned detailed statement of editorial policy. The Volume I, Number 1 for a more paid-up membership in the Illinois Education Review is available free with non-members — 3 - 00 - Education Alumni Association. Single copy price for j Association and send to editorial (Make checks payable to U. of I. Alumni office, address above.) Thomas L. McGreal, Editor Gates, Associate Editor J . Terry E. Sue Buchanan, Editorial Assistant 9s S 5 KEMOTE STORAOS TABLE OF CONTENTS A FIRST EDITION Hi THE SCHOOL ADMINISTRATOR AND THE PURPOSE OF EDUCATION Dr. George P. Young 7 > CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION: NEED, SCOPE, AND SETTING Alan B. -

Religious Fundamentalisms on the Rise: a Case for Action Women’S Rights Awid

Religious Fundamentalisms on the Rise: A case for action women’s rights awid www.awid.org Acknowledgements This publication is one in a series of products based on a research endeavour by AWID that began in early 2007 and brought together a team of brilliant minds. In particular, we would like to thank Cassandra Balchin, who contributed her sharp analysis, quick wit and knowledge of Muslim fundamentalisms as the lead research consultant for the project, as well as Juan Marco Vaggione, who joined us as the second research consultant a few months later and to whose humour, generosity and perspective on religious fundamentalisms in Latin American we are all indebted. I would also like to thank the entire AWID team that worked on the initiative, and all the staff who were on separate occasions pulled into assisting with it. In particular, I would like to acknowledge the research and writing expertise of Deepa Shankaran, the coordination and editing skills of Saira Zuberi, and the contributions of Ghadeer Malek and Sanushka Mudaliar from the Young Feminist Activism initiative. A special thank you to Lydia Alpízar, AWID’s Executive Director, and Cindy Clark for their leadership, guidance and support through this project. The survey results that are presented here would not have been possible without the generous contribution of Martin Redfern, who lent us his technical expertise in the area of survey design, data collection and statistics. I would also like to thank Jessica Horn for adding to feminist analyses of Charismatic and Pentecostal churches in the Sub- Saharan African region. A special mention goes to the funders whose generous support made this work possible - in particular, the Sigrid Rausing Trust, the Open Society Institute, and Hivos, as well as the organizations that provide AWID’s core funding, listed at the back of this publication. -

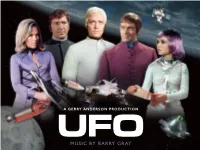

Gerry Anderson's PREMISE: in the Late 1960S, the United States

Gerry Anderson’s UFO PREMISE: In the late 1960s, the United States government issued a report officially denying the existence of Unidentified Flying Objects. The government agencydesigned to look into the phenomenon, Project Blue Book, was also closed down and people were led to believe that (as far as the government was concerned) UFOs had not come to Earth. The format of the television series takes this occurrence as a cover-up by the government in an attempt to hide the fact that we were not only visited by creatures from space, but brutally attacked. Their reasoning was that mass hysteria and panic would result if the common man discovered that his world was being invaded by extraterrestrials. So, in secret, the major governments of the world created SHADO − Supreme Headquarters, Alien Defense Organi- zation. From it’scenter of operations hidden beneath a film studio (where bizarre comings and goings would remain commonplace), SHADO commands a fleet of submarines (armed with sea-to-air strikecraft), aircraft, land vehicles, satellites and a base on the Moon. MAJOR CHARACTERS: COMMANDER ED STRAKER−Leader of SHADO. He is totally dedicated to his job, almost to the point of obsession. COLONEL ALEC FREEMAN−Straker’ssecond-in-command. COLONEL PAULFOSTER−Former test pilot recruited to SHADO. CAPTAIN PETER CARLIN−Commander and interceptor pilot of Skydiver1. MISS EALAND−Straker’ssecretary for his film studio president cover. LT . MARK BRADLY−Moonbase interceptor pilot. LT . LEW WATERMAN−Moonbase interceptor pilot, later promoted to SkydiverCaptain. LT . JOAN HARRINGTON−Moonbase Operative. LT . FORD−SHADO Control Radio Operator LT . GAYELLIS−Moonbase Commander COLONEL VIRGINIA LAKE−Designer of the Utronic tracking equipment needed to detect UFOs in flight. -

MUSIC by BARRY GRAY the Earth Is Faced with a Power Threat from an Dateline:1980 EXTRATERRESTRIAL Source

A GERRY ANDERSON PRODUCTION UFO MUSIC BY BARRY GRAY The Earth is faced with a power threat from an Dateline:1980 EXTRATERRESTRIAL source... we have moved After a decade of creating pioneering puppet series made for children, the Andersons took their first into an age where SCIENCE FICTION has become steps into live-action, with the 1969 feature film FACT. We need to DEFEND ourselves. Doppelgänger (re-titled outside Britain as Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun). This science-fiction film COMMANDER ED STRAKER approached its outer space subject matter with a gritty realism, and would set the tone for what was to be their first live-action television series:UFO . This new series took as a starting point the pioneering work of Dr Christiaan N. Barnard, the surgeon who performed the world’s first heart transplant operation. In UFO a dying race of aliens travel across vast distances of space to harvest organs from human beings to help ensure their own survival. To combat this threat the United Nations created SHADO, a top-secret organisation utilising the latest technology available to defend the Earth. To complement the series, the Andersons frequent musical collaborator Barry Gray created a multifaceted score that gave the programme its own musical identity. This Album is the very first commercial release of Gray’s score, making it finally available to more listeners worldwide. Welcome to SHADO SHADO – Supreme Headquarters Alien Defence Organisation – is based from a secret headquarters deep beneath the Harlington Straker Film Studio. Earth’s first line of defence is SID, the Space Intruder Detector, a satellite in Earth’s orbit created to spot incoming UFOs. -

A New Approach to Research Ethics

A New Approach to Research Ethics A New Approach to Research Ethics is a clear, practical and useful guide to the ethical issues faced by researchers today. Examining the theories of ethical decision-making and applying these theories to a range of situations within a research career and process, this text offers a broader perspective on how ethics can be a positive force in strengthening the research community. Drawing upon a strong selection of challenging case studies, this text offers a new approach to engage with ethical issues and provides the reader with: • a broader view on research ethics in practice, capturing both different stages of research careers and multiple tasks within that career, including supervision and research assessments; • thoughts on questions such as increasing globalisation, open science and intensified competition; • an increased understanding of undertaking research in a world of new technologies; • an extension of research ethics to a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approach; and • an introduction to a ‘guided dialogue’ method, which helps to identify and engage with ethical issues individually and as a research community. A New Approach to Research Ethics allows for self-reflection and provides guidance for professional development in an increasingly competitive area. Full of valuable guidance for the researcher and ethical decision-maker, this is an essential text for postgraduate students, senior academics and developers of training courses on ethics for researchers. Henriikka Mustajoki has a career in professional ethics focusing on research ethics. Arto Mustajoki has a long career as a professor and scientific administrator. He has been department head, dean and vice-rector of the University of Helsinki. -

Being Sick Well ___

Introduction The Trend and How to Cope My wife, Pat, had two heart attacks and two strokes. She had diabetes, her kidneys failed, and she went on dialysis. She had bypass surgery on her legs, but eventually both were amputated above the knees. Over several decades she went blind and her hands became numb. At age fifty she died. What kept Pat upbeat despite all this? Three things. First, she was a devoted mother. She was willing to go through anything, provided that our daughter, Felicity, was okay. Second, Pat and I became increasingly spiritual. Medical research shows that spirituality is a powerful resource for dealing with stress. We were devoted servants of Jesus Christ. We prayed often for healing, but God’s answer was, “Not yet!” Third, Pat’s medical disasters were not her main experience in life. The diseases were often quiet and well behaved. There were long periods of normal life. Even when Pat was on peritoneal dialysis, it became part of the ordinary routine. Life itself was delicious. It was sometimes possible to deny the danger, ignore the illnesses, and simply enjoy the blessings that God sent us in such abundance.1 I cannot say that Pat and I were always successful in dealing with her illness. In the end I was humbled, feeling I had not been as good a caregiver as I should have been. Page 7 Page 8 There is an epidemic of chronic illness today. Catherine Hoffman found that 90 million Americans had a chronic illness in 1987.2 By 1998 that number grew to 120 million, according to Gerard Anderson’s research team at Johns Hopkins.3 At least 45 percent of all Americans have a chronic condition, accounting for 78 percent of the healthcare budget.4 These numbers are increasing. -

Health & Human Development in the New Global Economy

Galveston.qxd 4/19/00 12:29 PM Page i Health & Human Development in the New Global Economy: The Contributions and Perspectives of Civil Society in the Americas Editors Division of Health and Human Development Pan American Health Organization Regional Office of the Americas Alexandra Bambas World Health Organization Juan Antonio Casas Harold A. Drayton University of Texas Medical Branch América Valdés Washington, D.C., U.S.A., © 2000 Galveston.qxd 4/19/00 12:29 PM Page ii Reference Bambas, Alexandra; Casas, Juan Antonio; Drayton, Harold A.; and Valdés, America. (Eds.) (2000). Health and Human Development in the New Global Economy: The Contributions and Perspectives of Civil Society in the Americas. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). This publication derives from presentations and discussions at the Seminar/Workshop co- sponsored by the University of Texas Medical Branch, the Pan American Health Organization, and the World Health Organization, which was held in Galveston, Texas, USA, October 26-28, 1998. Materials in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested together with a reference to the title and the ISBN number. A copy of the publication containing a quote or reprint should be sent to the Division of Health and Human Development of the Pan American Health Organization/WHO, 525 Twenty-Third Street NW,Washington,DC 20037, and another to the UTMB/WHO Collaborating Center for International Health, 301 University Blvd., Galveston, Texas 77555. Copyright 2000 by the Pan American Health Organization, unless otherwise noted. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: ISBN In order to disseminate this information broadly, at the time of publication, this document is available in full text on the World Wide Web in English at www.paho.org/english/hdp/hdp.htm and in Spanish at www.paho.org/spanish/hdp/hdp.htm. -

00 Front Last.Indd

MONOGRAPHS IN GERMAN HISTORY VOLUME 26 MONOGRAPHS IN GERMAN HISTORY After the ‘Socialist spring’ After After the ‘Socialist Spring’ VOLUME 26 COLLECTIVISATION AND ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION IN THE GDR George Last Historical analysis of the German Democratic Republic has tended to adopt a top-down model of the transmission of authority. However, developments were more complicated than the standard state/society dichotomy that has dominat- ed the debate among GDR historians. Drawing on a broad range of archival material from state and SED party sources as well as Stasi files and individual farm records along with some oral history interviews, this book provides a thorough investigation of the transformation of the rural sector from a range of perspectives. Focusing on the region of Bezirk Erfurt, the author examines on the one hand how East Germans responded to the end of private farming by resisting, manipulating but also participating in the new system of rural organization. However, he also shows how the regime sought via its representatives to imple- ment its aims with a combination of compromise and material incentive as well as administrative pressure and other more draconian measures. The reader thus gains valuable insight into the processes by which the SED regime attained stability in the 1970s and yet was increasingly vulnerable to growing popular dissatisfaction and economic stagnation and decline in the 1980s, leading to its eventual collapse. George Last holds a BA from Oxford University and took his MA and Ph.D. George Last at University College London, where he has also taught. He now works on value-for-money research for the National Audit Office.