Banff and Macduff Overview 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornhill and Ordiquhill Community Action Plan

Cruden Bay Community Action Plan May 2018 1 Location Community Action Plan 2 Introduction Community Action Plan This is the Community Action Plan for the This plan will only be delivered if all parties, communities of Cornhill, Ordiquhill and the community and public agency, cooperate surrounding rural area. It has been developed and communicate. It certainly cannot be by Banffshire Partnership Ltd following a delivered by one group acting on their own. community engagement event held at Ordiquhill School on 15th May 2018. All the The table at the back shows those ideas split ideas in this booklet came from the community. into those that can be taken forward by the community on its own, those which require The event was attended by individual local help from an external partner, and those residents and representatives of local community which can only be taken forward by one or groups. Local councillors and officials from more external agencies. We hope such agencies Aberdeenshire Council were also present as will also provide encouragement, plus observers and helpers, but they did not steer technical and possibly financial support too or add their views to the information where needed. gathering. During the evening the residents and It is recommended that this Action Plan has a community group representatives put forward maximum lifespan of 3 years. Some projects many ideas in 6 specific categories and the may be completed quickly whist others may majority of these ideas have been distilled take much longer, but all should be reviewed into those listed in the table at the end of this regularly to ensure that they are still relevant. -

IAPC 110918 Minutes

AGENDA ITEM DISCUSSION ACTIONS RESPONSIBLE Welcome Meeting followed AGM. Elizabeth welcomed our guests, Dawn Lynch (DHT), Shona Lees (MCR Pathways) and Brodie (School Captain). Attending/ Attending: Elizabeth Watt, Emma West, Shona Strachan, Stuart Laird, Samantha Apologies Tribe, Lyndsay Aspey, Tracey Skene, Kay Diack, Cllr Lesley Berry, Sam Grant, Valerie Napier, Cllr Marian Ewenson, Cllr Judy Whyte, Anne Hitchcox, Shaz Cowling, Sheila Cunningham, Vicky Mackintosh, Michelle Charles, Lyne Western, Gail Hempseed, Juliet Serrell, Deborah Collinson, Claire Green, Lindsay MacInnes, Emma Stephenson, Mark Jones (HT), Shona Lees (MCR Pathways), Dawn Lynch (DHT), Brodie (School Captain). Apologies: Louise Liddell, Cllr Neil Baillie, Guy Carnegie, Sue Redshaw Approval of Proposed: Sam Grant previous Seconded: Valerie Napier Minutes MCR Pathways Shona Lees and Dawn Lynch presented this topic. The MCR Pathways approach began in Glasgow City around 10 years ago. The programme works to raise the aspirations of the young people involved and so increase their chance of achieving and sustaining a successful destination following school. Inverurie Academy was offered the opportunity to become involved with an Aberdeenshire pilot in 2016 and worked with a small number of young people, (around 12), and Befriend a Child in order to trial this. Most of the young people who engaged with the programme had notable improvements in the areas they had identified as priority. 1 AGENDA ITEM DISCUSSION ACTIONS RESPONSIBLE We carefully considered how to prioritise the use of our Pupil Equity Fund allocation and believe that this project is right for our school and community. Shona Lees has been seconded into the post of Pathways Coordinator for our school. -

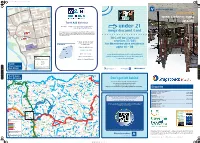

Don't Get Left Behind Turriff Public Transport Guide August 2017

Turriff side 1 Aug 2017.pdf 1 20/07/2017 13:13 ST M 2017 August CHURCH A R E K AC RD E D RR NFIEL E T R T CO NE TO S S Guide Transport Public D T GLA 24 B90 47 A9 T TREE P S Turriff FIFE STREET DUFF P Turriff A2B dial-a-bus M A ST I MANSE N S ET Mondays - Fridays: First pick up from 0930 hours T STRE R L P HAPE Last drop off by 1430 hours E C C A E S T T L E H A2B is a door-to-door dial-a-bus service operating in Turriff and outlying I L areas. The service is open to people who have difficulty walking, those L with other disabilities and residents who do not live near or have access PO B to a regular bus route. HIGH REET STR E S T EET ELLI A BALM All trips require to be pre-booked. OAD ON R CLIFT Simply call our booking line to request a trip. Turriff Academy Contact the A2B office on: Q ACE U RR IA T E EE R VICTO N ’ 01467 535 333 S P R O A D Option 1 for Bookings www.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/roads-and-travel/ Option 2 for Cancellations public-transport/under-21-mega-discount-card/ Key or call us 01467 533080 Route served by bus Option 3 for General Enquiries Bus Stop P Car Parking Turriff PO Post Office C Town Centre Created using Ordnance Survey OpenData A M 9 ©Crown Copyright 2016 Bus Stops 4 7 Y CM MY CY Pittulie Sandhaven Fraserburgh CMY Turriff Area Rosehearty K Bus Network Peathill 253 Don’t get left behind Pennan Whitehills Percyhorner Macduff Crovie Banff Gardenstown To receive advanced notification of changes to Auds Coburty bus services in Aberdeenshire by email, Boyndie 35/35A Greenskares Towie Mid Ardlaw A98 Silverford A90(T) sign up for our free alert service at Dubford New Gowanhill Longmanhill Aberdour https://online.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/Apps/publictransportstatus/ 35/35A Dounepark Cushnie Boyndlie Tyrie Memsie Enquiries To Elgin Mid Culbeuchly A97 Whitewell A98 Ladysford A98 Rathen Union Square Bus Station All Enquiries Kirktown Minnonie of Alvah 0800-1845 (Monday to Friday)............................................................................ -

THE PINNING STONES Culture and Community in Aberdeenshire

THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire When traditional rubble stone masonry walls were originally constructed it was common practice to use a variety of small stones, called pinnings, to make the larger stones secure in the wall. This gave rubble walls distinctively varied appearances across the country depend- ing upon what local practices and materials were used. Historic Scotland, Repointing Rubble First published in 2014 by Aberdeenshire Council Woodhill House, Westburn Road, Aberdeen AB16 5GB Text ©2014 François Matarasso Images ©2014 Anne Murray and Ray Smith The moral rights of the creators have been asserted. ISBN 978-0-9929334-0-1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 UK: England & Wales. You are free to copy, distribute, or display the digital version on condition that: you attribute the work to the author; the work is not used for commercial purposes; and you do not alter, transform, or add to it. Designed by Niamh Mooney, Aberdeenshire Council Printed by McKenzie Print THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire An essay by François Matarasso With additional research by Fiona Jack woodblock prints by Anne Murray and photographs by Ray Smith Commissioned by Aberdeenshire Council With support from Creative Scotland 2014 Foreword 10 PART ONE 1 Hidden in plain view 15 2 Place and People 25 3 A cultural mosaic 49 A physical heritage 52 A living heritage 62 A renewed culture 72 A distinctive voice in contemporary culture 89 4 Culture and -

Bag Net Fishing Returns to Gardenstown

16 SALMON FISHING www.intrash.com/sheries 17 August 2012 After a twenty year gap, the resumption of traditional fixed Bag net engine salmon netting on the souther shore fishing of the Moray Firth from Gardenstown returns to harbour is highly encouraging – not least Gardenstown because it comes at a time when numbers of fishermen on Scotland’s east coast is at an all- time low Report and photos by David Linkie he purchase by the family run Usan Salmon Fish- Teries Ltd of the rights to operate bag stations from Rosehearty west to More Head has been welcomed by resi- dents of Gardenstown, home to one of the largest owner- ship concentrations of shing vessels, including midwater and prawn twin rig trawlers in Scotland. Although the days of herring drifters landing nightly catches at Gardenstown are distant memories, the tidal harbour nestled under towering cliffs continues to be used by a size- able eet of seasonal static gear boats shing for lobsters Gamrie, which will be devel- stand comparison with their vourable conditions have been for their rst season Usan and mackerel in the summer. oped next winter to provide other locations in Scotland. compounded further by much Salmon Fisheries took the The arrival earlier this year living accommodation during Unfortunately, since starting rain which in turn has led to decision to operate in prox- of the traditional salmon coble the ve-month season to the 2012 netting season on coloured ood water entering imity to Gardenstown harbour, Usan Lass has helped increase replace the temporary caravan. the east coast of Scotland the sea. -

Aberchirder (Aberkerder), Archibald De Altyre : See Blairs, Loch Of

INDEX Aberchirder (Aberkerder), Archibald de Altyre : see Blairs, Loch of. (1343), . 89/., 90 Amphoree : — —— —— Sybil de, ...... 90 at Linlithgow, ... 353 —— —— Symon, Than , e...of . 00 Brochfrow mBo , Midlothian. , 289, 351 —— —— Thane , .....sof 0 9 . „ Constantine's Cave, Fife. , . 288, 383 —— (Aberkerdour), Joh o, f n . Essyde 89/ .. , e Ghegath „ n Rock, Seacliff, E. Aberdeen ofp SteatitCu , e. from.10 . , 2 Lothian, ..... 288,354 —— Horn Snuff-mull from, ...3 10 . ,, "West Grange of Conan, Angus, . 287 Aberdeenshire, Axe-hammer from, . 102 Small Model, from Baldock, . .109 See also Aberchirder; Auchindoir; Auch- Anchor (?), Stone, from Yarlshof, . 121, 127 lin, Aberdour ; Auldyooh ; Balhinny ; Ancrum, Roxburghshire, Coin of Geta from, 350 Birse; Brackenbraes, Turriff; Cairn- Anderson , presenteG. , . RevS . dR . Com- hill, Monquhitter; Craig Castl eDess; , munion Tokens, ..... 17 Aboyne ; Bruminnor; Essie ; Fing- Andrew, Saint, Translation of, Feast of, . 427 lenny; Glencoe; Knockwhern, Echt; Angus : see Airlie ; Auchterhouse ; Conan, Lesmoir Castle ; Maiden Hillock ; West Grange of; Fithie ; Kingol- Milduan; Scurdargue; Tarve sTemp; - drum ; Knockenny, Glamis ; Mon- land, Essi e; Towi e Barclay Castle; tros e; Pitcu r ; Tealing, Dundee. Turriff; WaulkmUl, Tarland. Ani Imanni [o], Potter, Stamp of, . 355 Adiectus, Potter, Stamp of, . 284, 288, 352 Animal Life in Caledonia, .... 348 Adrian, Saint, ...... 427 —— Remains from Barn's Heugh, near Adze, Stone :— Coldingham, .... .18 . .2 from Break of Mews, Shetland, . 76 —— — — from Rudh Dunainn a ' 0 20 , Skye . , „ Setter, Shetland, ...6 7 . Annandale, Handle of Bronze Skillet from, ,, Taipwell, Shetland,,. 76 301, 3439 ,36 Africa, East, Knives and Scrapers of Anniversary Meeting, 1931, .... 1 Obsidian from Gilgil8 1 ,. Kenya . , Anstruther-Gray, Colone , electeW. l o t d —— West, Stone Implements, etc., from Council, ...... -

(03) ISC Draft Minute Final.Pdf

Item: 3 Page: 6 ABERDEENSHIRE COUNCIL INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES COMMITTEE WOODHILL HOUSE, ABERDEEN, 3 OCTOBER, 2019 Present: Councillors P Argyle (Chair), J Cox (Vice Chair), W Agnew, G Carr, J Gifford (substituting for I Taylor), J Ingram, P Johnston, J Latham, I Mollison, C Pike, G Reid, S Smith, B Topping (substituting for D Aitchison) and R Withey. Apologies: Councillors D Aitchison and I Taylor. Officers: Director of Infrastructure Services, Head of Service (Transportation), Head of Service (Economic Development and Protective Services), Team Manager (Planning and Environment, Chris Ormiston), Team Leader (Planning and Environment, Piers Blaxter), Senior Policy Planner (Ailsa Anderson), Internal Waste Reduction Officer (Economic Development), Corporate Finance Manager (S Donald), Principal Solicitor, Legal and Governance (R O’Hare), Principal Committee Services Officer and Committee Officer (F Brown). OPENING REMARKS BY THE CHAIR The Chair opened the meeting by saying a few words about the weather and recent flooding across the north of Aberdeenshire, which had seen seven bridges closed, with some being destroyed and others extensively damaged. There was also damage to properties, with gardens and driveways being washed away and the Scottish Fire and Rescue being called out to assist with the pumping of water out from homes. Banff, Macduff, Whitehills, St Combs and Crovie were particularly badly hit, along with the King Edward area. The Chair commended the resilience of the local community, with neighbours looking out for one another and businesses starting the clean-up with repairs underway. The closure of seven bridges around King Edward had been particularly challenging and demonstrated the vulnerability of ageing infrastructure which was simply no longer fit for conditions, whether that was the volume and weight of traffic or extreme weather conditions. -

Made by the Sea

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION presents Made by the Sea 25 June - 13 September 2017 Live archive cinema tour visits coastal communities from Ullapool to the Isle of Barra presenting little-seen gems of Scottish life on our coast and seas Each screening will feature a unique post-film blether with local historians and special guests, encouraging the audience to share their own memories Scotland's coastal communities will take a starring role in the latest outing of A Kind of Seeing’s hugely popular touring programme: Made by the Sea. The tour is supported as part of the BFI’s ‘Britain on Film’ UK-wide project through Film Hub Scotland and the BFI Film Audience Network using funds from the National Lottery. From high drama on the fishing boats to popular seaside destinations, the sea has an important part to play in Scotland's national moving image collection. Featuring archive films from as early as 1908 on the big screen, the Made by the Sea tour opens with a live screening event at Portsoy Salmon Bothy as part of the Scottish Traditional Boat Festival on Sunday 25th June before travelling to five seaside venues across Scotland during the Summer: Ullapool, Tobermory, Johnshaven (as part of the Johnshaven Fish Festival), Thurso, and Castlebay on the Isle of Barra. Each screening on the tour is a chance to experience unusual films local to each location alongside rarely-seen gems from the National Library of Scotland Moving Image Archive and the archives of STV and the RNLI. Highlights will include a wonderful record of village life in 1950s Portsoy, Cullen and Aberchirder filmed by local cinema manager William Davidson; the impact of the Eastern European ‘Klondyker’ factory ships in 1980s Ullapool; a vintage tourist's guide to beautiful Tobermory; King George VI’s Coronation celebrations in Laurencekirk; footage of the 1953 Thurso Gala Week with live musical accompaniment; and a 1920s song-hunter on the Isle of Barra. -

The Fishing-Boat Harbours of Fraserburgh, Sandhaven, Arid Portsoy, on the North-East Coaxt of Scotland.” by JOHNWILLET, M

Prooeedings.1 WILLET ON FRASERBURGH HARBOUR. 123 (Paper No. 2197.) ‘I The Fishing-Boat Harbours of Fraserburgh, Sandhaven, arid Portsoy, on the North-East Coaxt of Scotland.” By JOHNWILLET, M. Inst. C.E. ALONGthe whole line of coast lying between the Firth of Forth and Cromarty Firth, at least 160 miles in length, little natural protection exists for fishing-boats. The remarkable development, however, of the herring-fishery, during the last thirty years, has induced Harbour Boards and owners of private harbours, at several places along the Aberdeenshire and Banffshire coasts, to improve theshelter and increase the accommodation of their harbours, in the design and execution of which works the Author has been engaged for the last twelve years. FIXASERBURGHHARBOUR. Fraserburgh may be regarded as t,he chief Scottish port of the herring-fishery. In 1854, the boats hailing from Fraserburgh during the fishing season were three hundred and eighty-nine, and in 1885 seven hundred and forty-two, valued with their nets and lines atS’255,OOO ; meanwhile the revenue of the harbour increased from 51,743 in 1854 to 59,281 in 1884. The town and harbour are situated on the west side of Fraserburgh Bay, which faces north- north-east, and is about 2 miles longand 1 mile broad. The harbour is sheltered by land, except between north-west and east- south-east. The winds from north round to east bring the heaviest seas into the harbour. The flood-tide sets from Kinnaird Head, at the western extremity of the bay, to Cairnbulg Point at the east, with a velocity of 24 knots an hour ; and the ebb-tide runs in a north-easterly direction from the end of thebreakwater. -

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST Old Age Psychiatry (sub-specialty: Liaison Psychiatry) VACANCY Consultant in Old Age Psychiatry (sub-specialty: Liaison Psychiatry) Royal Cornhill Hospital, Aberdeen 40 hours per week £80,653 (GBP) to £107,170 (GBP) per annum Tenure: Permanent This post is based at Royal Cornhill Hospital, Aberdeen and applications will be welcomed from people wishing to work full-time or part-time and from established Consultants who are considering a new work commitment. The Old Age Liaison Psychiatry Team provides clinical and educational support to both Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and Woodend Hospital and is seen nationally as an exemplar in service delivery. The team benefits from close working relationships with the 7 General Practices aligned Older Adult Community Mental Health Teams in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire and senior colleagues in the Department of Geriatric Medicine. The appointees are likely to be involved in undergraduate and post graduate teaching and will be registered with the continuing professional development programme of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. They will also contribute to audit, appraisal, governance and participate in annual job planning. There are excellent opportunities for research. Applicants must have full GMC registration, a licence to practise and be eligible for inclusion in the GMC Specialist Register. Those trained in the UK should have evidence of higher specialist training leading to a CCT in Old Age Psychiatry or eligibility for specialist registration (CESR) or be within -

Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies

1 From mountain to sea Aberdeenshirep Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies December 2017 2 | Contents 1 BENEFITS 3 2 CHILDCARE AND RESPITE 23 3 COMMUNITY ACTION 43 4 COMPLAINTS 50 5 EDUCATION AND LEARNING 63 6 Careers 81 7 FINANCIAL HELP 83 8 GENERAL SUPPORT 103 9 HEALTH 180 10 HOLIDAYS 194 11 HOUSING 202 12 LEGAL ASSISTANCE AND ADVICE 218 13 NATIONAL AND LOCAL SUPPORT GROUPS (SPECIFIC CONDITIONS) 223 14 SOCIAL AND LEISURE OPPORTUNITIES 405 15 SOCIAL WORK 453 16 TRANSPORT 458 SEARCH INSTRUCTIONS 1. Right click on the document and select the word ‘Find’ (using a left click) 2. A dialogue box will appear at the top right hand side of the page 3. Enter the search word to the dialogue box and press the return key 4. The first reference will be highlighted for you to select 5. If the first reference is not required, return to the dialogue box and click below it on ‘Next’ to move through the document, or ‘previous’ to return 1 BENEFITS 1.1 Advice for Scotland (Citizens Advice Bureau) Information on benefits and tax credits for different groups of people including: Unemployed, sick or disabled people; help with council tax and housing costs; national insurance; payment of benefits; problems with benefits. http://www.adviceguide.org.uk 1.2 Attendance Allowance Eligibility You can get Attendance Allowance if you’re 65 or over and the following apply: you have a physical disability (including sensory disability, e.g. blindness), a mental disability (including learning difficulties), or both your disability is severe enough for you to need help caring for yourself or someone to supervise you, for your own or someone else’s safety Use the benefits adviser online to check your eligibility. -

Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 Km Cairnbulg-Whitelinks Bay-St Combs

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Cairnbulg-Whitelinks Bay-St Combs Circuit (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary This is a bracing walk along the windy coastline at the NE corner of Scotland passing through evocative old fishing villages and crossing the wonderful crescent-shaped beach at Whitelinks Bay. Duration: 2.75 hours. Route Overview Duration: 2.75 hours. Transport/Parking: Stagecoach 69 bus service from Fraserburgh. Check timetable. Free parking at walk start/finish, Cairnbulg Harbour. Length: 8.170 km / 5.11 mi Height Gain: 60 meter. Height Loss: 60 meter. Max Height: 16 meter. Min Height: 0 meter. Surface: Moderate. Mostly on paved surfaces. Some walking on good grassy tracks and a section of beach walking. Difficulty: Easy. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance. Dog Friendly: Yes, but keep dogs on lead on public roads. Refreshments: Options in Fraserburgh. Description This is an enjoyable circuit along the airy coast between Cairnbulg and St Combs, on the “Knuckle of North East Scotland”, where the coastline turns west from the more exposed North Sea to the increasingly more sheltered Moray Firth. The combined villages of Cairnbulg and Inverallochy (the local Community Council is now called “Invercairn”) have a long association with the fishing industry, although as the nature of fishing operations changed, the locus moved to nearby Fraserburgh. The inadequate nature of the original fisher huts was cruelly exposed in the cholera epidemics of the 1860s and they were cleared to make way for planned settlements centred on Inverallochy and Cairnbulg and, a little further down the coast, at St Combs.