Branding Boutique Hotels: Management and Employees’ Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

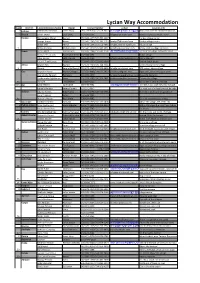

Lycian Way Accommodation

Lycian Way Accommodation Stage Location Accommodation Name Owner Contact Number e-mail Location Info 0 Fethiye Yıldırım Guest House Ömer Yapış 543-779-4732/252-614-4627 [email protected] road close to east boat harbour 1 Ovacik Sultan Motel Unal Onay 252-616-6261 [email protected] Between Ovacik and Olu Deniz Faralya Montenegro Motel Bayram 252-642-1177/536-390-1297 Faralya village center George House Hasan 252-642-1102/535-793-2112 [email protected] Faralya village center Water Mill Ferruh 252-642-1245/252-612-4650 [email protected] Above village 1 Melisa Pension Mehmet Kole 252-642-1012/535-881-9051 [email protected] Below road at village entrance Kabak Armes Hotel Semra Laçin 532-473-1164/252-642-1100 [email protected] of the village below the road Mama's Restaurant Nezmiye Semerci 252-642-1071 Kabak village Olive Garden Fatih Canözü 252-642-1083 [email protected] Below Mama's 2 Turan's Tree Houses Turan 252-642-1227/252-642-1018 Behind Kabak beach Alinca Bayram Bey Bayram 252-679-1169/535-788-1548 Second house in the village 3 Alamut Şerafettin/Şengül 252-679-1069/537-596-6696 info@alamutalınca.com 500 meters above village Gey Bayram's House Bayram/Nurgul 535-473-4806/539-826-7922 [email protected] Right side, 300 meters past pond Dumanoğlu Pension Ramazan 539-923-1670 [email protected] Opposite Bayram's Yediburunlar Lighthouse Sema 252-679-1001/536-523-5881 [email protected] Outside the village 4b GE-Bufe Tahir/Hatice 539-859-0959 On corner in centre of village 4a/b -

List of Hotels, Pension Houses & Inns W

LIST OF HOTELS, PENSION HOUSES & INNS W/ ROOMRATES Bacolod City NAME OF HOTEL ADDRESS TELEPHONE ROOM TYPE RATE 034-433-37- L'Fisher Hotel Main 14th Lacson St. Bacold City 30 Deluxe (single or double) 2,450.00 to 39 Super Deluxe (single 034-433-72- 81 or double) 3,080.00 Matrimonial Room 3,500.00 L' Fisher Chalet Budget Room 1,500.00 Economy 2pax 1,900.00 Economy 3pax 2,610.00 Standard Room 2pax 2,250.00 Standard Room 3pax 2,960.00 Family Room (4) 4,100.00 034-432-36- Saltimboca Tourist & Rest. 15th Lacson St. Bacolod City 17 Standard Room A 800.00 034-433-31- ( fronting L' Fisher Hotel) 79 Satndard Room B 770.00 Std. Room C 600.00 Std. Room D 900.00 Garden Executive 1,300.00 Deluxe 1 1,000.00 Deluxe 2 1,000.00 Single Room 1 695.00 Single Room 2 550.00 Blue Room 900.00 Family Room 1,400.00 extra person/bed 150.00/150.00 034-433-33- Pension Bacolod & Rest. No. 27, 11th St. Bacolod City 77 Single w/ tv & aircon. 540.00 034-432-32- (near L' Fisher Hotel) 31 Dble w/ TV & aircon. 670.00 034-433-70- 65 Trple w/ TV & aircon 770.00 034-435-57- Regina Carmeli Pension 13th St. Bacolod City 49 Superior 2 pax, 1 dble bed 700.00 (near L' Fisher Hotel) Superior 2 pax, 2 single beds 750.00 Standard 3 pax 900.00 Deluxe 4 pax 1,350.00 Family 5-6 pax 1,500.00 11th Street Bed & Breakfast 034-433-91- Inn No. -

Hotels Near Duke: Ask for the Duke Rate $$ Inexpensive Or Below $100 Per Night $$$ Average Or Below $150 Per Night $$$$ Expensive Or Over $200 Per Night

Hotels near Duke: Ask for the Duke Rate $$ Inexpensive or below $100 per night $$$ Average or below $150 per night $$$$ Expensive or over $200 per night HOTELS WITHIN WALKING DISTANCE TO DUKE Cambria Hotel & Suites Durham ($$) www.cambriadurham.com 2306 Elba Street, Durham, NC 27705 T: 919.286.3111 Shuttle to/from Duke (6am – 9:30pm weekdays, 9am - 4:30pm Saturdays). Located across the street from Medical Center and Duke’s West Campus. Coin-operated washer/dryer on the premises, WiFi, microwave, refrigerator, and fitness center. Free parking. Hilton Garden Inn Durham/University Medical Center ($$$) http://hiltongardeninn3.hilton.com/en/hotels/north-carolina/hilton-garden-inn-durham-university- medical-center-RDUMCGI/index.html 2102 West Main Street, Durham, NC 27705 T: 919.286.0774 Shuttle available within a 5-mile radius of hotel (6:30am – 9:30pm everyday). Fitness Center and Pool. Has a restaurant that serves breakfast and dinner. WiFi, microwave, & refrigerator in room. Millennium Hotel Durham ($$) https://www.millenniumhotels.com/en/durham/millennium-hotel-durham/?cid=gplaces-MilDurham 2800 Campus Walk Avenue, Durham, NC 27705 T: 919.383.8575 Restaurant, indoor pool and fitness center on the premises. Shuttle to/ from RDU airport (ask ahead as it depends if they have drivers). $40/person one-way charge. Shuttle to/from Duke. 7am – 10pm daily. $6/room per day charge. Residence Inn: Duke University Medical Center Area ($$$) http://www.marriott.com/hotels/travel/rdudd-residence-inn-durham-mcpherson-duke-university- medical-center-area/ 1108 West Main Street, Durham, NC 27701 T: 919.680.4440 Apartment style suites with full-sized kitchens and living area. -

Resort Weeks Calendar

Resort Weeks Calendar CLUB RESORTS SS—SPECIAL SEASON LS—LEAF SEASON UR—ULTRA RED SEASON HR—HIGH RED SEASON R—RED SEASON CLUB ASSOCIATE RESORTS W—WHITE SEASON B—BLUE SEASON January February March April May June July August September October November December ARIZONA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 Cibola Vista Resort and Spa ALABAMA Paradise Isle Resort Shoreline Towers ARUBA La Cabana Beach Resort & Casino CALIFORNIA The Club at Big Bear Village COLORADO The Innsbruck Aspen FLORIDA GULF COAST Bluegreen at Tradewinds Landmark Holiday Beach Resort Mariner’s Boathouse & Beach Resort Ocean Towers Beach Club Panama City Resort & Club Resort Sixty-Six Surfrider Beach Club Tropical Sands Resort Via Roma Beach Resort Winward Passage Resort CENTRAL FLORIDA Casa Del Mar Beach Resort Daytona SeaBreeze Dolphin Beach Club Fantasy Island Resort II The Fountains Grande Villas at World Golf Village Orlando’s Sunshine Resort—Phase I Orlando’s Sunshine Resort—Phase II Outrigger Beach Club SOUTH FLORIDA & THE KEYS Gulfstream Manor The Hammocks at Marathon Solara Surfside GEORGIA The Studio Homes at Ellis Square Petit Crest & Golf Club Villas at Big Canoe HAWAII Pono Kai Resort ILLINOIS Hotel Blake LOUISIANA Bluegreen at Club La Pension The Marquee MASSACHUSETTS The Breakers Resort The Soundings at Seaside Resort MICHIGAN Mountain Run at Boyne MISSOURI The Falls Village Paradise Point Bluegreen Wilderness Club at Big Cedar The Cliffs at Long -

Public Pension Human Resources Organization

PUBLIC PENSION HUMAN RESOURCES ORGANIZATION ROUNDTA B L E 2 0 1 4 O C T O B E R 7 - 8 2 0 1 4 RENAISSANCE SEATTLE HOTEL SEATTLE, WASHINGTON The Public Pension Human Resources Organization Roundtable draws together Human Resources professionals from Public Pension funds throughout the country to learn from industry experts, discuss current issues, and share best practices and ideas from their organizations. Special thanks for coordinating the Roundtable goes to: PUBLIC PENSION HR ORGANIZATION ROUN D T A B L E 2014 AGENDA TUESDAY, OCTOBER 7 8:30—9:00 am Continental Breakfast 9:00—9:15 am Welcome 9:15 —10:15 am What’s Happening in Washington? Neil E. Reichenberg • Executive Director, IPMA-HR Neil will provide us an update on legislative issues in Washington that may affect the HR practice. 10:15—10:30 am Break 10:30—11:00 am Wait...What? A Discussion on Developments in the HR Certification World Neil E. Reichenberg • Executive Director, IPMA-HR 11:00 am—12:00 pm “Open Mic”: Discussion of Critical HR Issues at Each Fund This is your opportunity to gain insight and feedback from experienced colleagues on critical HR is- sues affecting your fund. If you need input, come prepared to present your concern. Topics may in- clude issues within the HR body of knowledge, such as benefits, compensation, employee relations, leadership development, recruiting, etc. 12:00—1:00 pm Lunch (included in conference fee) 1:00—2:00 pm Practitioner Presentation: Building a Constructive Culture Within an Investment Shop Mika Austin • General Manager Human Resources, New Zealand Superannuation Fund The New Zealand Superannuation Fund has been on a mission over the last 3-4 years to turn their culture around towards a collaborative, constructive, truly integrated team approach. -

Proclamation No.152 /2006 the Tourism Proclamation

Proclamation No.152 /2006 The Tourism Proclamation Article 1. Short Title This Proclamation may be cited as “the Tourism Proclamation No.152/2006”. Article 2. Definitions, In this Proclamation, unless the context otherwise requires: (1) “hotel” means an establishment or place, which provides to tourists for fee or reward sleeping accommodation with or without food or beverage and which has no less than ten bedrooms; (2) “tourist supplementary accommodation establishment” means a pension, resort, family pension, a motel, a guest house or furnished apartment a holiday village and a village inn which provides accommodation with or without food or beverages for tourists in return for payment. (3)“restaurant and food catering establishments” means restaurants, buffets, snack bars, tearooms, table d’ hôte, fast food facilities and catering services; (4)“tourist boat” means a pleasure boat available for the transport of tourists for fishing as a sport, for water-sports or pleasure generally; (5)“tourist transport provider” means a person engaged in providing transportation to tourists by means of motor vehicles, including rental of cars, railway, marine vessels of 26 meters length and other means of tourist transportation as prescribed by regulations; (6) “tourist” means a person who stays at least one night in Eritrea, in either private or commercial accommodation, but whose stay does not exceed twelve months and whose main purpose of visit is not to work; (7) “tourism” means the business of providing travel, accommodation, hospitality and -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: September

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: September 22, 2020 CONTACT: Samuel Johnson, General Manager, Oxford Hotel Bend, [email protected] HIGH RES IMAGES: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/xrh2afxzf78oxo3/AABUr2rAnrA5VunOUS8Fmr9Va?dl=0 OXFORD HOTEL BEND VOTED BEST LODGING IN CENTRAL OREGON Bend, Ore. – The Oxford Hotel Bend has once again been voted the top lodging spot in the Source Weekly’s Best of Central Oregon. This marks the ninth year the hotel has received this honor. Winners and runner-ups in over 140 categories were announced in the Source’s September 17th issue, highlighting the top voted businesses, services, and attractions across Central Oregon. “We want to sincerely thank our Bend community for again voting us best lodging in Central Oregon,” said Samuel Johnson, General Manager of Oxford Hotel Bend. “It’s an honor to receive this news, especially with the uncertainty this year has held. We are grateful to be able to call Bend home—we love being a part of this wonderful community, and it's a real honor to know that the feeling is mutual. We want to say thank you to everyone that voted and to the Source Weekly for fostering so much positivity during this time.” Opened in 2010, the locally owned and operated Oxford Hotel Bend has been a prominent asset to the Central Oregon hospitality industry, offering an upscale travel experience to visitors. The hotel was recently recognized as the #6 Best Hotel in the United States in Tripadvisor’s Travelers’ Choice awards. Curt and Robin Baney, owners of the Oxford Collection of hotels, parent company of Oxford Hotel Bend, have consistently been committed to the enrichment of the community, evident in their generous contributions to the OSU-Cascades endowed faculty fund for its hospitality management program in 2016 and 2018. -

Luxury Boutique Hotels – a Growing Concept in India

Sep 28 2020 Luxury Boutique Hotels – a growing concept in India Luxury boutique hotels and resorts, a widely prevalent concept globally, is still at a nascent stage in India, with very few brands and properties. The increasing desire for experiential travel, by not only the millennials but across different cohorts often looking for unique and exclusive stays, has led to the growing popularity of this concept in the country. So, what are luxury boutique hotels and resorts? The term has evolved over the years, and while there is no standard definition, a luxury boutique hotel is typically a small property with less than 60 keys with its USP being the customized service and ‘elevated experience’ provided to guests. The differentiated experience is often a result of various factors such as the location, design, architecture or even the specially curated theme or events at the property that provides the guests with a unique story and memory. The luxury boutique segment is expected to become an increasingly preferred choice in the post-COVID era as people rediscover the pleasures of traveling but are still cautious with safety, cleanliness and privacy being their top priorities. These hotels are best positioned to leverage this demand by gaining guest confidence and trust due to their smaller size, with lesser number of rooms and smaller public places. • Luxury boutique resorts can help in tapping the full potential of leisure tourism in India. There are several unexplored and underdeveloped beaches, wildlife sanctuaries, heritage sites and hill stations in India which can be developed into established leisure destinations but are lagging due to lack of quality accommodation. -

List of Hotels Registered

LIST OF HOTELS REGISTERED Conference Hall Sl. Dzongkhag Star Rating No. Capacity Bumthang 1 Yu-Gharling Resort 3 100 2 Rinchenling Resort 3 45 3 Yozerling Lodge 3 40-45 4 Dekyil GuestHouse 3 25 5 Happy Garden Lodge Budget 40-50 6 Kaila Guest House 3 50 7 Tashi Yangkhil Budget 25 8 Phuntsho Guest House 3 9 Hotel Ugyenling 3 10 Swiss Guest House 3 30 11 Tashi Yoezerling 3 25-30 12 Gatseling Budget 20 13 Samyae Resort 3 14 Bumthang Guest House Budget 15 Mountain Resort 3 75/25(2 nos) 16 Wangdi Choling Resort 3 60-70 17 River lodge 3 50 18 Jakar Village lodge 3 25-30 19 Hotel Jakar View 3 26 20 Chumey Nature Restort 3 30 Haa 1 Jampelyang Hotel 3 50 2 Haa Heritage Hotel 3 40 3 Sonam Zhidey resort 3 50 4 Soednam Zhigkha Heritage 3 40 5 Blue Pine Food and Lodge Budget 6 Risum Resort 3 45 7 Hotel Lhayul 3 40 8 Taag Sing Chung Druk Budget 9 Rikey Restaurant Budget Samtse 1 Hotel Kuendhen Budget 50 person Page 1 List of Hotels registered as on 30/4/21. For further details please call the respective Dzongkhag focal Officers given below. Conference Hall Sl. Dzongkhag Star Rating No. Capacity Thimphu 1 Jambayang Resort 3 45 capacity (2 Nos) 2 Hotel Mayto 3 20 capacity 3 Lhaki Yangchak Residency 3 50/15 capacity(2 no) 4 The Pema by Realm 4 30 capacity (2 no) 5 Reaso Hotel Standard 32 capacity 6 Tashi Yeodling 3 35/25 capacity (1 no) 7 Ludrong Hotel 3 35/20 capacity(1 no.) 8 Norkhil Boutique Hotel and SPA 4 25-35 capacity (1 no.) 9 Tara Phendeyling 3 35 capacity (1 no) 10 Kuenden Boutique Hotel 3 30/15 capacity (2 nos.) 11 Institute of Management Studies -

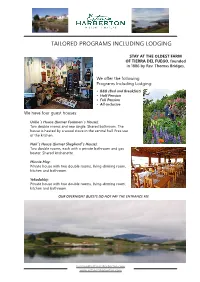

Tailored Programs Including Lodging

TAILORED PROGRAMS INCLUDING LODGING STAY AT THE OLDEST FARM OF TIERRA DEL FUEGO, founded in 1886 by Rev. Thomas Bridges. We offer the following Programs Including Lodging: • B&B (Bed and Breakfast) • Half Pension • Full Pension • All-inclusive We have four guest houses: Uribe´s House (former Foreman´s House): Two double rooms and one single. Shared bathroom. The house is heated by a wood stove in the central hall. Free use of the kitchen. Nail´s House (former Shepherd´s House): Two double rooms, each with a private bathroom and gas heater. Shared kitchenette. Minnie May: Private house with two double rooms, living-dinning room, kitchen and bathroom. Yekadahby: Private house with two double rooms, living-dinning room, kitchen and bathroom. OUR OVERNIGHT GUESTS DO NOT PAY THE ENTRANCE FEE [email protected] www.estanciaharberton.com THE DIFFERENT OPTIONS OF TAILORED PROGRAMS INCLUDING LODGING WE OFFER ARE: Bed and Breakfast Program • Simple breakfast, left at the house the previous night. • Free use of kitchen or kitchenette (depending on the house chosen). • Step back in time during the walking tour of Harberton homes- tead, a National Historical Monument, within regular tour hours. This tour includes the history of the Bridges family and their relationship with the natives, the Park (first nature reserve of Tierra del Fuego), the family cemetery, replicas of yahgan huts, the old-time shearing shed, carpenter´s shop, the boat house (which houses the second oldest boat built in Tierra del Fuego) and the beautiful Main House garden. • Immerse yourself in the depths of the sea during the guided tour of the singular Acatushun Bird and Marine Mammal Museum, within regular tour hours. -

Technical Note Alliance Against Trafficking in Persons

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings TECHNICAL NOTE ALLIANCE AGAINST TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS An Agenda for Prevention: Non-Discrimination and Empowerment Thursday 11 and Friday 12 October 2012 Vienna, Hofburg Venue The 12th High-level Alliance Against Trafficking in Persons conference entitled “An Agenda for Prevention: Non-Discrimination and Empowerment” will take place on Thursday 11 and Friday 12 October 2012 at the OSCE premises in the Hofburg Congress Center, Heldenplatz, A-1600 Vienna. For more information on access to Vienna and to the conference premises, please see the next page of this technical note. Please note that access to the OSCE premises is permitted only on presentation of a photo ID card (passport, national ID card or driver’s licence) in accordance with lists notified in advance (see below). Language The meeting will be held in English with simultaneous interpretation from/to English, Italian and Russian, French, German and Spanish. Registration Participants are kindly requested to fill out the registration form, specifying their affiliation, and return it by email to Ms. Elke Lidarik, < [email protected] > no later than Friday 28 September 2012. Please note that the registration is only definite upon receipt of a confirmation email from the OSCE. Visas Visa support letters can be requested by email to Elke Lidarik < [email protected] >. Please note that visas will only be granted for the period of the seminar and that your request should be accompanied by a passport copy. Document Distribution Participating States who wish to distribute documents are requested to send these materials in electronic format to the OSCE Office of the Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings < [email protected] >, by Friday 28 September 2012. -

Pension Reform Draft

UNOFFICIAL COPY 17 SS BR 10 AN ACT relating to retirement. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky: SECTION 1. A NEW SECTION OF KRS CHAPTER 61 IS CREATED TO READ AS FOLLOWS: (1) The General Assembly finds and determines that: (a) It is the intent of the General Assembly to establish and preserve a necessary and proper balance between promoting the general welfare and material well-being of the citizens of the Commonwealth and meeting the commitments made to the state’s current and future public sector employees and retirees; (b) The general welfare and material well-being of the citizens of the Commonwealth depend upon adequate funding for investments in vital public services, including but not limited to elementary, secondary, and postsecondary education, health care and public health services, public safety and public protection, roads and infrastructure, and economic development initiatives; (c) The funding requirements to support the Commonwealth’s current public pension systems are unsustainable and severely constrain the capacity of state and local budgets to allocate adequate funding to support vital public services and thereby undercut the General Assembly’s goal to promote the general welfare and material well-being of the citizens of the Commonwealth; (d) The crowding-out of investments in vital public services due to the unsustainable growth in the state’s pension systems' funding requirements makes the Commonwealth less attractive for private sector investment, which in turn hinders the economic