A Brief for the Defense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies in Applied Economics

SAE./No.128/October 2018 Studies in Applied Economics THE BANK OF FRANCE AND THE GOLD DEPENDENCY: OBSERVATIONS ON THE BANK'S WEEKLY BALANCE SHEETS AND RESERVES, 1898-1940 Robert Yee Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise The Bank of France and the Gold Dependency: Observations on the Bank’s Weekly Balance Sheets and Reserves, 1898-1940 Robert Yee Copyright 2018 by Robert Yee. This work may be reproduced or adapted provided that no fee is charged and the proper credit is given to the original source(s). About the Series The Studies in Applied Economics series is under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of The Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise. About the Author Robert Yee ([email protected]) is a Ph.D. student at Princeton University. Abstract A central bank’s weekly balance sheets give insights into the willingness and ability of a monetary authority to act in times of economic crises. In particular, levels of gold, silver, and foreign-currency reserves, both as a nominal figure and as a percentage of global reserves, prove to be useful in examining changes to an institution’s agenda over time. Using several recently compiled datasets, this study contextualizes the Bank’s financial affairs within a historical framework and argues that the Bank’s active monetary policy of reserve accumulation stemmed from contemporary views concerning economic stability and risk mitigation. Les bilans hebdomadaires d’une banque centrale donnent des vues à la volonté et la capacité d’une autorité monétaire d’agir en crise économique. -

Table 1 ΠCENTRAL BANK STATUORTY GOLD RESERVE REQUIREMENTS

Appendix 3. Central Bank Gold Reserve Statutes Table 1 – CENTRAL BANK STATUTORY GOLD RESERVE REQUIREMENTS UNDER THE CLASSICAL GOLD STANDARD (1880 – 1914) COUNTRY LEGAL RESERVE REQUIREMENTS Argentina – Currency Board 1899 1913 Australia 25% in gold on bank notes up to £7,000,000, 100% above that (law of 1910). Before 1910 no government notes, no legal reserve requirements on commercial bank notes. Belgium 33 1/3% on notes and other demand liabilities Brazil 33 1/3% in gold on note issue (Act of 1890); 100% in gold and convertible securities: Currency Board (1906-1914) Canada 25% on Dominion notes in excess of 20 million. No legal reserve requirements on chartered banks. Chile None Denmark 37.5% in gold coin or bullion on notes until 1907; thereafter 50%. Finland maximum uncovered note issue of 40,000,000 marks, 100% cover in gold, foreign exchange above that France None Germany 33 1/3% in gold coin or bullion on note liabilities Greece 3 1/3% in gold coin or bullion on notes Italy 40% in gold or silver on notes Japan on note liability in gold coin or bullion in excess of fiduciary issue of 120,000,000 yen (1899) Netherlands 40% in gold coin on notes and deposits Norway on note liabilities, 100% in gold coin or bullion in excess of fiduciary issue of 35,000,000 crowns Table 1 – CENTRAL BANK STATUTORY GOLD RESERVE REQUIREMENTS UNDER THE CLASSICAL GOLD STANDARD (1880 - 1914) COUNTRY LEGAL RESERVE REQUIREMENTS Portugal 33 1/3% in gold coin or bullion on note circulation and demand liabilities Spain 33 1/3% cash reserve on a maximum note issue of 1,500,000 pesetas, at least one half to be held in gold Sweden 40 million kroner in gold on notes Switzerland 40% in gold coin on notes United Kingdom 100% in gold coin or bullion on notes in excess of fiduciary issue (£ 14 million plus two - third of lapsed bank notes) United States as of 1900, Treasury minimum of 100 million in gold coin Sources: Germany, Sweden, Italy in Michael D. -

The Gold Pool (1961-1968) and the Fall of the Bretton Woods System

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE GOLD POOL (1961-1968) AND THE FALL OF THE BRETTON WOODS SYSTEM. LESSONS FOR CENTRAL BANK COOPERATION. Michael Bordo Eric Monnet Alain Naef Working Paper 24016 http://www.nber.org/papers/w24016 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2017 The views expressed in this paper do not represent the opinion of the Banque de France, Eurosystem, or the National Bureau of Economic Research. We thank the archivists of the Bank for International Settlements, the Bank of England, the New York Fed and the Banque de France for their help. Piet Clement kindly shared by email some additional documents. Kathleen Rasmussen guided us to the US Department of State online archives. We are grateful to seminar participants at the University Paris 1 Sorbonne, the credit, currency and commerce conference (University of Cambridge), Saint Louis Fed and World Cliometrics Congress for comments. We are indebted to Owen Humpage, Walter Jansson and Catherine Schenk for comments on previous drafts. We also thank David Chambers for sharing data. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Michael Bordo, Eric Monnet, and Alain Naef. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Gold Pool (1961-1968) and the Fall of the Bretton Woods System. Lessons for Central Bank Cooperation. -

The Guide to Mining Arbitrations

Global Arbitration Review The Guide to Mining Arbitrations Editors Jason Fry and Louis-Alexis Bret © 2019 Law Business Research Ltd The Guide to Mining Arbitrations Editors Jason Fry and Louis-Alexis Bret Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd This article was first published in June 2019 For further information please contact [email protected] arg © 2019 Law Business Research Ltd Publisher David Samuels Business Development Manager Gemma Chalk Editorial Coordinator Hannah Higgins Head of Production Adam Myers Production editor Harry Turner Copy-editor Gina Mete Proofreader Rakesh Rajani Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London 87 Lancaster Road, London, W11 1QQ, UK © 2019 Law Business Research Ltd www.globalarbitrationreview.com No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although the information provided is accurate as of May 2019, be advised that this is a developing area. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to Law Business Research, at the address above. Enquiries concerning editorial content should be directed to the Publisher – [email protected] ISBN 978-1-83862-206-0 Printed in Great -

The Price of Gold

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE No. 15, July 1952 THE PRICE OF GOLD MIROSLAV A. KRIZ INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION 1.DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Princeton, New1 Jersey This is the fifteenth in the series ESSAYS IN INTER- NATIONAL FINANCE published by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics and Social Institutions in Princeton University. It is the second in the series written by the present author, the first one, "Postwar International Lending," having been published in the spring of 1947 and long since out of print. The author, Miroslav A. Kriz, is on the staff of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. From 1936 to 1945 he was a member of the Economic and Fi- nancial Department of the League of Nations. While the Section sponsors the essays in this series, it takes no further responsibility for the opinions therein expressed. The writers are free to develop their topics as they, will and their ideas may or may not be shared by the .editorial committee of the Sec- tion or the members of the Department. Nor do the views _the writer expresses purport to reflect those of the institution with which he is associated. The Section welcomes the submission of manu- scripts for this series and will assume responsibility for a careful reading of them and for returning to the authors those found unacceptable for publication. GARDNER PATTERSON, Director International Finance Section THE PRICE OF GOLD MIROSLAV A: KRIZ Federal Reserve Bank of New Y orki I. INTRODUCTION . OLD in the world today has many facets. -

Precious Metals Prices Soar! U.S

Volume 13 Issue 11 Liberty Coin Service’s Monthly Review of Precious Metals and Numismatics October 31, 2007 As Central Bank Gold Price Suppression Conspiracy Falls Apart— Precious Metals Prices Soar! U.S. Dollar Falls To Record Low—Further Declines Expected Will Gold Reach $1,300 And Silver $22 By April 2008? There has been a flurry of revelations and from current levels. 2007 Year To Date Results new developments in the past month that Here are some of the recent developments Through October 30, 2007 just about all point to the falling value of that lead me to these conclusions. Precious Metals currencies in general and the U.S. dollar in News And Information You Platinum +26.4% particular. Gold +23.5% The prices of gold and silver have May Have Missed 1) When bureaucrats have to reveal Silver +11.2% climbed significantly as a result. Palladium +10.5% With only limited space in this newslet- something they would prefer remain un- ter, I can only cover some of the items and known and obscure, they can become ex- Numismatics MS-63 $20.00 Liberty +24.3% not go into the depth that they deserve. perts at burying the disclosure in the middle MS-63 $20.00 St Gaudens +23.5% But, uniformly, they lead me to the conclu- of lengthy reports. Sometimes, it takes a while before anyone catches on. MS-65 Morgan Dollar -3.3% sions that: The past coordinated efforts among a For example, on May 14 the U.S. Treas- US Dollar vs Foreign Currencies number of central banks, international ury’s weekly report of the U.S. -

Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Foreign Exchange Reserve

Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Foreign Exchange Reserve Management 2018 Foreign Exchange Reserve Management Contents 1 PREFACE 2 2 DEFINITION OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVE 2 3 LEGAL FRAMEWORK 3 4 INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK 3 5 TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY 4 6 FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVE MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGY 4 7 TYPES OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVE MANAGEMENT OPERATIONS 6 8 IMPLEMENTATION OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVE MANAGEMENT 7 9 RISK MANAGEMENT 7 9.1 Sources of Risk 7 9.1.1 Market Risk 7 9.1.2 Credit Risk 7 9.1.3 Liquidity Risk 8 9.1.4 Operational Risk 8 9.2 Risk Control 8 9.3 Risk Measurement, Reporting and Monitoring 9 9.4 Performance Evaluation 10 10 RESERVE MANAGEMENT OPERATIONS IN 2017 10 10.1 Reserve Developments in 2017 10 10.2 Investment and Risk Management Process 11 10.3 Investing Activities in 2017 and Composition of Reserves 11 11 OVERVIEW 14 ANNEX 1: MANAGEMENT OF GOLD RESERVES 15 1 Foreign Exchange Reserve Management 1. Preface Foreign exchange (FX) reserves play a significant role in achieving macroeconomic policy targets and preventing possible financial crises in that they provide room for maneuver for the sustainability of the exchange rate regime and monetary policies. Under the fixed exchange rate regime, central banks warranted that the local currency could be converted to foreign currency at a fixed rate, and they held foreign exchange reserves to fulfill this commitment. In the following periods, in line with the developments in the world economy, there was a shift from the fixed exchange rate regime to flexible and floating exchange rate regimes. -

Central Banks and Gold Puzzles

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CENTRAL BANKS AND GOLD PUZZLES Joshua Aizenman Kenta Inoue Working Paper 17894 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17894 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2012 We are grateful for useful comments from an anonymous referee. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Joshua Aizenman and Kenta Inoue. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Central Banks and Gold Puzzles Joshua Aizenman and Kenta Inoue NBER Working Paper No. 17894 March 2012, Revised January 2013 JEL No. E58,F31,F33 ABSTRACT We study the curious patterns of gold holding and trading by central banks during 1979-2010. With the exception of several discrete step adjustments, central banks keep maintaining passive stocks of gold, independently of the patterns of the real price of gold. We also observe the synchronization of gold sales by central banks, as most reduced their positions in tandem, and their tendency to report international reserves valuation excluding gold positions. Our analysis suggests that the intensity of holding gold is correlated with ‘global power’ – by the history of being a past empire, or by the sheer size of a country, especially by countries that are or were the suppliers of key currencies. -

Strained Relations: US Foreign-Exchange Operations and Monetary Policy in the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Strained Relations: U.S. Foreign-Exchange Operations and Monetary Policy in the Twentieth Century Volume Author/Editor: Michael D. Bordo, Owen F. Humpage, and Anna J. Schwartz Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-05148-X, 978-0-226-05148-2 (cloth); 978-0-226-05151-2 (eISBN) Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/bord12-1 Conference Date: n/a Publication Date: February 2015 Chapter Title: Introducing the Exchange Stabilization Fund, 1934–1961 Chapter Author(s): Michael D. Bordo, Owen F. Humpage, Anna J. Schwartz Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c13539 Chapter pages in book: (p. 56 – 119) 3 Introducing the Exchange Stabilization Fund, 1934– 1961 3.1 Introduction The Wrst formal US institution designed to conduct oYcial intervention in the foreign exchange market dates from 1934. In earlier years, as the preceding chapter has shown, makeshift arrangements for intervention pre- vailed. Why the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) was created and how it performed in the period ending in 1961 are the subject of this chapter. After thriving in the prewar years from 1934 to 1939, little opportunity for intervention arose thereafter through the closing years of this period, so it is a natural dividing point in ESF history. The change in the fund’s operations occurred as a result of the Federal Reserve’s decision in 1962 to become its partner in oYcial intervention. A subsequent chapter takes up the evolution of the fund thereafter. -

The Evolution in Central Bank Attitudes Toward Gold About the World Gold Council

THE EVOLUTION IN CENTRAL BANK AttITUDES TOWARD GOLD About The World Gold Council The World Gold Council’s mission is to stimulate and sustain the demand for gold and to create enduring value for its stakeholders. The organisation represents the world’s leading gold mining companies, who produce more than 60% of the world’s annual gold production in a responsible manner and whose Chairmen and CEOs form the Board of the World Gold Council (WGC). As the gold industry’s key market development body, WGC works with multiple partners to create structural shifts in demand and to promote the use of gold in all its forms; as an investment by opening new market channels and making gold’s wealth preservation qualities better understood; in jewellery through the development of the premium market and the protection of the mass market; in industry through the development of the electronics market and the support of emerging technologies and in government affairs through engagement in macro-economic policy issues, lowering regulatory barriers to gold ownership and the promotion of gold as a reserve asset. The WGC is a commercially-driven organisation and is focussed on creating a new prominence for gold. It has its headquarters in London and operations in the key gold demand centres of India, China, the Middle East and United States. The WGC is the leading source of independent research and knowledge on the international gold market and on gold’s role in meeting the social and economic demands of society. 1 The evolution in central bank attitudes toward -

The Elusive Promise of Independent Central Banking Keynote Speech by Marvin Goodfriend

main : 2012/10/30(11:24) The Elusive Promise of Independent Central Banking Keynote Speech by Marvin Goodfriend Independent central banking is reviewed as it emerged first under the gold standard and later with inconvertible paper money. Monetary and credit policy are compared and contrasted as practiced by the 19th century Bank of England and the Federal Reserve. The lesson is that wide operational and financial independence given to monetary and credit policy in the public interest subjects the central bank to incentives detrimental for macroeconomic and financial stability. An independent central bank needs the double discipline of a priority for price stability and bounds on expansive credit initiatives to secure its promise for stabilization policy. Keywords: Bank of England; Central bank independence; Credit turmoil of 2007–08; Federal Reserve; Great Inflation; Lender of last resort; Monetary policy JEL Classification: E3, E4, E5, E6 Professor of Economics, Tepper School of Business, Carnegie Mellon University and National Bureau of Economic Research (E-mail: [email protected]) ......................................................................................................................................................... The paper benefited from the comments of Michael Bordo, Barry Eichengreen, Kenneth Garbade, Robert Hetzel, and Allan Meltzer, and presentations at the Bank of Korea 2012 International Conference, Seoul, South Korea and the Institute for Financial Studies, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu, Sichuan, China. The research was supported by the Gailliot Center for Public Policy at the Tepper School, Carnegie Mellon University. This paper was prepared for the 2012 BOJ-IMES Conference, “Demographic Changes and Macroeconomic Performance,” held by the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies, Bank of Japan, in Tokyo on May 30–31, 2012. -

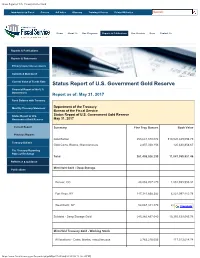

Status Report of U.S. Treasury-Owned Gold

Status Report of U.S. Treasury-Owned Gold Introduction to Fiscal Careers A-Z Index Glossary Training & Events Related Websites Home About Us Our Programs Reports & Publications Our Services News Contact Us Reports & Publications Reports & Statements Privacy Impact Assessments Combined Statement Current Value of Funds Rate Status Report of U.S. Government Gold Reserve Financial Report of the U.S. Government Report as of: May 31, 2017 Fund Balance with Treasury Monthly Treasury Statement Department of the Treasury Bureau of the Fiscal Service Status Report of U.S. Status Report of U.S. Government Gold Reserve Government Gold Reserve May 31, 2017 Current Report Summary Fine Troy Ounces Book Value Previous Reports Gold Bullion 258,641,878.074 $10,920,429,098.79 Treasury Bulletin Gold Coins, Blanks, Miscellaneous 2,857,048.156 120,630,858.67 The Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange Total 261,498,926.230 11,041,059,957.46 Reference & Guidance Mint-Held Gold - Deep Storage Publications Denver, CO 43,853,707.279 1,851,599,995.81 Fort Knox, KY 147,341,858.382 6,221,097,412.78 West Point, NY 54,067,331.379 2,282,841,677.17Translate Subtotal - Deep Storage Gold 245,262,897.040 10,355,539,085.76 Mint-Held Treasury Gold - Working Stock All locations - Coins, blanks, miscellaneous 2,783,218.656 117,513,614.74 https://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/fsreports/rpt/goldRpt/17-05.htm[10/18/2017 1:06:35 PM] Status Report of U.S. Treasury-Owned Gold Subtotal - Working Stock Gold 2,783,218.656 117,513,614.74 Grand Total - Mint-Held Gold 248,046,115.696 10,473,052,700.50 Federal Reserve Bank-Held Gold Gold Bullion: Federal Reserve Banks - NY Vault 13,376,987.715 564,805,850.63 Federal Reserve Banks - display 1,993.319 84,162.40 Subtotal - Gold Bullion 13,378,981.034 564,890,013.03 Gold Coins: Federal Reserve Banks - NY Vault 73,452.066 3,101,307.82 Federal Reserve Banks - display 377.434 15,936.11 Subtotal - Gold Coins 73,829.500 3,117,243.93 Total - Federal Reserve Bank-Held Gold 13,452,810.534 568,007,256.96 Total - U.S.