Amy Brancolli, “'Brokeback Mountain': a Tragedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beneficence of Gayface Tim Macausland Western Washington University, [email protected]

Occam's Razor Volume 6 (2016) Article 2 2016 The Beneficence of Gayface Tim MacAusland Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation MacAusland, Tim (2016) "The Beneficence of Gayface," Occam's Razor: Vol. 6 , Article 2. Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu/vol6/iss1/2 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occam's Razor by an authorized editor of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MacAusland: The Beneficence of Gayface THE BENEFICENCE OF GAYFACE BY TIM MACAUSLAND In 2009, veteran funny man Jim Carrey, best known to the mainstream within the previous decade with for his zany and nearly cartoonish live-action lms like American Beauty and Rent. It was, rather, performances—perhaps none more literally than in that the actors themselves were not gay. However, the 1994 lm e Mask (Russell, 1994)—stretched they never let it show or undermine the believability his comedic boundaries with his portrayal of real- of the roles they played. As expected, the stars life con artist Steven Jay Russell in the lm I Love received much of the acclaim, but the lm does You Phillip Morris (Requa, Ficarra, 2009). Despite represent a peculiar quandary in the ethical value of earning critical success and some of Carrey’s highest straight actors in gay roles. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

Case 1:07-cv-00098-RMU Document 52 Filed 11/15/07 Page 1 of 10 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA JANICE SCOTT-BLANTON, : : Plaintiff, : Civil Action No.: 07-0098 (RMU) : v. : Document Nos.: 30, 32 : UNIVERSAL CITY STUDIOS : PRODUCTIONS LLLP et al., : : Defendants. : MEMORANDUM OPINION DENYING THE PLAINTIFF’S MOTION TO PERMIT DISCOVERY PURSUANT TO RULE 56(F) I. INTRODUCTION The plaintiff, Janice Scott-Blanton, proceeding pro se, alleges that her novel, My Husband Is On The Down Low and I Know About It (“Down Low”), is the creative source for the award-winning film Brokeback Mountain. She requests that the court permit discovery pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(f), because it would be premature for the court to decide the defendants’ outstanding motion for summary judgment without a period of discovery. While the plaintiff identifies specific facts she seeks to recover in discovery that would defeat the defendants’ summary judgment motion, she fails to show a reasonable basis to suggest that discovery would create a triable issue of fact. As a result, the court denies the plaintiff’s motion to permit discovery. Case 1:07-cv-00098-RMU Document 52 Filed 11/15/07 Page 2 of 10 II. BACKGROUND A. Factual History Annie Proulx (“Proulx”) wrote the short story Brokeback Mountain in 1997, which The New Yorker published and registered for copyright protection in October of that year. Am. Compl. ¶ 38; Decl. of Marc E. Mayer (“Mayer”) (D.D.C. Mar. 7, 2007) (“Mayer Decl.”), Ex. A. Shortly thereafter, Proulx agreed to allow two screenwriters, Diana Ossana and Larry McMurtry, to adapt the story into a screenplay. -

Sherlock Holmes

sunday monday tuesday wednesday thursday friday saturday KIDS MATINEE Sun 1:00! FEB 23 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 24 & 25 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 26 & 27 (3:00 & 7:00 & 9:15) KIDS MATINEE Sat 1:00! UP CLOUDY WITH A CHANCE OF MEATBALLS THE HURT LOCKER THE DAMNED PRECIOUS FEB 21 (3:00 & 7:00) Director: Kathryn Bigelow (USA, 2009, 131 mins; DVD, 14A) Based on the novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire FEB 22 (7:00 only) Cast: Jeremy Renner Anthony Mackie Brian Geraghty Ralph UNITED Director: Lee Daniels Fiennes Guy Pearce . (USA, 2009, 111 min; 14A) THE IMAGINARIUM OF “AN INSTANT CLASSIC!” –Wall Street Journal Director: Tom Hooper (UK, 2009, 98 min; PG) Cast: Michael Sheen, Cast: Gabourey Sidibe, Paula Patton, Mo’Nique, Mariah Timothy Spall, Colm Meaney, Jim Broadbent, Stephen Graham, Carey, Sherri Shepherd, and Lenny Kravitz “ENTERS THE PANTEHON and Peter McDonald DOCTOR PARNASSUS OF GREAT AMERICAN WAR BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS MO’NIQUE FILMS!” –San Francisco “ONE OF THE BEST FILMS OF THE GENRE!” –Golden Globes, Screen Actors Guild Director: Terry Gilliam (UK/Canada/France, 2009, 123 min; PG) –San Francisco Chronicle Cast: Heath Ledger, Christopher Plummer, Tom Waits, Chronicle ####! The One of the most telling moments of this shockingly beautiful Lily Cole, Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell, and Jude Law Hurt Locker is about a bomb Can viewers who don’t know or care much about soccer be convinced film comes toward the end—the heroine glances at a mirror squad in present-day Iraq, to see Damned United? Those who give it a whirl will discover a and sees herself. -

The Color Purple: Shug Avery and Bisexuality

Reading Bisexually Acknowledging a Bisexual Perspective in Giovanni’s Room, The Color Purple, and Brokeback Mountain Maiken Solli A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master’s Degree UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring Term 2012 II Reading Bisexually: Acknowledging a Bisexual Perspective in Giovanni’s Room, The Color Purple, and Brokeback Mountain By Maiken Solli A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master’s Degree Supervisor: Rebecca Scherr UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring Term 2012 III IV © Maiken Solli 2012 Reading Bisexually: The Importance and Significance of Acknowledging a Bisexual Perspective in Fictional Literature Maiken Solli Supervisor: Rebecca Scherr http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo V Abstract In literary theory, literary criticism and in the Western literary canon there is evidence of an exclusion or erasure of a bisexual perspective, and this has also been the case within much of the written history of sexuality and theory, relating to gender, sexuality and identity. This thesis examines and analyses three literary classics; ‘Giovanni’s Room’ by James Baldwin, Alice Walker’s ‘The Color Purple,’ and ‘Brokeback Mountain’ by Annie Proulx, from a bisexual perspective. I have sought out to reveal, emphasize, and analyze bisexual elements present in the respective texts from a bisexual literary standpoint. This aspect of the texts has been ignored by most critics, and I believe it is paramount to begin to acknowledge the importance and significance of reading bisexually. -

JULIA CARTA Hair Stylist and Make-Up Artist

JULIA CARTA Hair Stylist and Make-Up Artist www.juliacarta.com PRESS JUNKETS/PUBLICITY EVENTS Matt Dillon - Grooming - WAYWARD PINES - London Press Junket Jeremy Priven - Grooming - BAFTA Awards - London Christian Bale - Grooming - AMERICAN HUSTLE - BAFTA Awards - London Naveen Andrews - Grooming - DIANA - London Press Junket Bruce Willis and Helen Mirren - Grooming - RED 2 - London Press Conference Ben Affleck - Grooming - ARGO - Sebastián Film Festival Press Junket Matthew Morrison - Grooming - WHAT TO EXPECT WHEN YOU’RE EXPECTING - London Press Junket Clark Gregg - Grooming - THE AVENGERS - London Press Junket Max Iron - Grooming - RED RIDING HOOD - London Press Junket and Premiere Mia Wasikowska - Hair - RESTLESS - Cannes Film Festival, Press Junket and Premiere Elle Fanning - Make-Up - SUPER 8 - London Press Junket Jamie Chung - Hair & Make-Up - SUCKERPUNCH - London Press Junket and Premiere Steve Carell - Grooming - DESPICABLE ME - London Press Junket and Premiere Mark Strong and Matthew Macfayden - Grooming - Cannes Film Festival, Press Junket and Premiere Michael C. Hall - Grooming - DEXTER - London Press Junket Jonah Hill - Grooming - GET HIM TO THE GREEK - London Press Junket and Premiere Laura Linney - Hair and Make-Up - THE BIG C - London Press Junket Ben Affleck - Grooming - THE TOWN - London and Dublin Press and Premiere Tour Andrew Lincoln - Grooming - THE WALKING DEAD - London Press Junket Rhys Ifans - Grooming - NANNY MCPHEE: THE BIG BANG (RETURNS) - London Press Junket and Premiere Bruce Willis - Grooming - RED - London -

Michael Mirasol, “A Great Love Story: 'Brokeback Mountain,'” Chicago Sun-Times, July 1, 2011

Michael Mirasol, “A Great Love Story: ‘Brokeback Mountain,’” Chicago Sun-Times, July 1, 2011 http://blogs.suntimes.com/foreignc/2011/07/brokeback-mountain.html What's the last great love story you've seen on film? I don't mean your typical "rom-coms" with contrived meet-cutes that rely heavily on celebrity star power. I'm talking about a genuine romance between two richly defined characters. If your mind draws a blank, you're not alone. Hollywood, along with much of the filmmaking world, seems to have either forgotten how to portray love affairs in ways that once made us swoon. Whatever the reason, be it due to our changing times or priorities, we might not see any significant ones for some time. If there is any love story of this kind worth revisiting, it is Ang Lee's BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN, which just might be the most moving tale of star-crossed lovers for the past decade. Not many people will remember the film this way, as its two lovers were hardly the kind seen before in major movie romances. Indeed, a story of two cowboys discovering a deep love for each other was bound to cause controversy. Who would dare take on such a subject? Were its motives exploitative? Political? A gimmick? Add in Ang Lee, the celebrated Taiwanese-born director known for ushering the new age of Sino-Cinema to Hollywood, and expectations could not possibly grow further. But grow they did. Once the film won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, a prestige not taken lightly in film circles, interest surged. -

Denis Villeneuve Director / Screenwriter ————— FILMOGRAPHY

Denis Villeneuve Director / Screenwriter ————— FILMOGRAPHY Blade Runner 2049 To be released October 6, 2017 Feature film Director Dune in development Feature film Director The Son in development Feature film Director Arrival 2016 Feature film Director AWARDS Academy Awards - Won Oscar Best Achievement in Sound Editing Sylvain Bellemare - Nominated Oscar Best Motion Picture of the Year Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder, David Linde/ Best Achievement in Directing Denis Villeneuve/ Best Adapted Screenplay Eric Heisserer/ Best Achievement in Cinematography Bradford Young/ Best Achievement in Film Editing Joe Walker/ Best Achievement in Sound Mixing Bernard Gariépy Strobl, Claude La Haye/ Best Achievement in Production Design Patrice Vermette (production design), Paul Hotte (set decoration), 2017, USA BAFTA Awards - Won, BAFTA Film Award Best Sound Claude La Haye, Bernard Gariépy Strobl, Sylvain Bellemare/ Nominated BAFTA Film Award Best Film Dan Levine, Shawn Levy, David Linde, Aaron Ryder/ Best Leading Actress Amy Adams/ Nominated David Lean Award for Direction Denis Villeneuve/ Nominated, BAFTA Film Award Best Screenplay (Adapted) Eric Heisserer/ Best Cinematography Bradford Young/ Best Editing Joe Walker/ Original Music Jóhann Jóhannsson/ Best Achievement in Special Visual Effects Louis Morin, UK, 2017 AFI Awards – Won AFI Awards for Movie of the Year, USA, 2017 ARRIVAL signals cinema's unique ability to bend time, space and the mind. Denis Villeneuve's cerebral celebration of communication - fueled by Eric Heisserer's monumental script - is grounded in unstoppable emotion. As the fearless few who step forward for first contact, Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner and Forest Whitaker prove the imperative for finding a means to connect - with awe- inspiring aliens, nations in our global community and the knowledge that even the inevitable loss that lies ahead is worth living. -

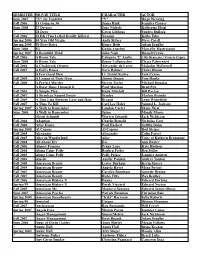

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Brokeback Mountain,” Salon, Dec

Stephanie Zacharek, “Brokeback Mountain,” Salon, Dec. 9, 2005 http://entertainment.salon.com/2005/12/09/brokeback_2/ The premise of Ang Lee’s “Brokeback Mountain,” based on an Annie Proulx short story, is something we’ve never seen before in a mainstream picture: In 1963 two young cowboys meet on the job and, amid a great deal of confusion and denial, as well as many fervent declarations of their immutable heterosexuality, fall in love. Their names — straight out of a boy’s adventure book of the 1930s, or maybe just the result of a long think on the front porch at some writers’ colony — are Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal) and Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger). The attraction between Jack and Ennis is at first timid and muted, the sort of thing that might have amounted to nothing more than a vague, sleep-swollen fantasy. But when they finally give in to that attraction, in a cramped tent out in rural Wyoming — the sheep they’re supposed to be guarding are far off on a hillside, most likely being circled by lip-smacking coyotes — the very sound of their urgent unbuckling and unzipping is like a ghost whistling across the plains, foretelling doom and pleasure and everything in between. This early section of “Brokeback Mountain,” in which the men’s minimal verbal communication transmutes into a very intimate sort of carnal chemistry, is the most affecting and believable part of the movie, partly because young love is almost always touching, and partly because for these cowboys — living in a very conventional corner of the world, in a very conventional time — the stakes are particularly high. -

Sara Martín Alegre Universitat Autònoma De Barcelona

Sara Martín Alegre Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona NOTE: Paper presented at the 39th AEDEAN Conference, Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao, Spain, 11-14 November 2015 IMDB Rating (March 2015) Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (2005) 7.7 ◦ 233,193 voters Bill Condon’s Gods and Monsters (1998), 7.5 ◦ 23,613 voters The rating in the Internet Movie Database (www.imdb.com) for Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain is 7.7 (March 2015). The film that concerns me here, Bill Condon’s Gods and Monsters, does not really lag far behind, with a 7.5 rating. Considering the number of voters–233,193 for Lee’s film, but only 10% of that number (23,613 users) for Condon’s film–the [admittedly silly] question to be asked and answered is why so few spectators have been attracted by Gods and Monsters when the ratings suggest it is as good a film as Brokeback Mountain. As an admirer who has rated both films a superb 9, I wish to consider here which factors have pushed Gods and Monsters to the backward position it occupies, in terms of public and academic attention received, in comparison to the highly acclaimed Brokeback Mountain. 2 Sara Martín Alegre, “Failing to Mainstream the Gay Man: Gods and Monsters” Which factors limit the interest of audiences, reviewers and academics as regards mainstream films about gay men? AGEISM: term coined by physician and psychiatrist Robert Neil Butler “Age-ism reflects a deep seated uneasiness on the part of the young and middle- aged–a personal revulsion and distaste for growing old, disease, disability; and fear of powerlessness, ‘uselessness,’ and death” (1969: 243). -

New Queer Cinema in the USA: Rejecting

FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Trabajo de Fin de Grado New Queer Cinema in the USA: Rejecting Heteronormative Categorisations in Desert Hearts (1985) and Brokeback Mountain (2005) Autora: María Teresa Hernández Alcántara Tutora: Olga Barrios Herrero Salamanca, 2015 FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Trabajo de Fin de Grado New Queer Cinema in the USA: Rejecting Heteronormative Categorisations in Desert Hearts (1985) and Brokeback Mountain (2005) This thesis is submitted for the degree of English Studies June 2015 Tutor: Olga Barrios Herrero Vº Bº Signature ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to show my sincere and immense gratitude to my tutor, Olga Barrios, for her support, helpful advice and guidance. Her commitment, thoroughness and steady dedication helped me to increase my inspiration and write this paper with enthusiasm. In addition, I would like to thank all the teachers that have provided me with the necessary knowledge to be able to finish this degree and write this final paper. They have been a fundamental part of this process of learning and I am really thankful for their teaching and support. I would also like to thank my family for helping, encouraging and believing in me during all my academic life. Moreover, I would like to make a special mention to Cristina for her being by my side during the whole process of writing and for her unconditional support. Finally, I would like to mention my friends, whose encouragement helped me to carry out this project with motivation and illusion. -

BFI Film Quiz – August 2015

BFI Film Quiz – August 2015 General Knowledge 1 The biographical drama Straight Outta Compton, released this Friday, is an account of the rise and fall of which Los Angeles hip hop act? 2 Only two films have ever won both the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and the Academy Award for Best Picture. Name them. 3 Which director links the films Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News & As Good as it Gets, as well as TV show The Simpsons? 4 Which Woody Allen film won the 1978 BAFTA Award for Best Film, beating fellow nominees Rocky, Net- work and A Bridge Too Far? 5 The legendary Robert Altman was awarded a BFI Fellowship in 1991; but which British director of films including Reach for the Sky, Educating Rita and The Spy Who Loved Me was also honoured that year? Italian Film 1 Name the Italian director of films including 1948’s The Bicycle Thieves and 1961’s Two Women. 2 Anna Magnani became the first Italian woman to win the Best Actress Academy Award for her perfor- mance as Serafina in which 1955 Tennessee Williams adaptation? 3 Name the genre of Italian horror, popular during the 1960s and ‘70s, which includes films such as Suspiria, Black Sunday and Castle of Blood. 4 Name Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1961 debut feature film, which was based on his previous work as a novelist. 5 Who directed and starred in the 1997 Italian film Life is Beautiful, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, amongst other honours.