A Village Journey, Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section-VIII : Laboratory Services

Section‐VIII Laboratory Services 8. Laboratory Services 8.1 Haemoglobin Test ‐ State level As can be seen from the graph, hemoglobin test is being carried out at almost every FRU studied However, 10 percent medical colleges do not provide the basic Hb test. Division wise‐ As the graph shows, 96 percent of the FRUs on an average are offering this service, with as many as 13 divisions having 100 percent FRUs contacted providing basic Hb test. Hemoglobin test is not available at District Women Hospital (Mau), District Women Hospital (Budaun), CHC Partawal (Maharajganj), CHC Kasia (Kushinagar), CHC Ghatampur (Kanpur Nagar) and CHC Dewa (Barabanki). 132 8.2 CBC Test ‐ State level Complete Blood Count (CBC) test is being offered at very few FRUs. While none of the sub‐divisional hospitals are having this facility, only 25 percent of the BMCs, 42 percent of the CHCs and less than half of the DWHs contacted are offering this facility. Division wise‐ As per the graph above, only 46 percent of the 206 FRUs studied across the state are offering CBC (Complete Blood Count) test service. None of the FRUs in Jhansi division is having this service. While 29 percent of the health facilities in Moradabad division are offering this service, most others are only a shade better. Mirzapur (83%) followed by Gorakhpur (73%) are having maximum FRUs with this facility. CBC test is not available at Veerangna Jhalkaribai Mahila Hosp Lucknow (Lucknow), Sub Divisional Hospital Sikandrabad, Bullandshahar, M.K.R. HOSPITAL (Kanpur Nagar), LBS Combined Hosp (Varanasi), -

ANSWERED ON:23.02.2006 ENCROACHMENT AROUND PROTECTED MONUMENTS Nikhil Kumar Shri ;Verma Shri Ravi Prakash

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TOURISM AND CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:601 ANSWERED ON:23.02.2006 ENCROACHMENT AROUND PROTECTED MONUMENTS Nikhil Kumar Shri ;Verma Shri Ravi Prakash Will the Minister of TOURISM AND CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Union Government is aware that encroachments in and around protected monuments have been increasing day by day; (b) if so, the details thereof; (c) the details of those monuments which have come to the notice of the Union Government during each of the last three years, State/Union Territory-wise; (d) whether the Union Government is also aware that State Governments are not providing any assistance to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) for removing such encroachments; and (e) if so, the steps taken by the Union Government to remove the encroachments? Answer MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND CULTURE (SHRIMATI AMBIKA SONI) (a) to (c) There are instances of encroachments in the centrally protected monuments and a detailed list (State-wise) is at Annexure. (d) & (e) Assistance in containing and removing encroachments is sought from the respective State Government and where there are no fruitful results, actions is initiated against the encroachers by filing cases in the court of law. The Superintending Archaeologist of Circles have been vested with the powers of an Estate Officer to issue eviction notices/orders to the encroachers under Public Premises (Eviction of Unauthorised Occupants) Act, 1971. They are also authorised to issue show cause notices under the provisions of Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958 and Rules 1959 followed by an order to the District Collector/Magistrate by Director General of Archaeological Survey of India to remove such encroachment under section 19 (2) of the Act and Rules 38 (2) of the Rule. -

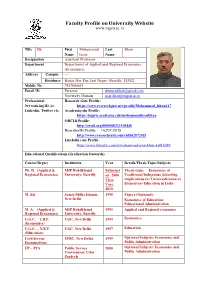

Faculty Profile on University Website

Faculty Profile on University Website www.mjpru.ac.in Title Dr. First Mohammad Last Khan Name Israr Name Designation Assistant Professor Department Department of Applied and Regional Economics (Economics) Address Campus --- Residence Kanja Das Pur, Izat Nagar, Bareilly. 243122 Mobile No. 7017004431 Email ID Personal [email protected] University Domain [email protected] Professional Research Gate Profile: Networking ID, i.e. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mohammad_Khan147 Linkedin, Twitter etc. Academia.edu Profile: https://mjpru.academia.edu/mohammadisrarkhan ORCID Profile: http://orcid.org/0000000211169448 RearcherID Profile: I-6207-2015 http://www.researcherid.com/rid/I62072015 Linekdin.com Profile: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mohammad-israr-khan-4a813b89/ Educational Qualifications (Graduation Onwards) Course/Degree Institution Year Details/Thesis Topic/Subjects Ph. D. (Applied & MJP Rohilkhand Submissi Thesis topic: Economics of Regional Economics) University, Bareilly on: 2008 Traditional Indigenous Schooling: Viva- Implications for Universalization of Voce: Elementary Education in India 2010 M. Ed. Jamia Millia Islamia, 1995 Papers (Optional): New Delhi Economics of Education; Educational Administration M. A. (Applied & MJP Rohilkhand 1993 Applied and Regional economics Regional Economics) University, Bareilly U.G.C. – J.R.F. UGC, New Delhi 1994 Economics (Economics) U.G.C. – N.E.T. UGC, New Delhi 1997 Education (Education) Civil Service UPSC, New Delhi. 1999 Optional Subjects: Economics and Examinations Public Administration UP – PCS Public Service 2000 Optional Subjects: Economics and Commission, Uttar Public Administration Pradesh Career Profile Organization / Designation Duration Nature of Duties Institution Government of Assistant 26.02.1994 1. Teaching, examination, and Delhi Primary Teacher To evaluation 25.02.1998 2. Other assigned tasks like school management, parent teacher coordination, office communication, event organization etc. -

“Everyone Has Been Silenced”; Police

EVERYONE HAS BEEN SILENCED Police Excesses Against Anti-CAA Protesters In Uttar Pradesh, And The Post-violence Reprisal Citizens Against Hate Citizens against Hate (CAH) is a Delhi-based collective of individuals and groups committed to a democratic, secular and caring India. It is an open collective, with members drawn from a wide range of backgrounds who are concerned about the growing hold of exclusionary tendencies in society, and the weakening of rule of law and justice institutions. CAH was formed in 2017, in response to the rising trend of hate mobilisation and crimes, specifically the surge in cases of lynching and vigilante violence, to document violations, provide victim support and engage with institutions for improved justice and policy reforms. From 2018, CAH has also been working with those affected by NRC process in Assam, documenting exclusions, building local networks, and providing practical help to victims in making claims to rights. Throughout, we have also worked on other forms of violations – hate speech, sexual violence and state violence, among others in Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Bihar and beyond. Our approach to addressing the justice challenge facing particularly vulnerable communities is through research, outreach and advocacy; and to provide practical help to survivors in their struggles, also nurturing them to become agents of change. This citizens’ report on police excesses against anti-CAA protesters in Uttar Pradesh is the joint effort of a team of CAH made up of human rights experts, defenders and lawyers. Members of the research, writing and advocacy team included (in alphabetical order) Abhimanyu Suresh, Adeela Firdous, Aiman Khan, Anshu Kapoor, Devika Prasad, Fawaz Shaheen, Ghazala Jamil, Mohammad Ghufran, Guneet Ahuja, Mangla Verma, Misbah Reshi, Nidhi Suresh, Parijata Banerjee, Rehan Khan, Sajjad Hassan, Salim Ansari, Sharib Ali, Sneha Chandna, Talha Rahman and Vipul Kumar. -

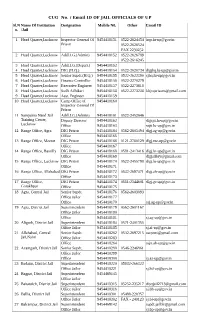

CUG No. / Email ID of JAIL OFFICIALS of up Sl.N Name of Institution Designation Mobile N0

CUG No. / Email ID OF JAIL OFFICIALS OF UP Sl.N Name Of Institution Designation Mobile N0. Other Email ID o. /Jail 1 Head Quarter,Lucknow Inspector General Of 9454418151 0522-2624454 [email protected] Prison 0522-2626524 FAX 2230252 2 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418152 0522-2626789 0522-2616245 3 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Depart.) 9454418153 4 Head Quarter,Lucknow DIG (H.Q.) 9454418154 0522-2620734 [email protected] 5 Head Quarter,Lucknow Senior Supdt.(H.Q.) 9454418155 0522-2622390 [email protected] 6 Head Quarter,Lucknow Finance Controller 9454418156 0522-2270279 7 Head Quarter,Lucknow Executive Engineer 9454418157 0522-2273618 8 Head Quarter,Lucknow Sodh Adhikari 9454418158 0522-2273238 [email protected] 9 Head Quarter,Lucknow Asst. Engineer 9454418159 10 Head Quarter,Lucknow Camp Office of 9454418160 Inspector General Of Prison 11 Sampurna Nand Jail Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418161 0522-2452646 Training Center, Deputy Director 9454418162 [email protected] Lucknow Office 9454418163 [email protected] 12 Range Office, Agra DIG Prison 9454418164 0562-2605494 [email protected] Office 9454418165 13 Range Office, Meerut DIG Prison 9454418166 0121-2760129 [email protected] Office 9454418167 14 Range Office, Bareilly DIG Prison 9454418168 0581-2413416 [email protected] Office 9454418169 [email protected] 15 Range Office, Lucknow DIG Prison 9454418170 0522-2455798 [email protected] Office 9454418171 16 Range Office, Allahabad DIG Prison 9454418172 0532-2697471 [email protected] Office 9454418173 17 Range Office, DIG Prison 9454418174 0551-2344601 [email protected] Gorakhpur Office 9454418175 18 Agra, Central Jail Senior Supdt. -

DISTRICTS COVERED 1. Mau 2. Chandauli 3. Fatehpur 4. Ghazipur

1 2ND HALF YEARLY MONITORING REPORT OF G.B. PANT SOCIAL SCIENCE INSTITUTE, ALLAHABAD ON SSA AND MDM FOR THE STATE/UT OF UTTAR PRADESH FOR THE PERIOD OF 1ST FEBRUARY, 2009 to 31 ST JULY, 2009 DISTRICTS COVERED 1. Mau 2. Chandauli 3. Fatehpur 4. Ghazipur 2 August 2009 R E P O R By S. K. Pant Submitted to Ministry of Human Resource Development, New Delhi G. B. Pant Social Science Institute Allahabad – 211 019 Phone: (0532) 2569214, 2569206, Fax: (0532) 2569207 3 Content Sl. No. Particulars Page Nos. 1. Forward 3 2. Acknowledgement 4 3. Project Team 5 4. General Information 6 - 7 5. Executive Summary of all the districts reports 8 - 24 6. Chapter - 1 Half Yearly Monitoring Report for District – 1 : Mau 25 - 55 7. Chapter - 2 Half Yearly Monitoring Report for District – 2 : Chandauli 56 - 87 8. Chapter - 3 Half Yearly Monitoring Report for District – 3 : Fatehpur 88 - 118 9. Chapter - 4 Half Yearly Monitoring Report for Distr ict – 4 : Ghazipur 119 - 150 10. List of Abbreviations 151 4 FOREWORD The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan has a set of very specific targets for implementation. During the last three to four years, there have been several interventions under this programme and the progress and problems relating to the implementation of this programme have been analyzed and reviewed periodically at regional and at the national level. On the basis of the findings of these reviews and analysis, each State/UT has been allocated with some grants and manpower to conduct the programme related activities with more vigor and enthusiasm. -

List of Indian Meteorites

290 List of Indian meteorites. (With Plate XII.) By C. A. SI~.RRAD, B.A., B.Sc. Indian Civil Service (retired). [Communicated by Dr. L. J. Spencer, F.R.S., read November 1, 1932.] N the suggestion of, and with much assistance from, Dr. L. J. Spencer, Keeper of Minerals in the British Museum,1 I have examined and, as far as possible, verified and corrected the recorded places of fall of all reported Indian meteorites. The original records were consulted, and as far as possible the places found on the large scale (usually 1 inch = 1 mile) maps in the India Office. This left a residuum regarding which inquiries were made of District Officers in India, to several of whom I am indebted for useful information which has been embodied in the list. In this list the falls are entered under their original names in alphabetical order by Provinces in British India, but in one list for all the Indian States, and the positions are indicated on the map (plate XII). The correct names of the places of fall are given in each case, in some only the spelling has required correction in accor- dance with the Government of India standard system, ~ in others the vernacular name has clearly been mistransliterated, and in many cases the name of the district or province has been changed since the fall. Wherever possible the exact date and time of fall, the latitude and longitude of the place thereof, and its distance from some big place or railway station have been given. i The large series of Indian meteorites preserved in the British Museum includes representatives of 86 of the 106 recorded falls, with many exceptional specimens; e.g. -

Resource Use Efficiency on Paddy Farms in Mau District of Eastern Uttar

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2018; 7(4): 684-687 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2018; 7(4): 684-687 Resource use efficiency on paddy farms in Mau Received: 04-05-2018 Accepted: 08-06-2018 district of eastern Uttar Pradesh Kuldeep Maurya Student, Kuldeep Maurya, Dr. RR Kushwaha, Dr. J Rai, Naveen Kumar Gautam, Department of Agricultural Ashutosh Kumar Ranjan and Arun Kumar Rajbhar Economics, Narendra Deva University of Agriculture and Technology, Kumarganj, Abstract Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh, India The present study aims to analyze the resource use efficiency, marginal value productivity of variable resources, constraint and suggestion in paddy production entitled “Economics of paddy production and Dr. RR Kushwaha its processing in district Mau of Eastern Uttar Pradesh”. The data pertained to agriculture year 2015- Asstt. Professor, 2016. The study was conducted in five villages of Ghosi block in Mau district taking a random sample of Department of Agricultural 100 farmers. The primary data were collected by survey method through personal interview by pretested Economics, Narendra Deva structured interview schedule. The Cobb-Douglas production function was applied to measure the University of Agriculture and efficiency of various resources used in the production of paddy. To find out the resources use efficiency Technology, Kumarganj, of five variables namely, seed, fertilizer, irrigation, tractor and human labour was considered. Return to Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh, India scale in respect to various resources on marginal, small and medium farms were found 0.862059, Dr. J Rai 0.949245, and 0.906866 respectively. The cultivation of paddy was characterized by decreasing returns Asstt. -

1 Village Kathera, Block Akrabad, Sasni to Nanau Road , Tehsil Koil

Format for Advertisement in Website Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Uttar Pradesh, as per following details: Fixed Fee / Security Estimated monthly Type of Minimum Dimension (in M.)/Area of Mode of Minimum Bid Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Category Finance to be arranged by the applicant Deposit (Rs. Sales Potential # Site* the site (in Sq. M.). * Selection amount (Rs. In In Lakhs) Lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 SC, SC CC-1, SC PH ST, ST CC-1, ST PH OBC, OBC CC- CC / DC / Estimated fund Estimated working Draw of Regular / 1, OBC PH CFS required for MS+HSD in Kls Frontage Depth Area capital requirement Lots / Rural development of for operation of RO Bidding infrastructure at RO OPEN, OPEN CC- 1, OPEN CC- 2,OPEN-PH Village Kathera, Block Akrabad, Sasni to Nanau Road , Draw of 1 Tehsil Koil, Dist Aligarh ALIGARH RURAL 90 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Dhansia, Block Jewar, Tehsil Jewar,On Jewar to GAUTAM BUDH Draw of 2 Khurja Road, dist GB Nagar NAGAR RURAL 160 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Dewarpur Pargana & Distt. Auraiya Bidhuna Auraiya Draw of 3 Road Block BHAGYANAGAR AURAIYA RURAL 150 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Kudarkot on Kudarkot Ruruganj Road, Block Draw of 4 AIRWAKATRA AURAIYA RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 5 Village Behta Block Saurikh on Saurikh to Vishun Garh Road KANNAUJ RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 6 Village Nadau, -

High Court of Judicature at Allahabad

URL: http://www.liiofindia.org/in/cases/up/INUPHC/2007/14725.html High Court of Judicature at Allahabad Shyammal Ranjan Mukerjee v. Nirmal Ranjan Mukerjee And Others - WRIT - C No. - 56447 of 2003 [2007] INUPHC 14725 (30 August 2007) This is an UNCERTIFIED copy for information/reference. For authentic copy please refer to certified copy only. In case of any mistake, please bring it to the notice of Joint Registrar(Copying). HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT ALLAHABAD Reserved Civil Misc. Writ Petition No. 56447 of 2003 Shyamal Ranjan Mukherjee............................Petitioner Vs. Nirmal Ranjan Mukherjee & Others......................Respondents Hon'ble S.N. Srivastava, J. After hearing learned counsel for the parties, learned Amicus Curaei and Sri I.N. Singh, learned counsel appearing for Kashi Vidhwat Parishad, following questions arises to be decided in the present Case. (i) If Deed of Dedication to Deity for religious purposes prohibits any alienation by way of sale or mortgage whether the Shebait could alienate the property vested in Deity? (ii) Whether the Temple which is abode of the Deity is alienable even if there is no such prohibition in the Deed of Dedication? (iii) Whether the properties other than Temple vested in the Deity are alienable? (iv) Whether considering the historical background of attacks on Temples and Religious Institutions of Hindus for about more than 1200 years, whether the Temples and Religious Institutions require any protection from the State, if so, who are Hindus and whether Hinduism is religion or Dharm and are entitled to get protection under Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution of India and if so what protection is required to safeguard Hindu Temples and Religious Institutions? (v) As the matter relates to Temple of Lord Krishna who has given Bhagvad Geeta to the man kind, whether Bhagvad Geeta propounds any thought or belief or Dharm common to all faiths, beliefs, way of worship (all religions born in India and part of Hinduism)? Facts of the case are as follows:- Premises No. -

Basic Information of Urban Local Bodies – Uttar Pradesh

BASIC INFORMATION OF URBAN LOCAL BODIES – UTTAR PRADESH As per 2006 As per 2001 Census Election Name of S. Growth Municipality/ Area No. of No. Class House- Total Rate Sex No. of Corporation (Sq. Male Female SC ST (SC+ ST) Women Rate Rate hold Population (1991- Ratio Wards km.) Density Membe rs 2001) Literacy 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 I Saharanpur Division 1 Saharanpur District 1 Saharanpur (NPP) I 25.75 76430 455754 241508 214246 39491 13 39504 21.55 176 99 887 72.31 55 20 2 Deoband (NPP) II 7.90 12174 81641 45511 36130 3515 - 3515 23.31 10334 794 65.20 25 10 3 Gangoh (NPP) II 6.00 7149 53913 29785 24128 3157 - 3157 30.86 8986 810 47.47 25 9 4 Nakur (NPP) III 17.98 3084 20715 10865 9850 2866 - 2866 36.44 1152 907 64.89 25 9 5 Sarsawan (NPP) IV 19.04 2772 16801 9016 7785 2854 26 2880 35.67 882 863 74.91 25 10 6 Rampur Maniharan (NP) III 1.52 3444 24844 13258 11586 5280 - 5280 17.28 16563 874 63.49 15 5 7 Ambehta (NP) IV 1.00 1739 13130 6920 6210 1377 - 1377 27.51 13130 897 51.11 12 4 8 Titron (NP) IV 0.98 1392 10501 5618 4883 2202 - 2202 30.53 10715 869 54.55 11 4 9 Nanauta (NP) IV 4.00 2503 16972 8970 8002 965 - 965 30.62 4243 892 60.68 13 5 10 Behat (NP) IV 1.56 2425 17162 9190 7972 1656 - 1656 17.80 11001 867 60.51 13 5 11 Chilkana Sultanpur (NP) IV 0.37 2380 16115 8615 7500 2237 - 2237 27.42 43554 871 51.74 13 5 86.1 115492 727548 389256 338292 65600 39 65639 23.38 8451 869 67.69 232 28 2 Muzaffarnagar District 12 Muzaffarnagar (NPP) I 12.05 50133 316729 167397 149332 22217 41 22258 27.19 2533 892 72.29 45 16 13 Shamli -

World Bank Document

Govermnment f Utar Pradesh ENVIRONMENTAL Public Works DepartmentEN IO M TA Lucknowjndla ASSESSMENT (PHASE- 11) Public Disclosure Authorized December 2003 E505 Volume 9 PL ' c Co-ordnatlngConsltant (PCC)Swvices t~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~La lb, 4114- 1N) seiAies for Wbtr Pradesh Public Disclosure Authorized Consulftncy SStt Rods ProJect Public Disclosure Authorized DHV CONSULTANTS BV Public Disclosure Authorized in associabon with Halcrow and Partners Funding Agency: Operation Research Group Development Consultants Ltd. THE WORLD BANK MDP Consultants ( Pvt) Ltd r s Environment Assessment (Phase 11) DHV Consultants BV December 2003 Project Co-ordinating Consultants Services for the Uttar Pradesh State Roads Project, under IBRD Loan No. 4114-IN ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (PHASE II) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 THE UTrAR PRADESH STATE ROADS 11 environment parameters, seven routes were PROJECT prioritised for taking up for subsequent detailed design work in the second phase as under: The Uttar Pradesh State Roads Project is financed Route 3 Pilibhit-Khutar: .................. 72.806 km under the World Bank loan number 4114-IN. The Route 4B Lucknow-Bangarmau: ........ 73.229 km Uttar Pradesh Public Works Department, as the Route 6 Sitapur-Bahraich: ............... 88.336 km executing agency, represented the Government Route 7B Azamgarh-Phephana ....... 100.929 km of India in terms of liaison and co-ordination with Route 1OA Gorakhpur-Shahganj: ...... 109.656 km the World Bank. The Project is performed by a Route 11 Moradabad-Bazpur: .......... 36.335 km consortium of consultants consisting of Route 16 Deoria-Ballia: .................. 109.447 km DHV Consultants BV as lead consultant, Halcrow and Partners, Operations Research Group, Total Phase II ................ ....... 590.74 km Development Consultants Ltd., and MDP Consultants Pvt.