List of Projects in South Africa 2004 – 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

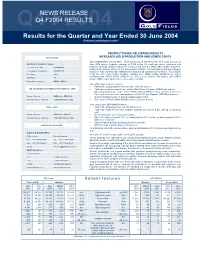

Q4 F2004 F2004 RESULTS Results for the Quarter and Year Ended 30 June 2004 -Reviewed Preliminary Results

NEWS RELEASE Q4Q4 F2004 F2004 RESULTS Results for the Quarter and Year Ended 30 June 2004 -Reviewed preliminary results- RESTRUCTURING DELIVERING RESULTS INCREASED GOLD PRODUCTION AND LOWER COSTS STOCK DATA JOHANNESBURG. 29 July 2004 – Gold Fields Limited (NYSE & JSE: GFI) today announced Number of shares in issue June 2004 quarter headline earnings of R129 million (26 cents per share) compared with - at end June 2004 491,480,690 headline earnings of R221 million (45 cents per share) in the March 2004 quarter and R494 million (104 cents per share) for the June quarter of 2003. The reduction in earnings is largely - average for the quarter 491,431,716 gold price and exchange rate related and masks a solid operating performance. In US dollar Free Float 100% terms the June 2004 quarter headline earnings were US$20 million (US$0.04 per share) compared with US$32 million (US$0.07 per share) in the March 2004 quarter and US$64 ADR Ratio 1:1 million (US$0.14 per share) for the June quarter of 2003. Bloomberg / Reuters GFISJ / GFLJ.J June 2004 quarter salient features: • Attributable gold production increased to 1,042,000 ounces; JSE SECURITIES EXCHANGE SOUTH AFRICA – (GFI) • Total cash costs decreased 2 per cent to R66,218 per kilogram (US$312 per ounce); • Operating profit down 17 per cent to R545 million (US$83 million), exclusively due to a 6 per cent reduction in the rand gold price to R83,731 per kilogram (US$395 per ounce); Range - Quarter ZAR85.00 – ZAR65.02 • Organic growth projects on track in Australia and Ghana; Average Volume - Quarter 1,398,900 shares / day • Write-down of R426 million (US$62 million) at Beatrix 4 shaft. -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA Regulation Gazette No. 10177 Regulasiekoerant February Vol. 668 11 2021 No. 44146 Februarie ISSN 1682-5845 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 44146 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 44146 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 FEBRUARY 2021 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Contents Gazette Page No. No. No. GOVERNMENT NOTICES • GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS Transport, Department of / Vervoer, Departement van 82 South African National Roads Agency Limited and National Roads Act (7/1998): Huguenot, Vaal River, Great North, Tsitsikamma, South Coast, North Coast, Mariannhill, Magalies, N17 and R30/R730/R34 Toll Roads: Publication of the amounts of Toll for the different categories of motor vehicles, and the date and time from which the toll tariffs shall become payable .............................................................................................................................................. 44146 3 82 Suid-Afrikaanse Nasionale Padagentskap Beperk en Nasionale Paaie Wet (7/1998) : Hugenote, Vaalrivier, Verre Noord, Tsitsikamma, Suidkus, Noordkus, Mariannhill, Magalies, N17 en R30/R730/R34 Tolpaaie: Publisering -

Direction on Measures to Address, Prevent and Combat the Spread of COVID-19 in the Air Services for Adjusted Alert Level 3

Laws.Africa Legislation Commons South Africa Disaster Management Act, 2002 Direction on Measures to Address, Prevent and Combat the Spread of COVID-19 in the Air Services for Adjusted Alert Level 3 Legislation as at 2021-01-29. FRBR URI: /akn/za/act/gn/2021/63/eng@2021-01-29 PDF created on 2021-10-02 at 16:36. There may have been updates since this file was created. Check for updates About this collection The legislation in this collection has been reproduced as it was originally printed in the Government Gazette, with improved formatting and with minor typographical errors corrected. All amendments have been applied directly to the text and annotated. A scan of the original gazette of each piece of legislation (including amendments) is available for reference. This is a free download from the Laws.Africa Legislation Commons, a collection of African legislation that is digitised by Laws.Africa and made available for free. www.laws.africa [email protected] There is no copyright on the legislative content of this document. This PDF copy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (CC BY 4.0). Share widely and freely. Table of Contents South Africa Table of Contents Direction on Measures to Address, Prevent and Combat the Spread of COVID-19 in the Air Services for Adjusted Alert Level 3 3 Government Notice 63 of 2021 3 1. Definitions 3 2. Authority of directions 4 3. Purpose of directions 4 4. Application of directions 4 5. Provision of access to hygiene and disinfection control at airports designated as Ports of Entry 4 6. -

Huguenot, Vaal River, Great North

STAATSKOERANT, 9 MAART 2012 No.35052 27 No. 128 9 March 2012 THE SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL ROADS AGENCY SOC LIMITED HUGUENOT, VAAL RIVER, GREAT NORTH, TSITSIKAMMA, SOUTH COAST, NORTH COAST, MARIANNHILL, MAGALIES, N17 AND R30/R730/R34 TOLL ROADS: PUBLICATION OF THE AMOUNTS OF TOLL FOR THE DIFFERENT CATEGORIES OF MOTOR VEHICLES, AND THE DATE AND TIME FROM WHICH THE TOLL TARIFFS SHALL BECOME PAYABLE The Head of the Department hereby, in terms of section 28(4) read with section 27(3) of The South African National Roads Agency Limited and National Roads Act, 1998 (Act No. 7 of 1998) [the Act], makes known that the amounts oftoll to be levied in terms of section 27{1)(b) of the Act at the toll plazas located on the Huguenot. Vaal River, Great North, Tsitsikamma, South Coast, North Coast, Mariannhill, Magalies, N17 and R30/R730/R34 Toll Roads, and the date and time from which the amounts of toll shall become payable, have been determined by the Minister of Transport in terms of section 27(3)(a) of the Act, and that the said amounts shall be levied in terms of section 27(3)(b) and (d) of the Act, as set out in the Schedule . .. 28 No.35052 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 9 MARCH 2012 SCHEDULE 1. DEFINITIONS The following words and expressions shall have the meanings stated, unless the context otherwise indicates. 1.1 "Abnonnal vehicle" means a motor vehicle exceeding the legal dimensions as described in the Road Traffic Act, 1996 (Act No. 93 of 1996), as amended, or in any other law. -

Chanticleer Holdings to Open Third South Africa Hooters Restaurant in Johannesburg

October 30, 2014 Chanticleer Holdings to Open Third South Africa Hooters Restaurant in Johannesburg CHARLOTTE, NC -- (Marketwired) -- 10/30/14 -- Chanticleer Holdings, Inc.( NASDAQ: HOTR) (Chanticleer Holdings, or the "Company"), owner and operator of multiple restaurant brand internationally and domestically, today announced that the Company will be opening a new South Africa Hooters location in Ruimsig, a suburb of Johannesburg. It is Chanticleer's third location in the Johannesburg area and fourth in the province of Gauteng, situated on Hendrik Potgieter Road, famously known as the longest road in the city. With over 260,000 people and a median age of 31 living within a 5 mile radius to the restaurant, the Company believes the location will generate significantly higher revenues than at its prior CapeTown location. The 5,900square foot restaurant will seat 220 and house 25 flat screen TV's, a great venue for the local patrons to enjoy their favorite sporting events. The VIP opening is on December 11, 2014 and will open to the public on the December 13, 2014. Ruimsig Stadium, a multi-sport events complex including track, cycling and soccer ("football"), is nearby. Various teams trained and practiced at the stadium for the 2010 FIFA World Cup and it will be hosting the Paintball Super Cup 2014 this December 11-14th. Darren Smith, CFO of Hooters South Africa, commented, "There's great potential to drive significant revenues to this location as the Hooters brand now has a strong foothold in the Johannesburg area. We look forward to expanding the brand in one of our country's exceptional growing cities." Mike Pruitt, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, commented, "We believe relocating our CapeTown location to Ruimsig was the right strategic move at this time to increase our revenue and profitability in the South Africa market. -

International Air Services (COVID-19 Restrictions on the Movement of Air Travel) Directions, 2020

Laws.Africa Legislation Commons South Africa Disaster Management Act, 2002 International Air Services (COVID-19 Restrictions on the movement of air travel) Directions, 2020 Legislation as at 2020-12-03. FRBR URI: /akn/za/act/gn/2020/415/eng@2020-12-03 PDF created on 2021-09-26 at 02:36. There may have been updates since this file was created. Check for updates About this collection The legislation in this collection has been reproduced as it was originally printed in the Government Gazette, with improved formatting and with minor typographical errors corrected. All amendments have been applied directly to the text and annotated. A scan of the original gazette of each piece of legislation (including amendments) is available for reference. This is a free download from the Laws.Africa Legislation Commons, a collection of African legislation that is digitised by Laws.Africa and made available for free. www.laws.africa [email protected] There is no copyright on the legislative content of this document. This PDF copy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (CC BY 4.0). Share widely and freely. Table of Contents South Africa Table of Contents International Air Services (COVID-19 Restrictions on the movement of air travel) Directions, 2020 3 Government Notice 415 of 2020 3 1. Definitions 3 2. Authority 4 3. Purpose of directions 4 4. Application of the directions 4 5. International flights and domestic flights 4 5A. Airport and airlines 7 5B. General aviation 7 5C. *** 8 5D. Compliance with the measures for the prevention of the spread of COVID-19 8 6. -

Explore the Northern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Northern Cape Province When Schalk van Niekerk traded all his possessions for an 83.5 carat stone owned by the Griqua Shepard, Zwartboy, Sir Richard Southey, Colonial Secretary of the Cape, declared with some justification: “This is the rock on which the future of South Africa will be built.” For us, The Star of South Africa, as the gem became known, shines not in the East, but in the Northern Cape. (Tourism Blueprint, 2006) 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Namaqualand Component # 1 - Namaqualand Component # 2 - The Hantam Karoo Component # 3 - Towns along the N14 Component # 4 - Richtersveld Component # 5 - The West Coast Module # 5 - Karoo Region Component # 1 - Introduction to the Karoo and N12 towns Component # 2 - Towns along the N1, N9 and N10 Component # 3 - Other Karoo towns Module # 6 - Diamond Region Component # 1 - Kimberley Component # 2 - Battlefields and towns along the N12 Module # 7 - The Green Kalahari Component # 1 – The Green Kalahari Module # 8 - The Kalahari Component # 1 - Kuruman and towns along the N14 South and R31 Northern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus. It may not be copied, distributed or reproduced in any format whatsoever without the express written permission of WildlifeCampus. 3 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module 1 - Component 1 Northern Cape Province Overview Introduction Diamonds certainly put the Northern Cape on the map, but it has far more to offer than these shiny stones. -

Graaff-Reinet: Urban Design Plan August 2012 Contact Person

Graaff-Reinet: Urban Design Plan August 2012 Contact Person: Hedwig Crooijmans-Allers The Matrix cc...Urban Designers and Architects 22 Lansdowne Place Richmond Hill Port Elizabeth Tel: 041 582 1073 email: [email protected] GRAAFF -REINET: URBAN DESIGN PLAN Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1. General .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Stakeholder and Public Participation Process ................................................................................................... 6 A: Traffic Study 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 8 2.1. Background ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.2. Methodology ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Study Area ........................................................................................................................................................ -

No. DATE HOST VERSUS STADIUM PROVINCE 1. 1994.04.24 South

No. DATE HOST VERSUS STADIUM PROVINCE 1. 1994.04.24 South Africa Zimbabwe Mmabatho Stadium North West 2. 1994.05.10 South Africa Zambia Ellis Park Gauteng 3. 1994.11.26 South Africa Ghana Loftus Versfeld Gauteng 4. 1994.11.30 South Africa Cote d'Ivoire Boet Erasmus Stadium Eastern Cape 5. 1994.12.03 South Africa Cameroon Ellis Park Gauteng 6. 1995.05.13 South Africa Argentina Ellis Park Gauteng 7. 1995.09.30 South Africa Mozambique Soccer City Gauteng 8. 1995.11.22 South Africa Zambia Loftus Versfeld Gauteng 9. 1995.11.26 South Africa Zimbabwe Soccer City Gauteng 10. 1995.11.24 South Africa Egypt Mmabatho Stadium North West 11. 1995.12.15 South Africa Germany Johannesburg Athletics Stadium Gauteng 12. 1996.01.13 South Africa Cameroon Soccer City Gauteng 13. 1996.01.20 South Africa Angola Soccer City Gauteng 14. 1996.01.24 South Africa Egypt Soccer City Gauteng 15. 1996.01.27 South Africa Algeria Soccer City Gauteng 16. 1996.01.31 South Africa Ghana Soccer City Gauteng 17. 1996.02.03 South Africa Tunisia Soccer City Gauteng 18. 1996.04.24 South Africa Brazil Soccer City Gauteng 19. 1996.06.15 South Africa Malawi Soccer City Gauteng 20. 1996.09.14 South Africa Kenya King's Park KwaZulu-Natal 21. 1996.09.18 South Africa Australia Johannesburg Athletics Stadium Gauteng 22. 1996.09.21 South Africa Ghana Loftus Versfeld Gauteng 23. 1996.11.09 South Africa Zaire Soccer City Gauteng 24. 1997.06.04 South Africa Netherlands Soccer City Gauteng 25. 1997.06.08 South Africa Zambia Soccer City Gauteng 26. -

The South African Qualifications Authority

THE SOUTH AFRICAN QUALIFICATIONS AUTHORITY Articulation Between Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Colleges and Higher Education Institutions (HEIs): National Articulation Baseline Study Report October 2017 ARTICULATION BETWEEN TECHNICAL AND VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING (TVET) COLLEGES AND HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS (HEIs) NATIONAL ARTICULATION BASELINE STUDY REPORT October 2017 DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) and only those parts of the text clearly flagged as decisions or summaries of decisions taken by the Authority should be seen as reflecting SAQA policy and/or views. COPYRIGHT All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The National Articulation Baseline Study reported here forms part of SAQA’s long-term partnership research with the Durban University of Technology (DUT) “Developing an understanding of the enablers of student transitioning between Technical and Vocation Education and Training (TVET) Colleges and HEIs and beyond”. Data were gathered, and initial analyses done, for the National Articulation Baseline Study, by Dr Heidi Bolton, Dr Eva Sujee, Ms Renay Pillay, and Ms Tshidi Leso (all of SAQA). The in-depth analyses were conducted by -

Albert Luthuli Local Municipality 2013/14

IDP REVIEW 2013/14 IIntegrated DDevelopment PPlan REVIEW - 2013/14 “The transparent, innovative and developmental local municipality that improves the quality of life of its people” Published by Chief Albert Luthuli Local Municipality Email: [email protected] Phone: (017) 843 4000 Website: www.albertluthuli.gov.za IDP REVIEW 2013/14 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms 6 A From the desk of the Executive Mayor 7 B From the desk of the Municipal Manager 9 PART 1- INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1 INTRODUCTION 11 1.2 STATUS OF THE IDP 11 1.2.1 IDP Process 1.2.1.1 IDP Process Plan 1.2.1.2 Strategic Planning Session 1.3 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 12 1.4 INTER GOVERNMENTAL PLANNING 13 1.4.1 List of Policies 14 1.4.2 Mechanisms for National planning cycle 15 1.4.3 Outcomes Based Approach to Delivery 16 1.4.4 Sectoral Strategic Direction 16 1.4.4.1 Policies and legislation relevant to CALM 17 1.4.5 Provincial Growth and Development Strategy 19 1.4.6 Municipal Development Programme 19 1.5 CONCLUSION 19 PART 2- SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 2.1 BASIC STATISTICS AND SERVICE BACKLOGS 21 2.2 REGIONAL CONTEXT 22 2.3 LOCALITY 22 2.3.1 List of wards within municipality with area names and coordinates 23 2.4 POPULATION TRENDS AND DISTRIBUTION 25 2.5 SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT 29 2.5.1 Land Use 29 2.5.2 Spatial Development Framework and Land Use Management System 29 Map: 4E: Settlement Distribution 31 Map 8: Spatial Development 32 2.5.3 Housing 33 2.5.3.1 Household Statistics 33 2.5.4 Type of dwelling per ward 34 2.5.5 Demographic Profile 34 2.6 EMPLOYMENT TRENDS 39 2.7 INSTITUTIONAL -

RUGBY LIST 42: February 2019

56 Surrey Street Harfield Village 7708 Cape Town South Africa www.selectbooks.co.za Telephone: 021 424 6955 Email: [email protected] Prices include VAT. Foreign customers are advised that VAT will be deducted from their purchases. We prefer payment by EFT - but Visa, Mastercard, Amex and Diners credit cards are accepted. Approximate Exchange Rates £1 = R17.50 Aus$1 = R9.70 NZ$1 = R9.20 €1 = R15.30 Turkish Lira1 = R2.60 US$1= R13.40 RUGBY LIST 42: February 2019 PROGRAMMES PROGRAMMES..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Argentina............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Australia.............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Canada.................................................................................................................................................................5 England ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 Fiji....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 France.................................................................................................................................................................