Third Culture Kids’ Relate to and Live in the City Around Them? an Ethnographic Study of Urban Practices and Preferences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living in Spain Your Essential Emigration Guide Living in Spain Your Essential Emigration Guide

LIVING IN SPAIN YOUR ESSENTIAL EMIGRATION GUIDE LIVING IN SPAIN YOUR ESSENTIAL EMIGRATION GUIDE Contents INTRODUCTION p3 About this guide CHAPTER 1 p5 Why Spain? CHAPTER 2 p13 Where to live in Spain CHAPTER 3 p58 Finding Work CHAPTER 4 p66 Visas, Permits and other red tape CHAPTER 5 p75 Retiring to Spain CHAPTER 6 p89 Health CHAPTER 7 p101 Schools & Colleges CHAPTER 8 p116 Finances CHAPTER 9 p126 Culture Living In Spain © Copyright: Telegraph Media Group LIVING IN SPAIN YOUR ESSENTIAL EMIGRATION GUIDE SUN, SEA AND SALVADOR: Spain is home to many delightful towns, such as Cadaqués, Dali’s home town and inspiration The Telegraph’s Living In Spain guide has been compiled using a variety of source material. Some has come from our correspondents who are lucky enough to be paid by us to live there, or other journalists who have made occasional visits, to write travel features or to cover news or sporting events. Other information has come from official sources. By far the most useful info on life in Spain in this guide, however, has come from many ordinary people – ordinary Spaniards willing to share insights into their country and ordinary Britons, many of them Telegraph readers, who have already made the move you are contemplating, and are now residents in Spain. They have discovered what worked and what didn’t, and gone through the highs and lows that accompany any Expat journey. It is their experiences that I believe will be most valuable for you as you make your plans to follow them. Our intention is to provide you with the most comprehensive, up-to-date guide to your destination, with everything you need in one place, in an easy-to-use format. -

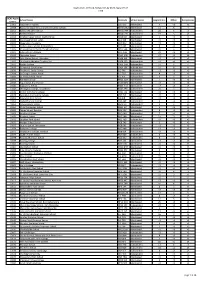

2014 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained -

20Th November 2015 Dear Request for Information Under the Freedom

Governance & Legal Room 2.33 Services Franklin Wilkins Building 150 Stamford Street Information Management London and Compliance SE1 9NH Tel: 020 7848 7816 Email: [email protected] By email only to: 20th November 2015 Dear Request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (“the Act”) Further to your recent request for information held by King’s College London, I am writing to confirm that the requested information is held by the university. Some of the requested is being withheld in accordance with section 40 of the Act – Personal Information. Your request We received your information request on 26th October 2015 and have treated it as a request for information made under section 1(1) of the Act. You requested the following information. “Would it be possible for you provide me with a list of the schools that the 2015 intake of first year undergraduate students attended directly before joining the Kings College London? Ideally I would like this information as a csv, .xls or similar file. The information I require is: Column 1) the name of the school (plus any code that you use as a unique identifier) Column 2) the country where the school is located (ideally using the ISO 3166-1 country code) Column 3) the post code of the school (to help distinguish schools with similar names) Column 4) the total number of new students that joined Kings College in 2015 from the school. Please note: I only want the name of the school. This request for information does not include any data covered by the Data Protection Act 1998.” Our response Please see the attached spreadsheet which contains the information you have requested. -

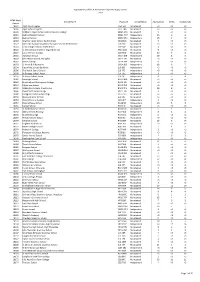

2013 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2013 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 15 6 4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy (formerly Upper School) Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 9 <3 <3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 5 4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 18 6 6 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 8 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 18 9 7 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 9 5 4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained <3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 8 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon -

Entidades Con Convenio De Colaboración Con La Uned

Vicerrectorado de Estudiantes y Emprendimiento Servicio de Acceso a la Universidad UNED-Application Service for International Students in Spain ENTIDADES CON CONVENIO DE COLABORACIÓN CON LA UNED PARA LA GESTIÓN DEL ACCESO Y ADMISIÓN DE ESTUDIANTES DE SISTEMAS EDUCATIVOS INTERNACIONALES, A LAS UNIVERSIDADES ESPAÑOLAS SISTEMA EDUCATIVO ENTIDADES CON CONVENIO MARCO FRANCÉS SERVICIO CULTURAL DE LA EMBAJADA DE FRANCIA EN ESPAÑA IBO BACHILLERATO INTERNACIONAL ORGANIZACIÓN DE BACHILLERATO INTERNACIONAL ACBIE BACHILLERATO INTERNACIONAL ASOCIACIÓN DE CENTROS DE BACHILLERATO INTERNACIONAL EN ESPAÑA NABSS BRITÁNICO ASOCIACIÓN DE COLEGIOS BRITÁNICOS EN ESPAÑA UNIVERSIDADES ENTIDADES CON ACUERDO BILATERAL CHINO UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA LA MANCHA - PROGRAMA DE ESPAÑOL EN TOLEDO VARIOS SISTEMAS CEDEU - CENTRO ADSCRITO A LA UNIVERSIDAD REY JUAN CARLOS VARIOS SISTEMAS EUSES - ESCOLA UNIVERSITARIA DE LA SALUT I L’ESPORT VARIOS SISTEMAS ESNE - E. U. DE DISEÑO, INNOVACIÓN Y TECNOLOGÍA VARIOS SISTEMAS FUNDACIÓN UNIVERSITARIA DEL BAGES VARIOS SISTEMAS IE UNIVERSIDAD VARIOS SISTEMAS LA SALLE CENTRO UNIVERSITARIO VARIOS SISTEMAS UNIVERSIDAD ALFONSO X EL SABIO VARIOS SISTEMAS UNIVERSIDAD CAMILO JOSÉ CELA VARIOS SISTEMAS UNIVERSIDAD CEU SAN PABLO - MADRID VARIOS SISTEMAS UNIVERSIDAD LOYOLA ANDALUCÍA VARIOS SISTEMAS UNIVERSIDAD NEBRIJA VARIOS SISTEMAS UNIVERSITAT DE VIC - UNIVERSITAT CENTRAL DE CATALUNYA SISTEMA EDUCATIVO ENTIDADES CON ACUERDO BILATERAL ALEMÁN COLEGIO ALEMÁN DE BARCELONA ALEMÁN COLEGIO ALEMÁN DE BILBAO ALEMÁN COLEGIO ALEMÁN DE LAS PALMAS ALEMÁN -

Institution Code Institution Title a and a Co, Nepal

Institution code Institution title 49957 A and A Co, Nepal 37428 A C E R, Manchester 48313 A C Wales Athens, Greece 12126 A M R T C ‐ Vi Form, London Se5 75186 A P V Baker, Peterborough 16538 A School Without Walls, Kensington 75106 A T S Community Employment, Kent 68404 A2z Management Ltd, Salford 48524 Aalborg University 45313 Aalen University of Applied Science 48604 Aalesund College, Norway 15144 Abacus College, Oxford 16106 Abacus Tutors, Brent 89618 Abbey C B S, Eire 14099 Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar Sc 16664 Abbey College, Cambridge 11214 Abbey College, Cambridgeshire 16307 Abbey College, Manchester 11733 Abbey College, Westminster 15779 Abbey College, Worcestershire 89420 Abbey Community College, Eire 89146 Abbey Community College, Ferrybank 89213 Abbey Community College, Rep 10291 Abbey Gate College, Cheshire 13487 Abbey Grange C of E High School Hum 13324 Abbey High School, Worcestershire 16288 Abbey School, Kent 10062 Abbey School, Reading 16425 Abbey Tutorial College, Birmingham 89357 Abbey Vocational School, Eire 12017 Abbey Wood School, Greenwich 13586 Abbeydale Grange School 16540 Abbeyfield School, Chippenham 26348 Abbeylands School, Surrey 12674 Abbot Beyne School, Burton 12694 Abbots Bromley School For Girls, St 25961 Abbot's Hill School, Hertfordshire 12243 Abbotsfield & Swakeleys Sixth Form, 12280 Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge 12732 Abbotsholme School, Staffordshire 10690 Abbs Cross School, Essex 89864 Abc Tuition Centre, Eire 37183 Abercynon Community Educ Centre, Wa 11716 Aberdare Boys School, Rhondda Cynon 10756 Aberdare College of Fe, Rhondda Cyn 10757 Aberdare Girls Comp School, Rhondda 79089 Aberdare Opportunity Shop, Wales 13655 Aberdeen College, Aberdeen 13656 Aberdeen Grammar School, Aberdeen Institution code Institution title 16291 Aberdeen Technical College, Aberdee 79931 Aberdeen Training Centre, Scotland 36576 Abergavenny Careers 26444 Abersychan Comprehensive School, To 26447 Abertillery Comprehensive School, B 95244 Aberystwyth Coll of F. -

Living in Spain Your Essential Emigration Guide Living in Spain Your Essential Emigration Guide

LIVING IN SPAIN YOUR ESSENTIAL EMIGRATION GUIDE LIVING IN SPAIN YOUR ESSENTIAL EMIGRATION GUIDE Contents INTRODUCTION p3 About this guide CHAPTER 1 p5 Why France? CHAPTER 2 p13 Where to live in France CHAPTER 3 p58 Finding Work CHAPTER 4 p66 Visas, Permits and other red tape CHAPTER 5 p75 Retiring to France CHAPTER 6 p89 Health CHAPTER 7 p116 Schools & Colleges CHAPTER 8 p126 Finances CHAPTER 9 p123 Culture Living In Spain © Copyright: Telegraph Media Group LIVING IN SPAIN YOUR ESSENTIAL EMIGRATION GUIDE SUN, SEA AND SALVADOR: Spain is home to many delightful towns, such as Cadaqués, Dali’s home town and inspiration The Telegraph’s Living In Spain guide has been compiled using a variety of source material. Some has come from our correspondents who are lucky enough to be paid by us to live there, or other journalists who have made occasional visits, to write travel features or to cover news or sporting events. Other information has come from official sources. By far the most useful info on life in Spain in this guide, however, has come from many ordinary people – ordinary Spaniards willing to share insights into their country and ordinary Britons, many of them Telegraph readers, who have already made the move you are contemplating, and are now residents in Spain. They have discovered what worked and what didn’t, and gone through the highs and lows that accompany any Expat journey. It is their experiences that I believe will be most valuable for you as you make your plans to follow them. Our intention is to provide you with the most comprehensive, up-to-date guide to your destination, with everything you need in one place, in an easy-to-use format. -

Revisión Enero 2009

REVISIÓN ENERO 2009 1 Vivir en Madrid. Guía del expatriado Índice............................................................................................................................1 Presentación................................................................................................................3 1. Introducción.............................................................................................................5 España: gobierno local, regional y nacional Madrid capital de España Símbolos de Madrid Organización territorial La actividad económica de Madrid Clima Diferencia horaria 2. Instalarse en Madrid…………………………………………………………………....12 Entrada en España, estancia y residencia: requisitos legales Empadronarse en Madrid 3. Vivir en Madrid.......................................................................................................22 Alojamiento temporal Zonas residenciales Alquiler de vivienda Compra de vivienda Alta o cambio de nombre en los suministros: agua, luz, gas, teléfono 4. Sistema bancario y fiscalidad..............................................................................32 Bancos y cajas de ahorros Fiscalidad 5. Comunicaciones....................................................................................................39 Telefónicas Medios de comunicación Correos 6. Transporte.............................................................................................................44 El Aeropuerto Madrid-barajas Accesos por carretera Viajar en tren Transporte metropolitano: metro, -

Estudios Sectoriales DBK

Estudios Sectoriales DBK Estudio del sector Colegios Privados Objeto del estudio El estudio ofrece el análisis de la estructura de la oferta, la evolución reciente, las previsiones y la situación económico-financiera del sector, así como el posicionamiento y los resultados de 41 de las principales empresas/grupos que operan en el mismo. El informe se acompaña de un archivo Excel, el cual contiene los estados financieros individuales de las 40 mayores sociedades gestoras de colegios integrantes de las empresas/grupos analizados, el agregado de dichos estados financieros, los principales ratios económico-financieros individuales y agregados, y una serie de tablas comparativas de los resultados y ratios de las sociedades. Principales contenidos: Evolución del número de colegios (públicos, privados concertados, privados no concertados) y su distribución por tipo de enseñanza y por zonas geográficas Evolución del número de alumnos matriculados en colegios privados concertados y no concertados y su distribución por tipo de enseñanza y por zonas geográficas Evolución del volumen de negocio de los colegios privados y distribución por tipo de centro Balance, cuenta de pérdidas y ganancias, ratios de rentabilidad y otros ratios económico-financieros agregados de las principales sociedades gestoras Previsiones de evolución del mercado Número, localización y tipo de colegio (concertado, no concertado) de los centros gestionados por las principales empresas/grupos Facturación y cuotas de mercado de las principales empresas/grupos Resultados financieros individuales de las principales sociedades gestoras: balance, cuenta de pérdidas y ganancias, ratios de rentabilidad y otros ratios económico-financieros Empresas analizadas BRITISH EDUCATION MANAGEMENT, S.L. BRITISH SCHOOL OF ALICANTE, S.A. -

Entidades Con Convenio De Colaboración Con La Uned

Vicerrectorado de Estudiantes y Emprendimiento Servicio de Acceso a la Universidad UNED-Application Service for International Students in Spain ENTIDADES CON CONVENIO DE COLABORACIÓN CON LA UNED PARA LA GESTIÓN DEL ACCESO Y ADMISIÓN DE ESTUDIANTES DE SISTEMAS EDUCATIVOS INTERNACIONALES, A LAS UNIVERSIDADES ESPAÑOLAS SISTEMA EDUCATIVO BRITÁNICO SIXTH FORM 21 - MADRID CHINA BEIJING SHANGHE WISE EDUCATION CONSULTING CO CHINA CONSULTING NEW CENTURY - MADRID CHINA DE JIA EDUCATION - MADRID CHINA EDUEUROPE - CÁDIZ CHINA FUNDACIÓN ESTUDIO, TURISMO Y DEPORTE - PALENCIA CHINA IDEALAR - MADRID CHINA INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ABROAD - MADRID CHINA MANYOO CONSULTING - MADRID CHINA Ñ CONSULTORÍA EDUCATIVA CHINA ESPAÑA - MADRID CHINA OEW - BARCELONA CHINA SHANGHAI SUNWISE INFO TECH - MADRID CHINA UNIMIK - VALENCIA CHINA ZEUMAT - ZARAGOZA CHINA Y OTROS GESTIÓN EDUCATIVA CONSULTORES - MADRID ECUATORIANO ECUADORGLOBAL FRANCÉS STUDENT’S MOBILITY - IVRY SUR SEINE (FRANCIA) PORTUGUÉS CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE ESPAÑOL DE OPORTO PORTUGUÉS FUN LANGUAGES OEIRAS - LISBOA PORTUGUÉS KIDS CLUB - GUARDA (PORTUGAL) PORTUGUÉS THE ANGLOPHIL CENTRE - AVEIRO (PORTUGAL) VARIOS SISTEMAS ACADEMIA ACCEDE - MADRID VARIOS SISTEMAS ACADEMIA ADOS - ALICANTE VARIOS SISTEMAS ACADEMIA ALBA - MURCIA VARIOS SISTEMAS ACADEMIA ALHAMBRA EDUCASA - (MARRUECOS) VARIOS SISTEMAS ACADEMIA AVENIDA ANDALUCÍA - MÁLAGA VARIOS SISTEMAS ACADEMIA BRAVOSOL - MADRID VARIOS SISTEMAS ACADEMIA CARLOS DE LA HOZ - BADAJOZ VARIOS SISTEMAS ACADEMIA GUIU - BARCELONA VARIOS SISTEMAS ACADEMIA LA LLIBRETA - VALENCIA -

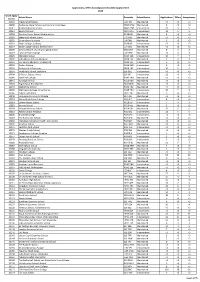

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2020

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2020 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 4 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 12 5 5 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 12 3 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained 3 <3 <3 10023 Stoke College, Sudbury CO10 8JE Independent <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 9 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 23 4 3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 35 7 7 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 5 3 3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 5 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 8 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 16 6 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 12 <3 <3 10040 Garth Hill College RG42 2AD Maintained <3 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 30 7 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10048