Certificate Transparency V2.1A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Frankencerts for Automated Adversarial Testing of Certificate

Using Frankencerts for Automated Adversarial Testing of Certificate Validation in SSL/TLS Implementations Chad Brubaker ∗ y Suman Janay Baishakhi Rayz Sarfraz Khurshidy Vitaly Shmatikovy ∗Google yThe University of Texas at Austin zUniversity of California, Davis Abstract—Modern network security rests on the Secure Sock- many open-source implementations of SSL/TLS are available ets Layer (SSL) and Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocols. for developers who need to incorporate SSL/TLS into their Distributed systems, mobile and desktop applications, embedded software: OpenSSL, NSS, GnuTLS, CyaSSL, PolarSSL, Ma- devices, and all of secure Web rely on SSL/TLS for protection trixSSL, cryptlib, and several others. Several Web browsers against network attacks. This protection critically depends on include their own, proprietary implementations. whether SSL/TLS clients correctly validate X.509 certificates presented by servers during the SSL/TLS handshake protocol. In this paper, we focus on server authentication, which We design, implement, and apply the first methodology for is the only protection against man-in-the-middle and other large-scale testing of certificate validation logic in SSL/TLS server impersonation attacks, and thus essential for HTTPS implementations. Our first ingredient is “frankencerts,” synthetic and virtually any other application of SSL/TLS. Server authen- certificates that are randomly mutated from parts of real cer- tication in SSL/TLS depends entirely on a single step in the tificates and thus include unusual combinations of extensions handshake protocol. As part of its “Server Hello” message, and constraints. Our second ingredient is differential testing: if the server presents an X.509 certificate with its public key. -

Analysis of SSL Certificate Reissues and Revocations in the Wake

Analysis of SSL Certificate Reissues and Revocations in the Wake of Heartbleed Liang Zhang David Choffnes Dave Levin Tudor Dumitra¸s Northeastern University Northeastern University University of Maryland University of Maryland [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Alan Mislove Aaron Schulman Christo Wilson Northeastern University Stanford University Northeastern University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Categories and Subject Descriptors Central to the secure operation of a public key infrastruc- C.2.2 [Computer-Communication Networks]: Net- ture (PKI) is the ability to revoke certificates. While much work Protocols; C.2.3 [Computer-Communication Net- of users' security rests on this process taking place quickly, works]: Network Operations; E.3 [Data Encryption]: in practice, revocation typically requires a human to decide Public Key Cryptosystems, Standards to reissue a new certificate and revoke the old one. Thus, having a proper understanding of how often systems admin- istrators reissue and revoke certificates is crucial to under- Keywords standing the integrity of a PKI. Unfortunately, this is typi- Heartbleed; SSL; TLS; HTTPS; X.509; Certificates; Reissue; cally difficult to measure: while it is relatively easy to deter- Revocation; Extended validation mine when a certificate is revoked, it is difficult to determine whether and when an administrator should have revoked. In this paper, we use a recent widespread security vul- 1. INTRODUCTION nerability as a natural experiment. Publicly announced in Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) and Transport Layer Secu- April 2014, the Heartbleed OpenSSL bug, potentially (and rity (TLS)1 are the de-facto standards for securing Internet undetectably) revealed servers' private keys. -

Analysis of SSL Certificate Reissues And

Analysis of SSL Certificate Reissues and Revocations in the Wake of Heartbleed Liang Zhang David Choffnes Dave Levin Tudor Dumitra¸s Northeastern University Northeastern University University of Maryland University of Maryland [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Alan Mislove Aaron Schulman Christo Wilson Northeastern University Stanford University Northeastern University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Categories and Subject Descriptors Central to the secure operation of a public key infrastruc- C.2.2 [Computer-Communication Networks]: Net- ture (PKI) is the ability to revoke certificates. While much work Protocols; C.2.3 [Computer-Communication Net- of users' security rests on this process taking place quickly, works]: Network Operations; E.3 [Data Encryption]: in practice, revocation typically requires a human to decide Public Key Cryptosystems, Standards to reissue a new certificate and revoke the old one. Thus, having a proper understanding of how often systems admin- istrators reissue and revoke certificates is crucial to under- Keywords standing the integrity of a PKI. Unfortunately, this is typi- Heartbleed; SSL; TLS; HTTPS; X.509; Certificates; Reissue; cally difficult to measure: while it is relatively easy to deter- Revocation; Extended validation mine when a certificate is revoked, it is difficult to determine whether and when an administrator should have revoked. In this paper, we use a recent widespread security vul- 1. INTRODUCTION nerability as a natural experiment. Publicly announced in Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) and Transport Layer Secu- April 2014, the Heartbleed OpenSSL bug, potentially (and rity (TLS)1 are the de-facto standards for securing Internet undetectably) revealed servers' private keys. -

Certificate Transparency Using Blockchain

Certicate Transparency Using Blockchain D S V Madala1, Mahabir Prasad Jhanwar1, and Anupam Chattopadhyay2 1Department of Computer Science. Ashoka University, India 2School of Computer Science and Engineering. NTU, Singapore Abstract The security of web communication via the SSL/TLS protocols relies on safe distribu- tions of public keys associated with web domains in the form of X:509 certicates. Certicate authorities (CAs) are trusted third parties that issue these certicates. However, the CA ecosystem is fragile and prone to compromises. Starting with Google's Certicate Trans- parency project, a number of research works have recently looked at adding transparency for better CA accountability, eectively through public logs of all certicates issued by certica- tion authorities, to augment the current X:509 certicate validation process into SSL/TLS. In this paper, leveraging recent progress in blockchain technology, we propose a novel system, called CTB, that makes it impossible for a CA to issue a certicate for a domain without obtaining consent from the domain owner. We further make progress to equip CTB with certicate revocation mechanism. We implement CTB using IBM's Hyperledger Fabric blockchain platform. CTB's smart contract, written in Go, is provided for complete reference. 1 Introduction The overwhelming adoption of SSL/TLS (Secure Socket Layer/Transport Layer Security Proto- cols) [4, 33] for most HTTP trac has transformed the Internet into a communication platform with strong measures of condentiality and integrity. It is one -

Public Key Distribution (And Certifications)

Lecture 12 Public Key Distribution (and Certifications) (Chapter 15 in KPS) 1 A Typical KDC-based Key Distribution Scenario KDC = Key Distribution Center KDC EK[X] = Encryption of X with key K (1) Request|B|N1 (2) E [K |Request|N |E (K ,A)] Ka s 1 Kb s (3) E [K ,A] Kb s A (4) E [A,N ] Ks 2 B Notes: (5) E [f(N )] Ks 2 • Msg2 is tied to Msg1 • Msg2 is fresh/new • Msg3 is possibly old * • Msg1 is possibly old (KDC doesn’t authenticate Alice) • Bob authenticates Alice • Bob authenticates KDC 2 • Alice DOES NOT authenticate Bob Public Key Distribution • General Schemes: • Public announcement (e.g., in a newsgroup or email message) • Can be forged • Publicly available directory • Can be tampered with • Public-key certificates (PKCs) issued by trusted off-line Certification Authorities (CAs) 3 Certification Authorities • Certification Authority (CA): binds public key to a specific entity • Each entity (user, host, etc.) registers its public key with CA. • Bob provides “proof of identity” to CA. • CA creates certificate binding Bob to this public key. • Certificate containing Bob’s public key digitally signed by CA: CA says: “this is Bob’s public key” Bob’s digital PK public signature B key PK B certificate for Bob’s CA Bob’s private SK public key, signed by identifying key CA CA information 4 Certification Authority • When Alice wants to get Bob’s public key: • Get Bob’s certificate (from Bob or elsewhere) • Using CA’s public key verify the signature on Bob’s certificate • Check for expiration • Check for revocation (we’ll talk about this later) • Extract Bob’s public key Bob’s PK B digital Public signature Key PK B CA Public PK Key CA 5 A Certificate Contains • Serial number (unique to issuer) • Info about certificate owner, including algorithm and key value itself (not shown) • info about certificate issuer • valid dates • digital signature by issuer 6 Reflection Attack and a Fix • Original Protocol 1. -

Certificate Transparency Description

Certificate Transparency Description Certificate Transparency is an experimental protocol for publicly logging the existence of Transport Layer Security (TLS) certificates as they are issued or observed, in a manner that allows anyone to audit certificate authority (CA) activity and notice the issuance of suspect certificates as well as to audit the certificate logs themselves. The intent is that eventually clients would refuse to honor certificates that do not appear in a log, effectively forcing CAs to add all issued certificates to the logs. Logs are network services that implement the protocol operations for submissions and queries that are defined in this document. (q.v. IETF RFC 6962) The objectives are described as: Make it very difficult for a CA to issue a TLS certificate for a domain without the certificate being visible to the owner of that domain. Provide an open auditing and monitoring system that lets any domain owner or CA determine whether certificates have been mistakenly or maliciously issued. Protect users from being duped by certificates that were mistakenly or maliciously issued. (q.v. https://www.certificate-transparency.org/what-is-ct) Note that end user TLS clients are not responsible for validating CT logs, all they need to do is enforce a requirement that certificates must have extensions that show that they were issued under these procedures by validating a Signed Certificate Timestamp (SCT) data object presented with the TLS server certificate. Monitors and Auditors have the primary responsibility of detecting anomalous certificates that were never submitted to the logs. According to wikipedia, the implementation status of the standard is as follows: Google launched its first certificate transparency log in March 2013. -

Trust Me, I'm a Root CA! Analyzing SSL Root Cas in Modern Browsers

Trust me, I’m a Root CA! Analyzing SSL Root CAs in modern Browsers and Operating Systems Tariq Fadai, Sebastian Schrittwieser Peter Kieseberg, Martin Mulazzani Josef Ressel Center for Unified Threat Intelligence SBA Research, on Targeted Attacks, Austria St. Poelten University of Applied Sciences, Austria Email: [pkieseberg,mmulazzani]@sba-research.org Email: [is101005,sebastian.schrittwieser]@fhstp.ac.at Abstract—The security and privacy of our online communi- tected communications is dependent on the trustworthiness cations heavily relies on the entity authentication mechanisms of various companies and governments. It is therefore of provided by SSL. Those mechanisms in turn heavily depend interest to find out which companies we implicitly trust just on the trustworthiness of a large number of companies and governmental institutions for attestation of the identity of SSL by using different operating system platforms or browsers. services providers. In order to offer a wide and unobstructed In this paper an analysis of the root certificates included in availability of SSL-enabled services and to remove the need various browsers and operating systems is introduced. Our to make a large amount of trust decisions from their users, main contributions are: operating systems and browser manufactures include lists of certification authorities which are trusted for SSL entity • We performed an in-depth analysis of Root Certifi- authentication by their products. This has the problematic cate Authorities in modern operating systems and web effect that users of such browsers and operating systems browsers implicitly trust those certification authorities with the privacy • We correlated them against a variety of trust indexes of their communications while they might not even realize it. -

The Most Dangerous Code in the World: Validating SSL Certificates In

The Most Dangerous Code in the World: Validating SSL Certificates in Non-Browser Software Martin Georgiev Subodh Iyengar Suman Jana The University of Texas Stanford University The University of Texas at Austin at Austin Rishita Anubhai Dan Boneh Vitaly Shmatikov Stanford University Stanford University The University of Texas at Austin ABSTRACT cations. The main purpose of SSL is to provide end-to-end security SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) is the de facto standard for secure In- against an active, man-in-the-middle attacker. Even if the network ternet communications. Security of SSL connections against an is completely compromised—DNS is poisoned, access points and active network attacker depends on correctly validating public-key routers are controlled by the adversary, etc.—SSL is intended to certificates presented when the connection is established. guarantee confidentiality, authenticity, and integrity for communi- We demonstrate that SSL certificate validation is completely bro- cations between the client and the server. Authenticating the server is a critical part of SSL connection es- ken in many security-critical applications and libraries. Vulnerable 1 software includes Amazon’s EC2 Java library and all cloud clients tablishment. This authentication takes place during the SSL hand- based on it; Amazon’s and PayPal’s merchant SDKs responsible shake, when the server presents its public-key certificate. In order for transmitting payment details from e-commerce sites to payment for the SSL connection to be secure, the client must carefully verify gateways; integrated shopping carts such as osCommerce, ZenCart, that the certificate has been issued by a valid certificate authority, Ubercart, and PrestaShop; AdMob code used by mobile websites; has not expired (or been revoked), the name(s) listed in the certifi- Chase mobile banking and several other Android apps and libraries; cate match(es) the name of the domain that the client is connecting Java Web-services middleware—including Apache Axis, Axis 2, to, and perform several other checks [14, 15]. -

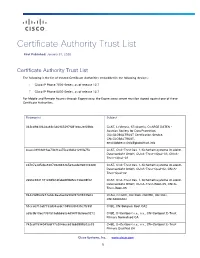

Certificate Authority Trust List

Certificate Authority Trust List First Published: January 31, 2020 Certificate Authority Trust List The following is the list of trusted Certificate Authorities embedded in the following devices: Cisco IP Phone 7800 Series, as of release 12.7 Cisco IP Phone 8800 Series, as of release 12.7 For Mobile and Remote Access through Expressway, the Expressway server must be signed against one of these Certificate Authorities. Fingerprint Subject 342cd9d3062da48c346965297f081ebc2ef68fdc C=AT, L=Vienna, ST=Austria, O=ARGE DATEN - Austrian Society for Data Protection, OU=GLOBALTRUST Certification Service, CN=GLOBALTRUST, [email protected] 4caee38931d19ae73b31aa75ca33d621290fa75e C=AT, O=A-Trust Ges. f. Sicherheitssysteme im elektr. Datenverkehr GmbH, OU=A-Trust-nQual-03, CN=A- Trust-nQual-03 cd787a3d5cba8207082848365e9acde9683364d8 C=AT, O=A-Trust Ges. f. Sicherheitssysteme im elektr. Datenverkehr GmbH, OU=A-Trust-Qual-02, CN=A- Trust-Qual-02 2e66c9841181c08fb1dfabd4ff8d5cc72be08f02 C=AT, O=A-Trust Ges. f. Sicherheitssysteme im elektr. Datenverkehr GmbH, OU=A-Trust-Root-05, CN=A- Trust-Root-05 84429d9fe2e73a0dc8aa0ae0a902f2749933fe02 C=AU, O=GOV, OU=DoD, OU=PKI, OU=CAs, CN=ADOCA02 51cca0710af7733d34acdc1945099f435c7fc59f C=BE, CN=Belgium Root CA2 a59c9b10ec7357515abb660c4d94f73b9e6e9272 C=BE, O=Certipost s.a., n.v., CN=Certipost E-Trust Primary Normalised CA 742cdf1594049cbf17a2046cc639bb3888e02e33 C=BE, O=Certipost s.a., n.v., CN=Certipost E-Trust Primary Qualified CA Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com 1 Certificate Authority -

Exploring CA Certificate Control

What’s in a Name? Exploring CA Certificate Control Zane Ma† Joshua Mason† Manos Antonakakis‡ Zakir Durumeric§ Michael Bailey† ‡Georgia Institute of Technology §Stanford University †University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Abstract other transgressions, prompted root store operators to begin discussions about removing trust in WoSign certificates. In TLS clients rely on a supporting PKI in which certificate July 2016, a new discovery revealed that StartCom, a seem- authorities (CAs)—trusted organizations—validate and cryp- ingly unaffiliated CA in Israel, was able to issue certificates tographically attest to the identities of web servers. A client’s signed by WoSign (a Chinese company). A deeper investiga- confidence that it is connecting to the right server depends tion of the incident eventually revealed that “the transaction entirely on the set of CAs that it trusts. However, as we demon- which completed the chain to give WoSign 100% ownership strate in this work, the identity specified in CA certificates is of StartCom completed on November 1st 2015” [59]. Further frequently inaccurate due to lax naming requirements, owner- evidence emerged that StartCom’s CA certificates had likely ship changes, and long-lived certificates. This not only mud- been integrated with WoSign operations as early as December dles client selection of trusted CAs, but also prevents PKI 2015 [56], when the removal of WoSign certificates from root operators and researchers from correctly attributing CA cer- stores appeared imminent. WoSign’s stealthy acquisition of tificate issues to CA organizations. To help Web PKI par- StartCom emphasizes the importance of transparency around ticipants understand the organizations that control each CA operational CA control for a secure web. -

Certificate Transparency in the Wild:Exploring the Reliability Of

Certificate Transparency in the Wild: Exploring the Reliability of Monitors Bingyu Li1;2;3, Jingqiang Lin1;2;3∗, Fengjun Li4, Qiongxiao Wang1;2, Qi Li5, Jiwu Jing6, Congli Wang1;2;3 1. State Key Laboratory of Information Security, Institute of Information Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences 2. Data Assurance and Communication Security Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences 3. School of Cyber Security, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences 4. Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, the University of Kansas, USA 5. Institute for Network Sciences and Cyberspace, Tsinghua University, China 6. School of Computer Science and Technology, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences {libingyu, linjingqiang}@iie.ac.cn, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS To detect fraudulent TLS server certificates and improve the ac- Certificate Transparency; Trust Management countability of certification authorities (CAs), certificate transparen- cy (CT) is proposed to record certificates in publicly-visible logs, from which the monitors fetch all certificates and watch for suspi- ACM Reference Format: cious ones. However, if the monitors, either domain owners them- Bingyu Li, Jingqiang Lin, Fengjun Li, Qiongxiao Wang, Qi Li, Jiwu Jing, and selves or third-party services, fail to return a complete set of cer- Congli Wang. 2019. Certificate Transparency in the Wild: Exploring the tificates issued for a domain of interest, potentially fraudulent cer- Reliability of Monitors. In 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and tificates may not be detected and then the CT framework becomes Communications Security (CCS’19), November 11–15, 2019, London, United less reliable. -

Digicert Certificate Policy V.5.4

DigiCert Certificate Policy DigiCert, Inc. Version 5.4 September 29, 20202 801 N. Thanksgiving Way Suite 500 Lehi, UT 84043 USA Tel: 1-801-877-2100 Fax: 1-801-705-0481 www.digicert.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1. OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. DOCUMENT NAME AND IDENTIFICATION ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.3. PKI PARTICIPANTS ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................10 1.3.1. DigiCert Policy Authority and Certification Authorities ................................................................................................................................11 1.3.2. Registration Authorities ..............................................................................................................................................................................................11 1.3.3. Subscribers .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................11