Certificate Transparency Description

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Frankencerts for Automated Adversarial Testing of Certificate

Using Frankencerts for Automated Adversarial Testing of Certificate Validation in SSL/TLS Implementations Chad Brubaker ∗ y Suman Janay Baishakhi Rayz Sarfraz Khurshidy Vitaly Shmatikovy ∗Google yThe University of Texas at Austin zUniversity of California, Davis Abstract—Modern network security rests on the Secure Sock- many open-source implementations of SSL/TLS are available ets Layer (SSL) and Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocols. for developers who need to incorporate SSL/TLS into their Distributed systems, mobile and desktop applications, embedded software: OpenSSL, NSS, GnuTLS, CyaSSL, PolarSSL, Ma- devices, and all of secure Web rely on SSL/TLS for protection trixSSL, cryptlib, and several others. Several Web browsers against network attacks. This protection critically depends on include their own, proprietary implementations. whether SSL/TLS clients correctly validate X.509 certificates presented by servers during the SSL/TLS handshake protocol. In this paper, we focus on server authentication, which We design, implement, and apply the first methodology for is the only protection against man-in-the-middle and other large-scale testing of certificate validation logic in SSL/TLS server impersonation attacks, and thus essential for HTTPS implementations. Our first ingredient is “frankencerts,” synthetic and virtually any other application of SSL/TLS. Server authen- certificates that are randomly mutated from parts of real cer- tication in SSL/TLS depends entirely on a single step in the tificates and thus include unusual combinations of extensions handshake protocol. As part of its “Server Hello” message, and constraints. Our second ingredient is differential testing: if the server presents an X.509 certificate with its public key. -

Quantitative Verification of Gossip Protocols for Certificate Transparency

QUANTITATIVE VERIFICATION OF GOSSIP PROTOCOLS FOR CERTIFICATE TRANSPARENCY by MICHAEL COLIN OXFORD A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Computer Science College of Engineering and Physical Sciences University of Birmingham December 2020 2 Abstract Certificate transparency is a promising solution to publicly auditing Internet certificates. However, there is the potential of split-world attacks, where users are directed to fake versions of the log where they may accept fraudulent certificates. To ensure users are seeing the same version of a log, gossip protocols have been designed where users share and verify log-generated data. This thesis proposes a methodology of evaluating such protocols using probabilistic model checking, a collection of techniques for formally verifying properties of stochastic systems. It also describes the approach to modelling and verifying the protocols and analysing several aspects, including the success rate of detecting inconsistencies in gossip messages and its efficiency in terms of bandwidth. This thesis also compares different protocol variants and suggests ways to augment the protocol to improve performances, using model checking to verify the claims. To address uncertainty and unscalability issues within the models, this thesis shows how to transform models by allowing the probability of certain events to lie within a range of values, and abstract them to make the verification process more efficient. Lastly, by parameterising the models, this thesis shows how to search possible model configurations to find the worst-case behaviour for certain formal properties. 4 Acknowledgements To Auntie Mary and Nanny Lee. Writing this thesis could not have been accomplished after four tumultuous years alone. -

Let's Encrypt: 30,229 Jan, 2018 | Let's Encrypt: 18,326 Jan, 2016 | Let's Encrypt: 330 Feb, 2017 | Let's Encrypt: 8,199

Let’s Encrypt: An Automated Certificate Authority to Encrypt the Entire Web Josh Aas∗ Richard Barnes∗ Benton Case Let’s Encrypt Cisco Stanford University Zakir Durumeric Peter Eckersley∗ Alan Flores-López Stanford University Electronic Frontier Foundation Stanford University J. Alex Halderman∗† Jacob Hoffman-Andrews∗ James Kasten∗ University of Michigan Electronic Frontier Foundation University of Michigan Eric Rescorla∗ Seth Schoen∗ Brad Warren∗ Mozilla Electronic Frontier Foundation Electronic Frontier Foundation ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION Let’s Encrypt is a free, open, and automated HTTPS certificate au- HTTPS [78] is the cryptographic foundation of the Web, providing thority (CA) created to advance HTTPS adoption to the entire Web. an encrypted and authenticated form of HTTP over the TLS trans- Since its launch in late 2015, Let’s Encrypt has grown to become the port [79]. When HTTPS was introduced by Netscape twenty-five world’s largest HTTPS CA, accounting for more currently valid cer- years ago [51], the primary use cases were protecting financial tificates than all other browser-trusted CAs combined. By January transactions and login credentials, but users today face a growing 2019, it had issued over 538 million certificates for 223 million do- range of threats from hostile networks—including mass surveil- main names. We describe how we built Let’s Encrypt, including the lance and censorship by governments [99, 106], consumer profiling architecture of the CA software system (Boulder) and the structure and ad injection by ISPs [30, 95], and insertion of malicious code of the organization that operates it (ISRG), and we discuss lessons by network devices [68]—which make HTTPS important for prac- learned from the experience. -

Analysis of SSL Certificate Reissues and Revocations in the Wake

Analysis of SSL Certificate Reissues and Revocations in the Wake of Heartbleed Liang Zhang David Choffnes Dave Levin Tudor Dumitra¸s Northeastern University Northeastern University University of Maryland University of Maryland [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Alan Mislove Aaron Schulman Christo Wilson Northeastern University Stanford University Northeastern University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Categories and Subject Descriptors Central to the secure operation of a public key infrastruc- C.2.2 [Computer-Communication Networks]: Net- ture (PKI) is the ability to revoke certificates. While much work Protocols; C.2.3 [Computer-Communication Net- of users' security rests on this process taking place quickly, works]: Network Operations; E.3 [Data Encryption]: in practice, revocation typically requires a human to decide Public Key Cryptosystems, Standards to reissue a new certificate and revoke the old one. Thus, having a proper understanding of how often systems admin- istrators reissue and revoke certificates is crucial to under- Keywords standing the integrity of a PKI. Unfortunately, this is typi- Heartbleed; SSL; TLS; HTTPS; X.509; Certificates; Reissue; cally difficult to measure: while it is relatively easy to deter- Revocation; Extended validation mine when a certificate is revoked, it is difficult to determine whether and when an administrator should have revoked. In this paper, we use a recent widespread security vul- 1. INTRODUCTION nerability as a natural experiment. Publicly announced in Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) and Transport Layer Secu- April 2014, the Heartbleed OpenSSL bug, potentially (and rity (TLS)1 are the de-facto standards for securing Internet undetectably) revealed servers' private keys. -

Certificate Transparency: New Part of PKI Infrastructure

Certificate transparency: New part of PKI infrastructure A presentation by Dmitry Belyavsky, TCI ENOG 7 Moscow, May 26-27, 2014 About PKI *) *) PKI (public-key infrastructure) is a set of hardware, software, people, policies, and procedures needed to create, manage, distribute, use, store, and revoke digital certificates Check the server certificate The server certificate signed correctly by any of them? Many trusted CAs NO YES Everything seems to We warn the user be ok! DigiNotar case OCSP requests for the fake *.google.com certificate Source: FOX-IT, Interim Report, http://cryptome.org/0005/diginotar-insec.pdf PKI: extra trust Independent Trusted PKI source certificate DANE (RFC 6698) Certificate pinning Limited browsers support Mozilla Certificate Patrol, Chrome cache for Google certificates Certificate transparency (RFC 6962) Inspired by Google (Support in Chrome appeared) One of the authors - Ben Laurie (OpenSSL Founder) CA support – Comodo Certificate Transparency: how it works • Log accepts cert => SCT Client • Is SCT present and signed correctly? Client • Is SCT present and signed correctly? Auditor • Does log server behave correctly? Monitor • Any suspicious certs? Certificate Transparency: how it works Source: http://www.certificate-transparency.org Certificate Transparency how it works Source: http://www.certificate-transparency.org Certificate Transparency current state Google Chrome Support (33+) http://www.certificate-transparency.org/certificate-transparency-in-chrome Google Cert EV plan http://www.certificate-transparency.org/ev-ct-plan Certificate Transparency current state Open source code 2 pilot logs Certificate Transparency: protect from what? SAVE from MITM attack ü Warning from browser ü Site owner can watch logs for certs Do NOT SAVE from HEARTBLEED! Certificate transparency and Russian GOST crypto Russian GOST does not save from the MITM attack Algorithm SHA-256 >>> GOSTR34.11-2012 Key >>> GOST R 34.10-2012 Q&A Questions? Drop ‘em at: [email protected] . -

An Empirical Analysis of Email Delivery Security

Neither Snow Nor Rain Nor MITM . An Empirical Analysis of Email Delivery Security Zakir Durumeric† David Adrian† Ariana Mirian† James Kasten† Elie Bursztein‡ Nicolas Lidzborski‡ Kurt Thomas‡ Vijay Eranti‡ Michael Bailey§ J. Alex Halderman† † University of Michigan ‡ Google, Inc. § University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign {zakir, davadria, amirian, jdkasten, jhalderm}@umich.edu {elieb, nlidz, kurtthomas, vijaye}@google.com [email protected] ABSTRACT tolerate unprotected communication at the expense of user security. The SMTP protocol is responsible for carrying some of users’ most Equally problematic, users face a medium that fails to alert clients intimate communication, but like other Internet protocols, authen- when messages traverse an insecure path and that lacks a mechanism tication and confidentiality were added only as an afterthought. In to enforce strict transport security. this work, we present the first report on global adoption rates of In this work, we measure the global adoption of SMTP security SMTP security extensions, including: STARTTLS, SPF, DKIM, and extensions and the resulting impact on end users. Our study draws DMARC. We present data from two perspectives: SMTP server from two unique perspectives: longitudinal SMTP connection logs configurations for the Alexa Top Million domains, and over a year spanning from January 2014 to April 2015 for Gmail, one of the of SMTP connections to and from Gmail. We find that the top mail world’s largest mail providers; and a snapshot of SMTP server providers (e.g., Gmail, Yahoo, -

Analysis of SSL Certificate Reissues And

Analysis of SSL Certificate Reissues and Revocations in the Wake of Heartbleed Liang Zhang David Choffnes Dave Levin Tudor Dumitra¸s Northeastern University Northeastern University University of Maryland University of Maryland [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Alan Mislove Aaron Schulman Christo Wilson Northeastern University Stanford University Northeastern University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Categories and Subject Descriptors Central to the secure operation of a public key infrastruc- C.2.2 [Computer-Communication Networks]: Net- ture (PKI) is the ability to revoke certificates. While much work Protocols; C.2.3 [Computer-Communication Net- of users' security rests on this process taking place quickly, works]: Network Operations; E.3 [Data Encryption]: in practice, revocation typically requires a human to decide Public Key Cryptosystems, Standards to reissue a new certificate and revoke the old one. Thus, having a proper understanding of how often systems admin- istrators reissue and revoke certificates is crucial to under- Keywords standing the integrity of a PKI. Unfortunately, this is typi- Heartbleed; SSL; TLS; HTTPS; X.509; Certificates; Reissue; cally difficult to measure: while it is relatively easy to deter- Revocation; Extended validation mine when a certificate is revoked, it is difficult to determine whether and when an administrator should have revoked. In this paper, we use a recent widespread security vul- 1. INTRODUCTION nerability as a natural experiment. Publicly announced in Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) and Transport Layer Secu- April 2014, the Heartbleed OpenSSL bug, potentially (and rity (TLS)1 are the de-facto standards for securing Internet undetectably) revealed servers' private keys. -

Certificate Transparency Using Blockchain

Certicate Transparency Using Blockchain D S V Madala1, Mahabir Prasad Jhanwar1, and Anupam Chattopadhyay2 1Department of Computer Science. Ashoka University, India 2School of Computer Science and Engineering. NTU, Singapore Abstract The security of web communication via the SSL/TLS protocols relies on safe distribu- tions of public keys associated with web domains in the form of X:509 certicates. Certicate authorities (CAs) are trusted third parties that issue these certicates. However, the CA ecosystem is fragile and prone to compromises. Starting with Google's Certicate Trans- parency project, a number of research works have recently looked at adding transparency for better CA accountability, eectively through public logs of all certicates issued by certica- tion authorities, to augment the current X:509 certicate validation process into SSL/TLS. In this paper, leveraging recent progress in blockchain technology, we propose a novel system, called CTB, that makes it impossible for a CA to issue a certicate for a domain without obtaining consent from the domain owner. We further make progress to equip CTB with certicate revocation mechanism. We implement CTB using IBM's Hyperledger Fabric blockchain platform. CTB's smart contract, written in Go, is provided for complete reference. 1 Introduction The overwhelming adoption of SSL/TLS (Secure Socket Layer/Transport Layer Security Proto- cols) [4, 33] for most HTTP trac has transformed the Internet into a communication platform with strong measures of condentiality and integrity. It is one -

Public Key Distribution (And Certifications)

Lecture 12 Public Key Distribution (and Certifications) (Chapter 15 in KPS) 1 A Typical KDC-based Key Distribution Scenario KDC = Key Distribution Center KDC EK[X] = Encryption of X with key K (1) Request|B|N1 (2) E [K |Request|N |E (K ,A)] Ka s 1 Kb s (3) E [K ,A] Kb s A (4) E [A,N ] Ks 2 B Notes: (5) E [f(N )] Ks 2 • Msg2 is tied to Msg1 • Msg2 is fresh/new • Msg3 is possibly old * • Msg1 is possibly old (KDC doesn’t authenticate Alice) • Bob authenticates Alice • Bob authenticates KDC 2 • Alice DOES NOT authenticate Bob Public Key Distribution • General Schemes: • Public announcement (e.g., in a newsgroup or email message) • Can be forged • Publicly available directory • Can be tampered with • Public-key certificates (PKCs) issued by trusted off-line Certification Authorities (CAs) 3 Certification Authorities • Certification Authority (CA): binds public key to a specific entity • Each entity (user, host, etc.) registers its public key with CA. • Bob provides “proof of identity” to CA. • CA creates certificate binding Bob to this public key. • Certificate containing Bob’s public key digitally signed by CA: CA says: “this is Bob’s public key” Bob’s digital PK public signature B key PK B certificate for Bob’s CA Bob’s private SK public key, signed by identifying key CA CA information 4 Certification Authority • When Alice wants to get Bob’s public key: • Get Bob’s certificate (from Bob or elsewhere) • Using CA’s public key verify the signature on Bob’s certificate • Check for expiration • Check for revocation (we’ll talk about this later) • Extract Bob’s public key Bob’s PK B digital Public signature Key PK B CA Public PK Key CA 5 A Certificate Contains • Serial number (unique to issuer) • Info about certificate owner, including algorithm and key value itself (not shown) • info about certificate issuer • valid dates • digital signature by issuer 6 Reflection Attack and a Fix • Original Protocol 1. -

Trust Me, I'm a Root CA! Analyzing SSL Root Cas in Modern Browsers

Trust me, I’m a Root CA! Analyzing SSL Root CAs in modern Browsers and Operating Systems Tariq Fadai, Sebastian Schrittwieser Peter Kieseberg, Martin Mulazzani Josef Ressel Center for Unified Threat Intelligence SBA Research, on Targeted Attacks, Austria St. Poelten University of Applied Sciences, Austria Email: [pkieseberg,mmulazzani]@sba-research.org Email: [is101005,sebastian.schrittwieser]@fhstp.ac.at Abstract—The security and privacy of our online communi- tected communications is dependent on the trustworthiness cations heavily relies on the entity authentication mechanisms of various companies and governments. It is therefore of provided by SSL. Those mechanisms in turn heavily depend interest to find out which companies we implicitly trust just on the trustworthiness of a large number of companies and governmental institutions for attestation of the identity of SSL by using different operating system platforms or browsers. services providers. In order to offer a wide and unobstructed In this paper an analysis of the root certificates included in availability of SSL-enabled services and to remove the need various browsers and operating systems is introduced. Our to make a large amount of trust decisions from their users, main contributions are: operating systems and browser manufactures include lists of certification authorities which are trusted for SSL entity • We performed an in-depth analysis of Root Certifi- authentication by their products. This has the problematic cate Authorities in modern operating systems and web effect that users of such browsers and operating systems browsers implicitly trust those certification authorities with the privacy • We correlated them against a variety of trust indexes of their communications while they might not even realize it. -

The Most Dangerous Code in the World: Validating SSL Certificates In

The Most Dangerous Code in the World: Validating SSL Certificates in Non-Browser Software Martin Georgiev Subodh Iyengar Suman Jana The University of Texas Stanford University The University of Texas at Austin at Austin Rishita Anubhai Dan Boneh Vitaly Shmatikov Stanford University Stanford University The University of Texas at Austin ABSTRACT cations. The main purpose of SSL is to provide end-to-end security SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) is the de facto standard for secure In- against an active, man-in-the-middle attacker. Even if the network ternet communications. Security of SSL connections against an is completely compromised—DNS is poisoned, access points and active network attacker depends on correctly validating public-key routers are controlled by the adversary, etc.—SSL is intended to certificates presented when the connection is established. guarantee confidentiality, authenticity, and integrity for communi- We demonstrate that SSL certificate validation is completely bro- cations between the client and the server. Authenticating the server is a critical part of SSL connection es- ken in many security-critical applications and libraries. Vulnerable 1 software includes Amazon’s EC2 Java library and all cloud clients tablishment. This authentication takes place during the SSL hand- based on it; Amazon’s and PayPal’s merchant SDKs responsible shake, when the server presents its public-key certificate. In order for transmitting payment details from e-commerce sites to payment for the SSL connection to be secure, the client must carefully verify gateways; integrated shopping carts such as osCommerce, ZenCart, that the certificate has been issued by a valid certificate authority, Ubercart, and PrestaShop; AdMob code used by mobile websites; has not expired (or been revoked), the name(s) listed in the certifi- Chase mobile banking and several other Android apps and libraries; cate match(es) the name of the domain that the client is connecting Java Web-services middleware—including Apache Axis, Axis 2, to, and perform several other checks [14, 15]. -

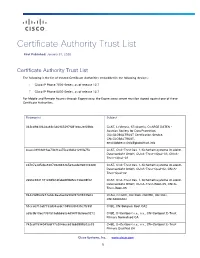

Certificate Authority Trust List

Certificate Authority Trust List First Published: January 31, 2020 Certificate Authority Trust List The following is the list of trusted Certificate Authorities embedded in the following devices: Cisco IP Phone 7800 Series, as of release 12.7 Cisco IP Phone 8800 Series, as of release 12.7 For Mobile and Remote Access through Expressway, the Expressway server must be signed against one of these Certificate Authorities. Fingerprint Subject 342cd9d3062da48c346965297f081ebc2ef68fdc C=AT, L=Vienna, ST=Austria, O=ARGE DATEN - Austrian Society for Data Protection, OU=GLOBALTRUST Certification Service, CN=GLOBALTRUST, [email protected] 4caee38931d19ae73b31aa75ca33d621290fa75e C=AT, O=A-Trust Ges. f. Sicherheitssysteme im elektr. Datenverkehr GmbH, OU=A-Trust-nQual-03, CN=A- Trust-nQual-03 cd787a3d5cba8207082848365e9acde9683364d8 C=AT, O=A-Trust Ges. f. Sicherheitssysteme im elektr. Datenverkehr GmbH, OU=A-Trust-Qual-02, CN=A- Trust-Qual-02 2e66c9841181c08fb1dfabd4ff8d5cc72be08f02 C=AT, O=A-Trust Ges. f. Sicherheitssysteme im elektr. Datenverkehr GmbH, OU=A-Trust-Root-05, CN=A- Trust-Root-05 84429d9fe2e73a0dc8aa0ae0a902f2749933fe02 C=AU, O=GOV, OU=DoD, OU=PKI, OU=CAs, CN=ADOCA02 51cca0710af7733d34acdc1945099f435c7fc59f C=BE, CN=Belgium Root CA2 a59c9b10ec7357515abb660c4d94f73b9e6e9272 C=BE, O=Certipost s.a., n.v., CN=Certipost E-Trust Primary Normalised CA 742cdf1594049cbf17a2046cc639bb3888e02e33 C=BE, O=Certipost s.a., n.v., CN=Certipost E-Trust Primary Qualified CA Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com 1 Certificate Authority