Wilderness Visitors, Experiences, and Management Preferences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woga Members 10-16-18.Xlsx

Land Based Outfitter CAMP WAHOO! - SUTTON, Mike & Stacy Member type Land Based Outfitter Phone: Web http://www.highcountry-outfitters.com Fax: Mailing 11320 Lambert Rd. Cle ellum WA 98922 Email: [email protected] Description A full service outfitter & kid's camp offering horse riding, pack trips, drop camps and more. Our rustic tent cabin camp is our summer home and base for our unique summer kid's camp. Campers get their own horse to care for and ride daily as they learn authentic mule packing techneiques. Region(s):6 Cascade Wilderness Outfitters - Steve Darwood Member type Land Based Outfitter Phone: 509-997-0155 Web http://www.CascadeWildernessOutfitters.com Fax: Mailing P.O. Box 103 Carlton, WA 98814 Email: Description Family & group oriented deluxe & standard summer pack trips, ride or hike. Dutch oven dinners. Hunting Drop Camps: Early Hunts: Andrews Creek - Spanish Camp - Cathedral Lakes - Remmel Lake - Apex Pass. General Hunts: Twisp River - Wolf Creek Areas Goat Hunts: by permit only in Methow 2 -2 Unit. Operating in the Pasayten Wilderness, Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness on Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest Region(s):3 Chinook Pass Outfitters & Guides, Inc. - Wilson, Paul Member type Land Based Outfitter Phone: 509-653-2633 Web http://www.chinookpass.com Fax: Mailing P.O. Box 1030 Naches, WA 98937 Email: [email protected] Description Horseback riding! Venture into the Wiliam O. Douglas or Norse Peak Wilderness-both bordering the Mt. Rainier National Park. Choose from hour rides to extended vacations. Fish the high lakes. Hunt deer, elk, bear, and goat with rifle, bow, muzzeloader or camera. Wenatchee National Forest (GMU #346-352-356). -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES Fall, 1984 2 The Wild Cascades PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE ONCE THE LINES ARE DRAWN, THE BATTLE IS NOT OVER The North Cascades Conservation Council has developed a reputation for consistent, hard-hitting, responsible action to protect wildland resources in the Washington Cascades. It is perhaps best known for leading the fight to preserve and protect the North Cascades in the North Cascades National Park, the Pasayten and Glacier Peak Wilderness Areas, and the Ross Lake and Lake Chelan National Recreation Areas. Despite the recent passage of the Washington Wilderness Act, many areas which deserve and require wilderness designation remain unprotected. One of the goals of the N3C must be to assure protection for these areas. In this issue of the Wild Cascades we have analyzed the Washington Wilderness Act to see what we won and what still hangs in the balance (page ). The N3C will continue to fight to establish new wilderness areas, but there is also a new challenge. Our expertise is increasingly being sought by government agencies to assist in developing appropriate management plans and to support them against attempts to undermine such plans. The invitation to participate more fully in management activities will require considerable effort, but it represents a challenge and an opportunity that cannot be ignored. If we are to meet this challenge we will need members who are either knowledgable or willing to learn about an issue and to guide the Board in its actions. The Spring issue of the Wild Cascades carried a center section with two requests: 1) volunteers to assist and guide the organization on various issues; and 2) payment of dues. -

Northeast Chapter Volunteer Hours Report for Year 2013-2014

BACK COUNTRY HORSEMEN OF WASHINGTON - Northeast Chapter Volunteer Hours Report for Year 2013-2014 Work Hours Other Hours Travel Equines Volunteer Name Project Agency District Basic Skilled LNT Admin Travel Vehicle Quant Days Description of work/ trail/trail head names Date Code Code Hours Hours Educ. Pub. Meet Time Miles Stock Used AGENCY & DISTRICT CODES Agency Code Agency Name District Codes for Agency A Cont'd A U.S.F.S. District Code District Name B State DNR OKNF Okanogan National Forest C State Parks and Highways Pasayten Wilderness D National Parks Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness E Education and LNT WNF Wenatchee National Forest F Dept. of Fish and Wildlife (State) Alpine Lakes Wilderness G Other Henry M Jackson Wilderness M Bureau of Land Management William O Douglas Wilderness T Private or Timber OLNF Olympic National Forest W County Mt Skokomish Wilderness Wonder Mt Wilderness District Codes for U.S.F.S. Agency Code A Colonel Bob Wilderness The Brothers Wilderness District Code District Name Buckhorn Wilderness CNF Colville National Forest UMNF Umatilla National Forest Salmo-Priest Wilderness Wenaha Tucannon Wilderness GPNF Gifford Pinchot National Forest IDNF Idaho Priest National Forest Goat Rocks Wilderness ORNF Oregon Forest Mt Adams Wilderness Indian Heaven Wilderness Trapper Wilderness District Codes for DNR Agency B Tatoosh Wilderness MBS Mt Baker Snoqualmie National Forest SPS South Puget Sound Region Glacier Peak Wilderness PCR Pacific Cascade Region Bolder River Wilderness OLR Olympic Region Clear Water Wilderness NWR Northwest Region Norse Peak Mt Baker Wilderness NER Northeast Region William O Douglas Wilderness SER Southeast Region Glacier View Wilderness Boulder River Wilderness VOLUNTEER HOURS GUIDELINES Volunteer Name 1. -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the MOUNT ADAMS VOLCANIC FIELD, CASCADE RANGE of SOUTHERN WASHINGTON by Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-2460 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MOUNT ADAMS VOLCANIC FIELD, CASCADE RANGE OF SOUTHERN WASHINGTON By Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein When I climbed Mount Adams {17-18 August 1945] about 1950 m (6400') most of the landscape is mantled I think I found the answer to the question of why men by dense forests and huckleberry thickets. Ten radial stake everything to reach these peaks, yet obtain no glaciers and the summit icecap today cover only about visible reward for their exhaustion... Man's greatest 2.5 percent (16 km2) of the cone, but in latest Pleis experience-the one that brings supreme exultation tocene time (25-11 ka) as much as 80 percent of Mount is spiritual, not physical. It is the catching of some Adams was under ice. The volcano is drained radially vision of the universe and translating it into a poem by numerous tributaries of the Klickitat, White Salmon, or work of art ... Lewis, and Cis pus Rivers (figs. 1, 2), all of which ulti William 0. Douglas mately flow into the Columbia. Most of Mount Adams and a vast area west of it are Of Men and Mountains administered by the U.S. Forest Service, which has long had the dual charge of protecting the Wilderness Area and of providing a network of logging roads almost INTRODUCTION everywhere else. The northeast quadrant of the moun One of the dominating peaks of the Pacific North tain, however, lies within a part of the Yakima Indian west, Mount Adams, stands astride the Cascade crest, Reservation that is open solely to enrolled members of towering 3 km above the surrounding valleys. -

Gifford Pinchot

THE FORGOTTEN FOREST: EXPLORING THE GIFFORD PINCHOT A Publication of the Washington Trails Association1 7A 9 4 8 3 1 10 7C 2 6 5 7B Cover Photo by Ira Spring 2 Table of Contents About Washington Trails Association Page 4 A Million Acres of outdoor Recreation Page 5 Before You Hit the Trail Page 6 Leave No Trace 101 Page 7 The Outings (see map on facing page) 1. Climbing Mount Adams Pages 8-9 2. Cross Country Skiing: Oldman Pass Pages 10-11 3. Horseback Riding: Quartz Creek Pages 12-13 4. Hiking: Juniper Ridge Pages 14-15 5. Backpacking the Pacific Crest Trail: Indian Heaven Wilderness Pages 16-17 6. Mountain Biking: Siouxon Trail Pages 18-19 7. Wildlife Observation: Pages 20-21 A. Goat Rocks Wilderness B. Trapper Creek Wilderness C. Lone Butte Wildlife Emphasis Area 8. Camping at Takhlakh Lake Pages 22-23 9. Fly Fishing the Cowlitz River Pages 24-25 10. Berry Picking in the Sawtooth Berry Fields Pages 26-27 Acknowledgements Page 28 How to Join WTA Page 29-30 Volunteer Trail Maintenance Page 31 Important Contacts Page 32 3 About Washington Trails Association Washington Trails Association (WTA) is the voice for hikers in Washington state. We advocate protection of hiking trails, take volunteers out to maintain them, and promote hiking as a healthy, fun way to explore Washington. Ira Spring and Louise Marshall co-founded WTA in 1966 as a response to the lack of a political voice for Washington’s hiking community. WTA is now the largest state-based hiker advocacy organization in the country, with over 5,500 members and more than 1,800 volunteers. -

Seattle Backpacking Washington Experience

Route Details for the Bronze Backpack, Silver Backpack, and Gold Backpack Award Badges Because the objective of the badges is to experience the variety of backpacking regions available in Washington, it’s not necessary to do each route exactly as described in the Routes & Places database or the references. A trip that follows approximately the same route with extensions or minor variations can be substituted. However, for routes whose descriptions include a “Key Experience” alternate routes must include that experience in order to qualify. Reference(s) Region Route Distance Gain Days Key Experience Notes WTA Books Olympic Peninsula Beaches 100 Classic Hikes in Washington, 2nd Edition #99 Olympic Coast North: The Shipwreck Coast 20.2 260 3 North Coast Route Backpacking Washington 1st Edition #1 South Coast Wilderness Trail - 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #2 Olympic Coast South: The Wildcatter Coast 17.5 1900 3 Toleak Point Backpacking Washington 1st Edition #2 Ozette Triangle 9.4 400 2 Cape Alava Loop (Ozette Triangle) 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #3. Shi Shi Beach and Point of the Shi Shi Beach 8.8 200 2 Arches 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #4. Olympic Peninsula Inland 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #6 Enchanted Valley 26.5 1800 3 Enchanted Valley Backpacking Washington #3 Spend at least one night in the Seven 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #8 Seven Lakes Basin 20 4000 3 Lakes Basin area. High Divide Loop Backpacking Washington #4 100 Classic Hikes in Washington 2nd Edition #98 Upper Lena Lake 14 3900 2 Upper Lena Lake Backpacking Washington #11 Hoh River to Glacier Meadows Walk the Hoh River Trail and camp at 34 4500 4 Glacier Meadows. -

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Wilderness Camping & Campfire Restrictions

0 R D E R GOAT ROCKS WILDERNESS, WILLIAM 0. DOUGLAS WILDERNESS, TRAPPER CREEK WILDERNESS, INDIAN HEAVEN WILDERNESS MT. ADAMS WILDERNESS, TATOOSH WILDERNESS, AND GLACIER VIEW WILDERNESS Gifford Pinchot and Wenatchee National Forests In order to protect the vegetation around lakes, streams, and meadows, to reduce soil compaction and erosion in heavily used areas and to enharice the Wilderness character and resource, the following acts, pursuant to 36 CFR 261.50 (a), are prohibited within Goat Rocks Wilderness, William 0. Douglas Wilderness, Trapper Creek Wilderness, Indian Heaven Wilderness, Mt. Adams Wilderness, Tatoosh Wilderness, and Glacier View Wilderness located within the Snoqualmie National Forest and the Gifford Pinchot National Forest and administered by the Wenatchee National Forest, until further notice. I Camping within 100 feet slope distance from the shoreline of any lake and/or the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail, EXCEPT at Dana Yelverton Shelter within Goat Rocks Wilderness, 36 CFR 261.58e. II Building, maintaining, or using a campfire, 36 CFR 261.52a. A. Within Goat Rocks Wilderness: within Shoe Lake Basin, at Dana Yelverton Shelter or within 1/4 mile of the shoreline of Goat Lake. B. Within Mt. Adams Wilderness: (1) Above the Round-The-Mountain Trail #9 from the Gifford Pinchot National Forest Boundary west to Pacific Crest Trail #2000 and (2) Above Pacific Crest Trail #2000 north to the intersection of Highline Trail #114 and (3) Above trail #114 north and east to the Gifford Pinchot Forest Boundary. C. Within Tatoosh Wilderness within Tatoosh Lakes Basin. D. Within William 0. Douglas Wilderness within 1/4 mile of the shoreline of Dewey Lakes. -

Page 1464 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1132

§ 1132 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1464 Department and agency having jurisdiction of, and reports submitted to Congress regard- thereover immediately before its inclusion in ing pending additions, eliminations, or modi- the National Wilderness Preservation System fications. Maps, legal descriptions, and regula- unless otherwise provided by Act of Congress. tions pertaining to wilderness areas within No appropriation shall be available for the pay- their respective jurisdictions also shall be ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- available to the public in the offices of re- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation gional foresters, national forest supervisors, System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- priations be available for additional personnel and forest rangers. stated as being required solely for the purpose of managing or administering areas solely because (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classi- they are included within the National Wilder- fications as primitive areas; Presidential rec- ness Preservation System. ommendations to Congress; approval of Con- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined gress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Ea- A wilderness, in contrast with those areas gles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado where man and his own works dominate the The Secretary of Agriculture shall, within ten landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where years after September 3, 1964, review, as to its the earth and its community of life are un- suitability or nonsuitability for preservation as trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- wilderness, each area in the national forests tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness classified on September 3, 1964 by the Secretary is further defined to mean in this chapter an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its of Agriculture or the Chief of the Forest Service primeval character and influence, without per- as ‘‘primitive’’ and report his findings to the manent improvements or human habitation, President. -

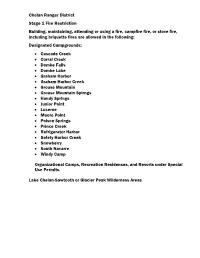

Chelan Ranger District Stage 1 Fire Restriction Building, Maintaining

Chelan Ranger District Stage 1 Fire Restriction Building, maintaining, attending or using a fire, campfire fire, or stove fire, including briquette fires are allowed in the following: Designated Campgrounds: • Cascade Creek • Corral Creek • Domke Falls • Domke Lake • Graham Harbor • Graham Harbor Creek • Grouse Mountain • Grouse Mountain Spirngs • Handy Springs • Junior Point • Lucerne • Moore Point • Poison Springs • Prince Creek • Refrigerator Harbor • Safety Harbor Creek • Snowberry • South Navarre • Windy Camp Organizational Camps, Recreation Residences, and Resorts under Special Use Permits. Lake Chelan-Sawtooth or Glacier Peak Wilderness Areas Cle Elum Ranger District Stage 1 Fire Restriction Building, maintaining, attending or using a fire, campfire fire, or stove fire, including briquette fires are allowed in the following: Designated Campgrounds: • Beverly • Cayuse • Cle Elum River • De Roux Creek Trailhead • East Kachess Group Site • Fish Lake • Icewater • Kachess • Manastash • Mineral Springs • Owhi • Red Mountain • Rider’s Camp • Salmon La Sac • Swauk • Taneum • Taneum Guard Station Cabin • Teanaway Guard Station Cabin • Ken Wilcox (Haney Meadow) • Wish Poosh Other Special Areas: Recreation Residences under permit from US Forest Service Camp Wahoo Outfitter Camp Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area, except areas specified below: Campfires are NOT permitted in the following areas: Above 5000 feet elevation on the Wenatchee National Forest. Within ½ mile of the following locations: Deep Lake Glacier Lake Lake Ivanhoe Rachel Lake Rebecca -

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L. 88–363, § 10, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) Sec. 1132. Extent of System. § 1110. Liability 1133. Use of wilderness areas. 1134. State and private lands within wilderness (a) United States areas. The United States Government shall not be 1135. Gifts, bequests, and contributions. liable for any act or omission of the Commission 1136. Annual reports to Congress. or of any person employed by, or assigned or de- § 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System tailed to, the Commission. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of (b) Payment; exemption of property from attach- policy; wilderness areas; administration for ment, execution, etc. public use and enjoyment, protection, preser- Any liability of the Commission shall be met vation, and gathering and dissemination of from funds of the Commission to the extent that information; provisions for designation as it is not covered by insurance, or otherwise. wilderness areas Property belonging to the Commission shall be In order to assure that an increasing popu- exempt from attachment, execution, or other lation, accompanied by expanding settlement process for satisfaction of claims, debts, or judg- and growing mechanization, does not occupy ments. and modify all areas within the United States (c) Individual members of Commission and its possessions, leaving no lands designated No liability of the Commission shall be im- for preservation and protection in their natural puted to any member of the Commission solely condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy on the basis that he occupies the position of of the Congress to secure for the American peo- member of the Commission.