Testing the Application of the EU Taxonomy to Core Banking Products: High Level Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

FI.News June 2019 In this issue: Island stopping: The importance of digital standards Supply chain finance: Making it more inclusive The Belt and Road Initiative: Bridging east and west Post-trade services: Delivering on new expectations Clearing the decks 10 Bridging east and west Making supply chain finance more inclusive 12 08 Contents Editorial welcome 03 Eye on the industry: Delivering on new 14 expectations in post-trade Big Interview: Island stopping 05 Regional spotlight: Are trade opportunities 16 in Africa shifting south? Innovation focus: Making supply chain 08 Regional focus: Seizing opportunities in 18 finance more inclusive central America Eye on the industry: Clearing the 10 News & awards 20 decks Expert view: Bridging east and west 12 Commerzbank in the press 22 2 Editorial welcome Never standing still Nikolaus Giesbert Divisional Board Member, Trade Finance & Cash Management While Commerzbank takes pride in its history, • Moving towards end-to-end, front-to-back, we are not a bank content to stand still. Having digital solutions; financed trade since 1870, we are accustomed to change. And today, technology, regulation • Being at the forefront of exploring how and changing client preferences stand to emerging technologies can transform fundamentally alter transaction banking, the landscape for trade finance and cash bringing new services, business models and management, and; competition. It’s a dynamic we are embracing. • Recognising permanent changes in the banking So rather than take a short-sighted view and sector and understanding the possibilities. focus simply on the automation of processes, we have invested resources and energy into Of course, extensive transformation must be digital transformation. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE R3’s distributed ledger initiative grows to 42 bank members and looks to extend reach to the broader financial services community Next phase of engagement to start in January and focus on non-bank institutions December 17, 2015 (New York/San Francisco/London) – Financial innovation company R3 has concluded its distributed ledger bank membership round with the addition of 12 new banks, bringing the total number to 42. Since its September launch, the company has seen a groundswell of interest in the consortium from financial services companies around the world. Having built a network that includes most of the world’s major global banks, and with the window for the admission of new bank members having closed under the consortium’s formative agreement, R3 will now focus efforts on broader engagement with a diverse range of institutions outside of the banking industry. As part of that initiative, R3 is considering options for participation in the consortium by various categories of non-bank institutions after the first of the year. David Rutter, CEO of R3 comments: “Partnering with a broad range of institutions has always been central to our strategy of developing distributed ledger technologies that will truly benefit the financial services industry as a whole. Securing the backing of 42 of the world’s leading banks demonstrates the level of interest in our initiative, and we now look forward to exploring collaboration with non-bank institutions and expanding our already diverse group.” BMO Financial Group, Danske Bank, Intesa Sanpaolo, Natixis, Nomura, Northern Trust, OP Financial Group, Banco Santander, Scotiabank, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, U.S. -

Responsible Banking 22 September 2019

Official Signing and Global Launch of the Principles for Responsible Banking 22 September 2019 Date/Time: 22 September, 14.00-15.30 Location: Trusteeship Council Attendance: About 300-400 high-level representatives from: banks becoming the Founding Signatories of the Principles for Responsible Banking, financial sector institutions, civil society, high-level UN representatives, VIPs, policy makers and international media. Background on the Event and the Principles for Responsible Banking: Official Signing and Global Launch of the Principles for Responsible Banking More than 40 bank CEOs from all five continents have personally committed to come to New York on 22nd and September 2019, to join United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Executive Director Inger Andersen to launch the UN Principles for Responsible Banking. The Principles will open the door to leverage the power of the US$ 134.1 trillion banking industry, which is responsible for more than two-thirds of all financing globally, and 90% of financing in developing countries – making their engagement critical to achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Already endorsed by 130 banks from over 45 countries representing more than US$47 trillion in assets and with that over one third of the global banking industry, the Principles are the most significant mechanism ever created jointly between the UN and the global banking industry. Background The Principles for Responsible Banking set the criteria for responsible and sustainable banking. The 130 banks that have already committed to the Principles, and the many others that are set to follow, demonstrate the highest-level commitment from the banking industry. -

Over 100 Global Financial Institutions Are Exiting Coal, with More to Come Every Two Weeks a Bank, Insurer Or Lender Announces New Restrictions on Coal

Tim Buckley 1 Director of Energy Finance Studies, Australasia 27 February 2019 Over 100 Global Financial Institutions Are Exiting Coal, With More to Come Every Two Weeks a Bank, Insurer or Lender Announces New Restrictions on Coal Executive Summary Today, over 100 globally significant financial institutions have divested from thermal coal, including 40% of the top 40 global banks and 20 globally significant insurers. Momentum is building. Since January 2018, a bank or insurer announced their divestment from coal mining and/or coal-fired power plants Global capital is fleeing every month, and a financial institution the coal sector. who had previously announced a divestment/exclusion policy tightened This is no passing fad. up their policy to remove loopholes, every two weeks. In total, 34 coal divestment/restriction policy announcements have been made by globally significant financial institutions since the start of 2018. In the first nine weeks of 2019, there have been five new announcements of banks and insurers divesting from coal. Global capital is fleeing the thermal coal sector. This is no passing fad. Since 2013 more than 100 global financial institutions have made increasingly tight divestment/exclusion policies around thermal coal. When the World Bank Group moved to exit coal in 2013, the ball started rolling. Following, Axa and Allianz become the first global insurers to restrict coal insurance and investment respectively in 2015, and their policies have subsequently been materially enhanced. Next, some 35 export credit agencies (ECA) released a joint statement agreeing to new rules restricting coal power lending. In the same year, the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank trumpeted its global green credentials with the Chairman confirming the Bank was in practice ruling out finance for coal-fired power plants. -

List of Our Main Reimbursing Banks for Receipt of Cover for Commercial Transactions

1 (2) © OP June 2018 LIST OF OUR MAIN REIMBURSING BANKS FOR RECEIPT OF COVER FOR COMMERCIAL TRANSACTIONS EURO ZONE OP Corporate Bank plc, Helsinki, OP Financial Group's central bank, acts as a direct clearing member of EBA (Euro Banking Association) and therefore receives all commercial payments in favour of OP Financial Group's customers through EBA. If you are not a clearing member in EBA you may use TARGET or one of the following correspondents: CURRENCY CODE SWIFT CORRESPONDENT BANK NAME COUNTRY EUR KREDBEBB KBC Bank N.V., Brussels Belgium EUR CITIGB2L Citibank N.a, London United Kingdom EUR DEUTDEFF Deutsche Bank Ag, Frankfurt am Main Germany OTHER CURRENCIES CURRENCY CODE SWIFT CORRESPONDENT BANK NAME COUNTRY AED ADCBAEAA Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank, Abu Dhabi UAE AUD NATAAU3303M National Australia Bank Ltd, Melbourne Australia BGN RZBBBGSF Raiffeisenbank (Bulgaria) EAD, Sofia Bulgaria CAD ROYCCAT2 Royal Bank of Canada, Toronto Canada CHF UBSWCHZH80A UBS Switzerland AG, Zürich Switzerland CNH BKCHHKHH Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited, Hong Kong China CNH HSBCHKHHHKH Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corp. Ltd, Hong Kong China CNY BKCHCNBJS00 Bank of China, Shanghai China CNY HSBCCNSH HSBC Bank (China) Company Limited, Shanghai China CZK CEKOCZPP Ceskoslovenska Obchodni Banka A.S., Prague Czech Republic DKK JYBADKKK Jyske Bank A/S, Copenhagen Denmark DKK DABADKKK Danske Bank A/S, Copenhagen Denmark GBP RBOSGB2L The Royal Bank of Scotland Plc, London United Kingdom GBP LOYDGB2L Lloyds Bank Plc, London United Kingdom HKD HASEHKHH Hang -

Accelerating Open Banking

Accelerating open banking How the Nordics are driving new opportunities across industries. A white paper by Nordic API Gateway May 2020 Empowering frictionless financial futures for all The open banking platform Nordic API Gateway is the only API aggregator that offers full coverage of all business and personal bank accounts in the Nordics and soon the rest of Europe. With its in-depth market approach, Nordic API Gateway was founded to standardise the format of financial data and payments, enabling frictionless financial futures for all industries. Today, the technology behind Nordic API Gateway powers more than 50 companies including major banks, such as Danske Bank, Jyske Bank, OP Financial Group and DNB, as well as payment providers, accounting systems and SMBs, with access to real-time data and low-cost payment options. In early 2020, Nordic API Gateway commissioned a survey of more than 100 decision makers within the financial sector and payments industry, and accounting service providers across the Nordics – Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland – with the aim to assess the status of the Nordic region on its approach toward open banking. Interviews were monitored to ensure as balanced a spread as possible across country, sector, number of employees and turnover. An important message Because the survey was conducted before the Coronavirus found a foothold in Europe, this report does not take the extraordinary situation into consideration. Therefore, the data set does not account for any possible changes in priorities for the surveyed businesses and institutions that could have occured due to the COVID-19 crisis. Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................4 1 Open banking at a glance .....................................................................................6 2 Why the Nordics are the perfect fit for open banking .................. -

TERMS and CONDITIONS of the OFFERING “Subscription” Means Below an Offer Or Commitment Provided by an Investor in the Offeri

TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF THE OFFERING “Subscription” means below an offer or commitment provided by an investor in the Offering, whether the investor has offered or committed to purchase Sale Shares or to subscribe New Shares. Correspondingly, “subscriber”, “subscription period”, “subscription place”, “subscription price”, “subscription offer” and “subscription commitment” (and other corresponding terms) refer to both Share Issue and Share Sale. General Terms and Conditions of the Offering The Offering The offering comprises the Share Issue and Share Sale (as defined below) (together, the “Offering”). Through the Share Issue, Kojamo plc (together with its subsidiaries on a consolidated basis, the “Company”, “Kojamo” or the “Kojamo Group”, except where it is clear from the context that the term means Kojamo plc or a particular subsidiary or business unit only) aims to raise gross proceeds of approximately EUR 150 million by offering new shares in the Company (the “New Shares”) for subscription (the “Share Issue”). The number of New Shares to be issued will be determined based on the final price per Offer Share (as defined below) (the “Final Offer Price”). The Company will issue 16,222,184 New Shares assuming that (i) the Final Offer Price will be at the mid-point of the Preliminary Price Range (as defined below), (ii) a total of 60,000 New Shares would be subscribed for in the Personnel Offering (as defined below) at the discount applicable to such New Shares and (iii) the Company will raise gross proceeds of no more than EUR 150 million. -

Debt Investor Presentation FY/2019

Debt Investor Presentation FY/2019 OP Financial Group and issuing entities OP Corporate Bank plc and OP Mortgage Bank www.op.fi/debtinvestors P O © 2 Disclaimer Certain statements in this presentation are based on the beliefs of our management as well as assumptions made by and information currently available to the management. All forward-looking statements in this presentation expressing the management’s expectations, beliefs, estimates, forecasts, projections and assumptions are based on the current view of the future development in the operating environment and the future financial performance of OP Financial Group and its various functions. No assurance can be given that such expectations will prove to have been correct. Accordingly, results may differ materially from those set out in the forward-looking statements as a result of various factors. OP Financial Group has used sources of information which it considers to be reliable, and the accuracy and reliability of which it has sought to establish to the best of its ability, but it can nevertheless not guarantee their accuracy or reliability. A number of different factors may cause the actual performance to deviate significantly from the forward-looking statements in the presentations. Our financial reports also describe risks and factors that could affect our future performance and the industry in which we operate. Should one or more of these risks or uncertainties materialise or should any underlying assumptions prove to be incorrect, our actual financial position or results of operations could materially differ from that presented as anticipated, believed, estimated or expected. The views and other information provided are current as at the date of when such information was provided and may be subject to change without notice. -

OP Financial Group's H1 2020 Debt Investor Presentation

Debt Investor Presentation H1/2020 OP Financial Group and issuing entities OP Corporate Bank plc and OP Mortgage Bank www.op.fi/debtinvestors OP will publish the quarterly Capital Adequacy Report for 30 June 2020 on week 31. Slide 44 of this presentation will be updated afterwards. 2 Disclaimer Certain statements in this presentation are based on the beliefs of our management as well as assumptions made by and information currently available to the management. All forward-looking statements in this presentation expressing the management’s expectations, beliefs, estimates, forecasts, projections and assumptions are based on the current view of the future development in the operating environment and the future financial performance of OP Financial Group and its various functions. No assurance can be given that such expectations will prove to have been correct. Accordingly, results may differ materially from those set out in the forward-looking statements as a result of various factors. OP Financial Group has used sources of information which it considers to be reliable, and the accuracy and reliability of which it has sought to establish to the best of its ability, but it can nevertheless not guarantee their accuracy or reliability. A number of different factors may cause the actual performance to deviate significantly from the forward-looking statements in the presentations. Our financial reports also describe risks and factors that could affect our future performance and the industry in which we operate. Should one or more of these risks or uncertainties materialise or should any underlying assumptions prove to be incorrect, our actual financial position or results of operations could materially differ from that presented as anticipated, believed, estimated or expected. -

July 2021 Nordic Banks Join Forces to Recover Lost Ground in E- Commerce, a Credit Positive

FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS ISSUER COMMENT Vipps 5 July 2021 Nordic banks join forces to recover lost ground in e- commerce, a credit positive On 30 June, a number of large Nordic banks announced that they were merging their mobile payment providers – Vipps in Norway, MobilePay in Denmark and Pivo in Finland – to create Contacts a mobile payment provider with parent company Vipps AS that offers a single technical solution across the Nordics. The merger aims to improve the attractiveness of the service Niclas Boheman +46.8.5179.1281 VP-Senior Analyst to pan-Nordic e-commerce retailers, share development costs and boost the potential for [email protected] adding new payment products, a credit positive for the owner banks. The owner banks are 1 Simon James Robin +44 207 772 5347 Denmark's Danske Bank A/S (A2 negative/A3 stable, baa2 ), Norway's DNB Bank ASA (Aa2/ Ainsworth Aa2 stable, a3), a majority of smaller Norwegian banks and Finland's OP Financial Group Associate Managing Director (OP), which includes the rated entity OP Corporate Bank (Aa3/Aa3 stable, a3). [email protected] The new merged company will serve 11 million users and more than 330,000 shops and CLIENT SERVICES web retailers across the Nordic region. Given the high penetration these mobile payment Americas 1-212-553-1653 providers have domestically, the merger brings scale to deliver further growth focused on Asia Pacific 852-3551-3077 growing the merged company's presence in e-commerce. Building new partnerships is essential to stay relevant in an increasingly digitalised environment, with a low and declining Japan 81-3-5408-4100 share of physical notes and coins in transactions. -

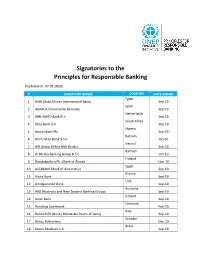

Signatories to the Principles for Responsible Banking

Signatories to the Principles for Responsible Banking (Updated on: 07.09.2020) # SIGNATORY BANKS COUNTRY DATE SIGNED Egypt 1 AAIB (Arab African International Bank) Sep-19 Spain 2 ABANCA Corporación Bancaria Sep-19 Netherlands 3 ABN AMRO Bank N.V. Sep-19 South Africa 4 Absa Bank Ltd. Sep-19 Nigeria 5 Access Bank Plc Sep-19 Bahrain 6 Ahli United Bank B.S.C Jan-20 Ireland 7 AIB Group (Allied Irish Banks) Sep-19 Bahrain 8 Al Baraka Banking Group B.S.C. Oct-19 Finland 9 Ålandsbanken Plc. (Bank of Åland) Nov-19 Egypt 10 ALEXBANK (Bank of Alexandria) Sep-19 Greece 11 Alpha Bank Sep-19 USA 12 Amalgamated Bank Sep-19 Australia 13 ANZ (Australia and New Zealand Banking Group) Sep-19 Iceland 14 Arion Bank Sep-19 Denmark 15 Aurskorg Sparebank Feb-20 Italy 16 Banca MPS (Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena) Sep-19 Ecuador 17 Banco Bolivariano Dec-19 Brazil 18 Banco Bradesco S.A. Sep-19 Brazil 19 Banco da Amazônia Jan-20 Argentina 20 Banco de Galicia y Buenos Aires SA Sep-19 Ecuador 21 Banco de la Produccion S.A Produbanco Sep-19 Ecuador 22 Banco de Machala S.A. Sep-19 Mexico 23 Banco del Bajio, S.A. Aug-20 Ecuador 24 Banco Diners Club del Ecuador S.A. Nov-19 Nicaragua 25 Banco Grupo Promerica Nicaragua Sep-19 Ecuador 26 Banco Guayaquil Sep-19 El Salvador 27 Banco Hipotecario de El Salvador S.A. Sep-19 Ecuador 28 Banco Pichincha Sep-19 Dominican Republic 29 Banco Popular Dominicano Sep-19 Costa Rica 30 Banco Promerica Costa Rica Sep-19 Paraguay 31 Banco Regional Jul-20 Spain 32 Banco Sabadell Sep-19 Ecuador 33 Banco Solidario Nov-19 Colombia 34 Bancolombia -

Nber Working Paper Series Bail-Ins and Bail-Outs

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BAIL-INS AND BAIL-OUTS: INCENTIVES, CONNECTIVITY, AND SYSTEMIC STABILITY Benjamin Bernard Agostino Capponi Joseph E. Stiglitz Working Paper 23747 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23747 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2017 We are grateful to George Pennacchi (discussant), Yiming Ma (discussant), Asuman Ozdaglar, Alireza Tahbaz-Salehi, Darrell Duffie, Jaksa Cvitaniec, Matt Elliott, Douglas Gale, Matthew Jackson, Piero Gottardi, and Felix Corell for interesting discussions and perceptive comments. We would also like to thank the seminar participants of the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Cambridge Finance Seminar series, the London School of Economics, Stanford University, New York University, the Fields Institute, the third annual conference on Network Science and Economics, the Columbia Conference on Financial Networks: Big Risks, Macroeconomic Externalities, and Policy Commitment Devices, the 2018 SFS Cavalcade North America, and the 2018 North American Summer Meeting of the Econometric society for their valuable feedback. The research of Agostino Capponi is supported by a NSF-CMMI: 1752326 CAREER grant. Benjamin Bernard acknowledges financial support from grant P2SKP1 171737 by the Swiss National Science Foundation. Joseph Stiglitz acknowledges the support of the Columbia Business School and of the grant on Financial Stability from the Institute for New Economic Thinking. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications.