Altered Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty Years of Berkeley Unix : from AT&T-Owned to Freely

Twenty Years of Berkeley Unix : From AT&T-Owned to Freely Redistributable Marshall Kirk McKusick Early History Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie presented the first Unix paper at the Symposium on Operating Systems Principles at Purdue University in November 1973. Professor Bob Fabry, of the University of California at Berkeley, was in attendance and immediately became interested in obtaining a copy of the system to experiment with at Berkeley. At the time, Berkeley had only large mainframe computer systems doing batch processing, so the first order of business was to get a PDP-11/45 suitable for running with the then-current Version 4 of Unix. The Computer Science Department at Berkeley, together with the Mathematics Department and the Statistics Department, were able to jointly purchase a PDP-11/45. In January 1974, a Version 4 tape was delivered and Unix was installed by graduate student Keith Standiford. Although Ken Thompson at Purdue was not involved in the installation at Berkeley as he had been for most systems up to that time, his expertise was soon needed to determine the cause of several strange system crashes. Because Berkeley had only a 300-baud acoustic-coupled modem without auto answer capability, Thompson would call Standiford in the machine room and have him insert the phone into the modem; in this way Thompson was able to remotely debug crash dumps from New Jersey. Many of the crashes were caused by the disk controller's inability to reliably do overlapped seeks, contrary to the documentation. Berkeley's 11/45 was among the first systems that Thompson had encountered that had two disks on the same controller! Thompson's remote debugging was the first example of the cooperation that sprang up between Berkeley and Bell Labs. -

SIGOPS Annual Report 2012

SIGOPS Annual Report 2012 Fiscal Year July 2012-June 2013 Submitted by Jeanna Matthews, SIGOPS Chair Overview SIGOPS is a vibrant community of people with interests in “operatinG systems” in the broadest sense, includinG topics such as distributed computing, storaGe systems, security, concurrency, middleware, mobility, virtualization, networkinG, cloud computinG, datacenter software, and Internet services. We sponsor a number of top conferences, provide travel Grants to students, present yearly awards, disseminate information to members electronically, and collaborate with other SIGs on important programs for computing professionals. Officers It was the second year for officers: Jeanna Matthews (Clarkson University) as Chair, GeorGe Candea (EPFL) as Vice Chair, Dilma da Silva (Qualcomm) as Treasurer and Muli Ben-Yehuda (Technion) as Information Director. As has been typical, elected officers agreed to continue for a second and final two- year term beginning July 2013. Shan Lu (University of Wisconsin) will replace Muli Ben-Yehuda as Information Director as of AuGust 2013. Awards We have an excitinG new award to announce – the SIGOPS Dennis M. Ritchie Doctoral Dissertation Award. SIGOPS has lonG been lackinG a doctoral dissertation award, such as those offered by SIGCOMM, Eurosys, SIGPLAN, and SIGMOD. This new award fills this Gap and also honors the contributions to computer science that Dennis Ritchie made durinG his life. With this award, ACM SIGOPS will encouraGe the creativity that Ritchie embodied and provide a reminder of Ritchie's leGacy and what a difference a person can make in the field of software systems research. The award is funded by AT&T Research and Alcatel-Lucent Bell Labs, companies that both have a strong connection to AT&T Bell Laboratories where Dennis Ritchie did his seminal work. -

July 1St Century and a Half Later by 1960S

The underlying technology, the After CTSS, he moved onto Leibniz wheel, was reused a Multics [Nov 30] during the mid- July 1st century and a half later by 1960s. That OS is often deemed Thomas de Colmar [May 5] in his a commercial failure, but arithmometer, the first mass- nevertheless had an enormous Gottfried Wilhelm produced mechanical calculator. influence on the design of later systems. For example, UNIX was In 1961, Norbert Wiener [Nov written by two ex-Multics (von) Leibni[t]z 26] suggested that Leibniz programmers, Ken Thompson should be considered the patron Born: July 1, 1646; [Feb 4] and Dennis Ritchie [Sept saint of cybernetics. Leipzig, Saxony 9]. Died: Nov. 14, 1716 Corbató is credited with the first During the 1670s, Leibniz use of passwords (to secure independently developed a very Hans Peter Luhn access to CTSS), although he similar theory of calculus to that Born: July 1, 1896; himself suggested that they first of Issac Newton. More appeared in IBM’s SABRE Barmen, Germany importantly for us, at around the ticketing system [Nov 5]. same time, in 1672, Leibniz cam Died: August 19, 1964 Corbató’s Law: The number of up with the first practical Luhn is sometimes called “the lines of code a programmer can calculating machine, which he father of information retrieval”, write in a fixed period of time is called the “Step Reckoner”. He due to his invention of the Luhn the same independent of the had the initial idea from algorithm, KWIC (Key Words In language used. examining a pedometer. Context) indexing, and Selective It was the first calculator that Dissemination of Information could perform all four arithmetic (“SDI”) operations, although the carry The Luhn algorithm is a Project MAC operation wasn't fully checksum formula used to July 1, 1963 mechanized. -

Introduction

Introduction J. M. P. Alves Laboratory of Genomics & Bioinformatics in Parasitology Department of Parasitology, ICB, USP BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 ● Introduction to computers and computing (UNIX) ● Linux basics ● Introduction to the Bash shell ● Connecting to this course’s virtual machine J.M.P. Alves 2 / 82 BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 TuxThe Linux mascot “TUXedo”... By Larry Ewing, 1996 ...or Torvalds UniX Tux's ancestor J.M.P. Alves 3 / 82 BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 Linux (Unix) & science Why so popular together? ● Historical reasons (programs made for Unix/Linux) ● Available on any kind of computer, especially powerful servers ● Works efficiently with humongous text files (head, tail, sort, cut, paste, grep, etc.) ● Complicated tasks can be made easy by concatenating simpler commands (piping) ● Creating new programs is easy – tools just one or two commands (or clicks) away (gcc, g++, python, perl) ● Stable, efficient, open (free software), no cost (software for free) J.M.P. Alves 4 / 82 BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 What IS this Linux, anyway? J.M.P. Alves 5 / 82 BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 Operating system J.M.P. Alves 6 / 82 BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 An operating system is a collection of programs that initialize the computer's hardware, providing basic instructions for the control of devices, managing and scheduling tasks, and regulating their interactions with each other. J.M.P. Alves 7 / 82 BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 You WhatsApp Android Phone J.M.P. Alves 8 / 82 BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 You MUSCLE Linux Computer J.M.P. Alves 9 / 82 BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 formerly: J.M.P. Alves 10 / 82 BMP0260 / ICB5765 / IBI5765 History J.M.P. -

Mount Litera Zee School Grade-VIII G.K Computer and Technology Read and Write in Notebook: 1

Mount Litera Zee School Grade-VIII G.K Computer and Technology Read and write in notebook: 1. Who is called as ‘Father of Computer’? a. Charles Babbage b. Bill Gates c. Blaise Pascal d. Mark Zuckerberg 2. Full Form of virus is? a. Visual Information Resource Under Seize b. Virtual Information Resource Under Size c. Vital Information Resource Under Seize d. Virtue Information Resource Under Seize 3. How many MB (Mega Byte) makes one GB (Giga Byte)? a. 1025 MB b. 1030 MB c. 1020 MB d. 1024 MB 4. Internet was developed in _______. a. 1973 b. 1993 c. 1983 d. 1963 5. Which was the first virus detected on ARPANET, the forerunner of the internet in the early 1970s? a. Exe Flie b. Creeper Virus c. Peeper Virus d. Trozen horse 6. Who is known as the Human Computer of India? a. Shakunthala Devi b. Nandan Nilekani c. Ajith Balakrishnan d. Manish Agarwal 7. When was the first smart phone launched? a. 1992 b. 1990 c. 1998 d. 2000 8. Which one of the following was the first search engine used? a. Google b. Archie c. AltaVista d. WAIS 9. Who is known as father of Internet? a. Alan Perlis b. Jean E. Sammet c. Vint Cerf d. Steve Lawrence 10. What us full form of GOOGLE? a. Global Orient of Oriented Group Language of Earth b. Global Organization of Oriented Group Language of Earth c. Global Orient of Oriented Group Language of Earth d. Global Oriented of Organization Group Language of Earth 11. Who developed Java Programming Language? a. -

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

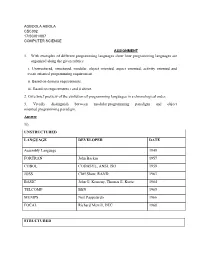

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

The UNIX Time- Sharing System

1. Introduction There have been three versions of UNIX. The earliest version (circa 1969–70) ran on the Digital Equipment Cor- poration PDP-7 and -9 computers. The second version ran on the unprotected PDP-11/20 computer. This paper describes only the PDP-11/40 and /45 [l] system since it is The UNIX Time- more modern and many of the differences between it and older UNIX systems result from redesign of features found Sharing System to be deficient or lacking. Since PDP-11 UNIX became operational in February Dennis M. Ritchie and Ken Thompson 1971, about 40 installations have been put into service; they Bell Laboratories are generally smaller than the system described here. Most of them are engaged in applications such as the preparation and formatting of patent applications and other textual material, the collection and processing of trouble data from various switching machines within the Bell System, and recording and checking telephone service orders. Our own installation is used mainly for research in operating sys- tems, languages, computer networks, and other topics in computer science, and also for document preparation. UNIX is a general-purpose, multi-user, interactive Perhaps the most important achievement of UNIX is to operating system for the Digital Equipment Corpora- demonstrate that a powerful operating system for interac- tion PDP-11/40 and 11/45 computers. It offers a number tive use need not be expensive either in equipment or in of features seldom found even in larger operating sys- human effort: UNIX can run on hardware costing as little as tems, including: (1) a hierarchical file system incorpo- $40,000, and less than two man years were spent on the rating demountable volumes; (2) compatible file, device, main system software. -

![Arxiv:2106.11534V1 [Cs.DL] 22 Jun 2021 2 Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, China 3 University of Southampton, Southampton, U.K](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7768/arxiv-2106-11534v1-cs-dl-22-jun-2021-2-nanjing-university-of-science-and-technology-nanjing-china-3-university-of-southampton-southampton-u-k-1557768.webp)

Arxiv:2106.11534V1 [Cs.DL] 22 Jun 2021 2 Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, China 3 University of Southampton, Southampton, U.K

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Turing Award elites revisited: patterns of productivity, collaboration, authorship and impact Yinyu Jin1 · Sha Yuan1∗ · Zhou Shao2, 4 · Wendy Hall3 · Jie Tang4 Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract The Turing Award is recognized as the most influential and presti- gious award in the field of computer science(CS). With the rise of the science of science (SciSci), a large amount of bibliographic data has been analyzed in an attempt to understand the hidden mechanism of scientific evolution. These include the analysis of the Nobel Prize, including physics, chemistry, medicine, etc. In this article, we extract and analyze the data of 72 Turing Award lau- reates from the complete bibliographic data, fill the gap in the lack of Turing Award analysis, and discover the development characteristics of computer sci- ence as an independent discipline. First, we show most Turing Award laureates have long-term and high-quality educational backgrounds, and more than 61% of them have a degree in mathematics, which indicates that mathematics has played a significant role in the development of computer science. Secondly, the data shows that not all scholars have high productivity and high h-index; that is, the number of publications and h-index is not the leading indicator for evaluating the Turing Award. Third, the average age of awardees has increased from 40 to around 70 in recent years. This may be because new breakthroughs take longer, and some new technologies need time to prove their influence. Besides, we have also found that in the past ten years, international collabo- ration has experienced explosive growth, showing a new paradigm in the form of collaboration. -

Turing Award • John Von Neumann Medal • NAE, NAS, AAAS Fellow

15-712: Advanced Operating Systems & Distributed Systems A Few Classics Prof. Phillip Gibbons Spring 2021, Lecture 2 Today’s Reminders / Announcements • Summaries are to be submitted via Canvas by class time • Announcements and Q&A are via Piazza (please enroll) • Office Hours: – Prof. Phil Gibbons: Fri 1-2 pm & by appointment – TA Jack Kosaian: Mon 1-2 pm – Zoom links: See canvas/Zoom 2 CS is a Fast Moving Field: Why Read/Discuss Old Papers? “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” - George Santayana, The Life of Reason, Volume 1, 1905 See what breakthrough research ideas look like when first presented 3 The Rise of Worse is Better Richard Gabriel 1991 • MIT/Stanford style of design: “the right thing” – Simplicity in interface 1st, implementation 2nd – Correctness in all observable aspects required – Consistency – Completeness: cover as many important situations as is practical • Unix/C style: “worse is better” – Simplicity in implementation 1st, interface 2nd – Correctness, but simplicity trumps correctness – Consistency is nice to have – Completeness is lowest priority 4 Worse-is-better is Better for SW • Worse-is-better has better survival characteristics than the-right-thing • Unix and C are the ultimate computer viruses – Simple structures, easy to port, required few machine resources to run, provide 50-80% of what you want – Programmer conditioned to sacrifice some safety, convenience, and hassle to get good performance and modest resource use – First gain acceptance, condition users to expect less, later -

Corbató Transcript Final

A. M. Turing Award Oral History Interview with Fernando J. (“Corby”) Corbató by Steve Webber Plum Island, Massachusetts April 6, 2018 Webber: Hi. My name is Steve Webber. It’s April 6th, 2018. I’m here to interview Fernando Corbató – everyone knows him as “Corby” – the ACM Turing Award winner of 1990 for his contributions to computer science. So Corby, tell me about your early life, where you went to school, where you were born, your family, your parents, anything that’s interesting for the history of computer science. Corbató: Well, my parents met at University of California, Berkeley, and they… My father got his doctorate in Spanish literature – and I was born in Oakland, California – and proceeded to… he got his first position at UCLA, which was then a new campus in Los Angeles, as a professor of Spanish literature. So I of course wasn’t very conscious of much at those ages, but I basically grew up in West Los Angeles and went to public high schools, first grammar school, then junior high, and then I began high school. Webber: What were your favorite subjects in high school? I tended to enjoy the mathematics type of subjects. As I recall, algebra was easy and enjoyable. And the… one of the results of that was that I was in high school at the time when World War II… when Pearl Harbor occurred and MIT was… rather the United States was drawn into the war. As I recall, Pearl Harbor occurred… I think it was on a Sunday, but one of the results was that it shocked the US into reacting to the war effort, and one of the results was that everything went into kind of a wartime footing. -

Alan Mathison Turing and the Turing Award Winners

Alan Turing and the Turing Award Winners A Short Journey Through the History of Computer TítuloScience do capítulo Luis Lamb, 22 June 2012 Slides by Luis C. Lamb Alan Mathison Turing A.M. Turing, 1951 Turing by Stephen Kettle, 2007 by Slides by Luis C. Lamb Assumptions • I assume knowlege of Computing as a Science. • I shall not talk about computing before Turing: Leibniz, Babbage, Boole, Gödel... • I shall not detail theorems or algorithms. • I shall apologize for omissions at the end of this presentation. • Comprehensive information about Turing can be found at http://www.mathcomp.leeds.ac.uk/turing2012/ • The full version of this talk is available upon request. Slides by Luis C. Lamb Alan Mathison Turing § Born 23 June 1912: 2 Warrington Crescent, Maida Vale, London W9 Google maps Slides by Luis C. Lamb Alan Mathison Turing: short biography • 1922: Attends Hazlehurst Preparatory School • ’26: Sherborne School Dorset • ’31: King’s College Cambridge, Maths (graduates in ‘34). • ’35: Elected to Fellowship of King’s College Cambridge • ’36: Publishes “On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheindungsproblem”, Journal of the London Math. Soc. • ’38: PhD Princeton (viva on 21 June) : “Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals”, supervised by Alonzo Church. • Letter to Philipp Hall: “I hope Hitler will not have invaded England before I come back.” • ’39 Joins Bletchley Park: designs the “Bombe”. • ’40: First Bombes are fully operational • ’41: Breaks the German Naval Enigma. • ’42-44: Several contibutions to war effort on codebreaking; secure speech devices; computing. • ’45: Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) Computer. Slides by Luis C. -

Linux Internals

LINUX INTERNALS Peter Chubb and Etienne Le Sueur [email protected] A LITTLE BIT OF HISTORY • Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie in 1967–70 • USG and BSD • John Lions 1976–95 • Andrew Tanenbaum 1987 • Linux Torvalds 1991 NICTA Copyright c 2011 From Imagination to Impact 2 The history of UNIX-like operating systems is a history of people being dissatisfied with what they have and wanting to do some- thing better. It started when Ken Thompson got bored with MUL- TICS and wanted to write a computer game (Space Travel). He found a disused PDP-7, and wrote an interactive operating sys- tem to run his game. The main contribution at this point was the simple file-system abstraction. (Ritchie 1984) Other people found it interesting enough to want to port it to other systems, which led to the first major rewrite — from assembly to C. In some ways UNIX was the first successfully portable OS. After Ritchie & Thompson (1974) was published, AT&T became aware of a growing market for UNIX. They wanted to discourage it: it was common for AT&T salesmen to say, ‘Here’s what you get: A whole lot of tapes, and an invoice for $10 000’. Fortunately educational licences were (almost) free, and universities around the world took up UNIX as the basis for teaching and research. The University of California at Berkeley was one of those univer- NICTA Copyright c 2011 From Imagination to Impact 2-1 sities. In 1977, Bill Joy (a postgrad) put together and released the first Berkeley Software Distribution — in this instance, the main additions were a pascal compiler and Bill Joy’s ex editor.